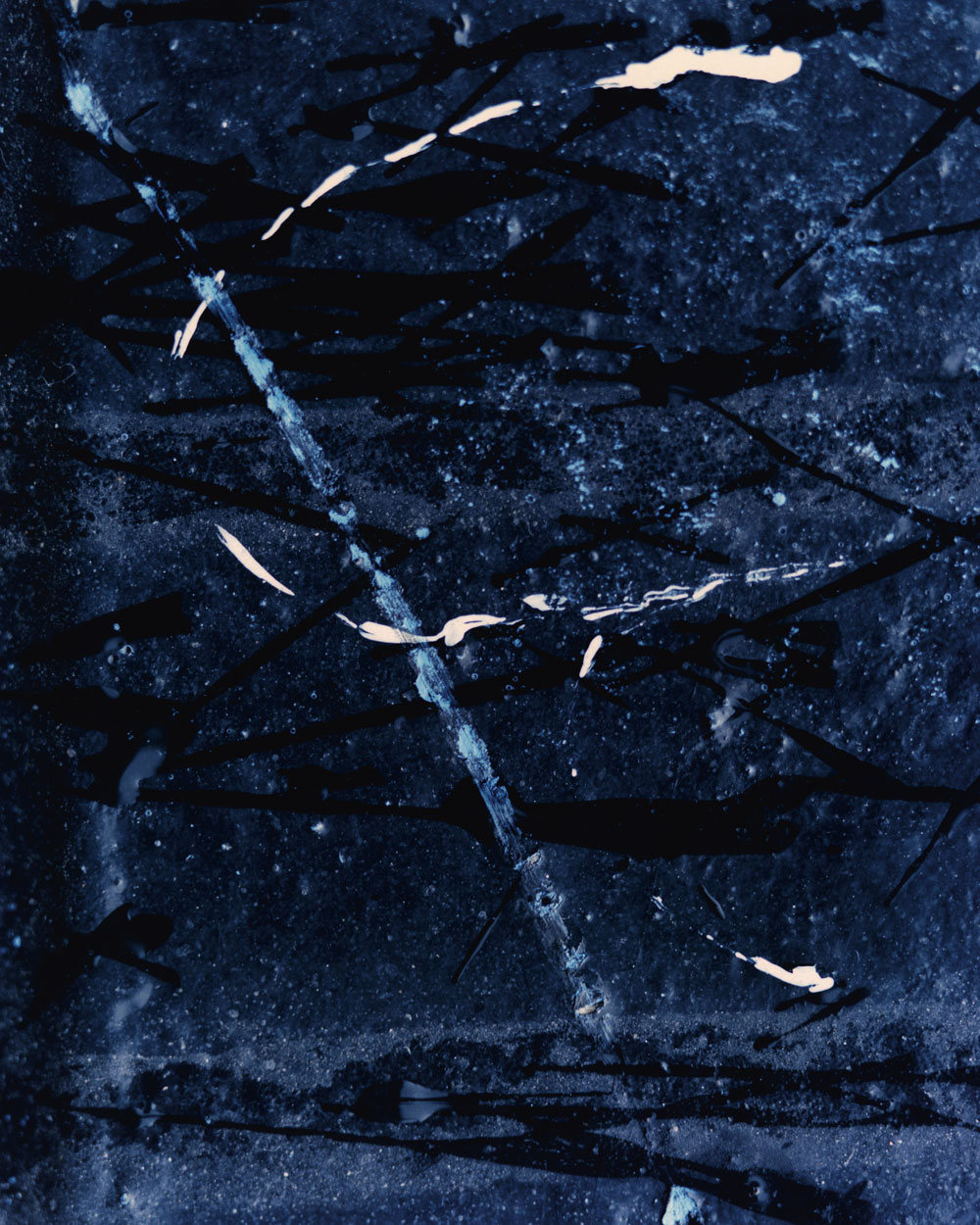

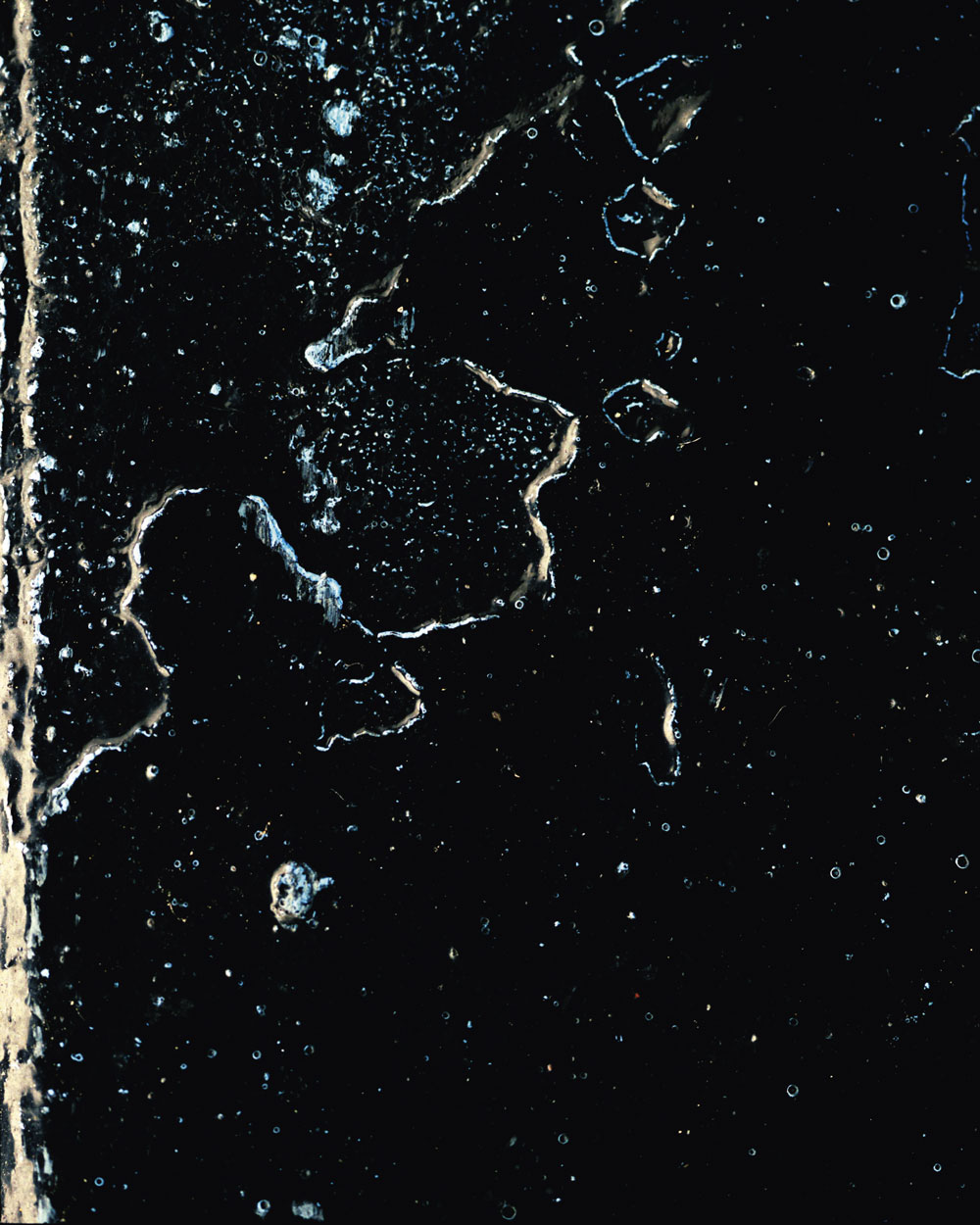

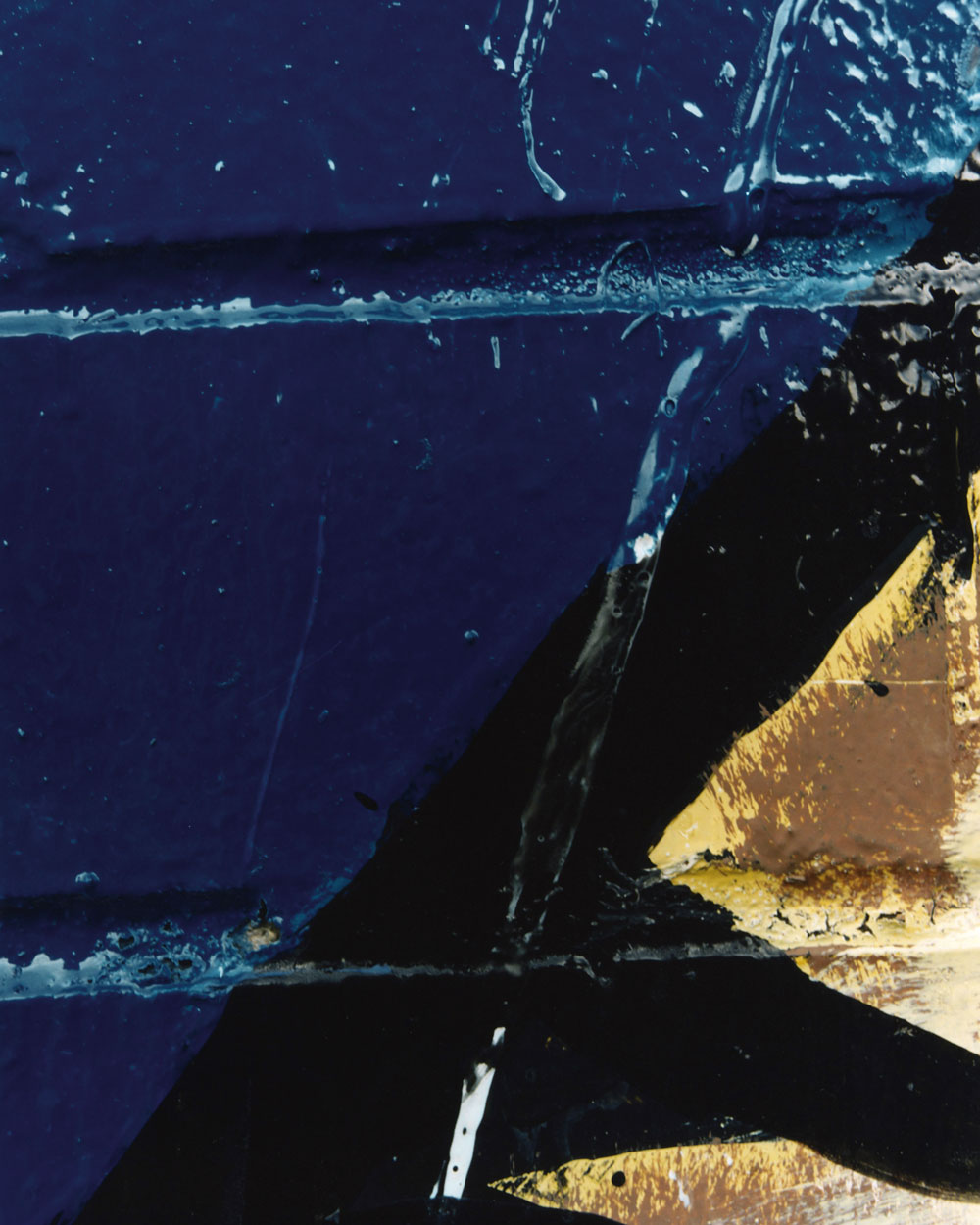

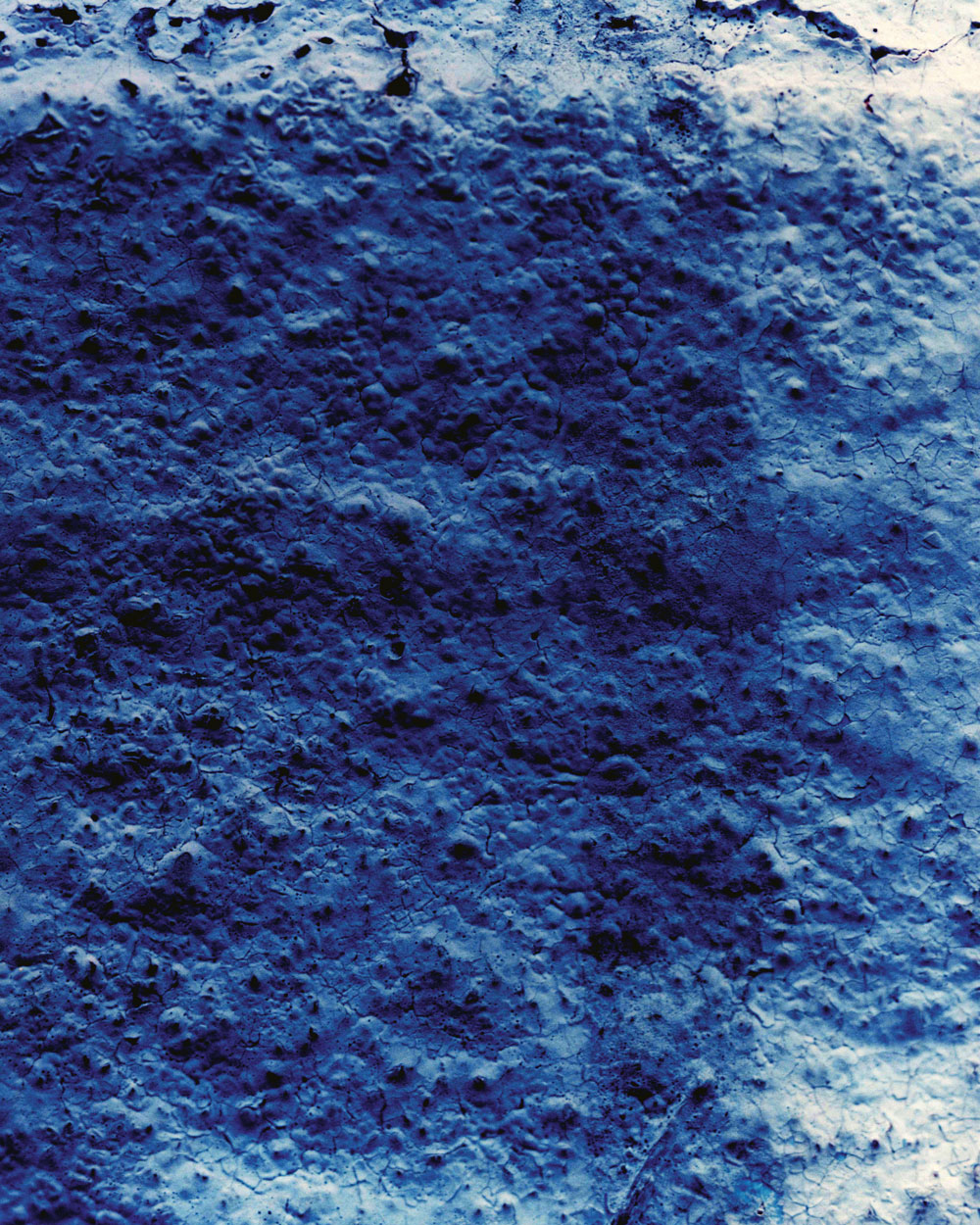

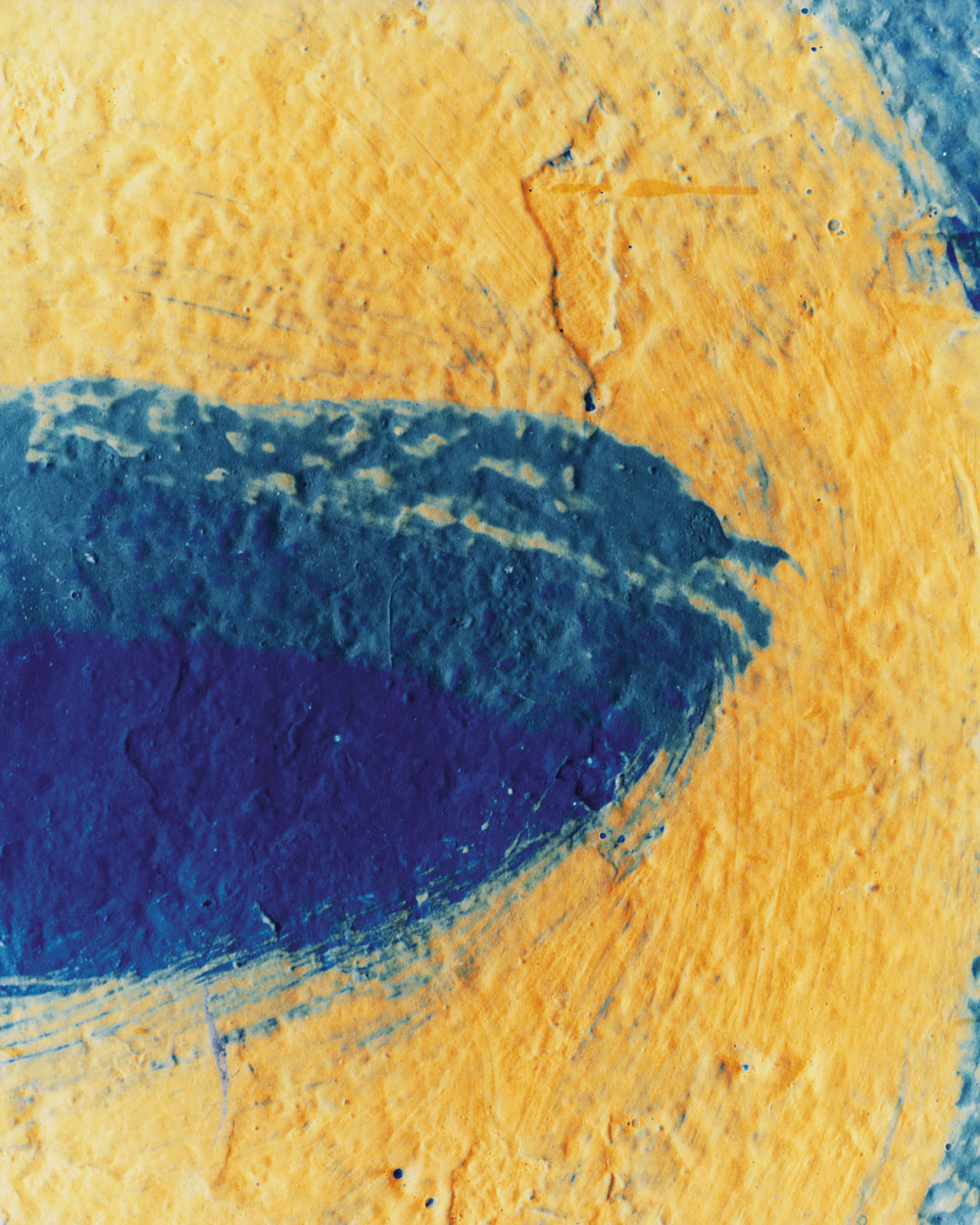

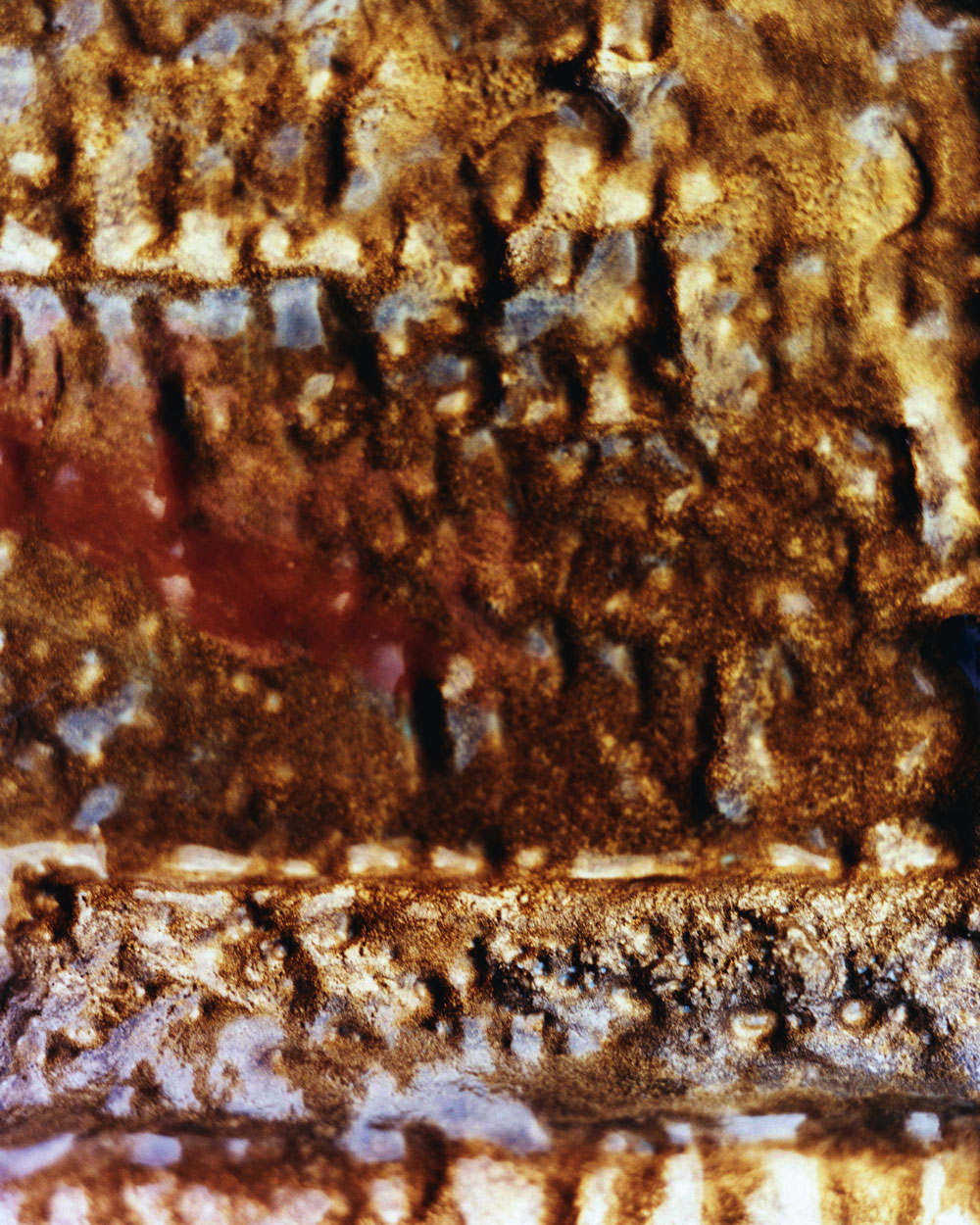

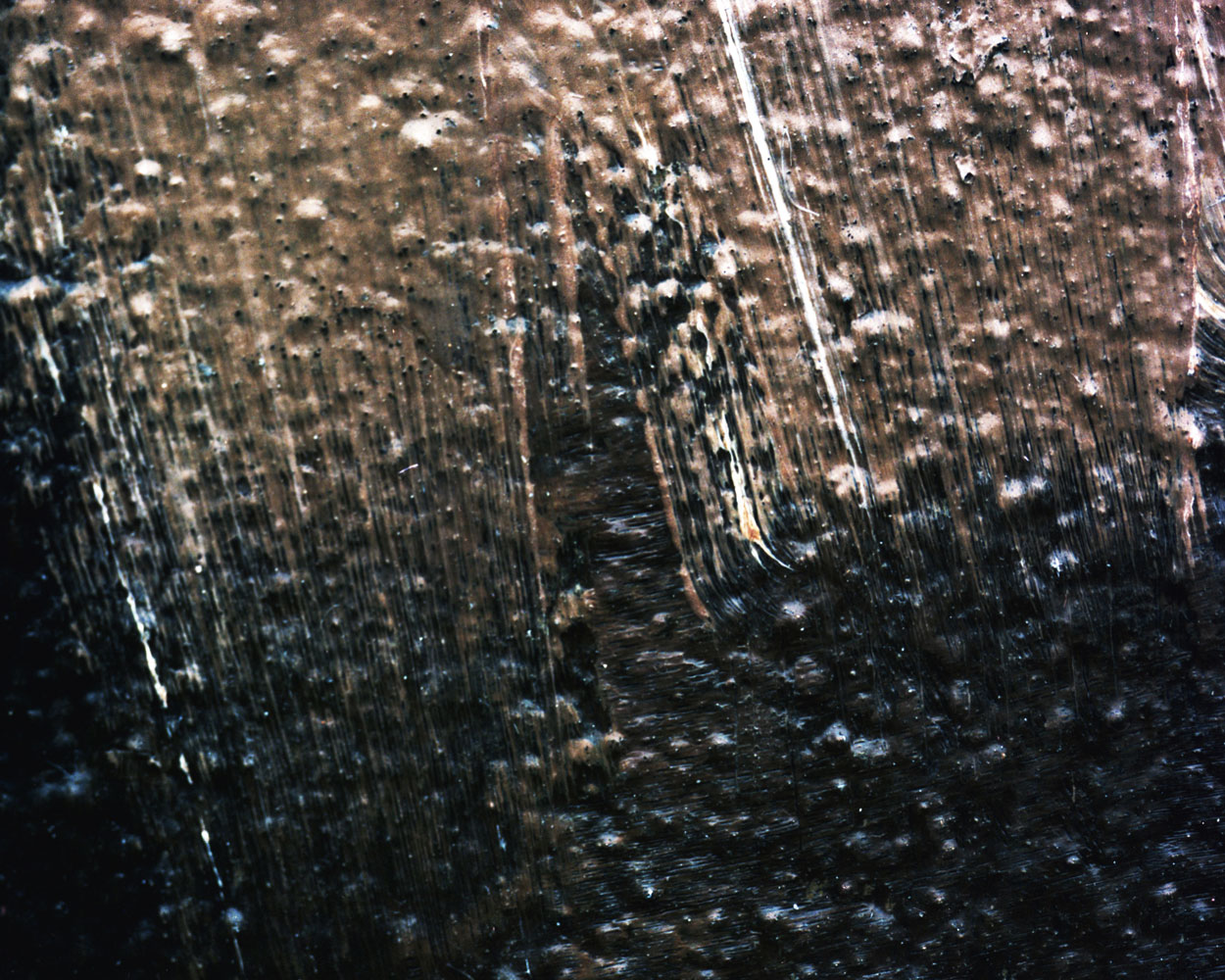

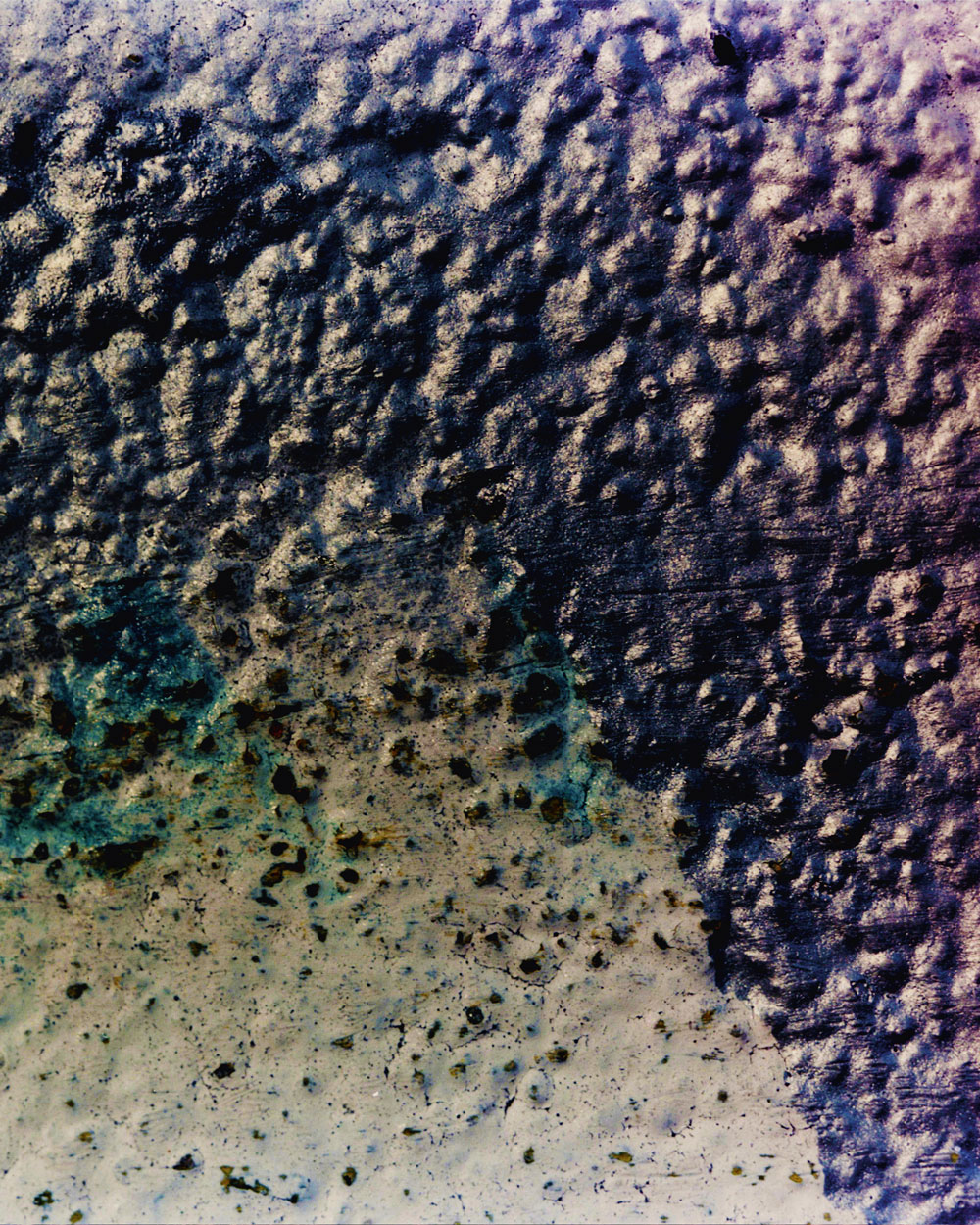

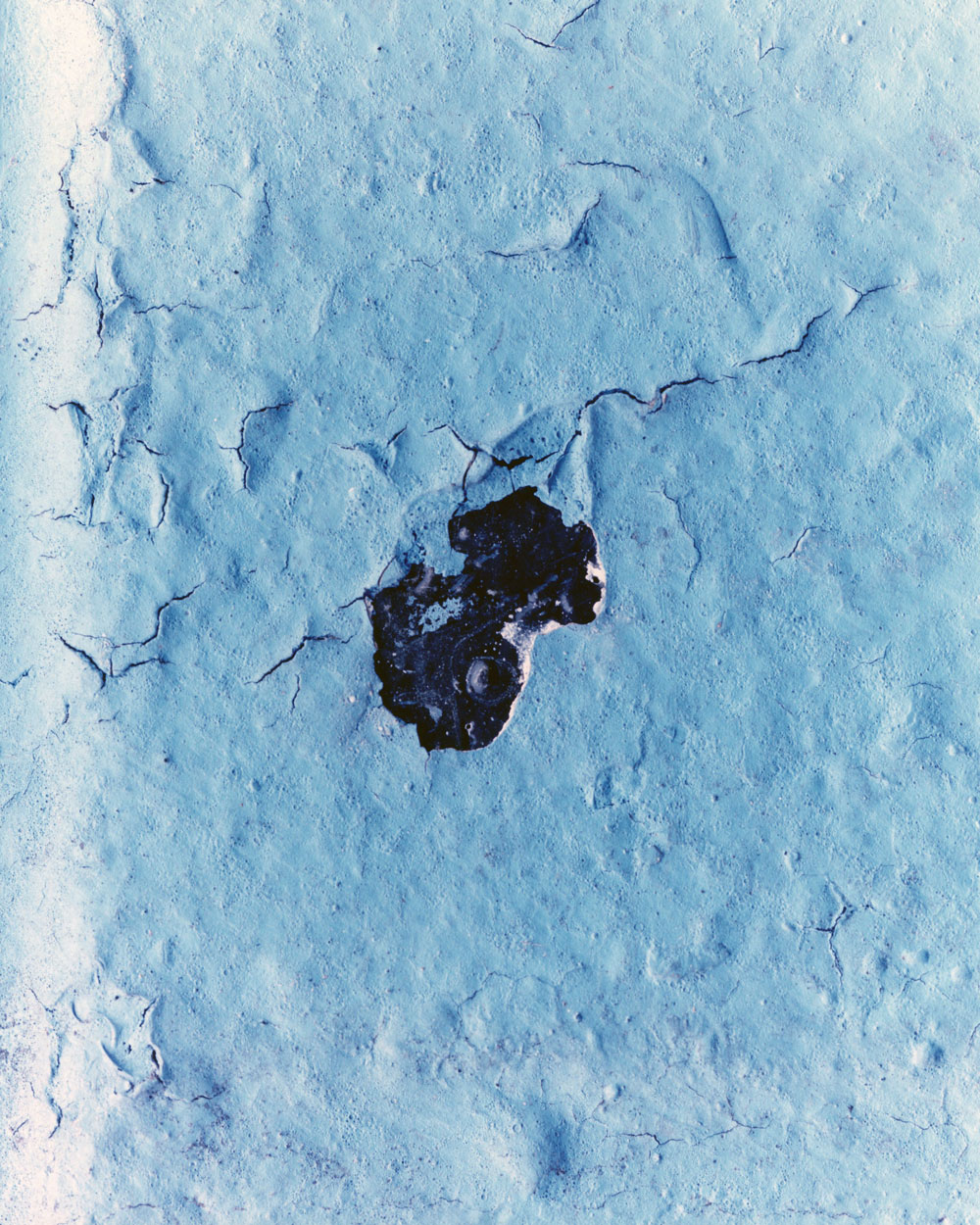

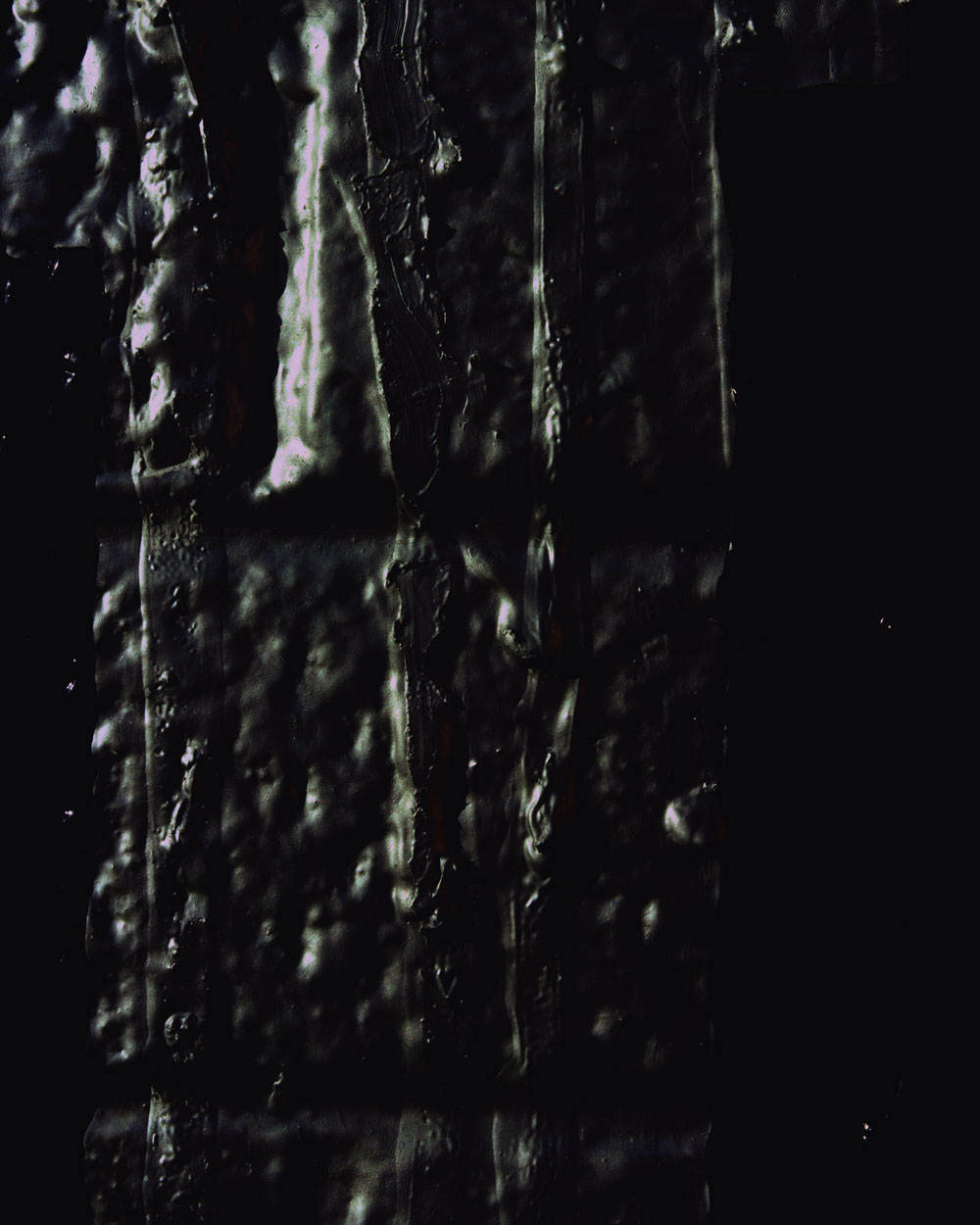

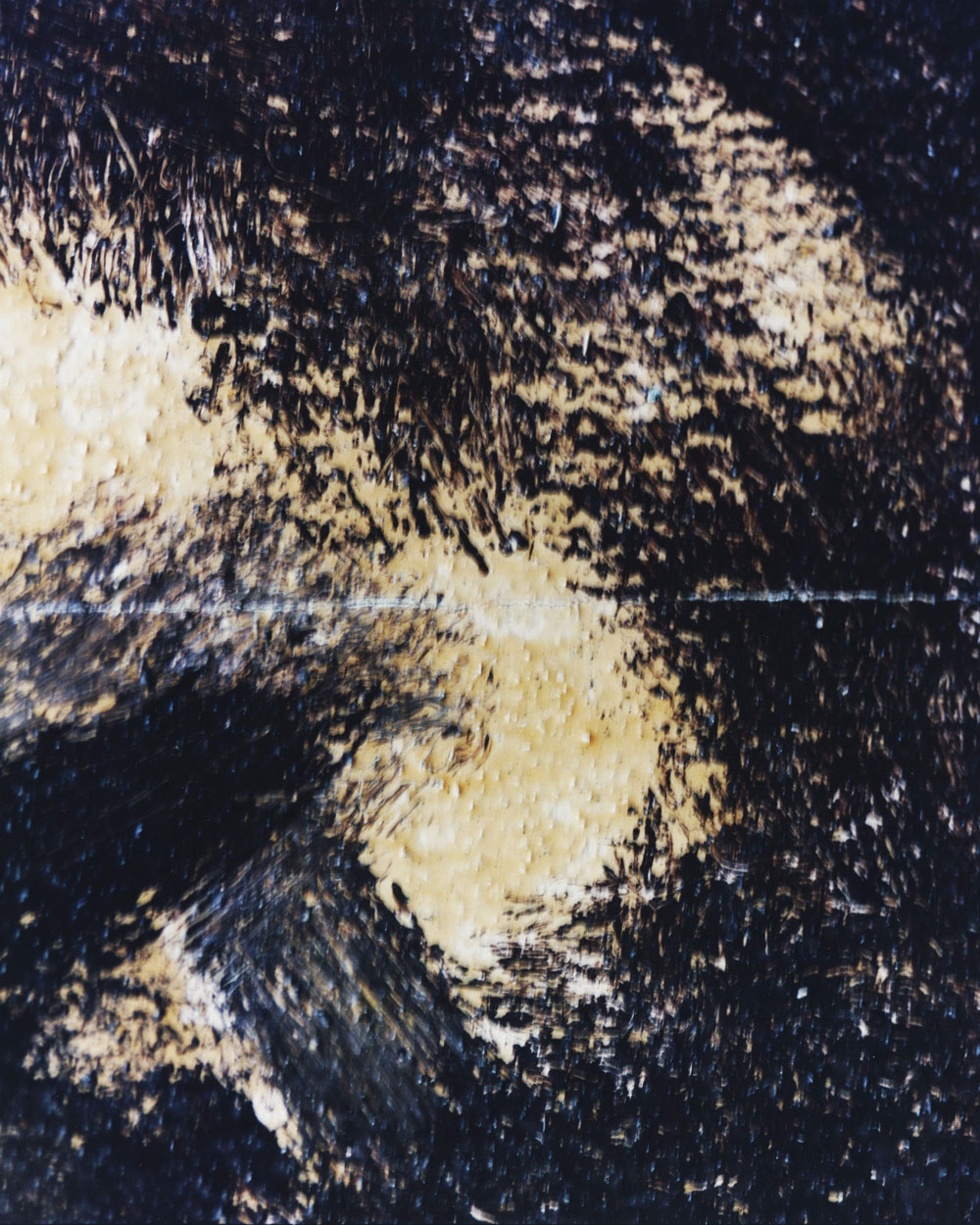

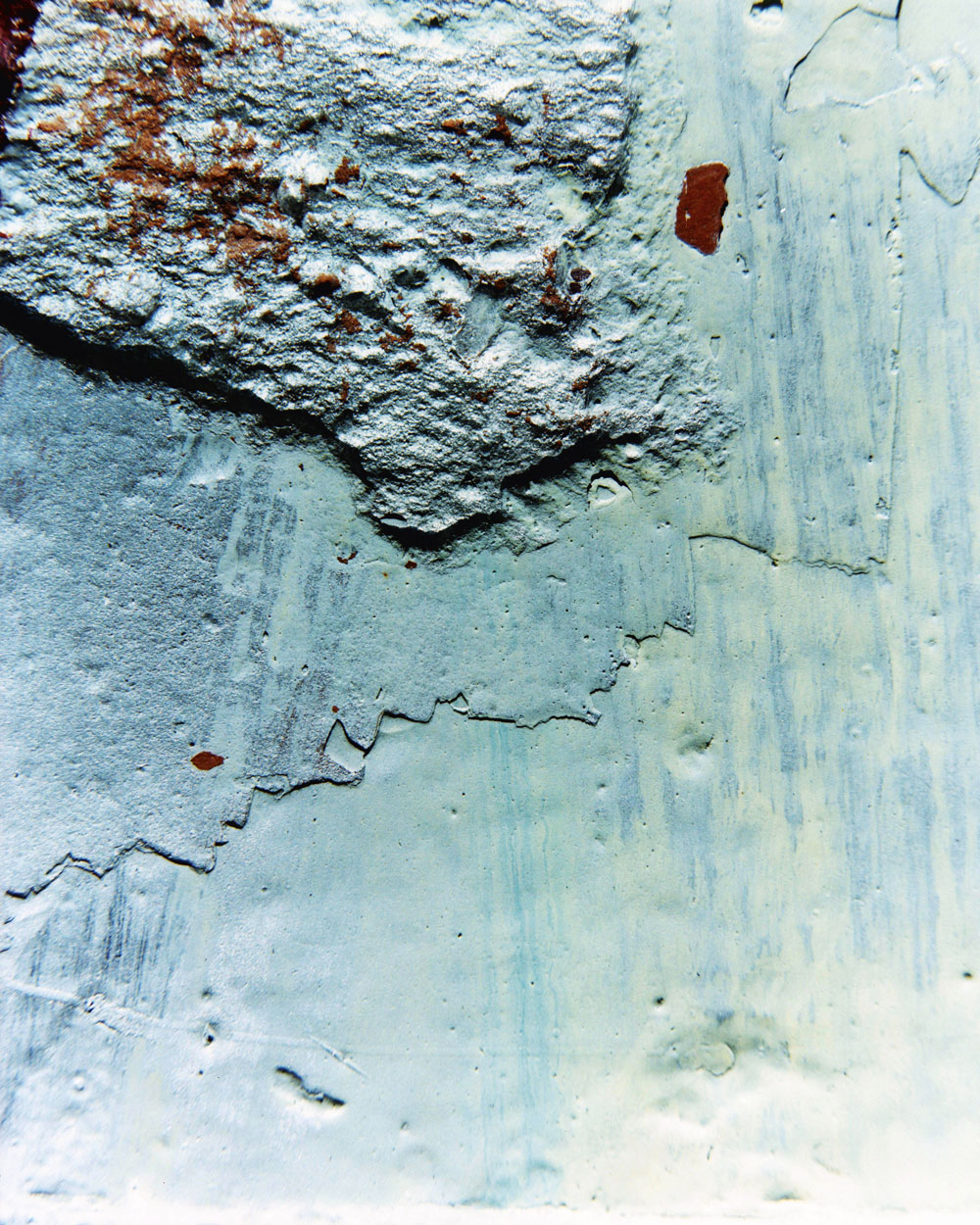

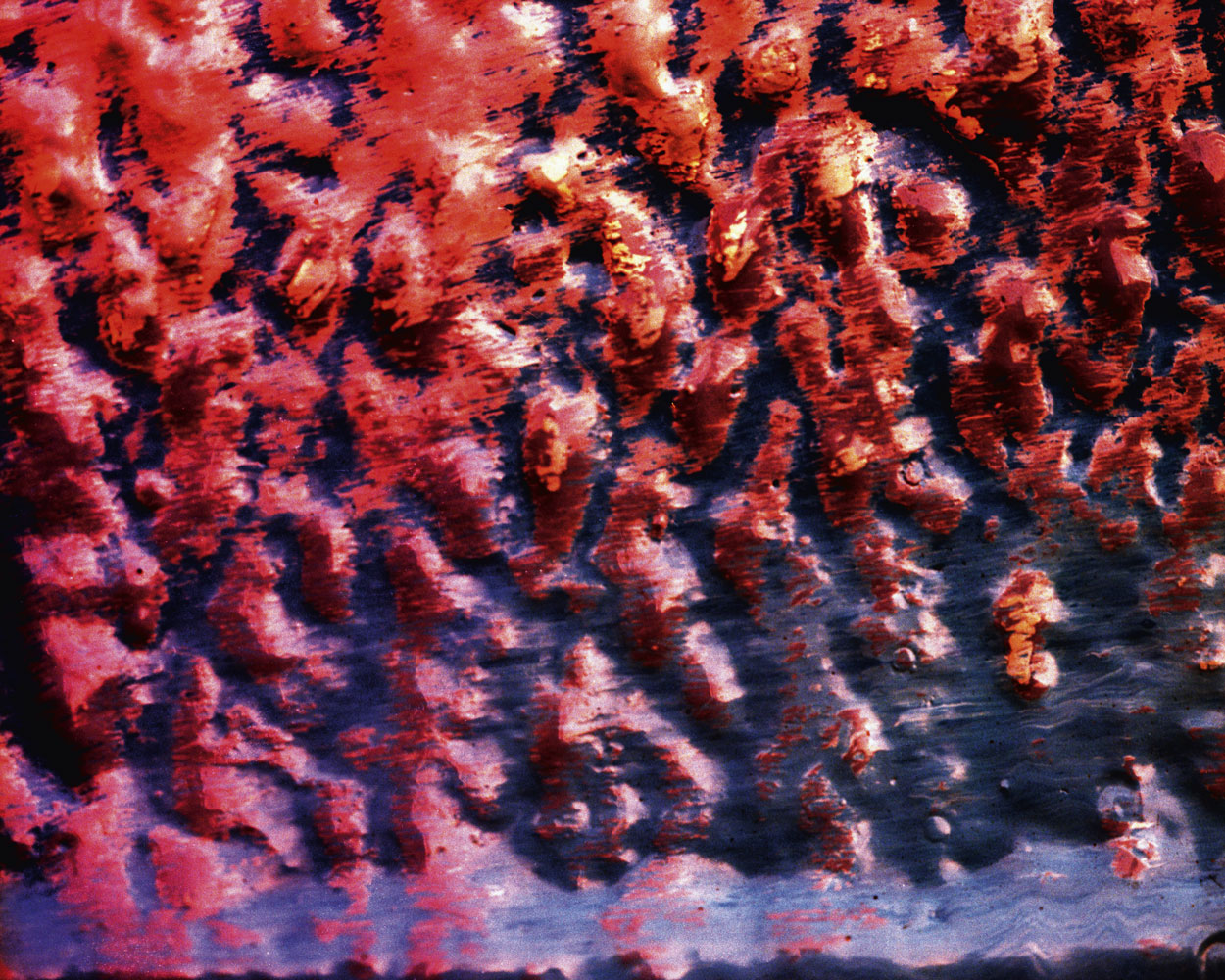

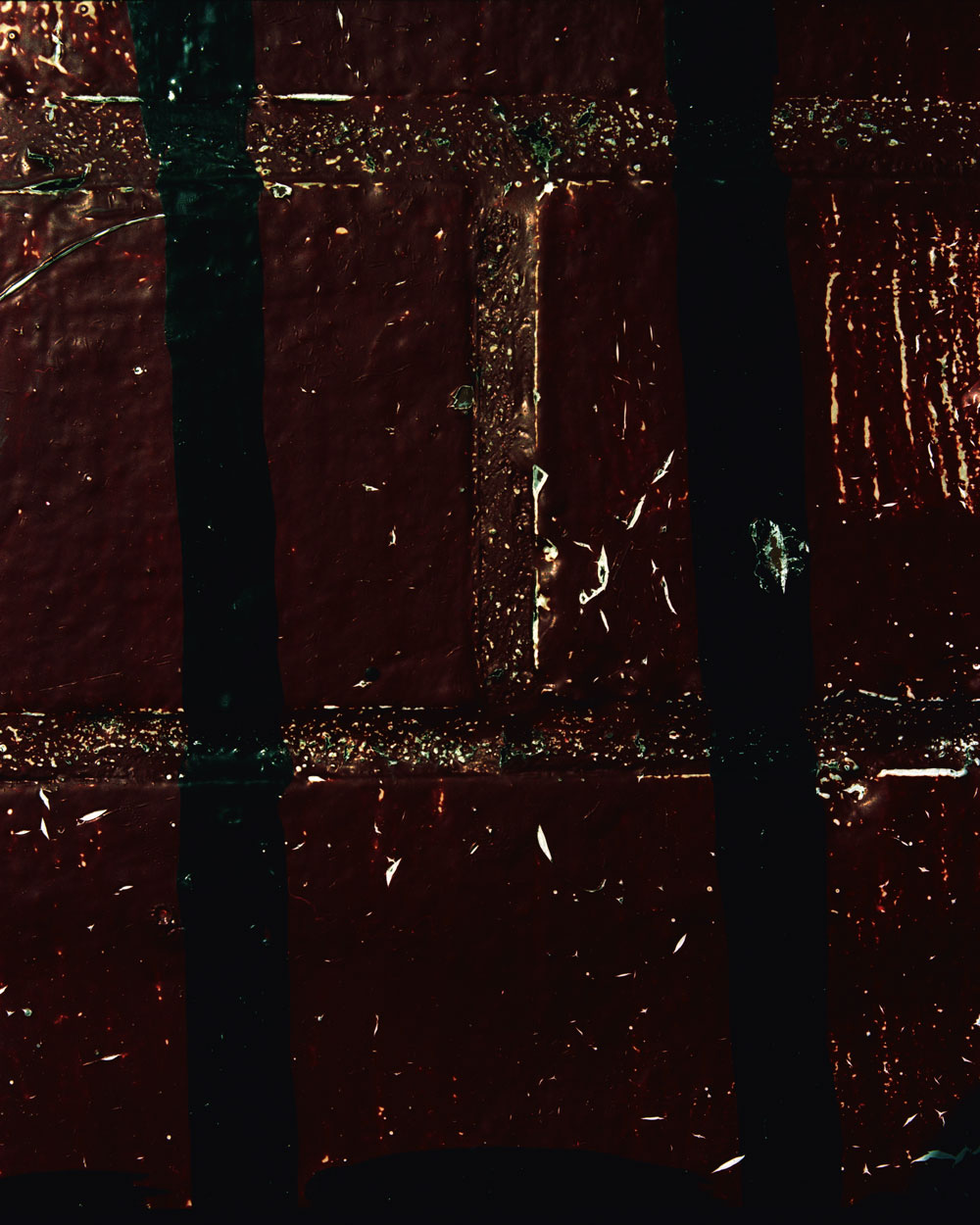

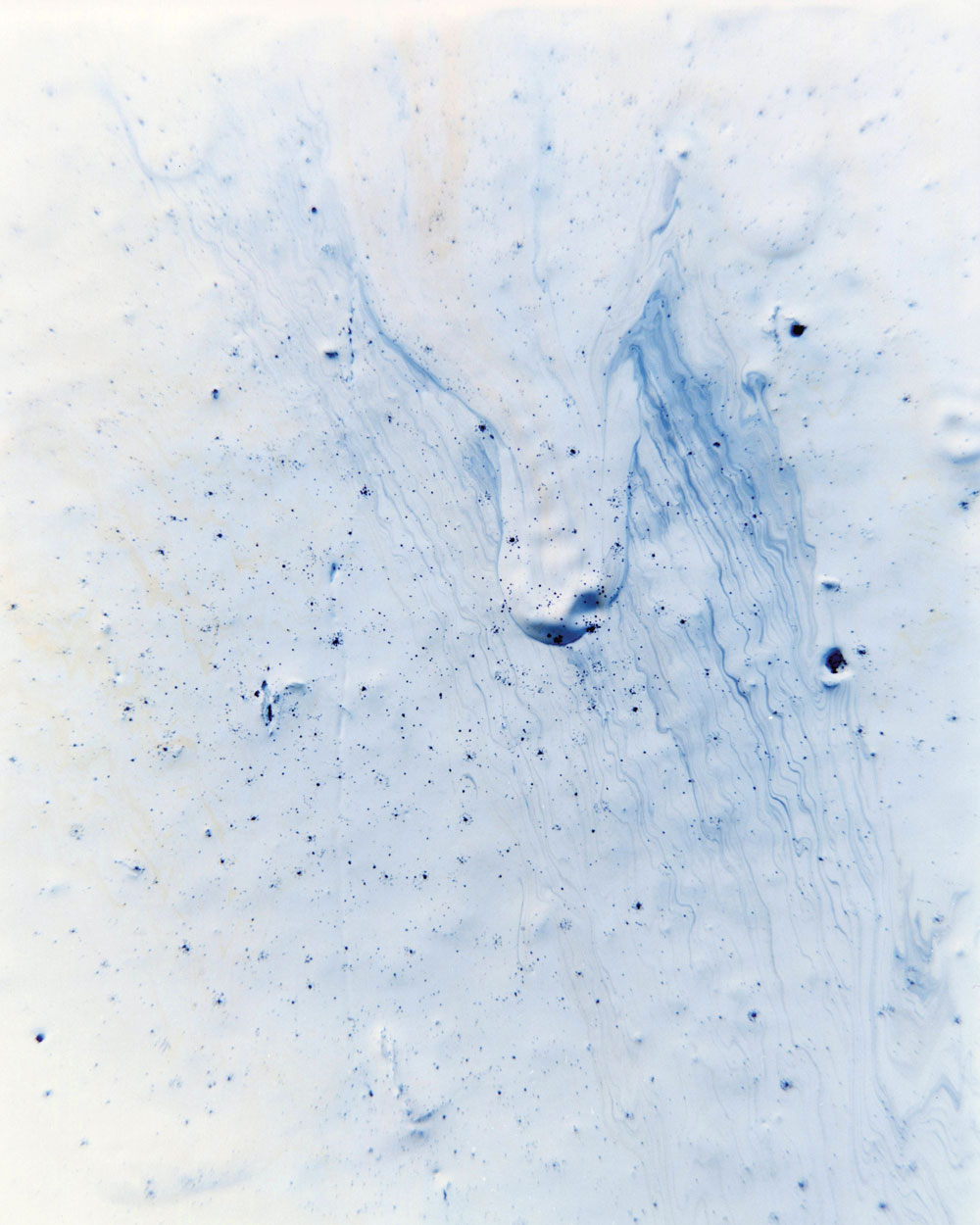

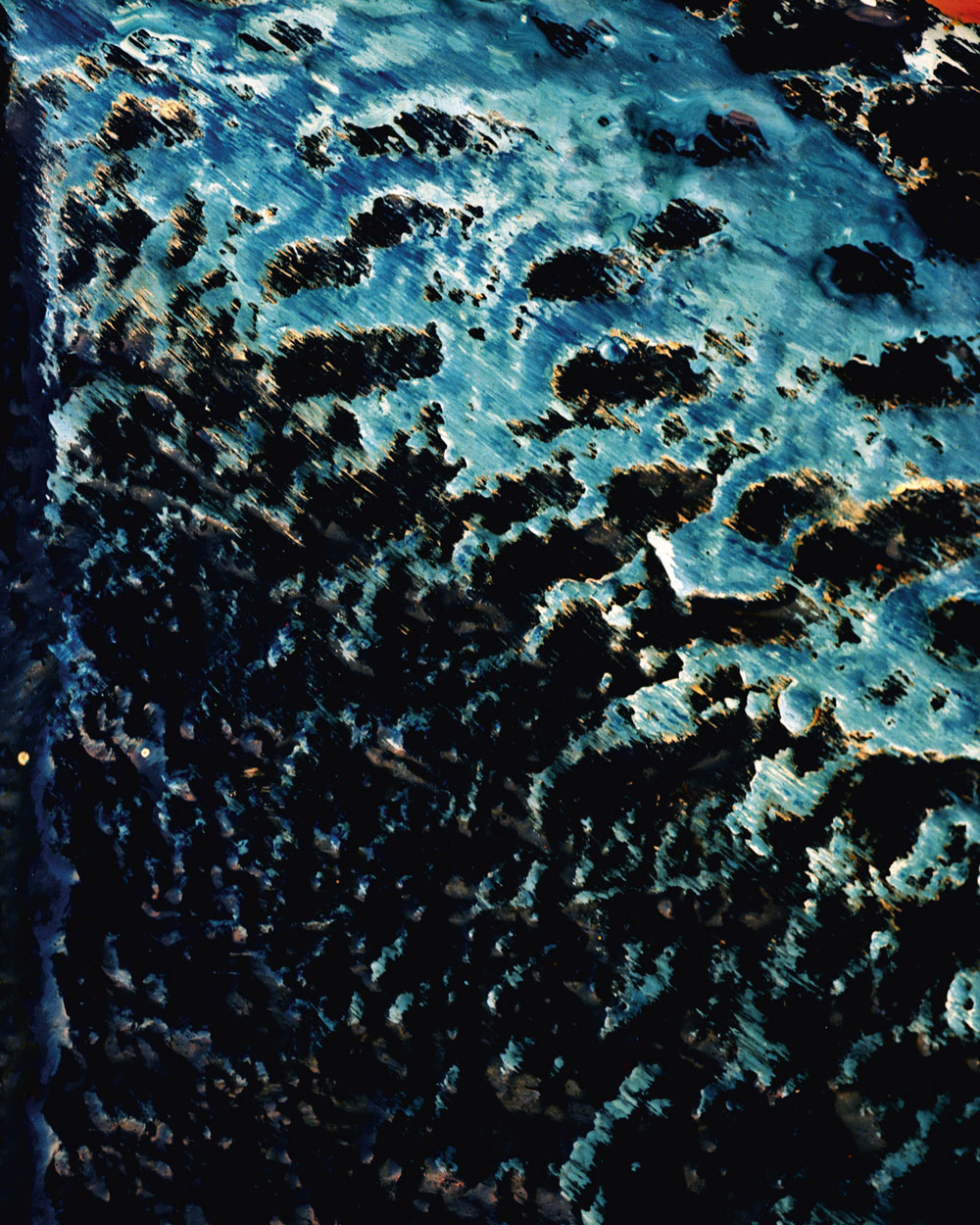

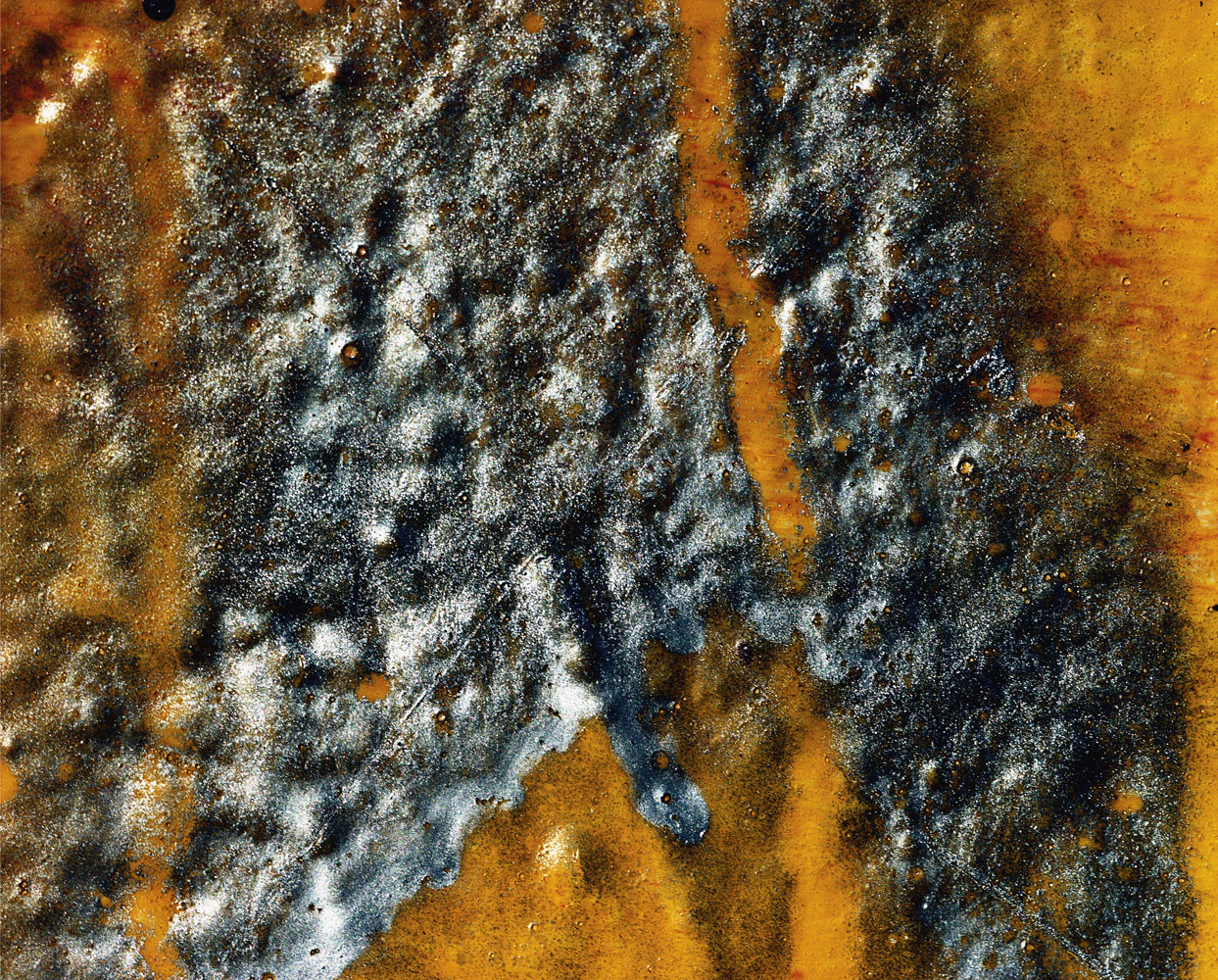

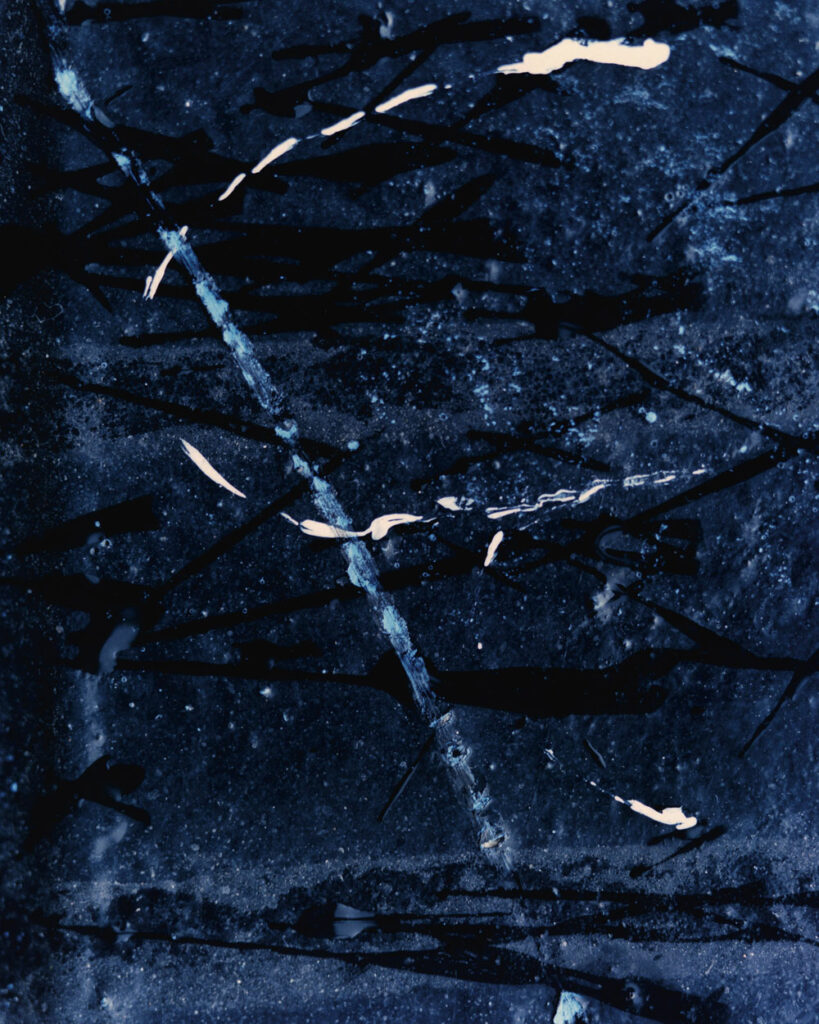

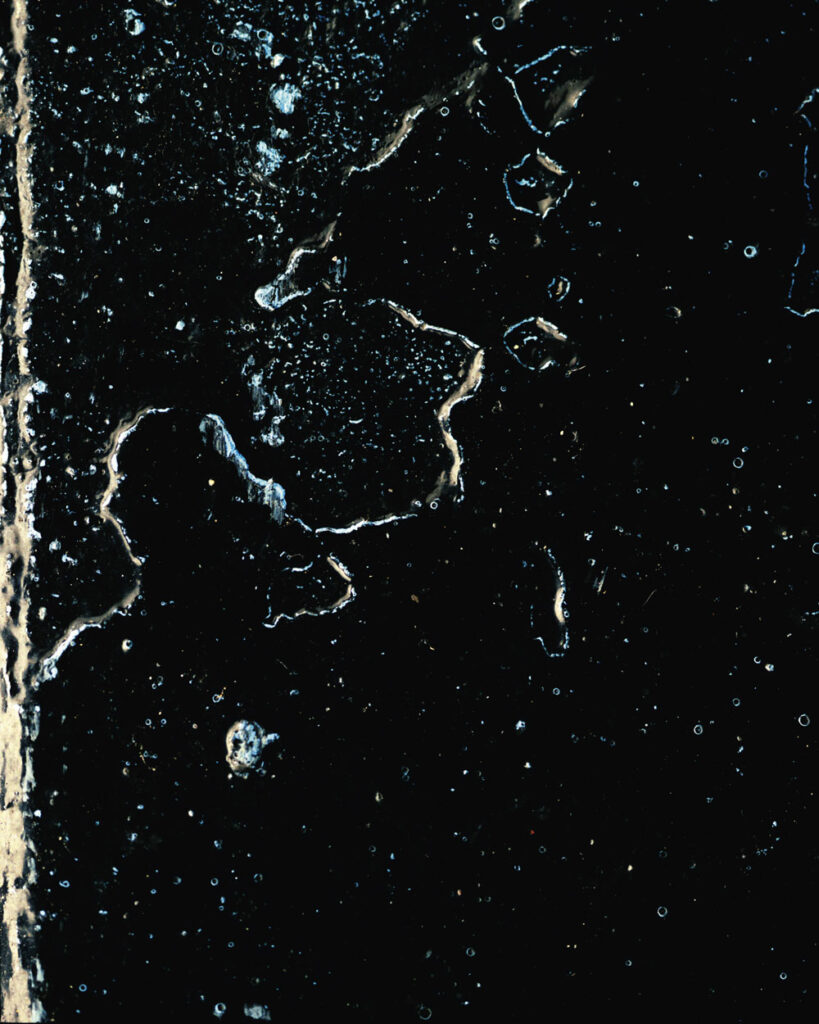

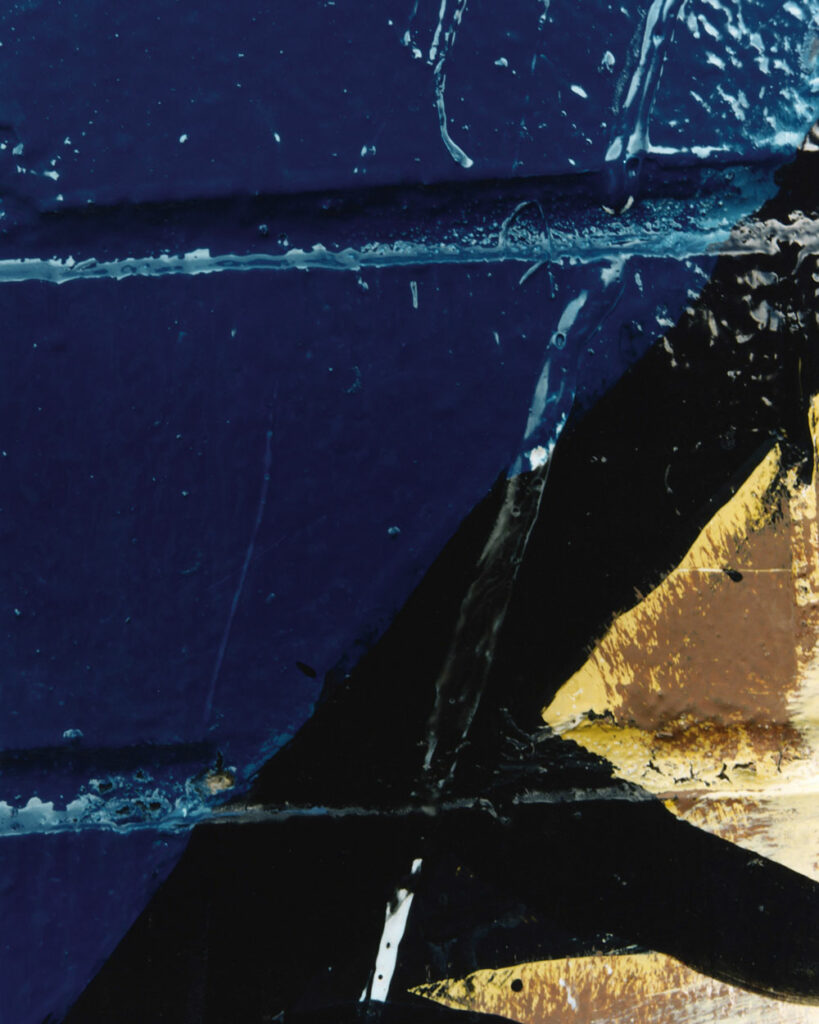

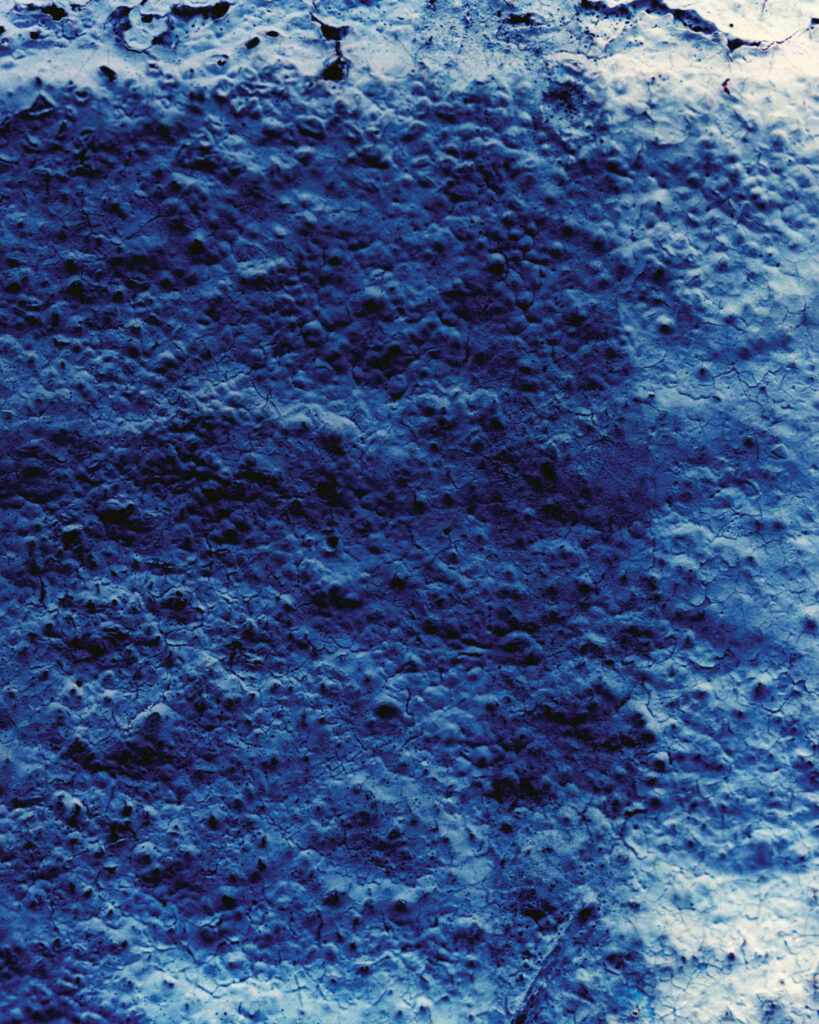

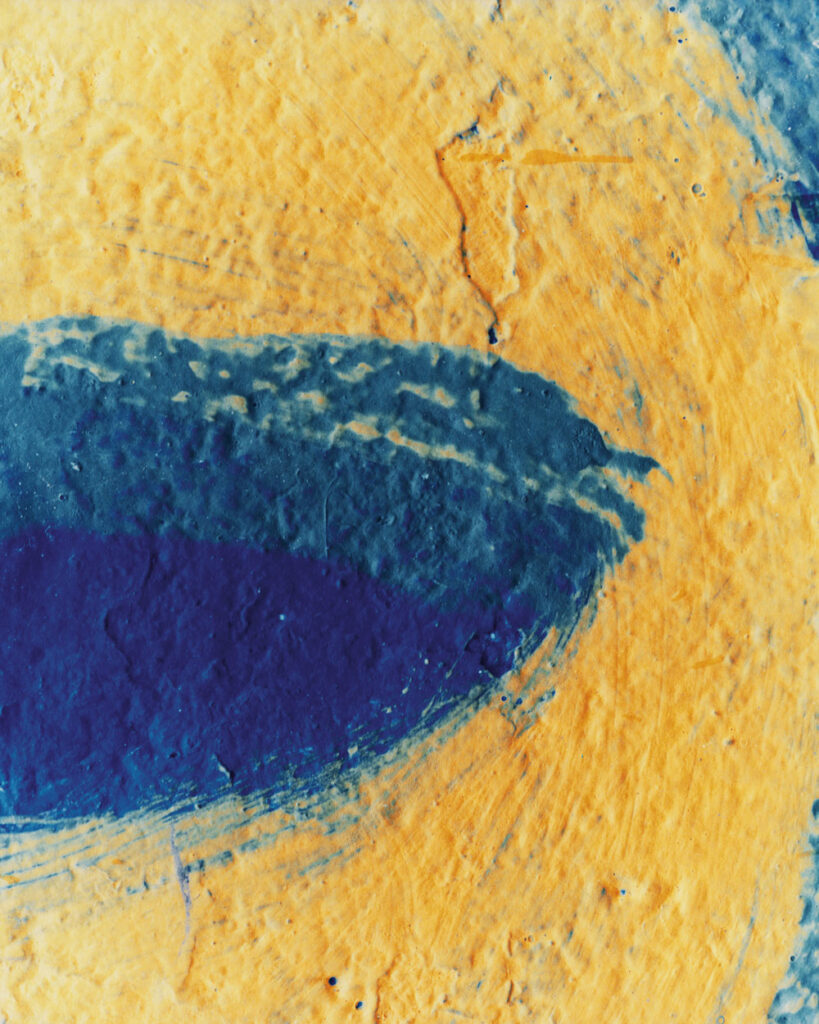

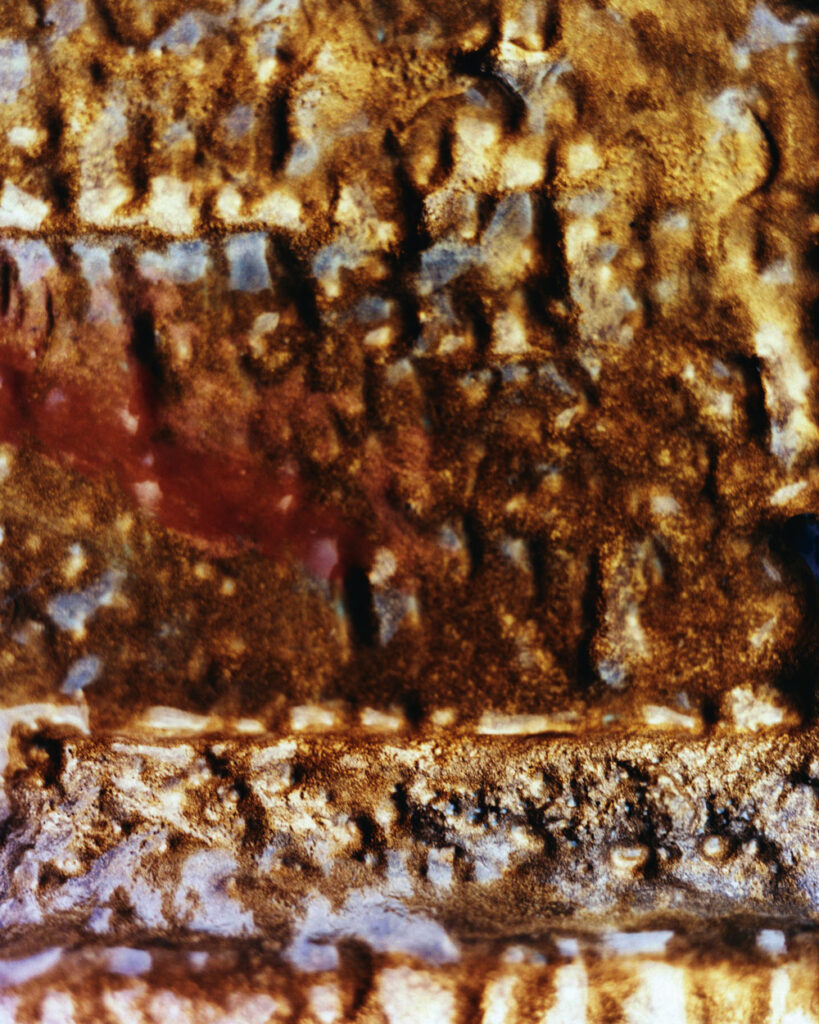

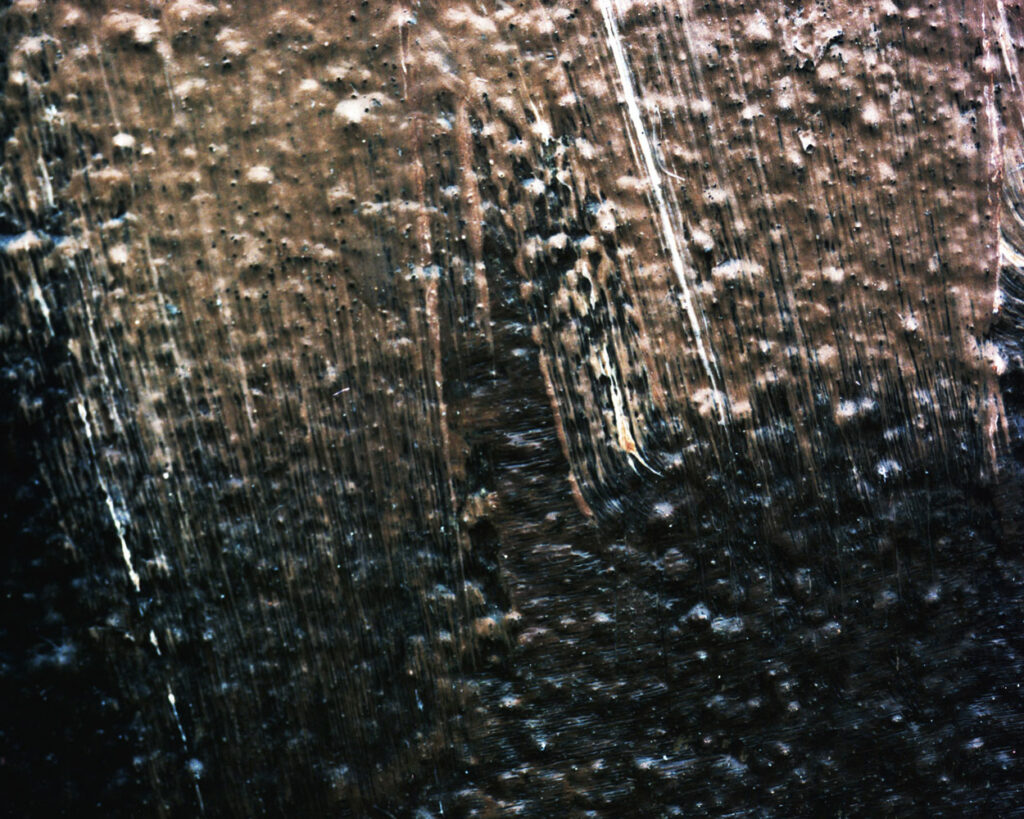

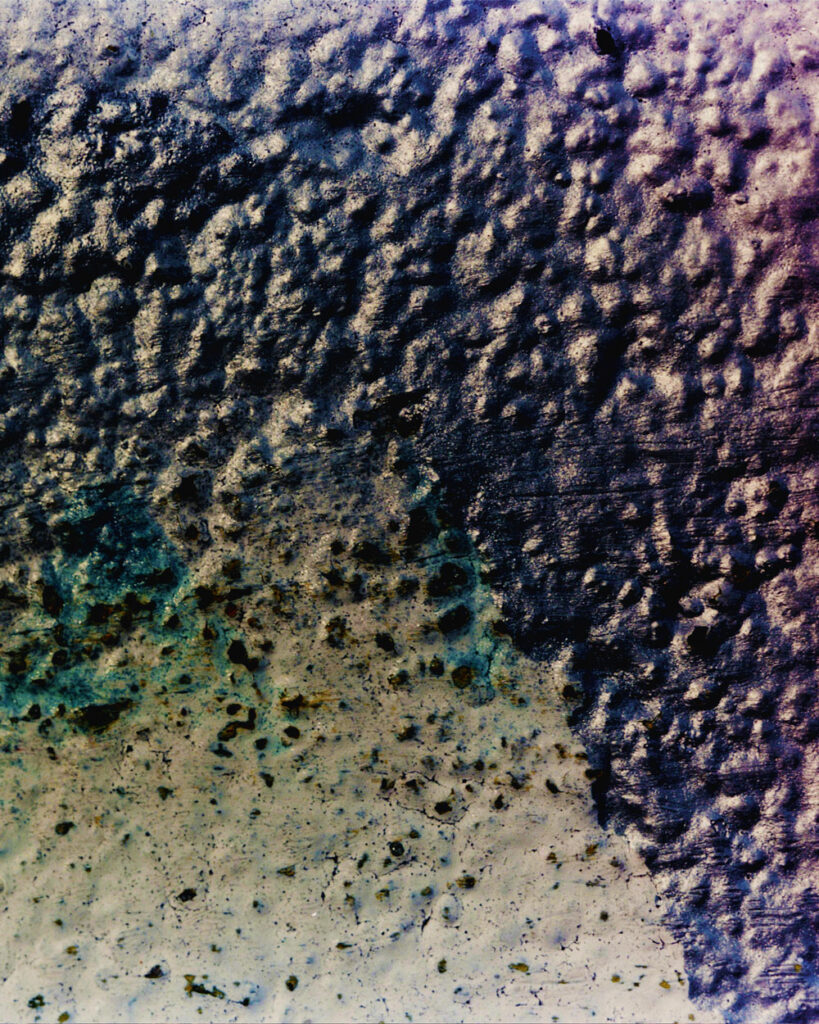

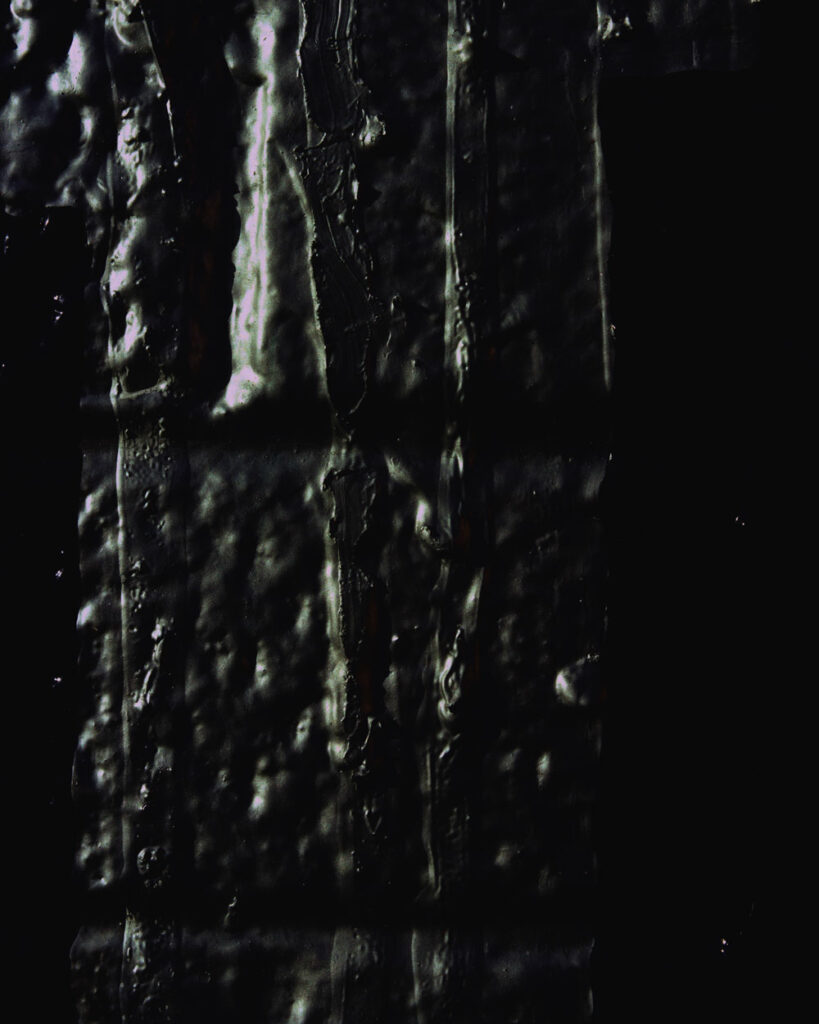

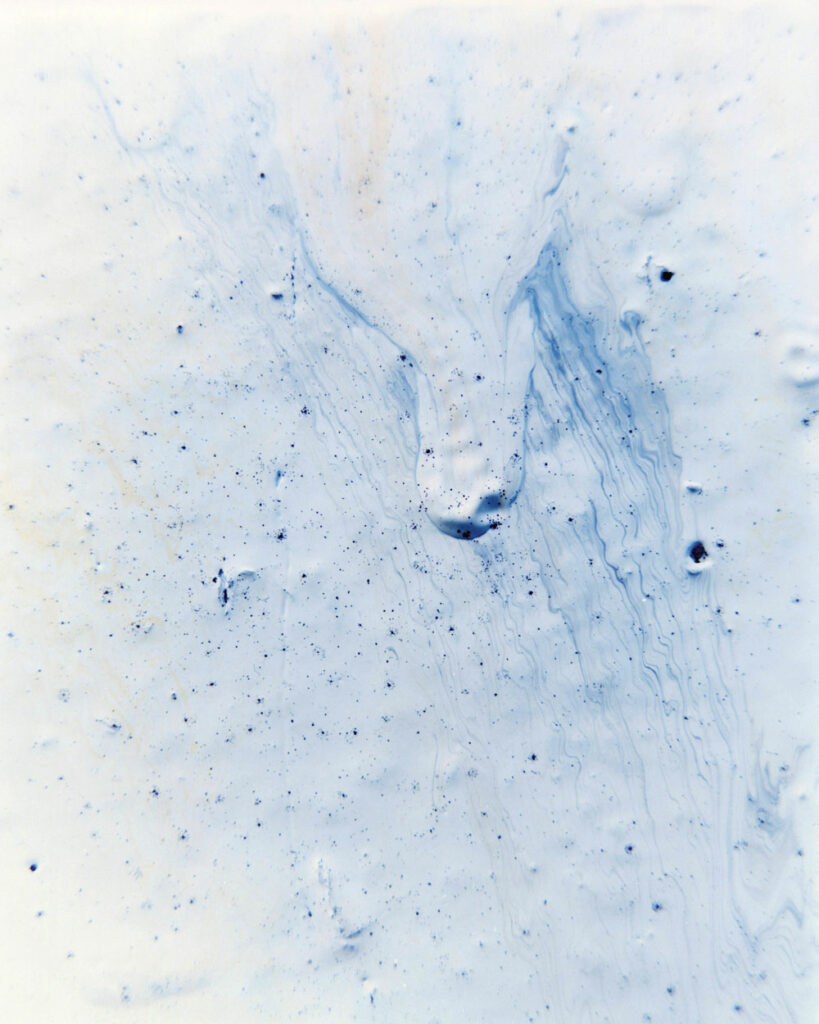

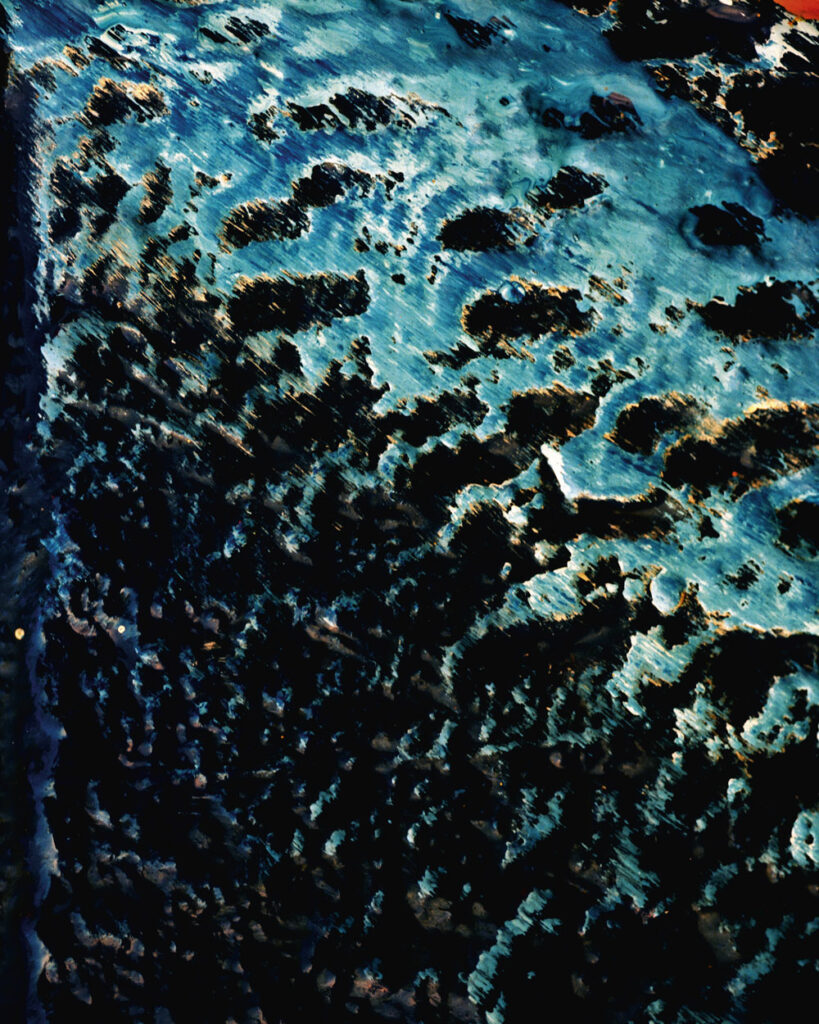

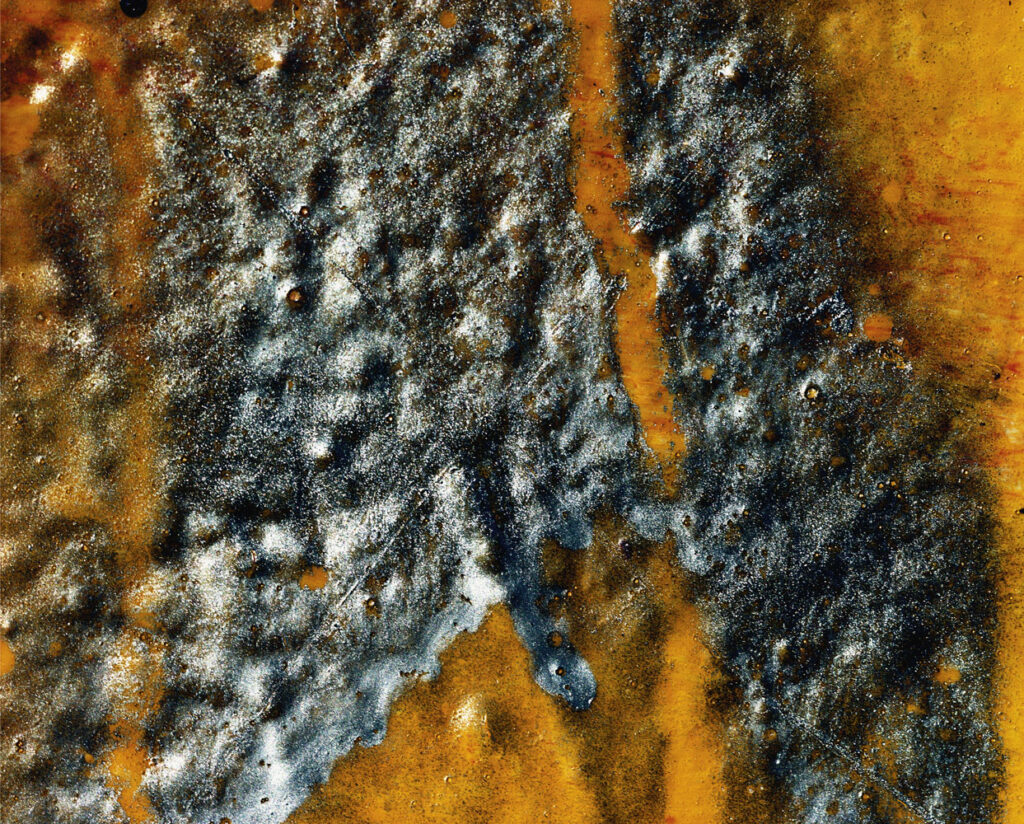

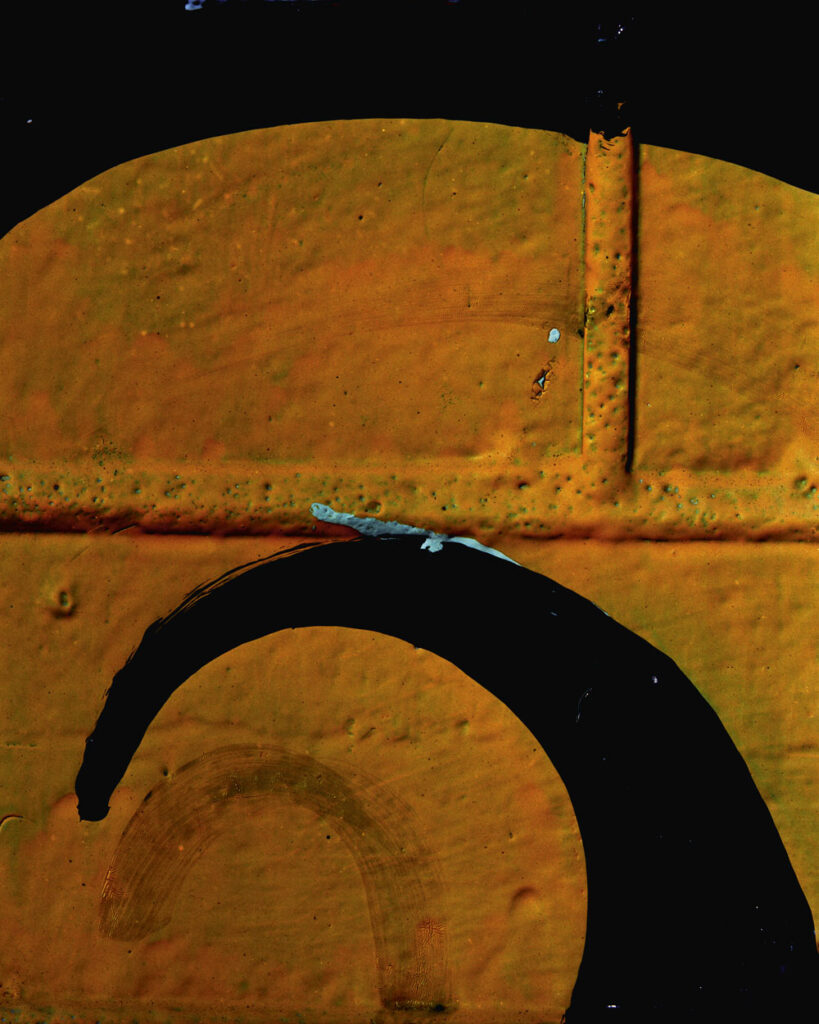

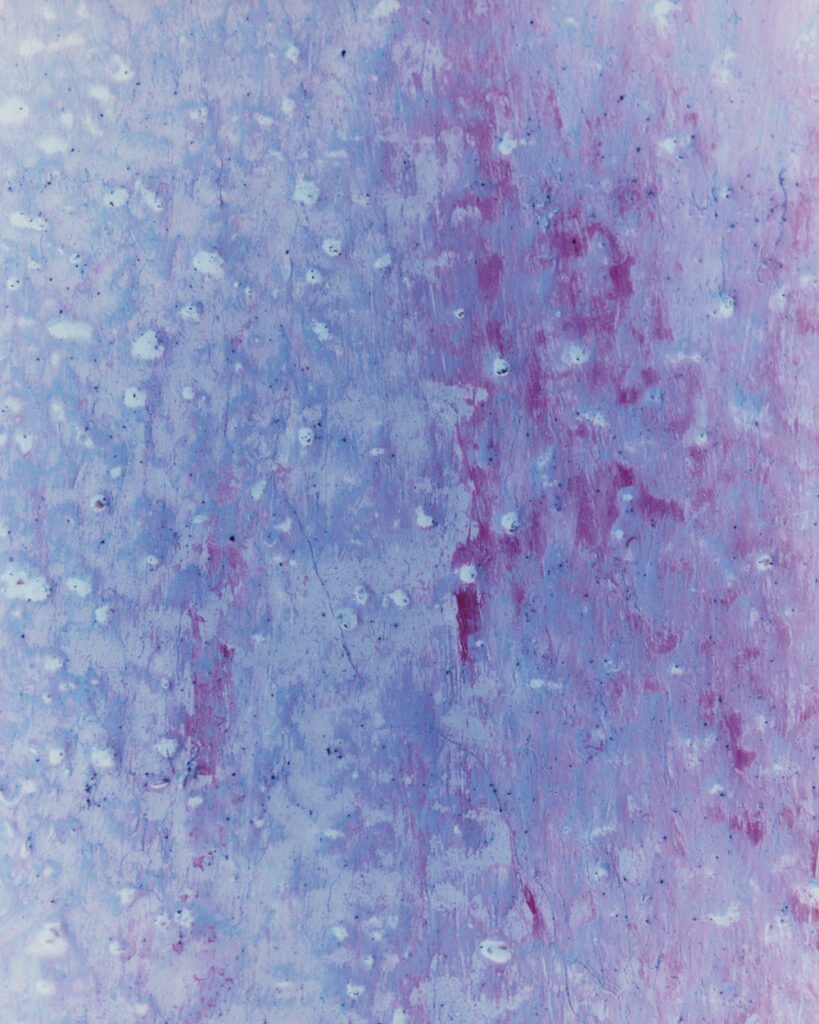

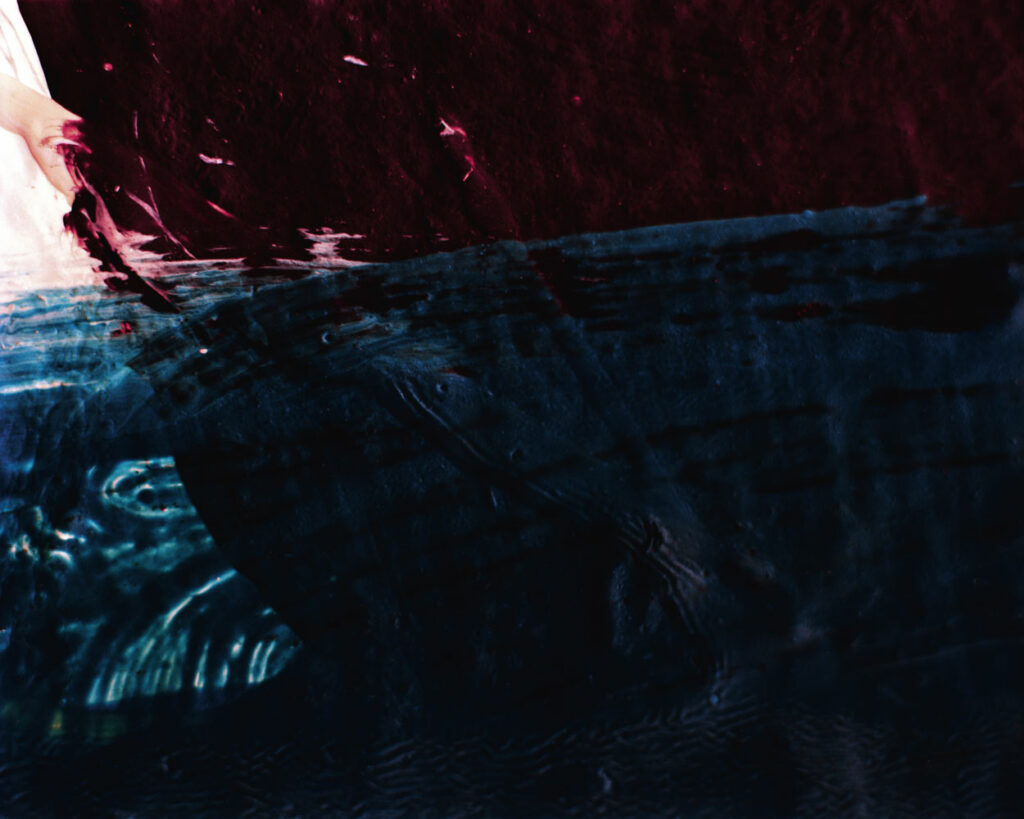

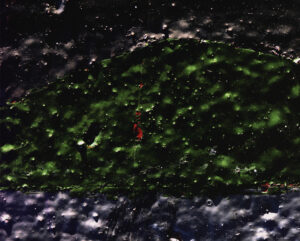

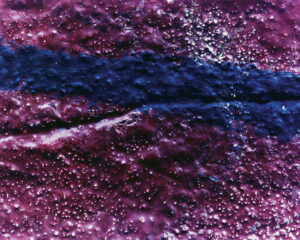

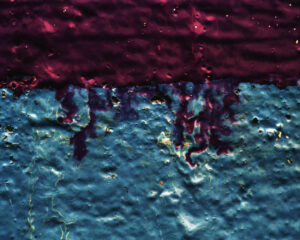

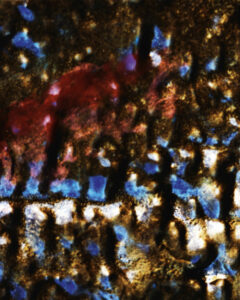

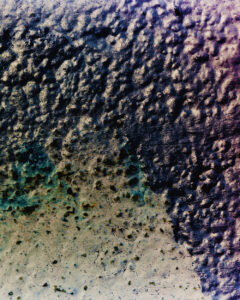

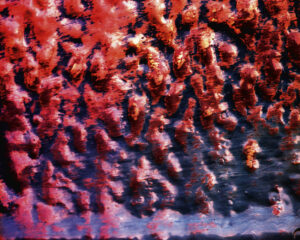

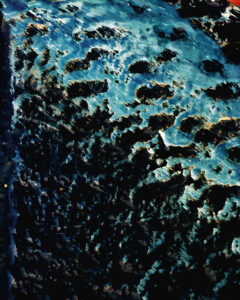

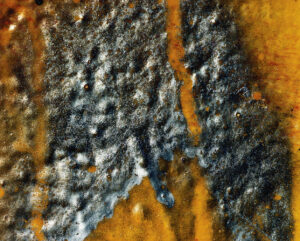

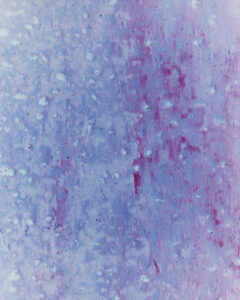

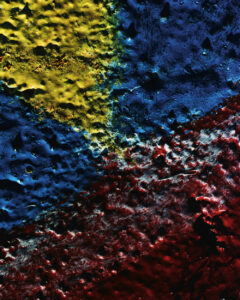

From 1997-99 Gareth McConnell took a series of tightly-cropped, highly focused photographs of small areas of murals. Exhibited in 2003 and 2004 in London and Belfast, the Details of Sectarian Murals series focuses on the physical objecthood of the murals rather than their symbolic visual content. The photographs capture every brushstroke, crack, peel and bump in the paint; highly textured and gestural, these fragmented murals feel like crude odes to abstract expressionism. The irregular quality of the walls, the flaking paint, and the rough brushstrokes all emphasize their existence as large-scale, outdoor works frequently, although not always, painted by community volunteers and members of sectarian groups rather than professional artists.

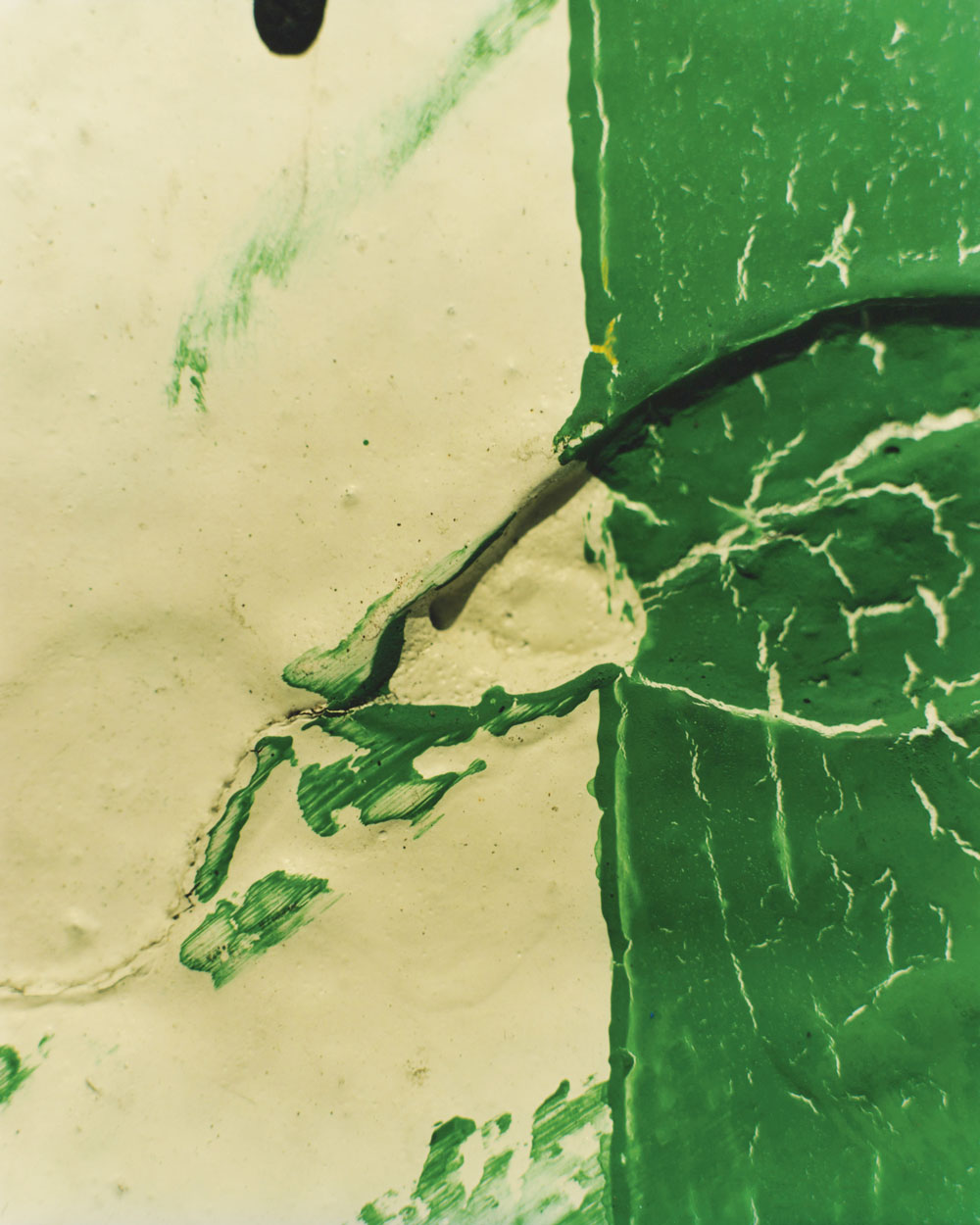

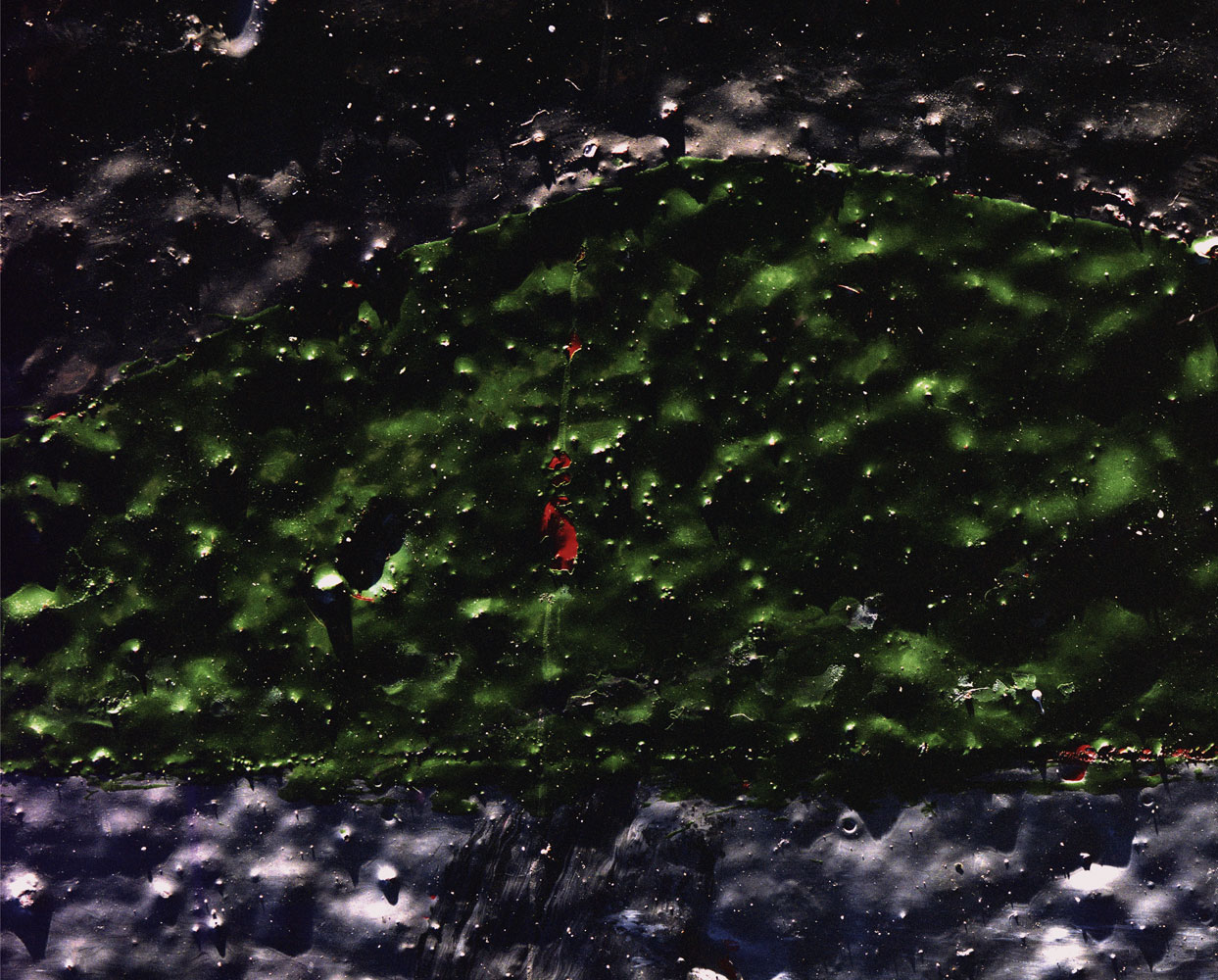

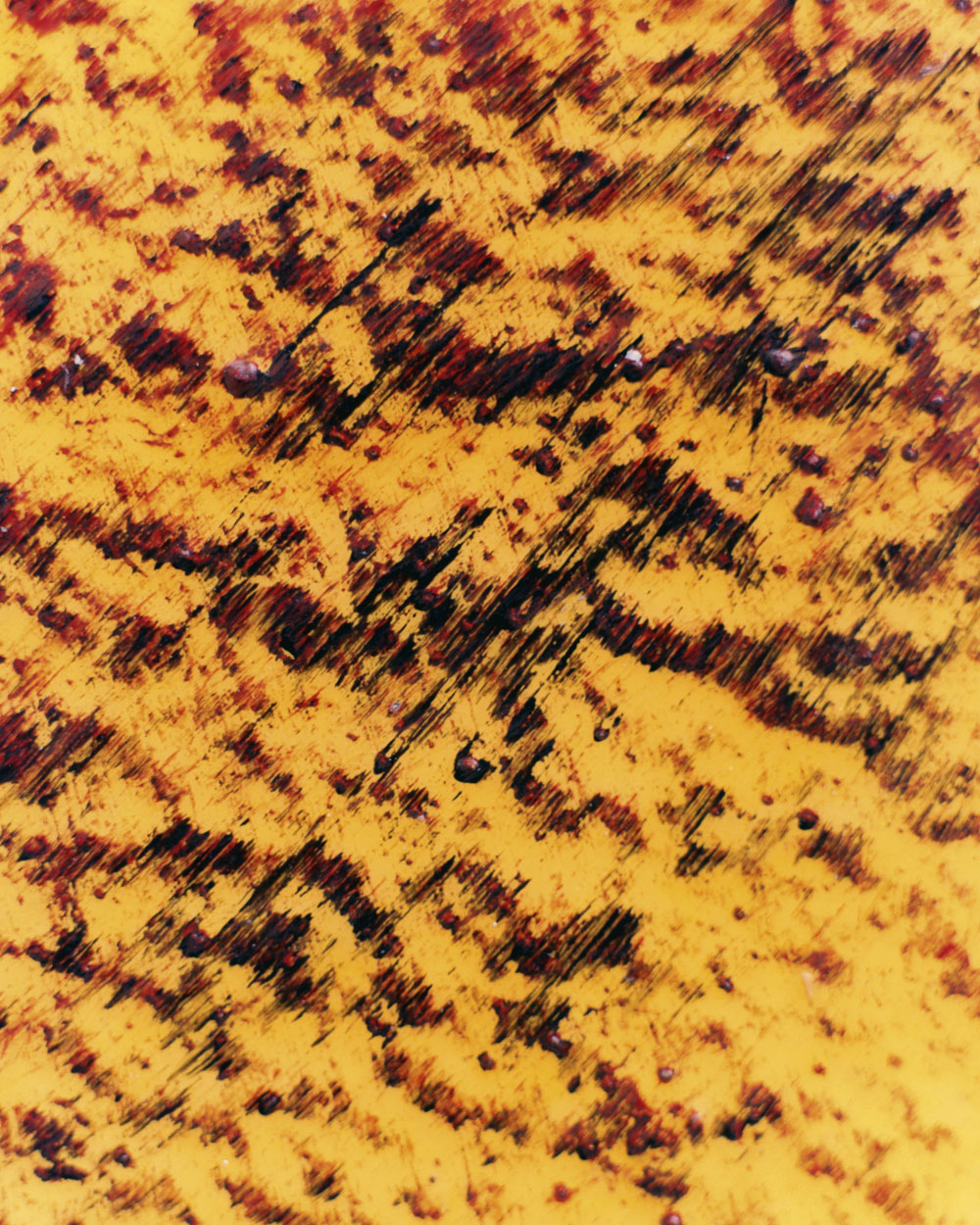

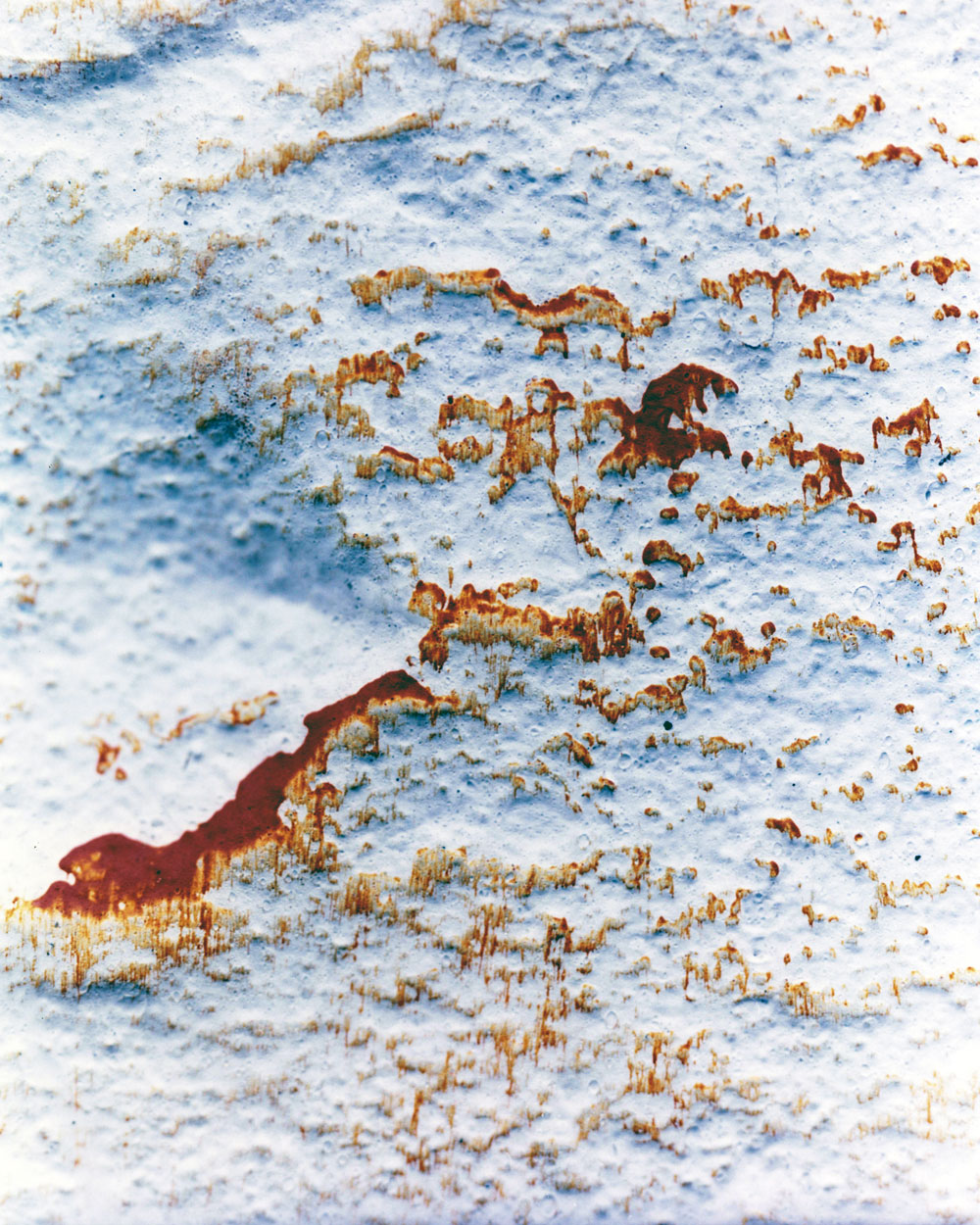

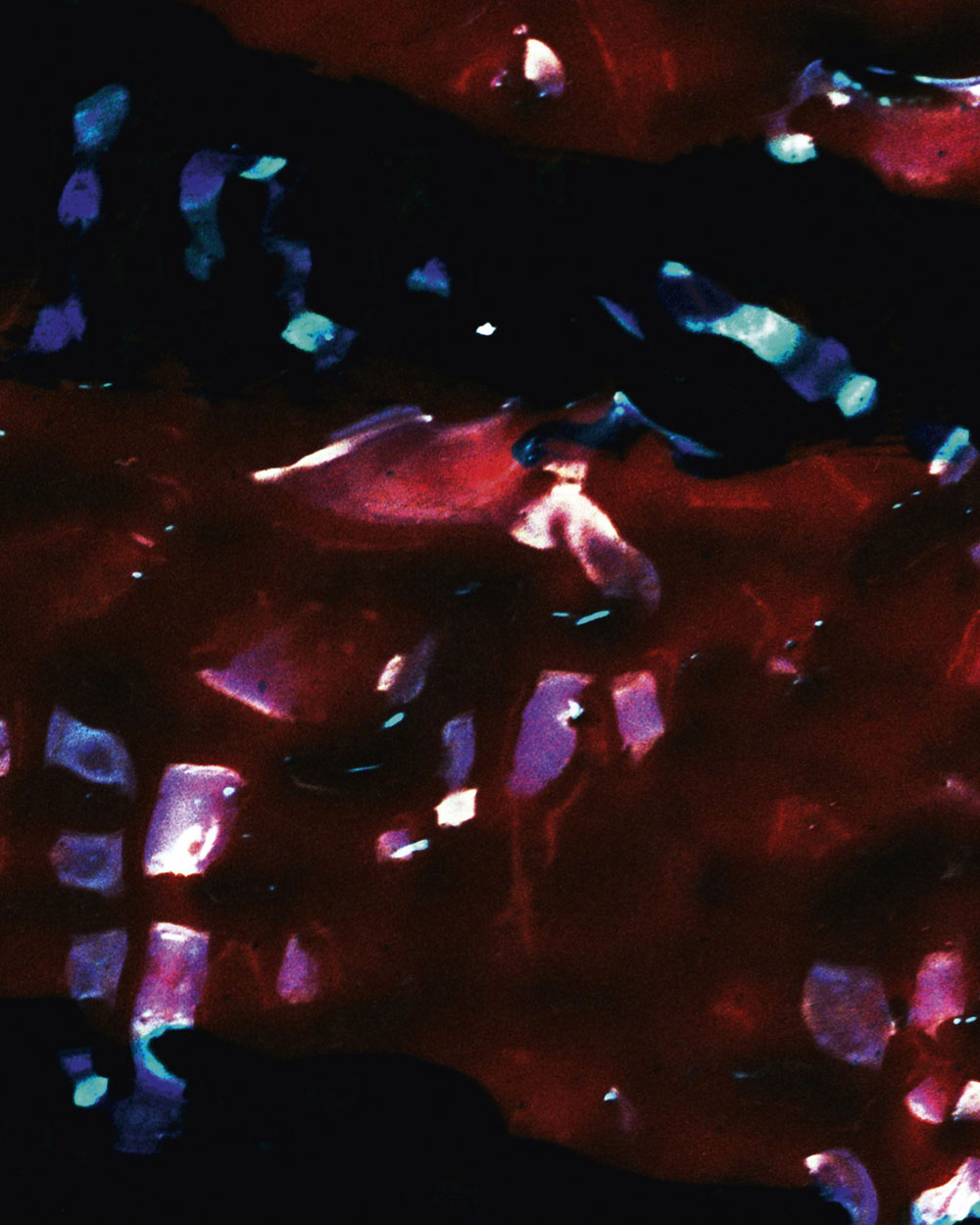

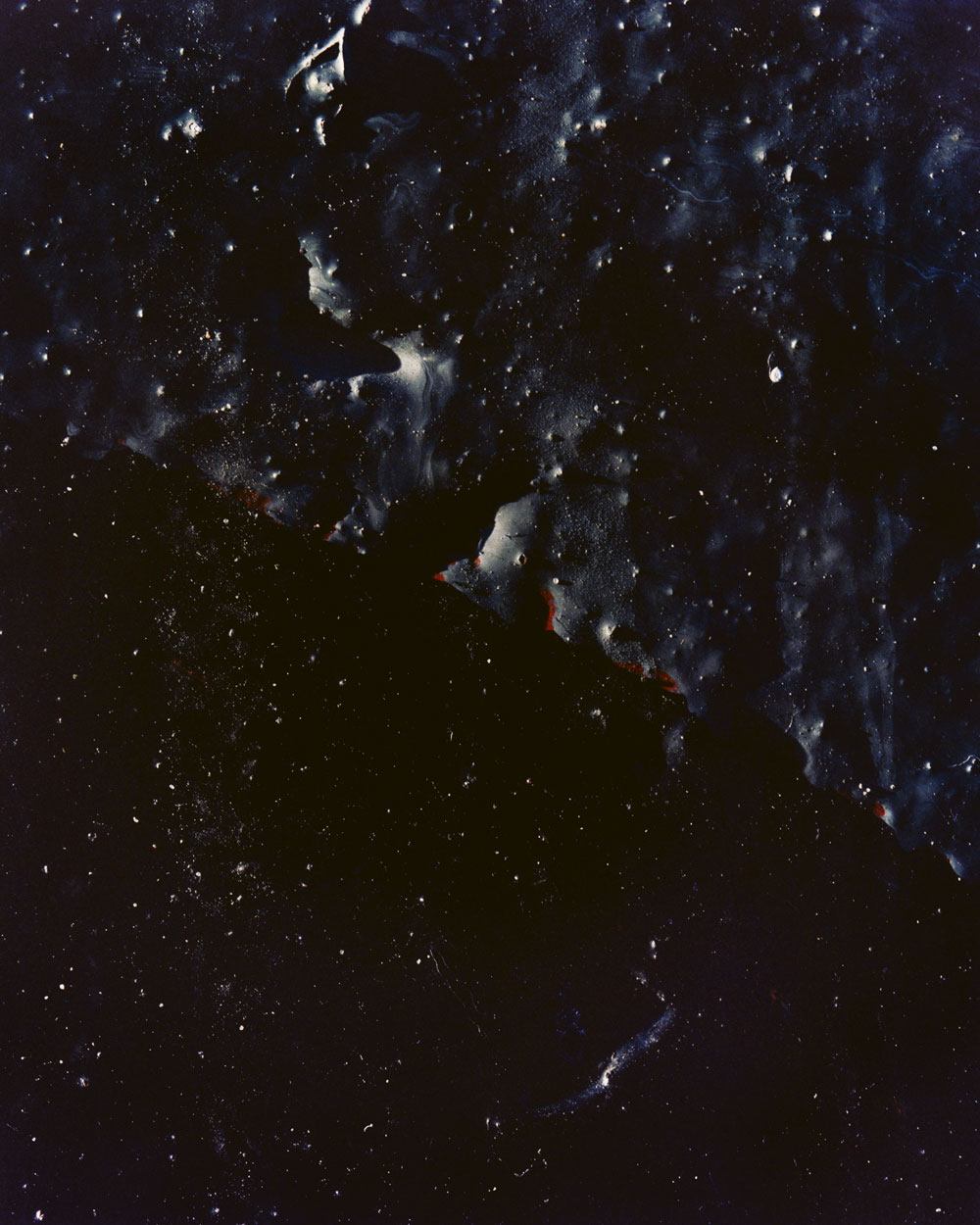

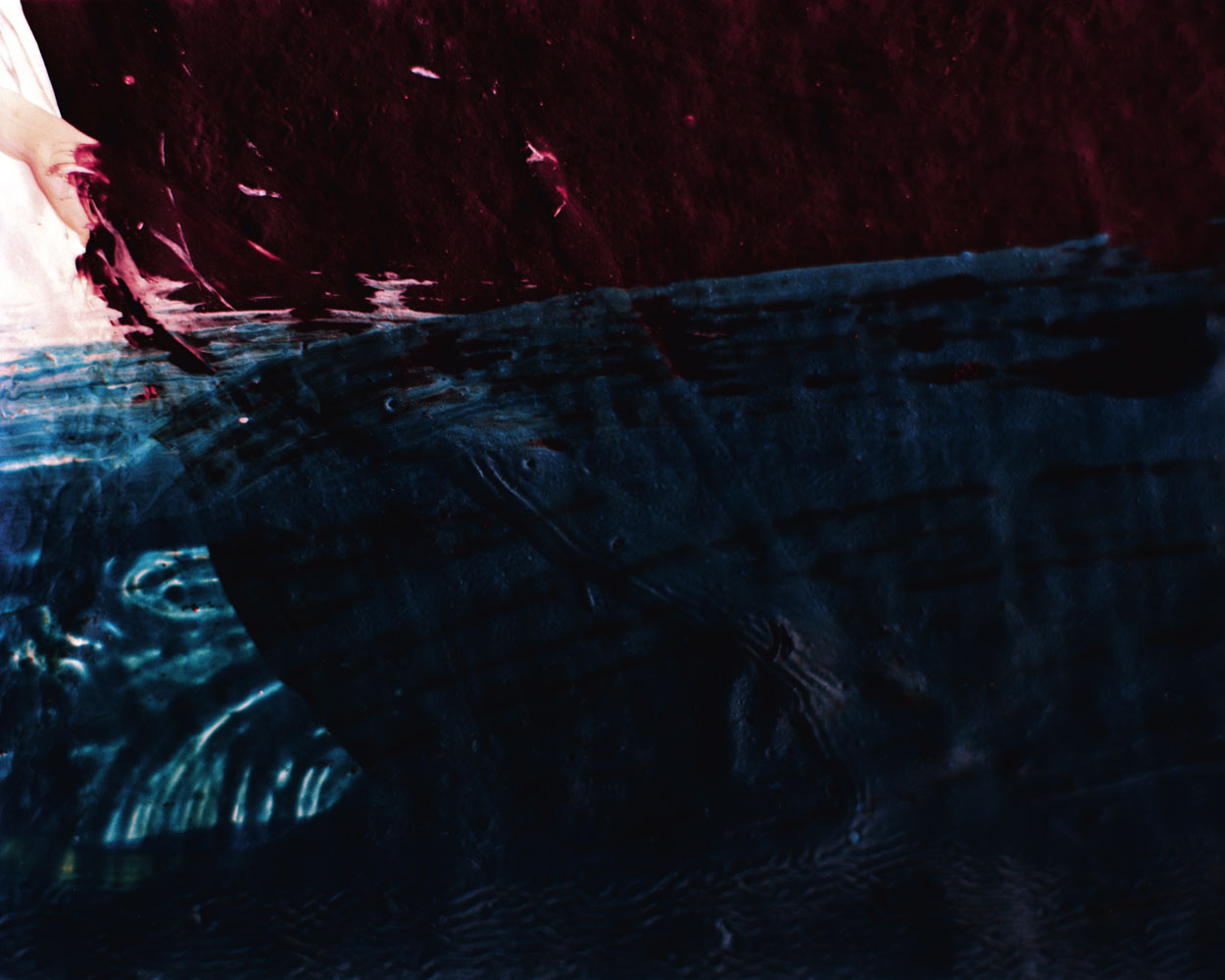

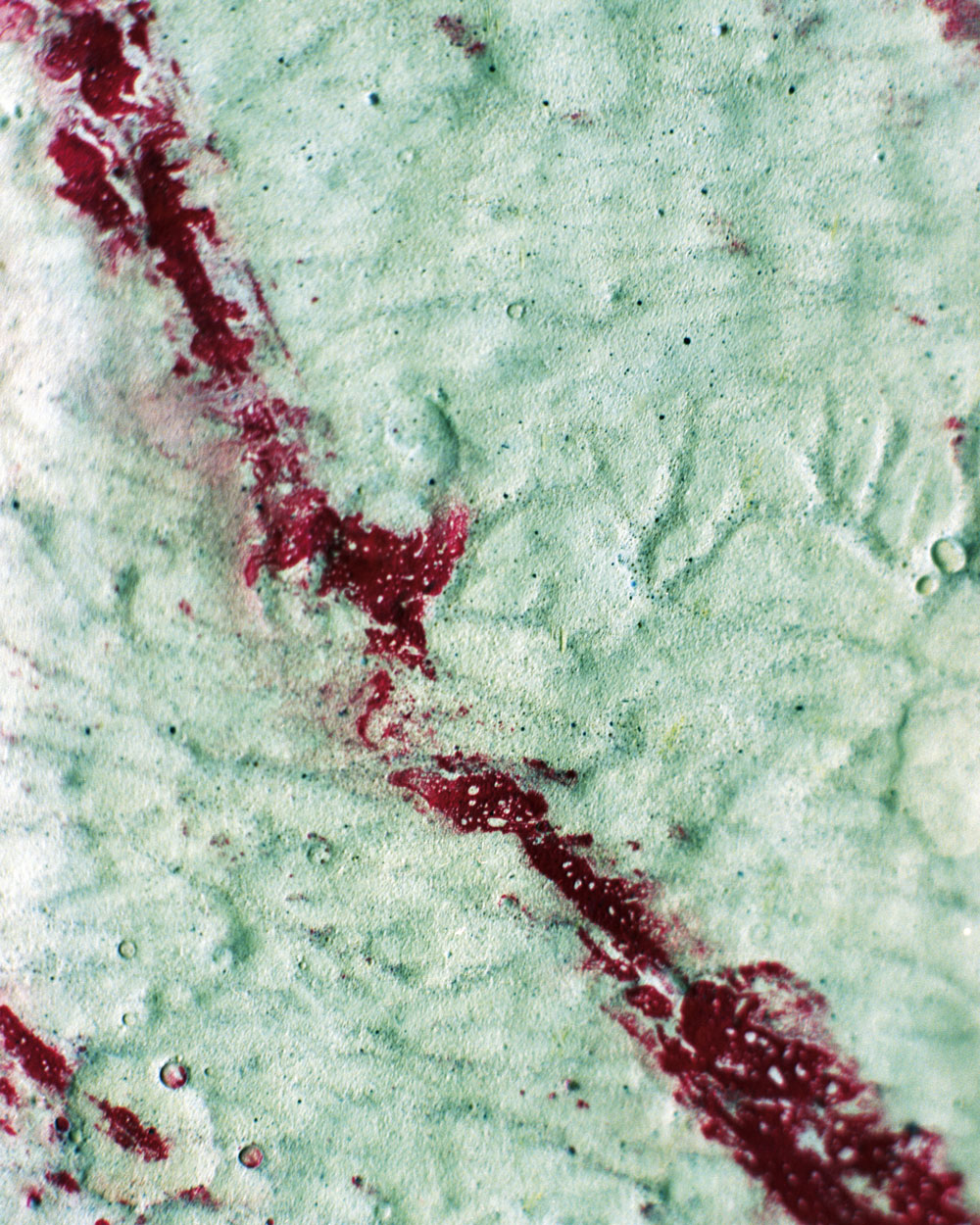

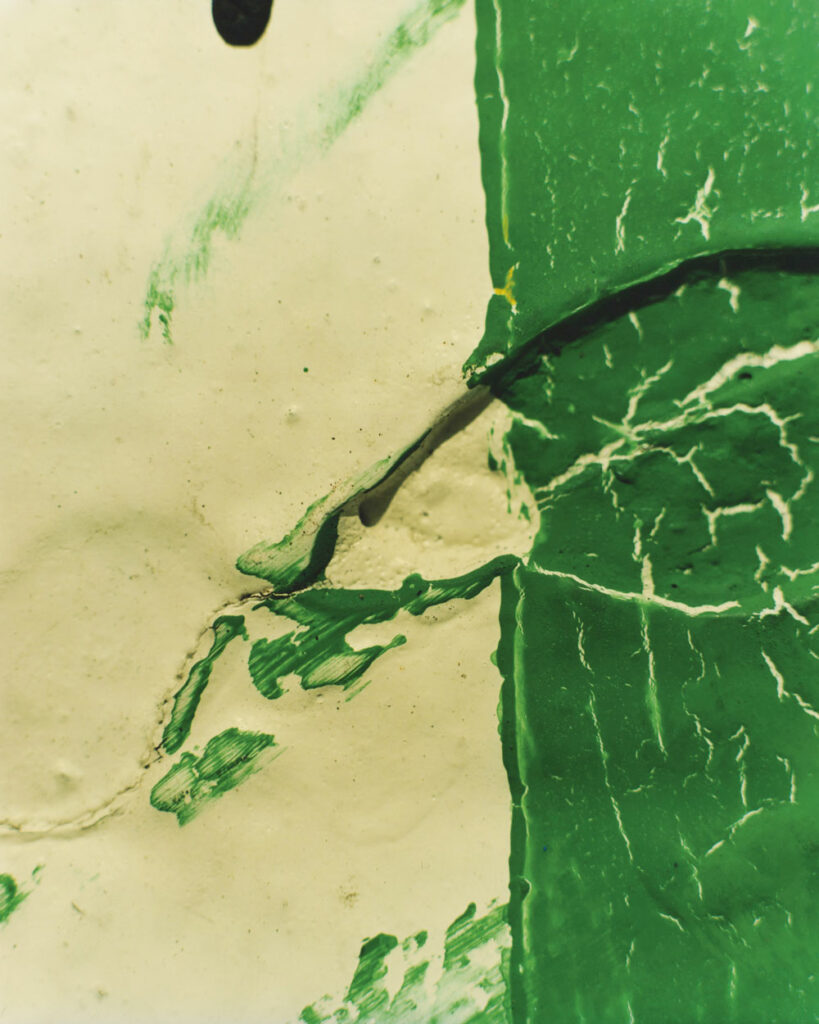

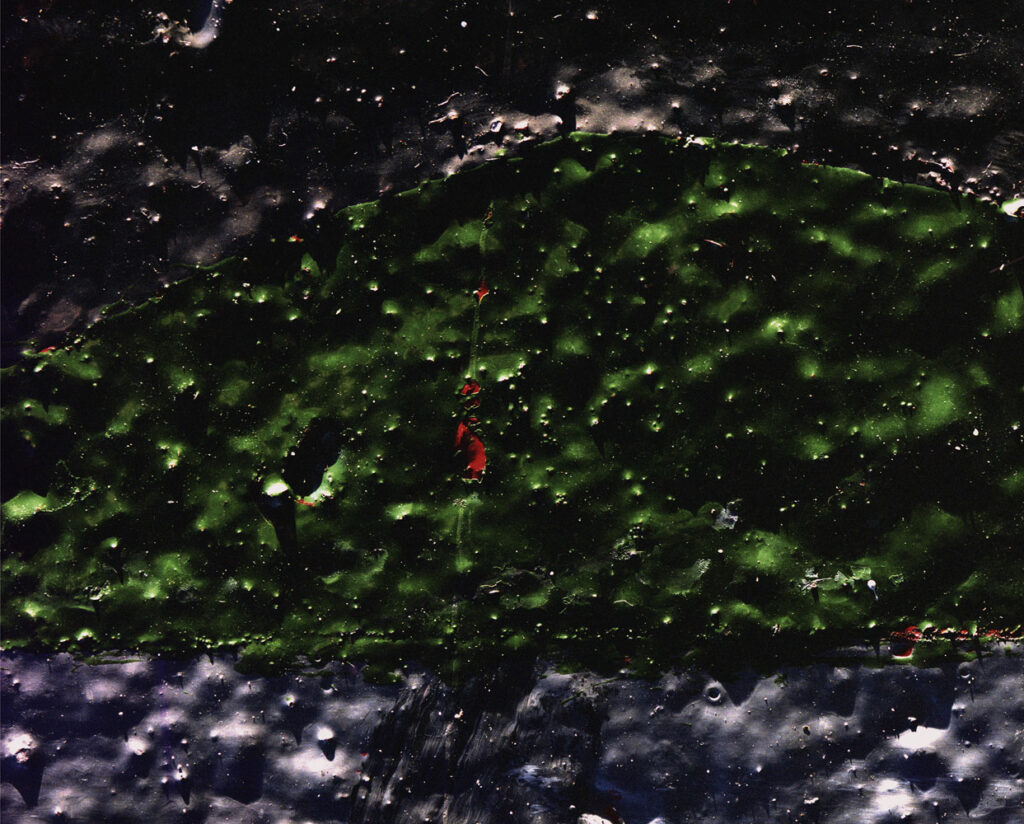

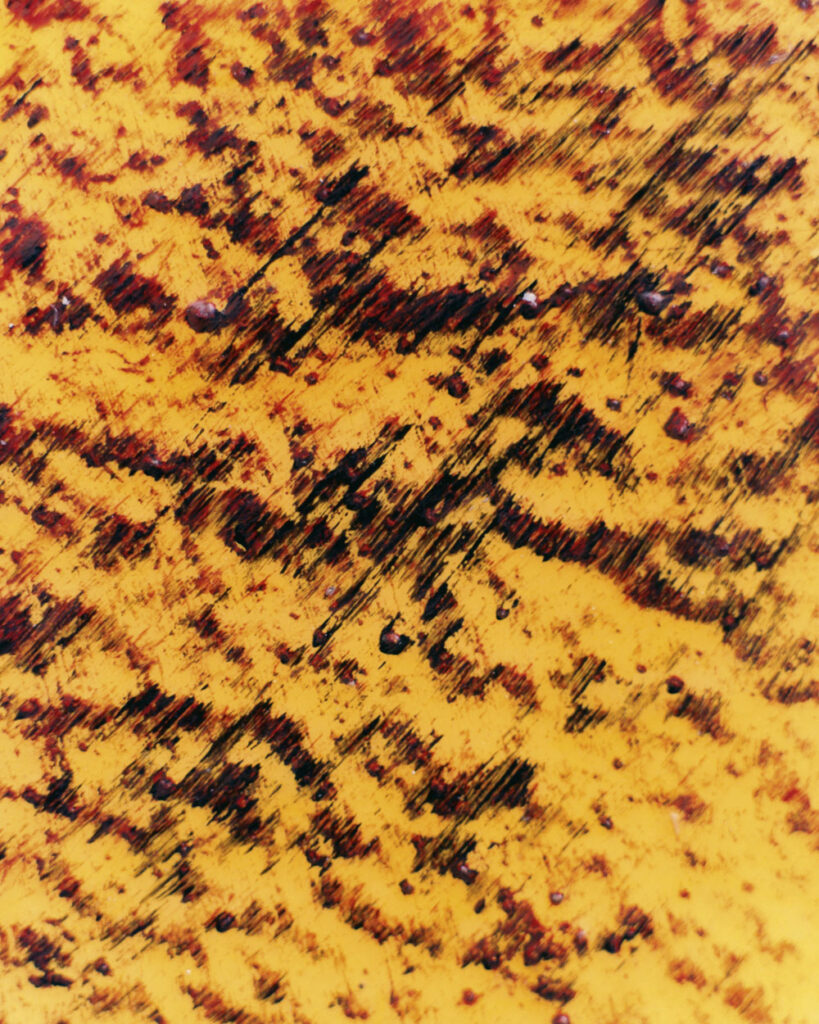

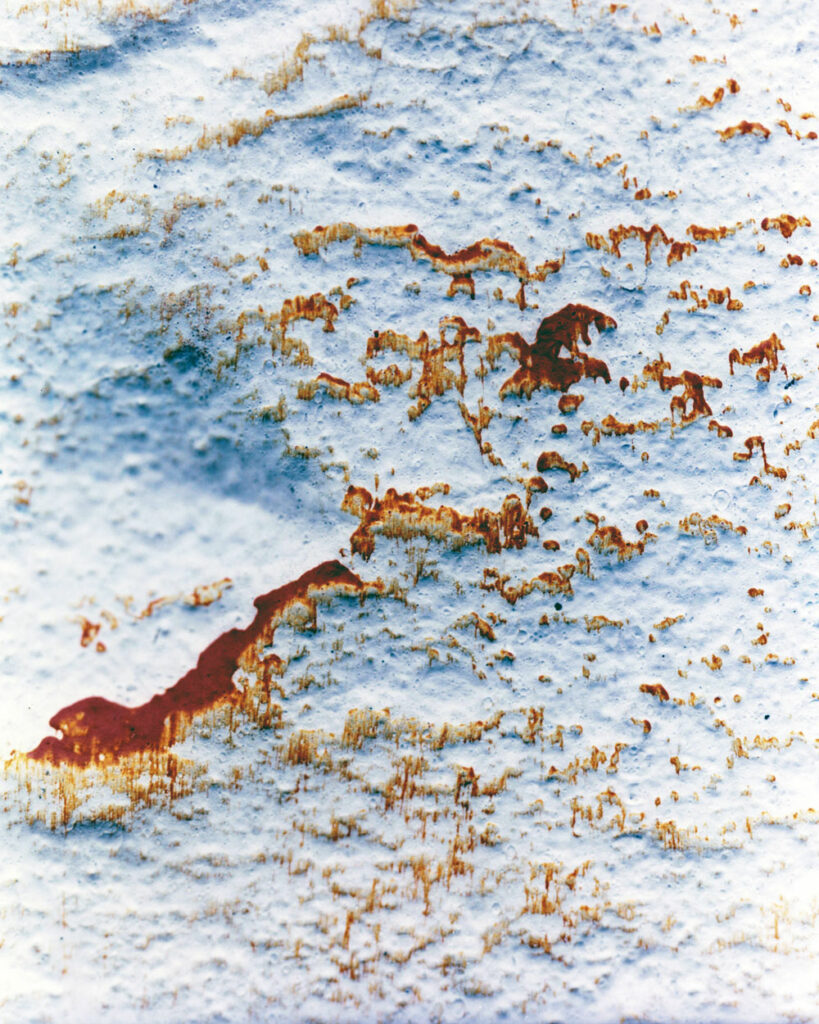

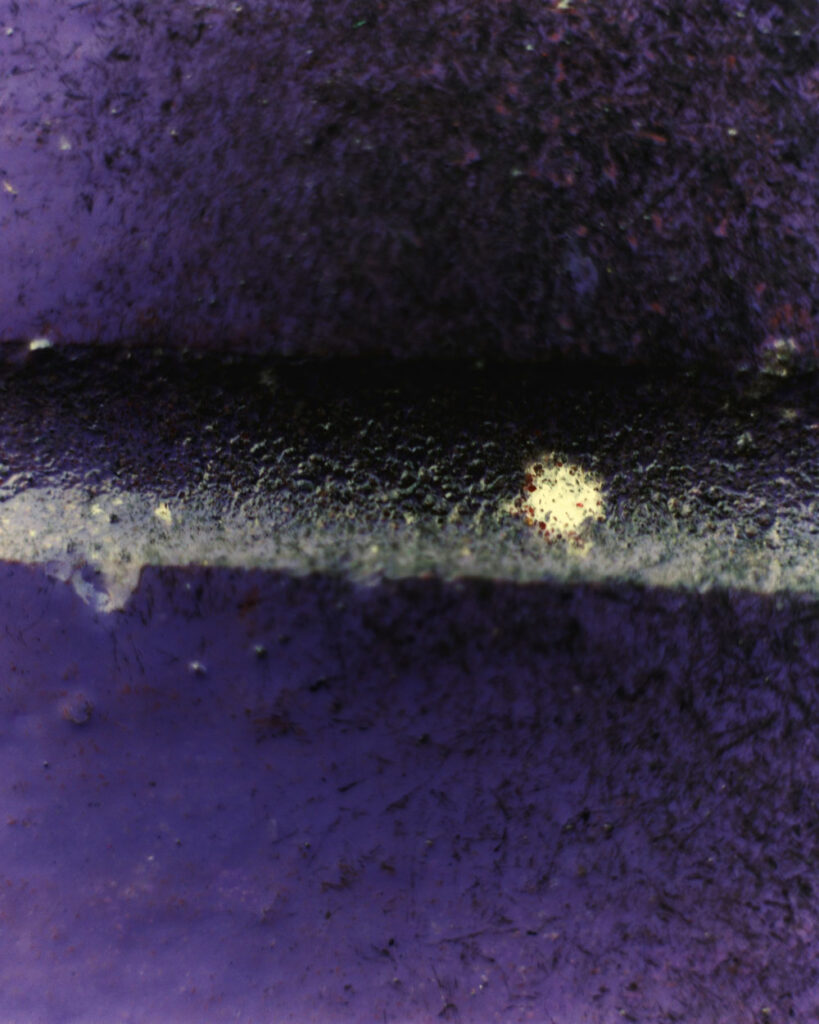

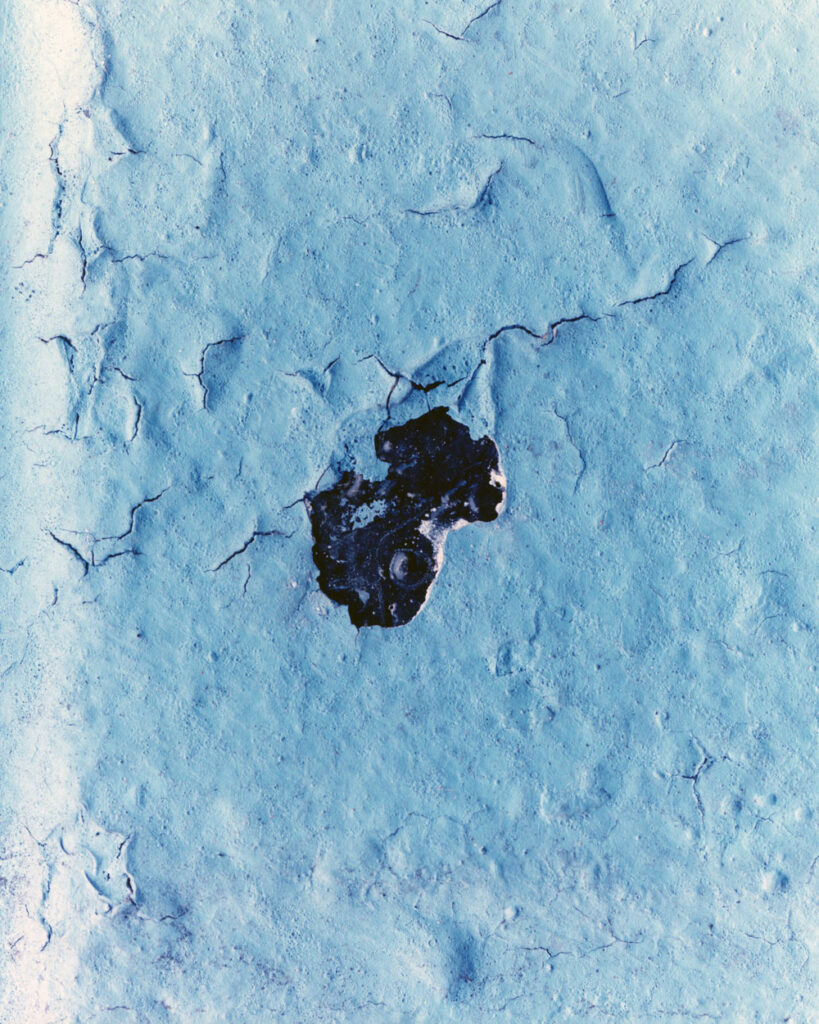

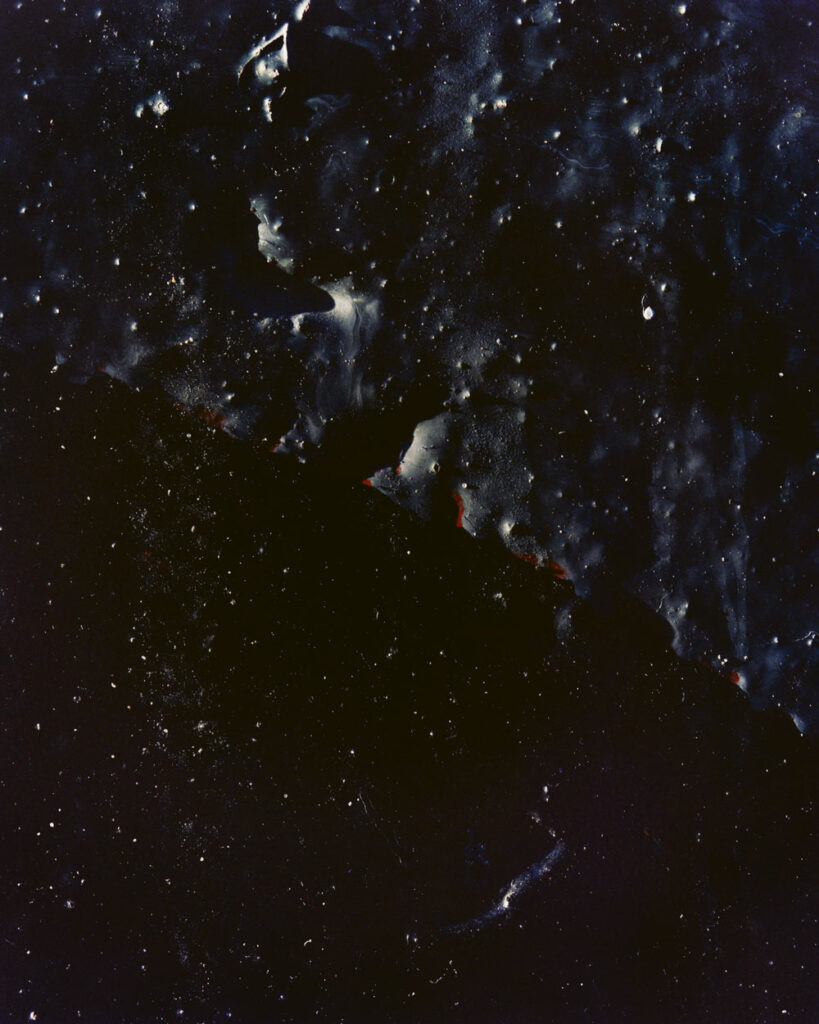

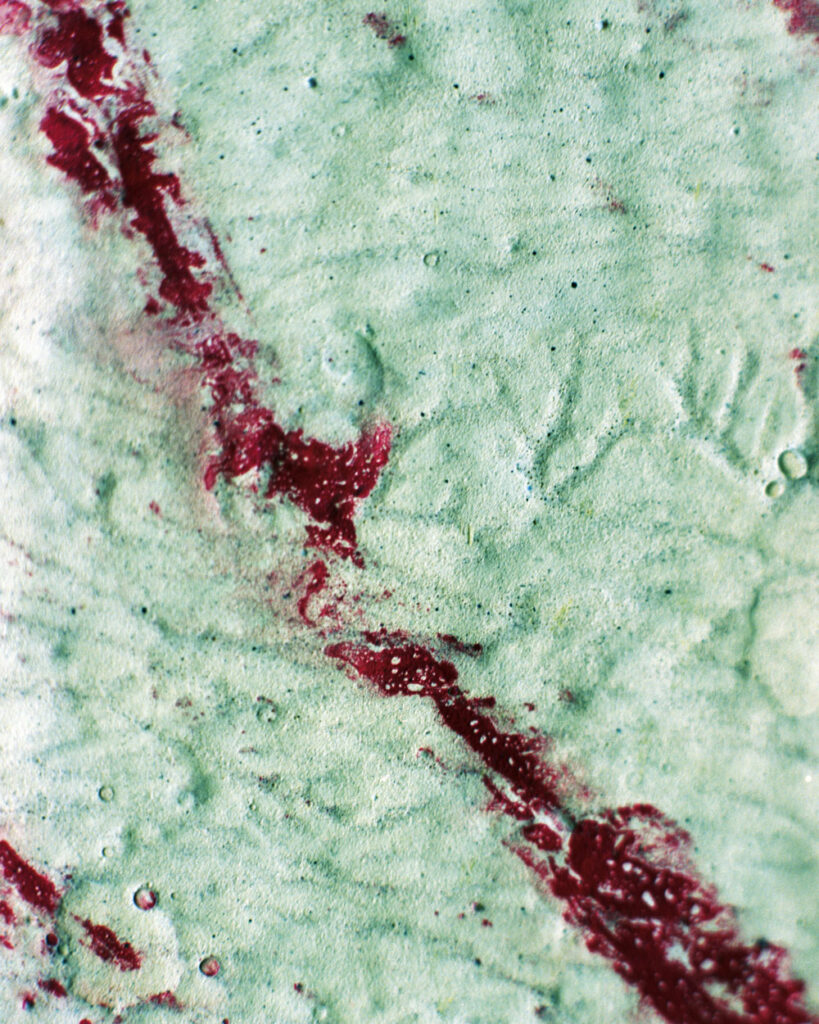

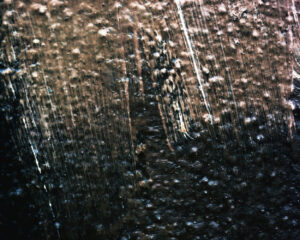

Murals are by nature ephemeral, subject to the deterioration of weather, to vandalism and graffiti, and, as is frequently the case in Northern Ireland, to over-painting and re-use. The chipped layers of paint seen in images like ‘Dark Days’ reveal the layers of history implicit in murals, which are rarely meant to be permanent and are repainted as political needs change. In ‘Dark Days’, flakes in a thickly-painted triangle of green reveal the red paint underneath; like blood it seeps to the surface, unable to be fully covered or erased. Earlier murals are added to and painted over creating thick layers of paint on the rough walls. McConnell’s stress on the objecthood of murals reveals the ways in which they are “used and abused, admired and transformed, replaced and defaced,” as dynamic and changeable mechanisms for the construction of communal identity.

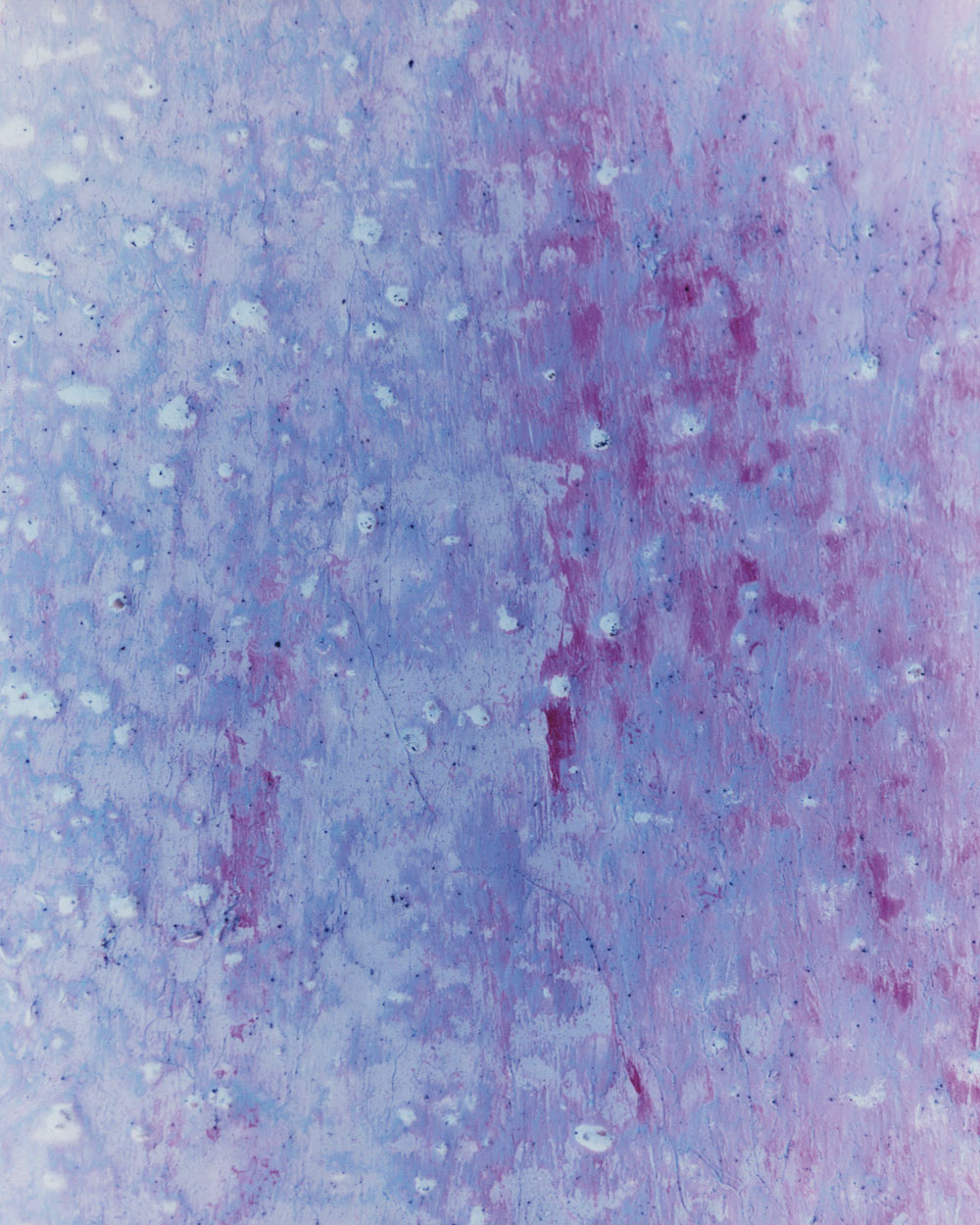

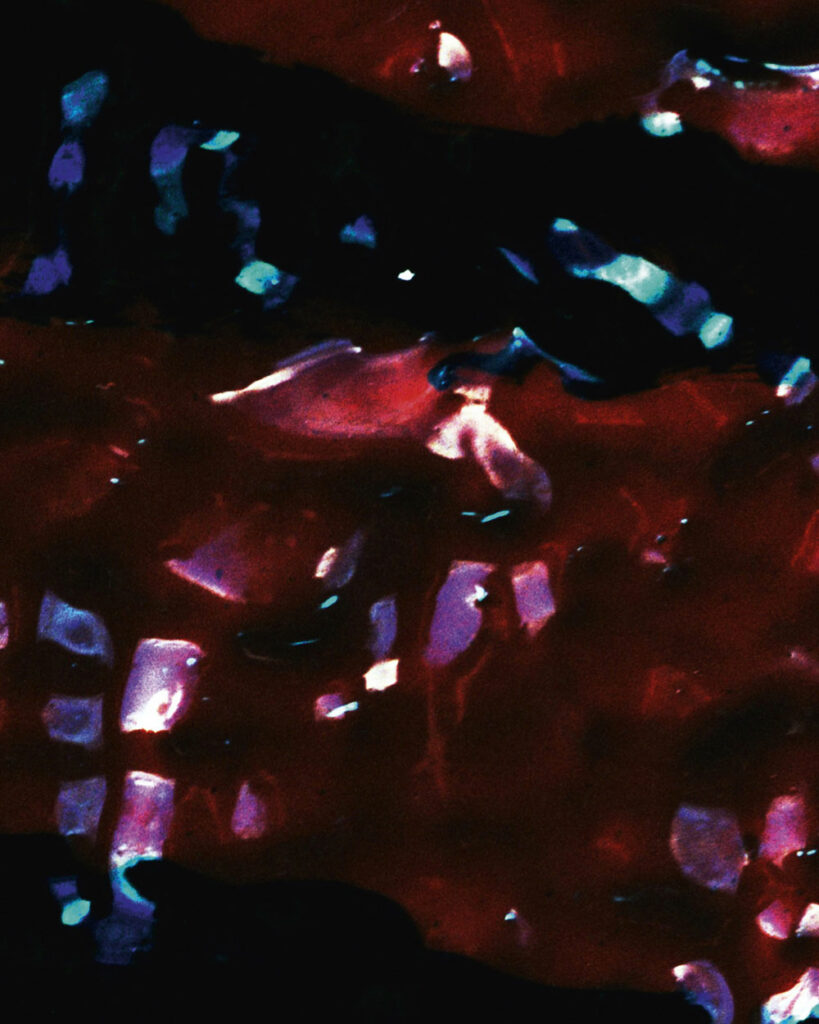

By emphasizing the physicality of the murals, McConnell not only highlights their method of production but also removes them from their cultural context. Without any representational imagery, the works are unidentifiable as political; the role of the murals in context is predicated upon the instantly recognizable imagery of a particular cause or group. When abstracted, the murals are reduced to little more than their component parts, stripped of meaning and therefore of purpose. While in situ, murals act as delineations between spaces, identifying areas as belonging to and protected by certain groups, the removal of place, context and meaning breaks down boundaries between spaces and political affiliations. His photographs are visual markers without meaning. His work brings to mind the ways in which similar or even identical symbols, myths, and figures are imbued with different significance in the service of each tradition. For example, murals in support of both nationalist and unionist politics employ the figure of Cuchulainn as alternately the hero of Ireland and the defender of Ulster.

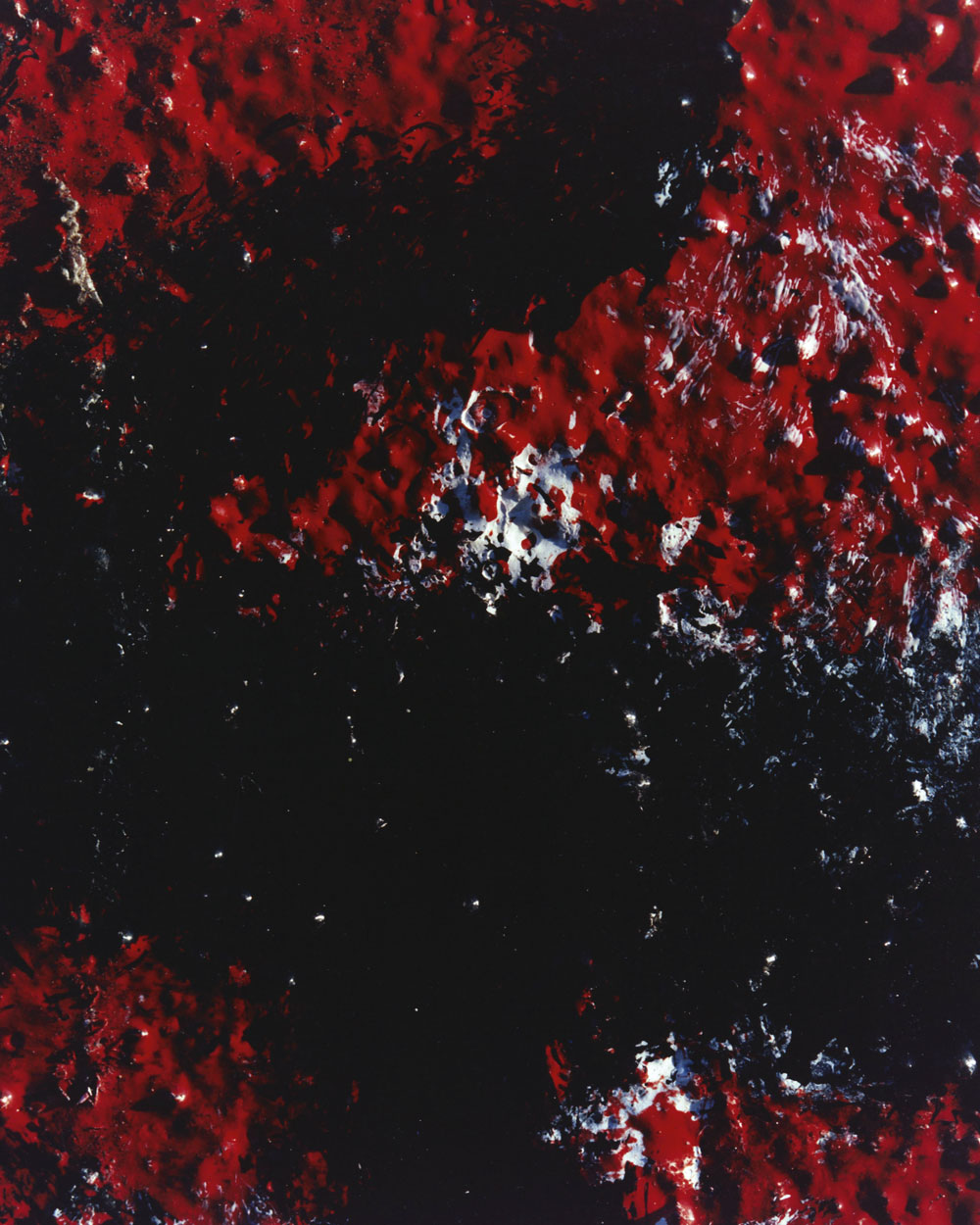

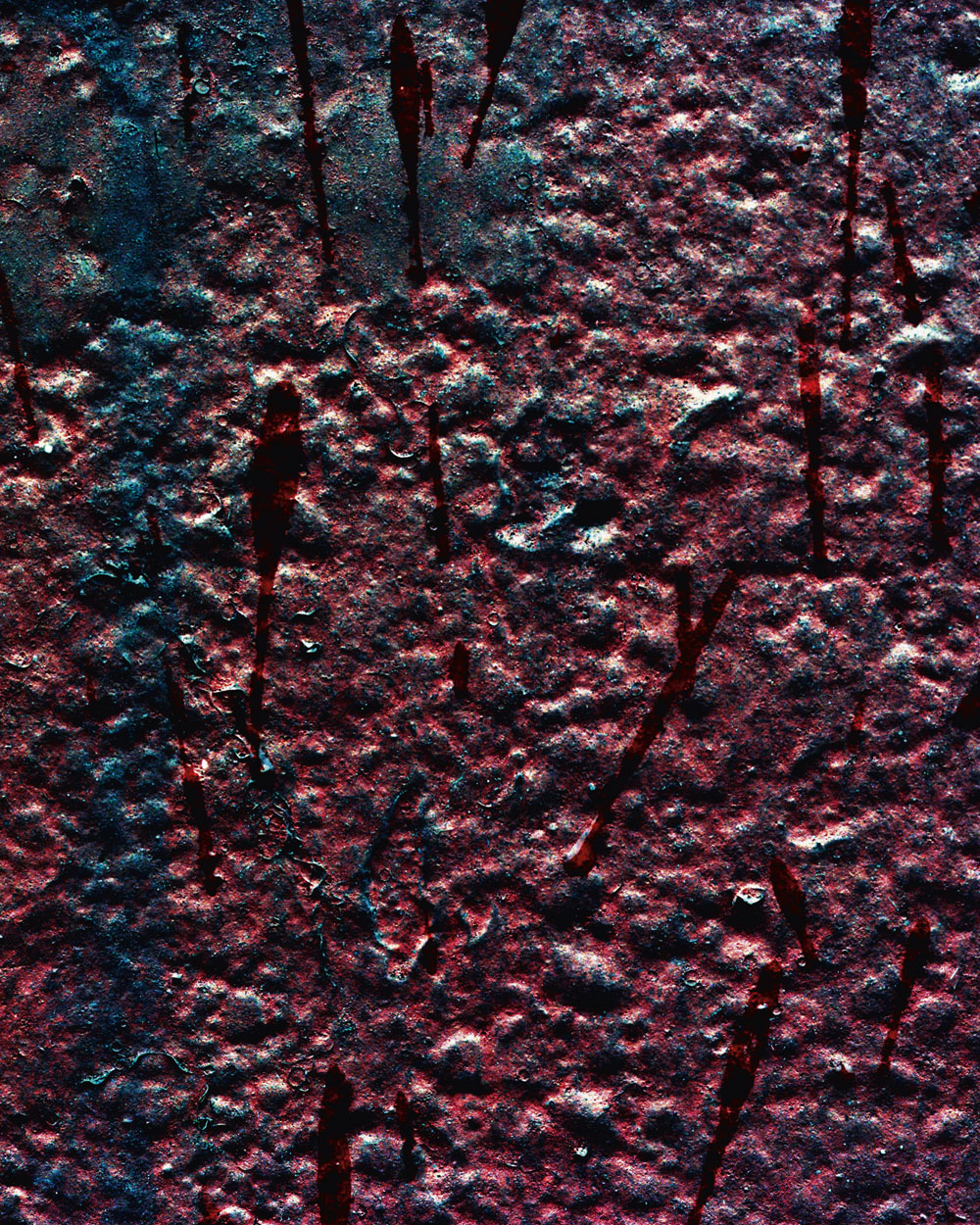

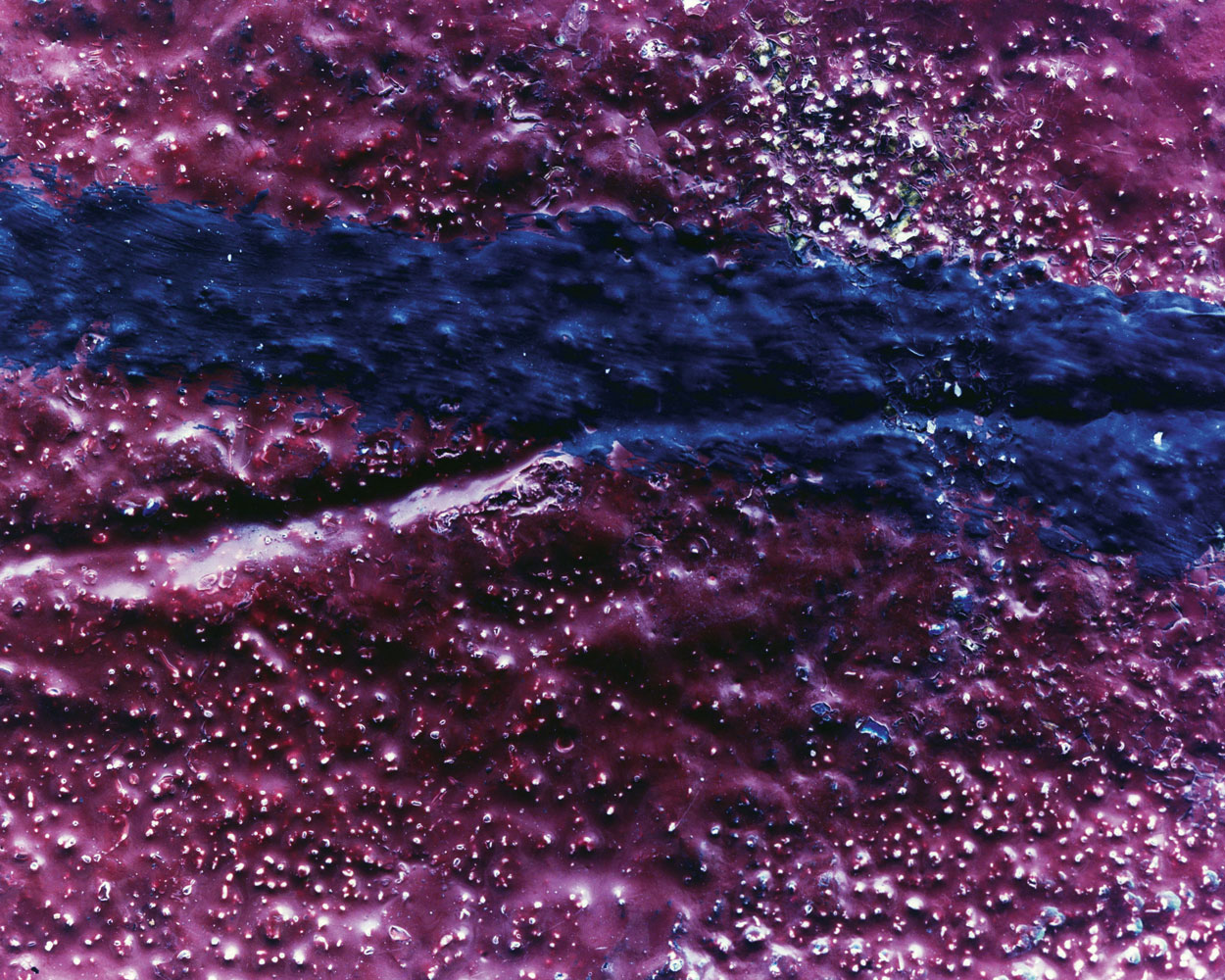

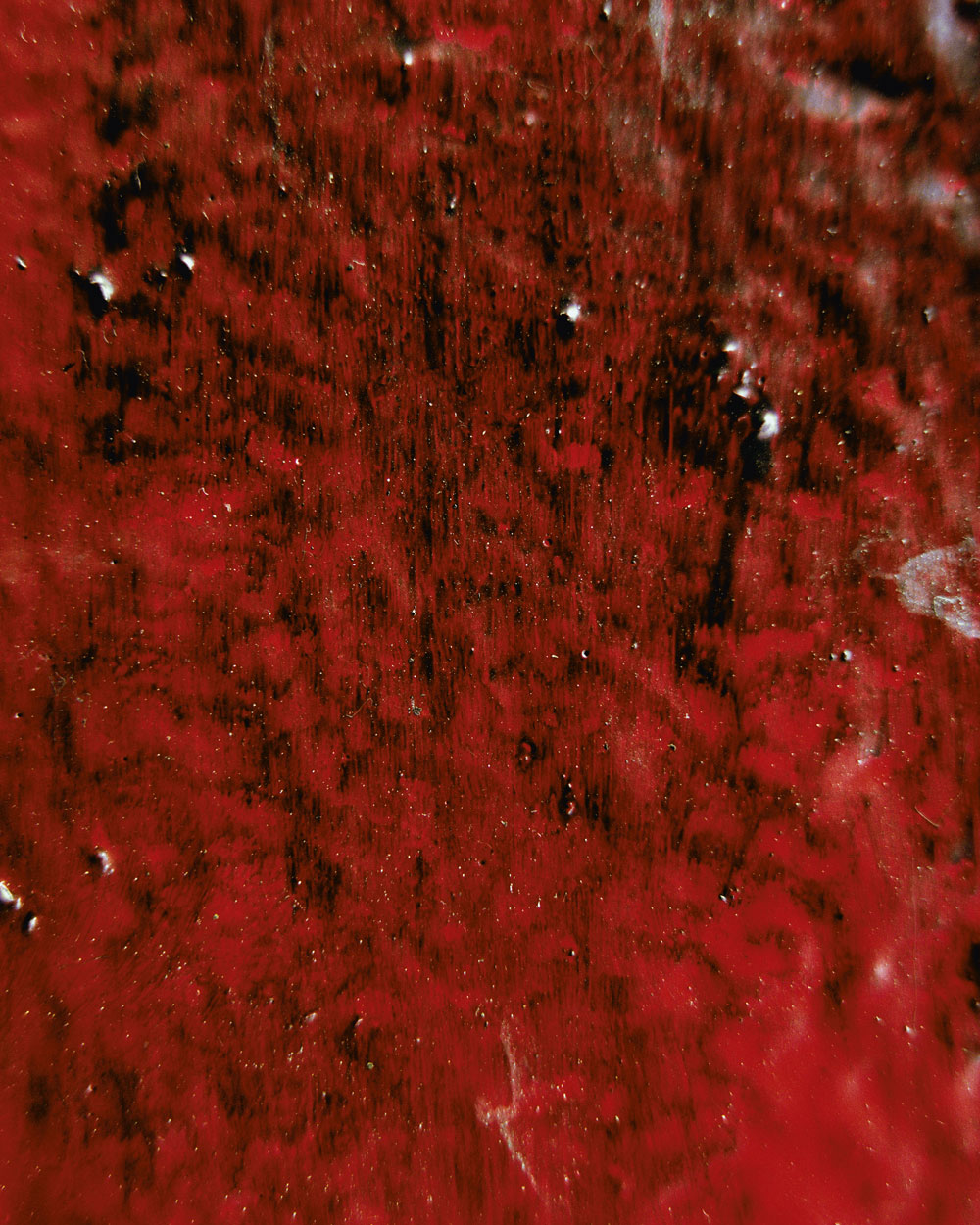

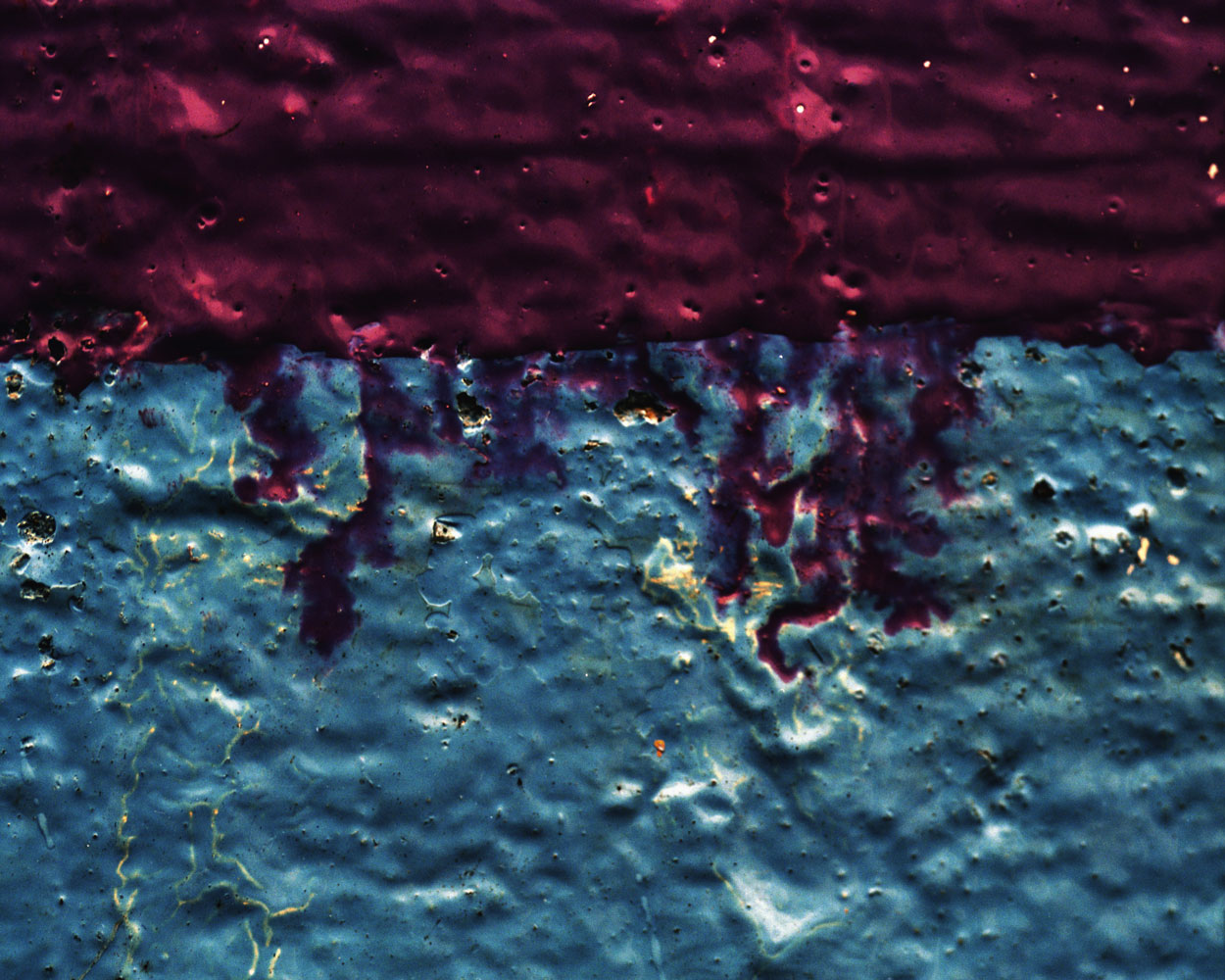

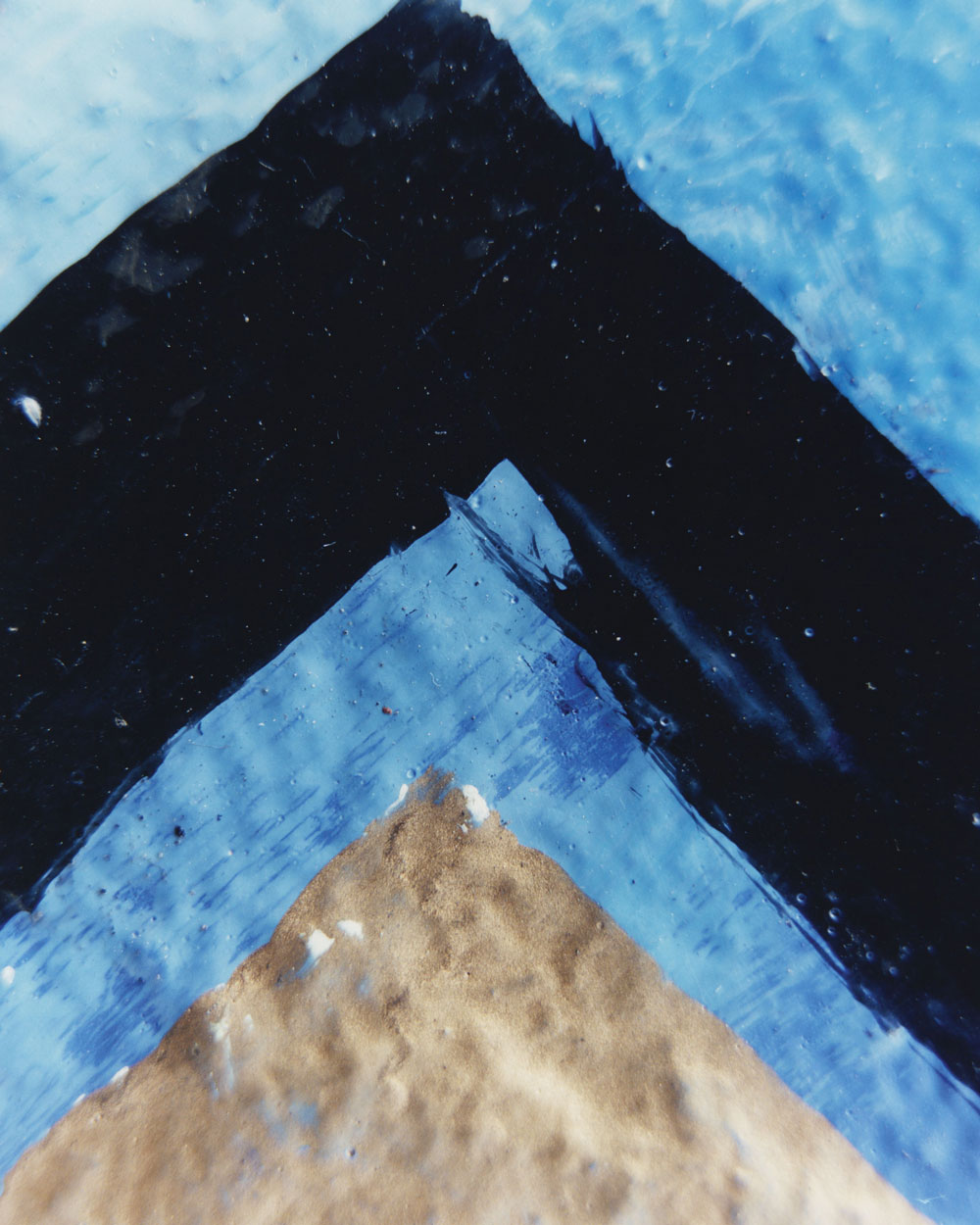

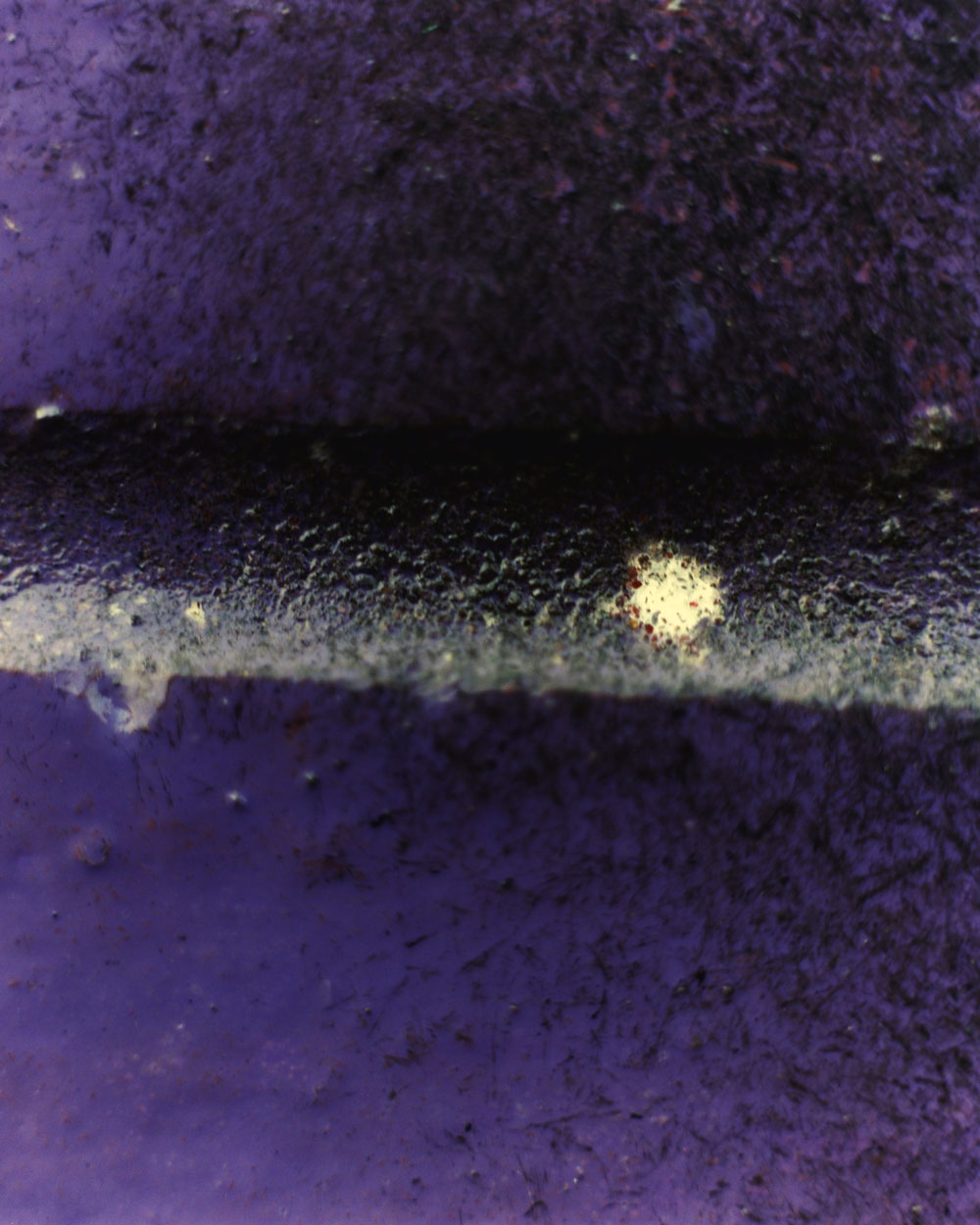

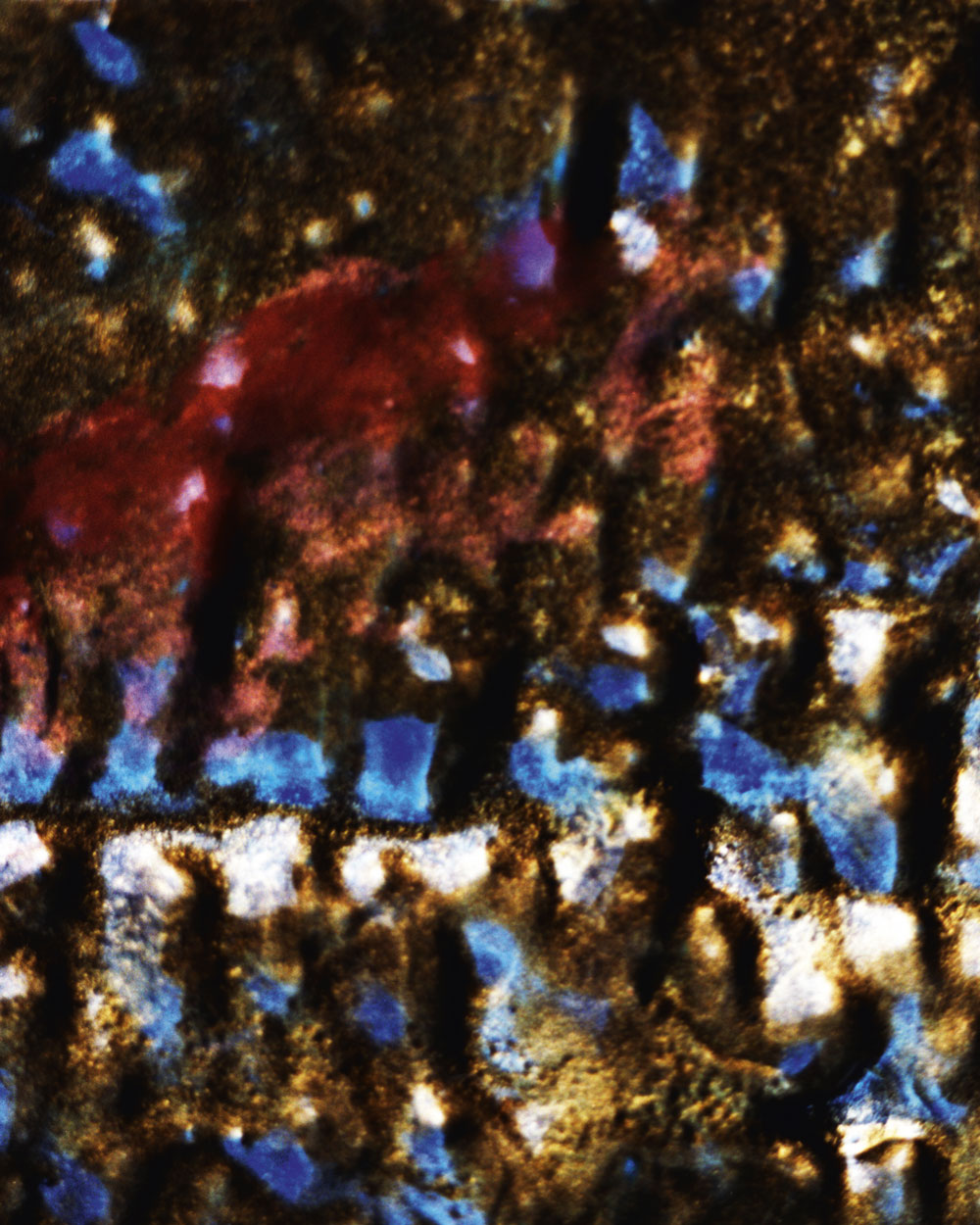

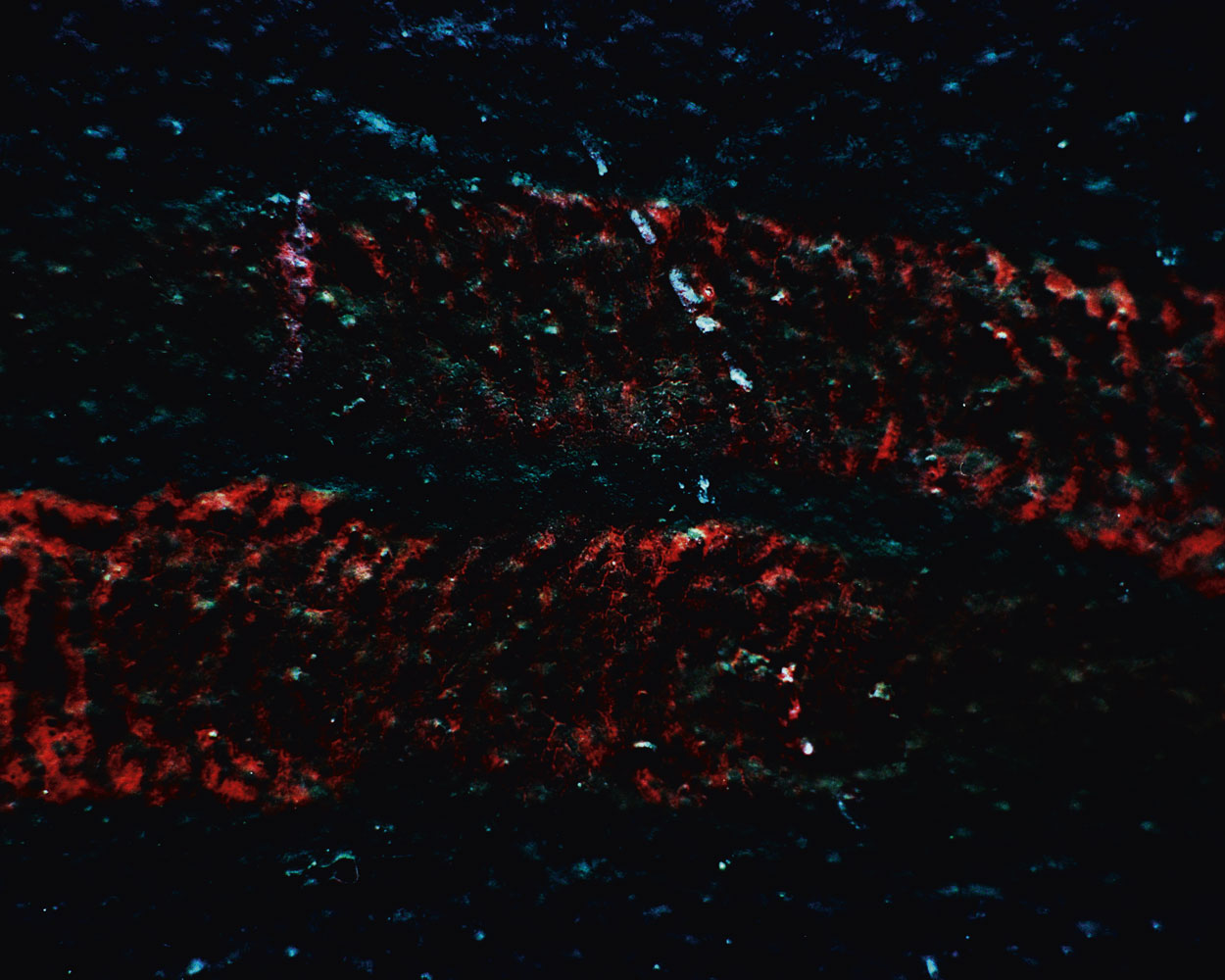

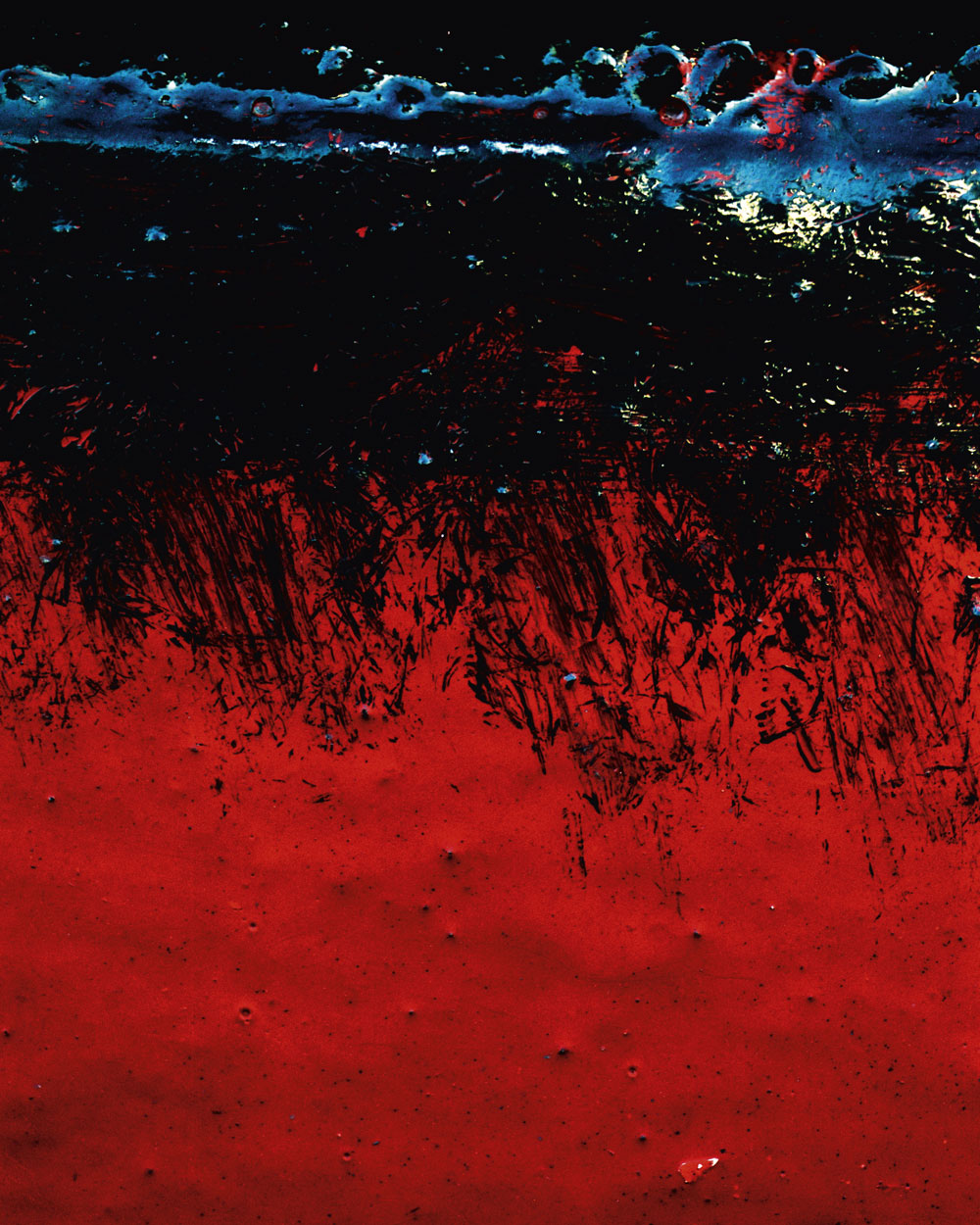

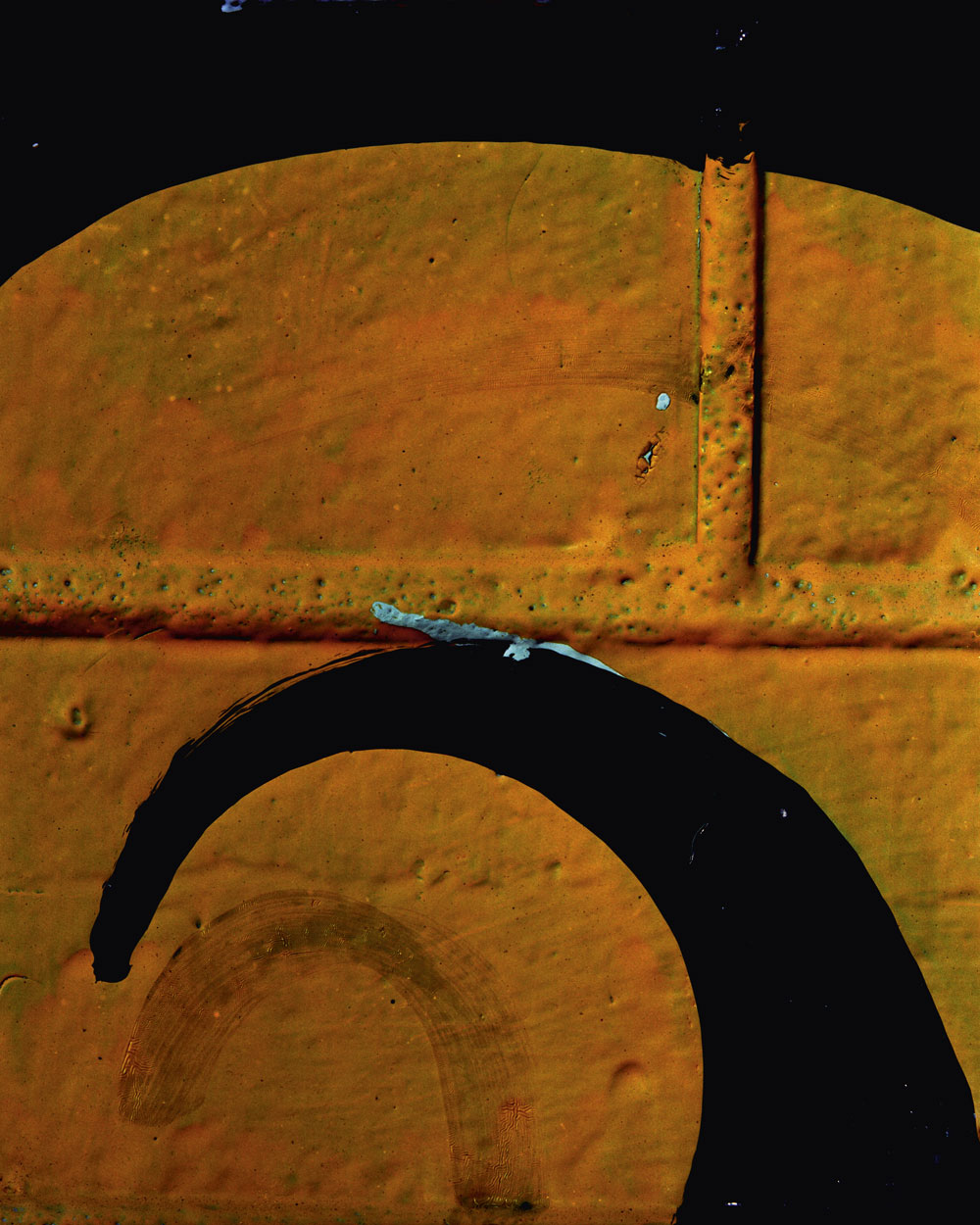

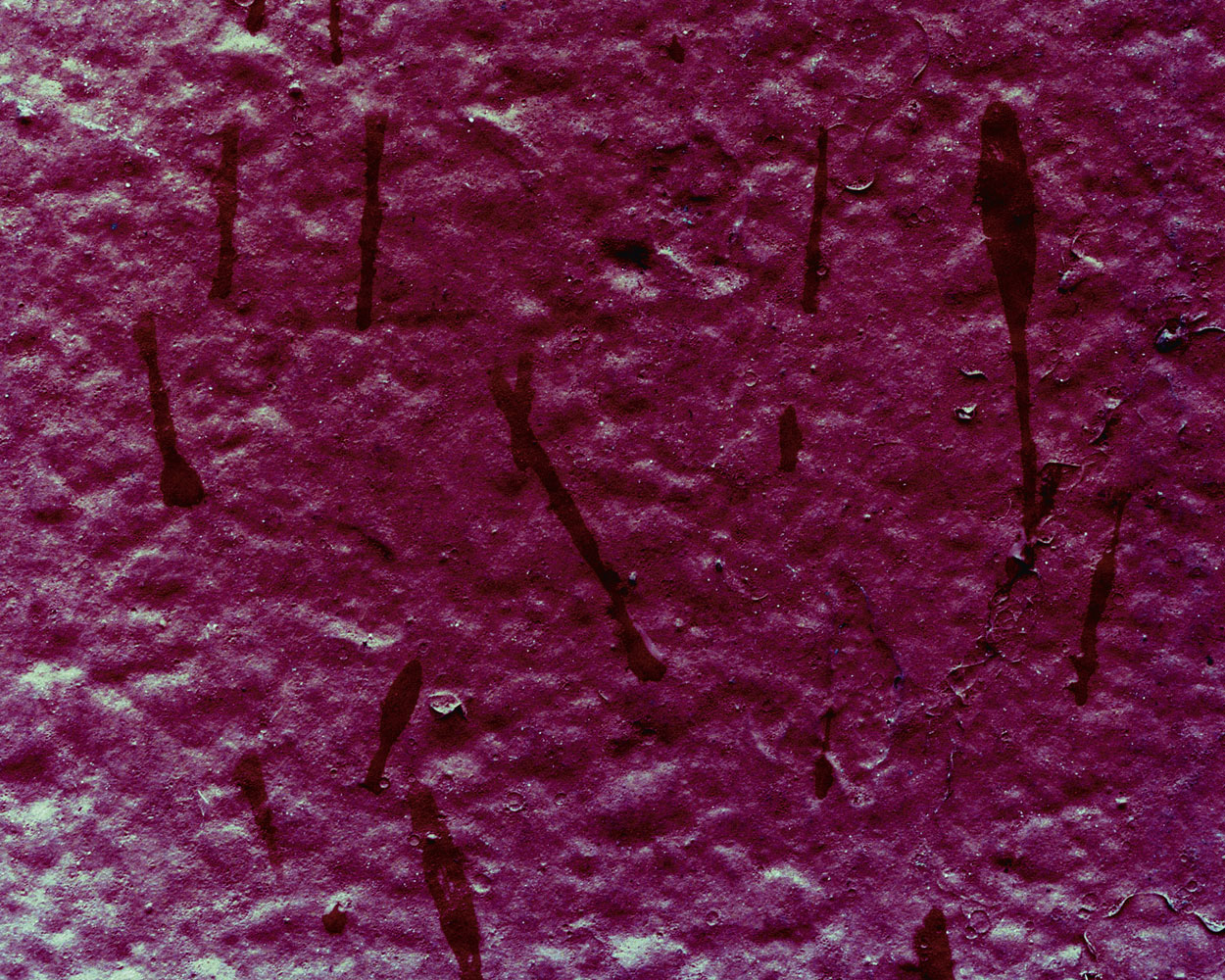

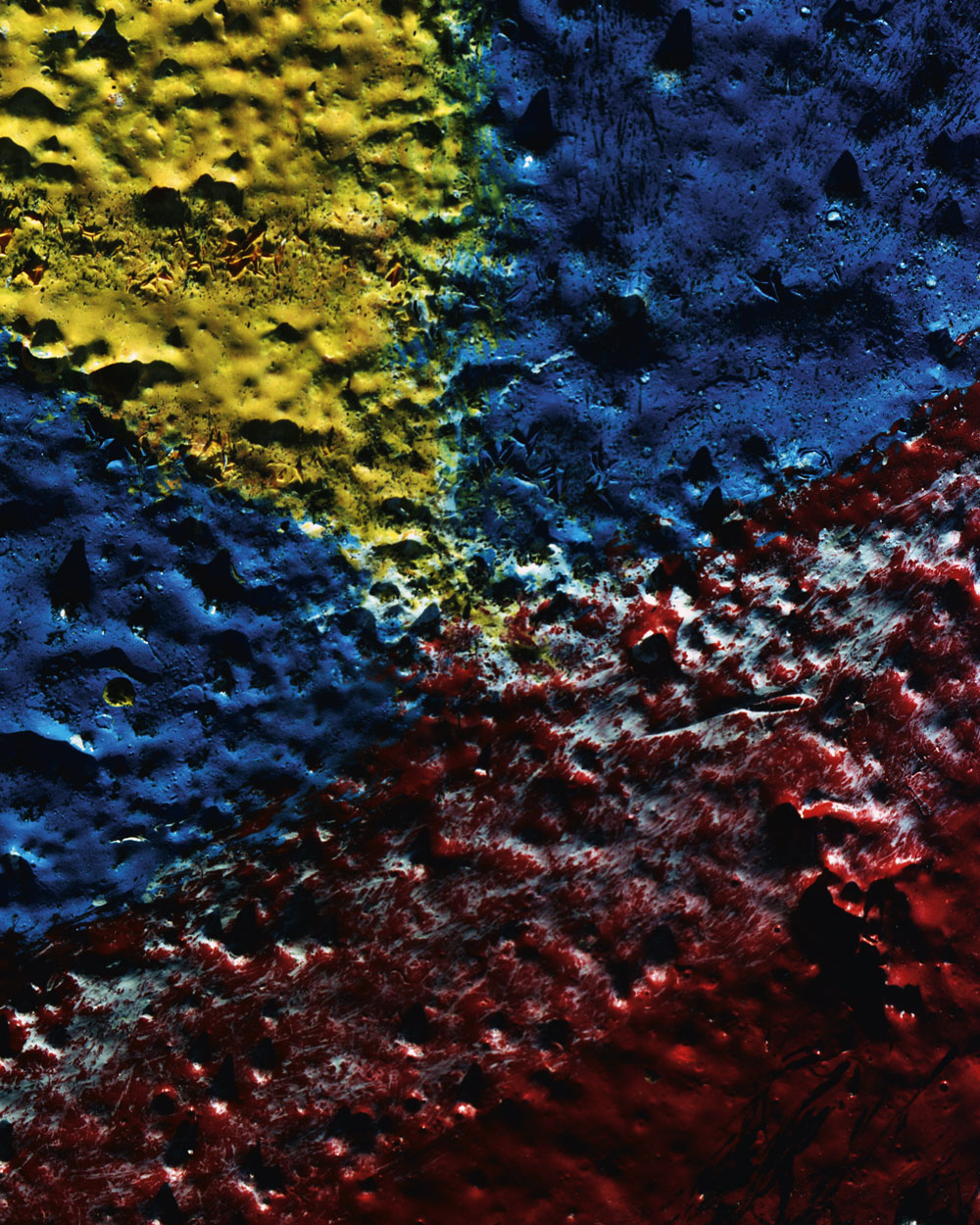

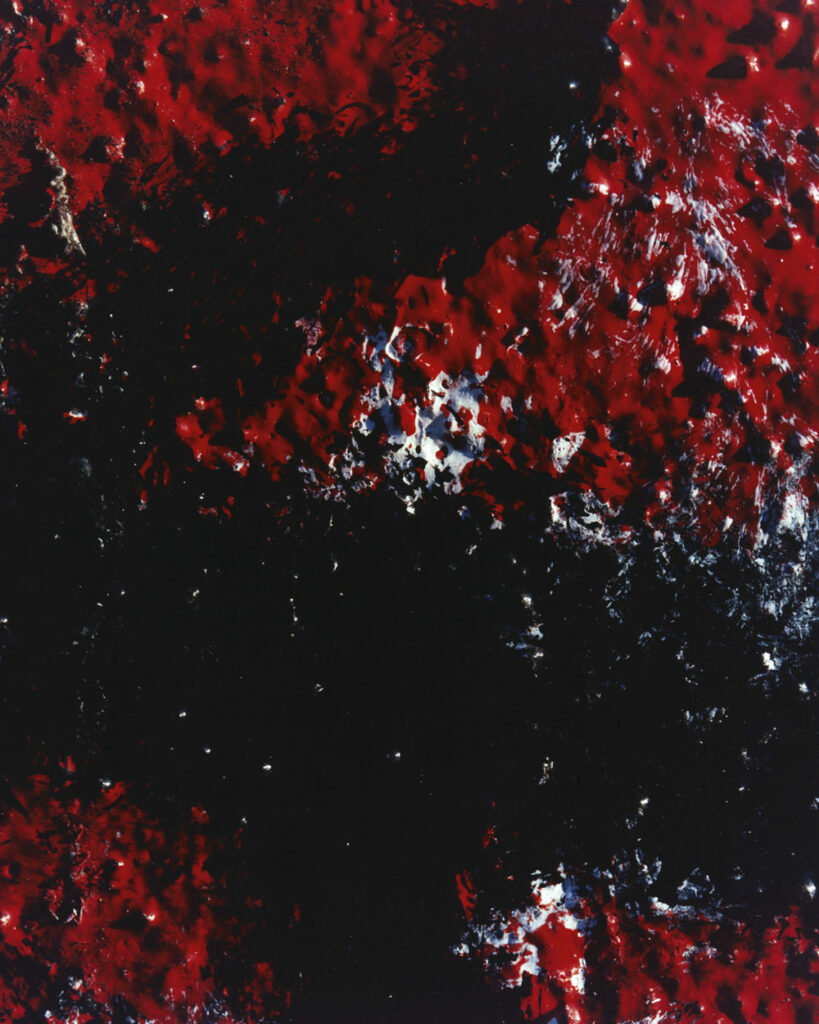

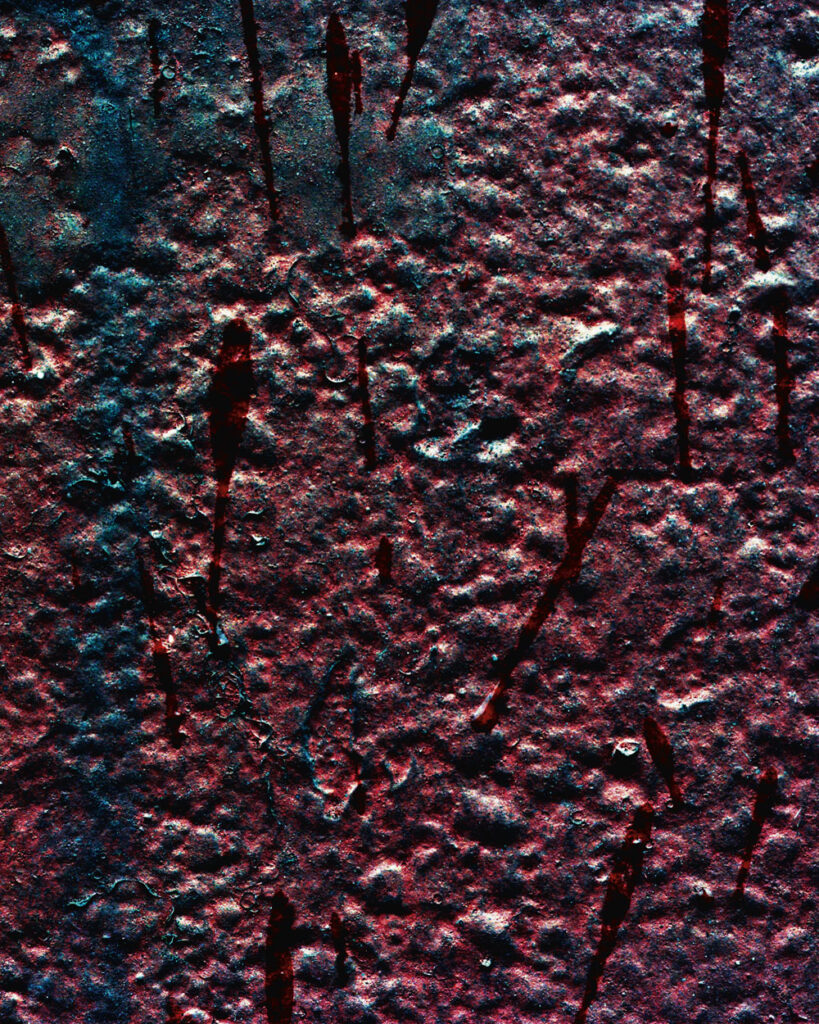

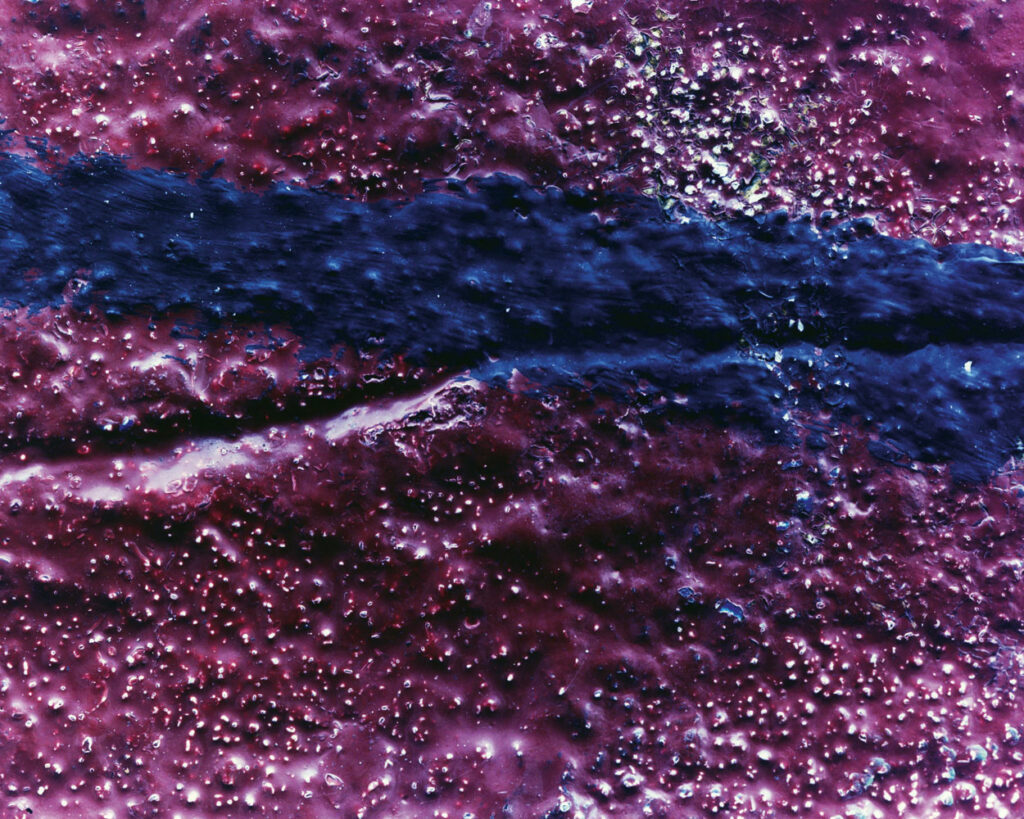

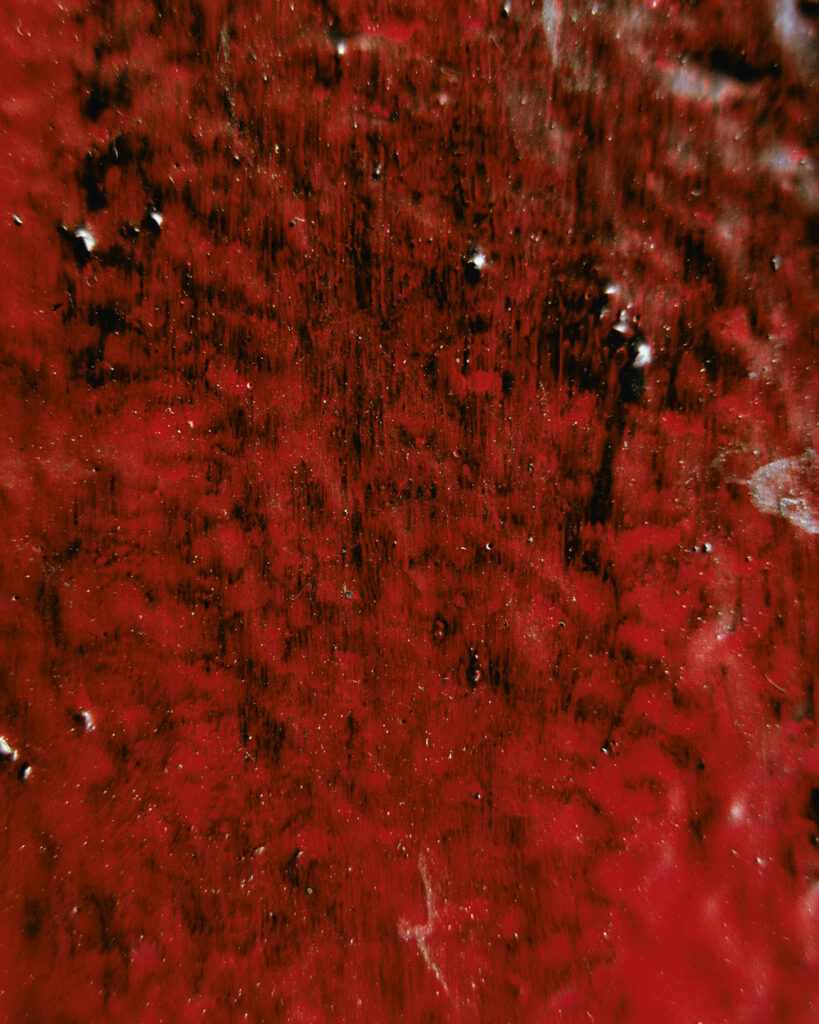

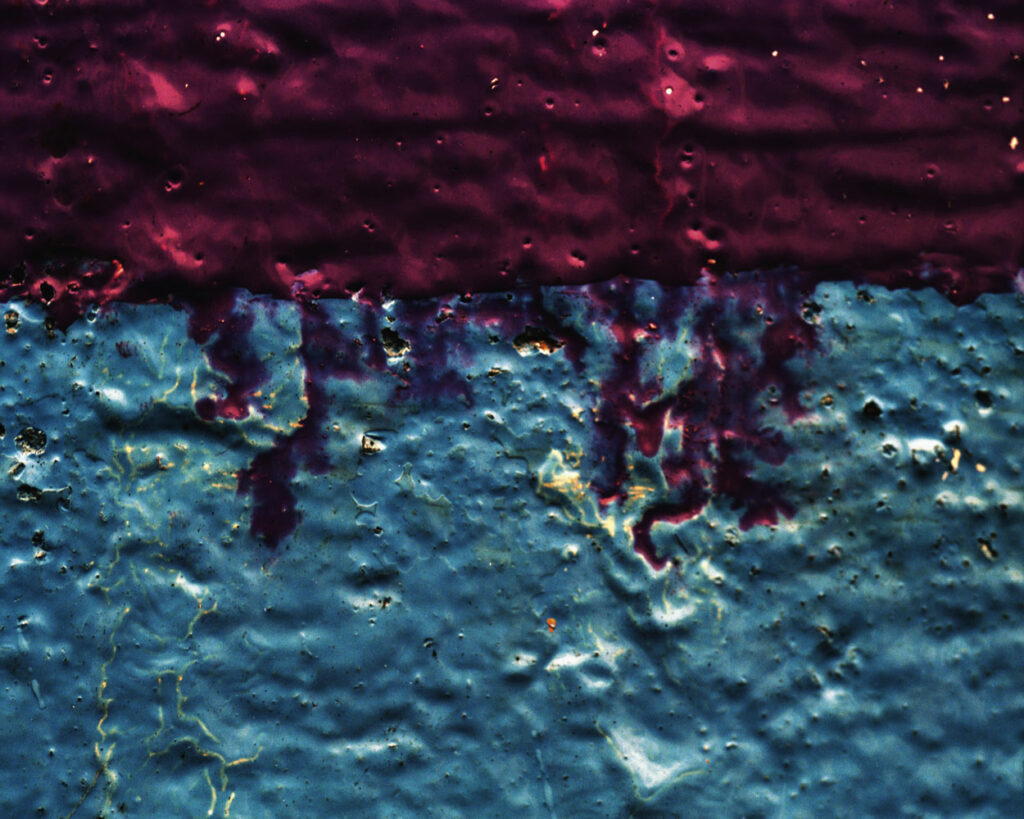

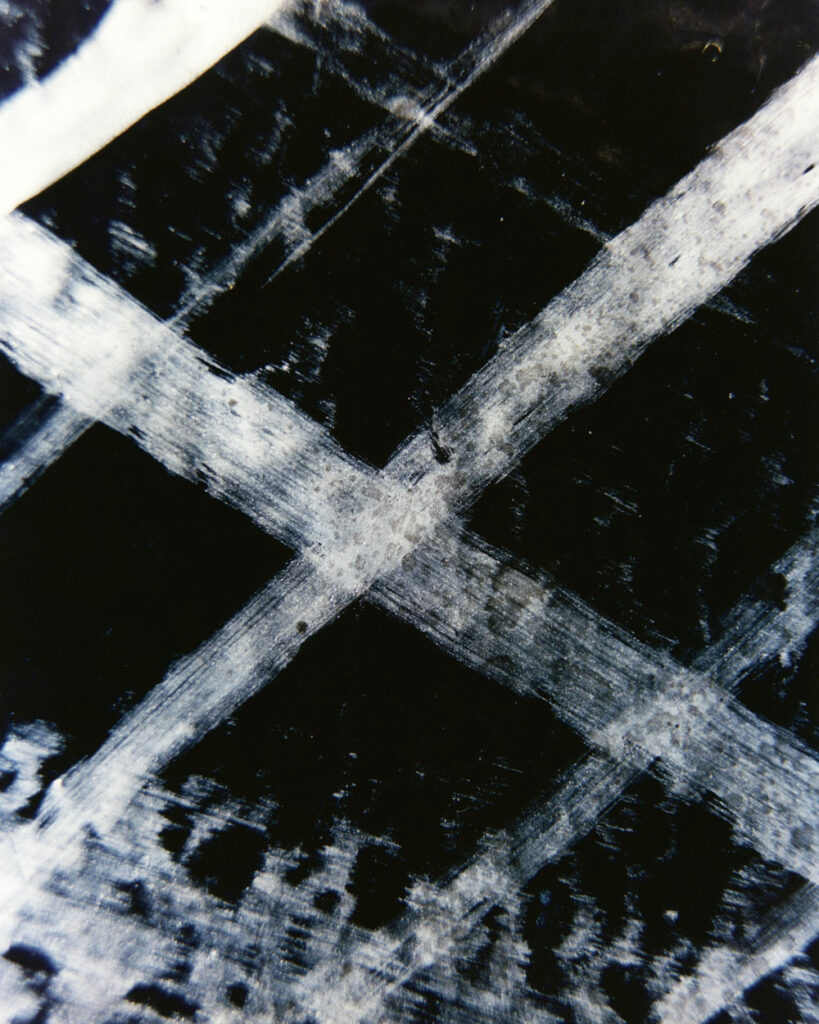

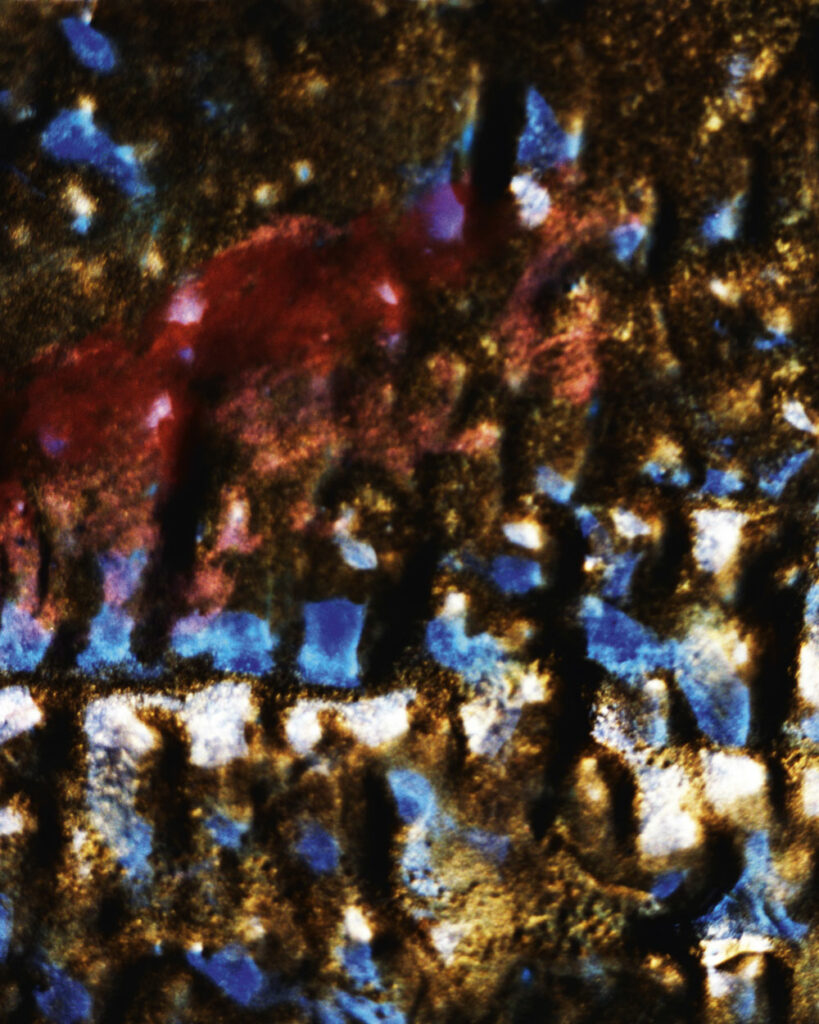

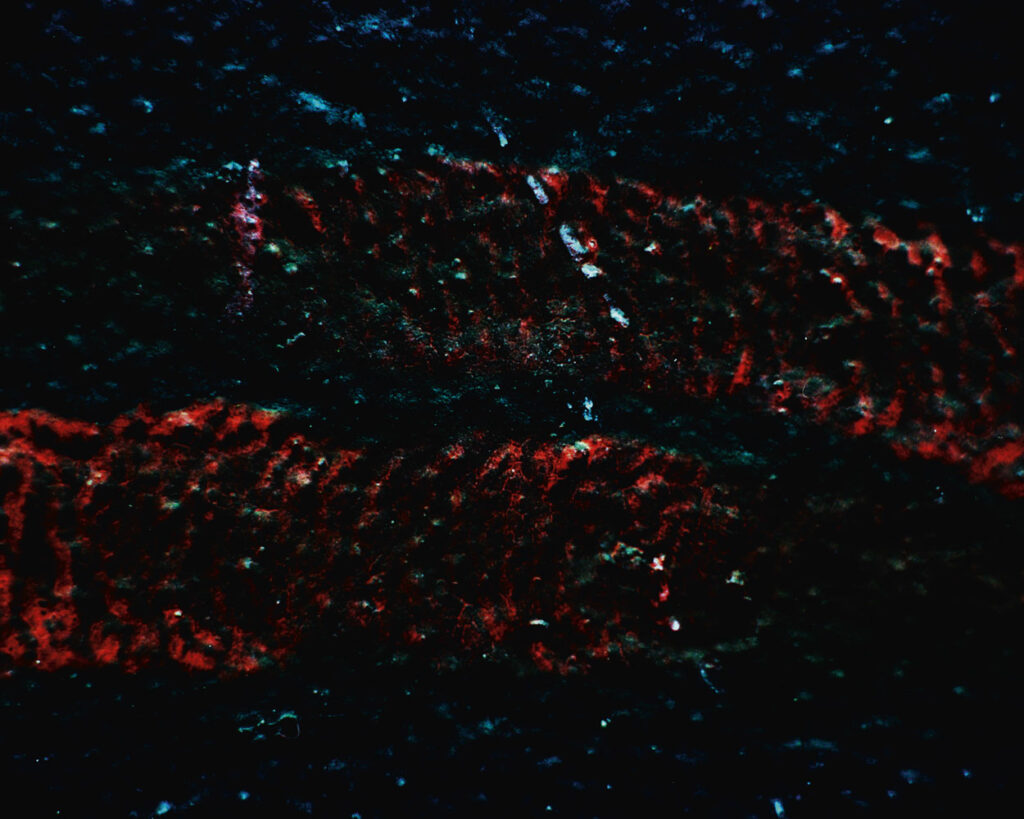

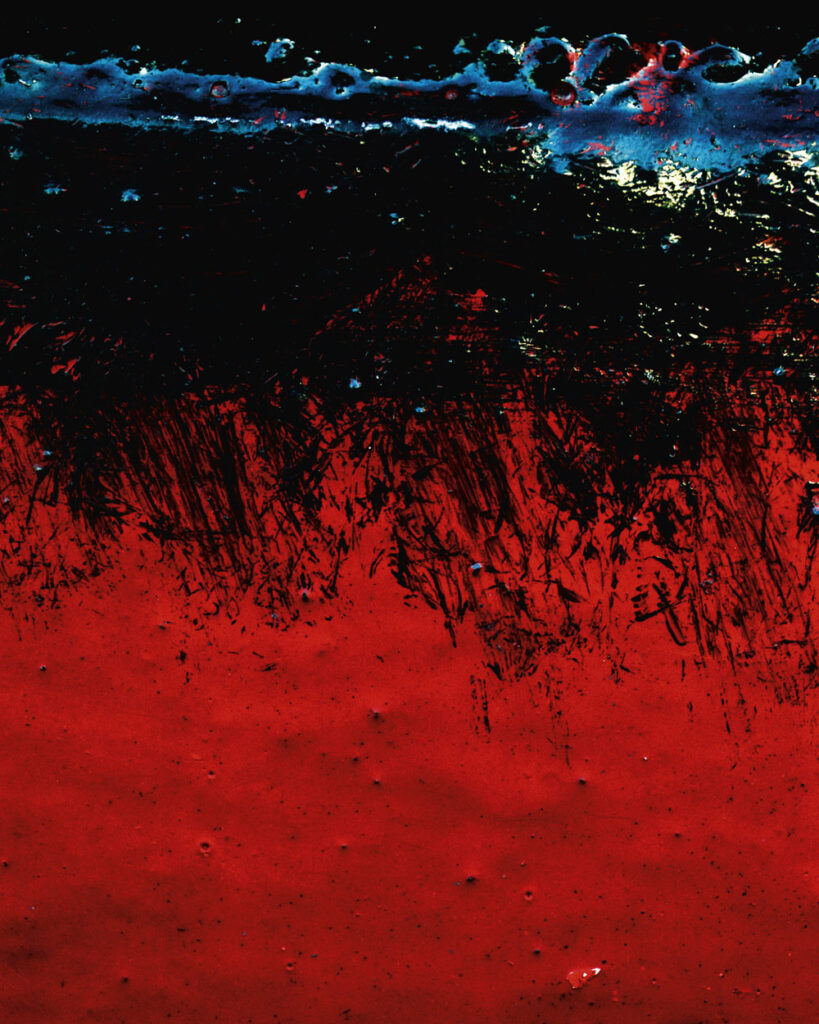

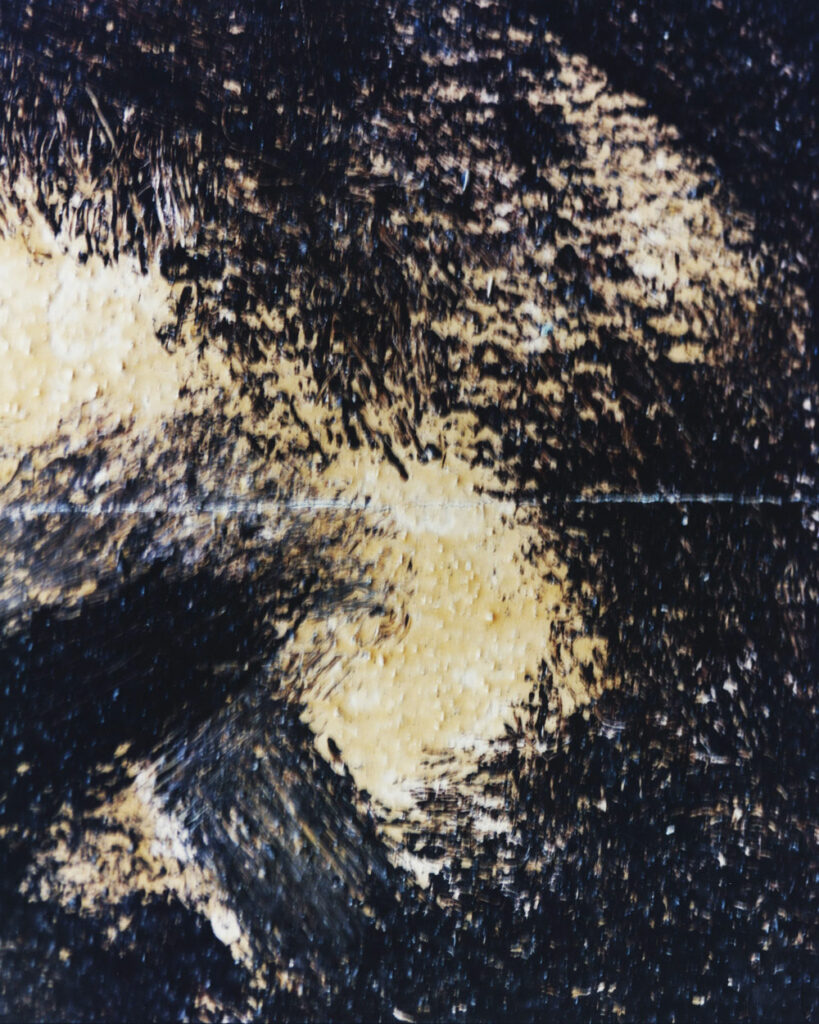

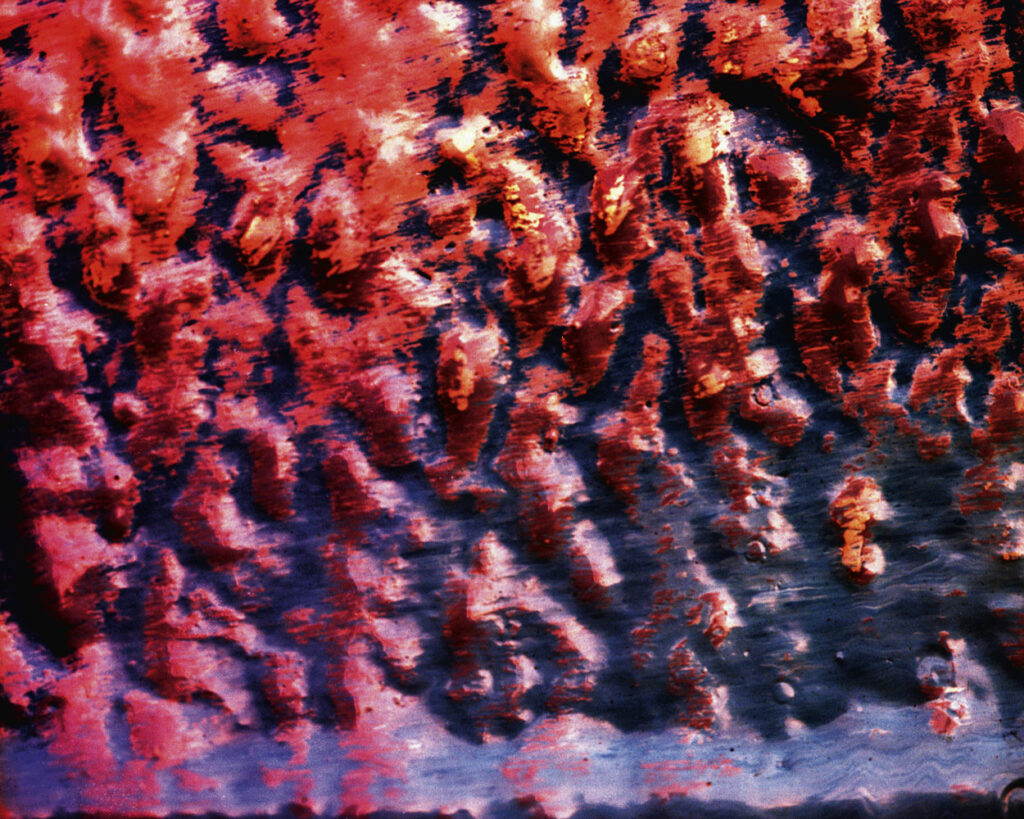

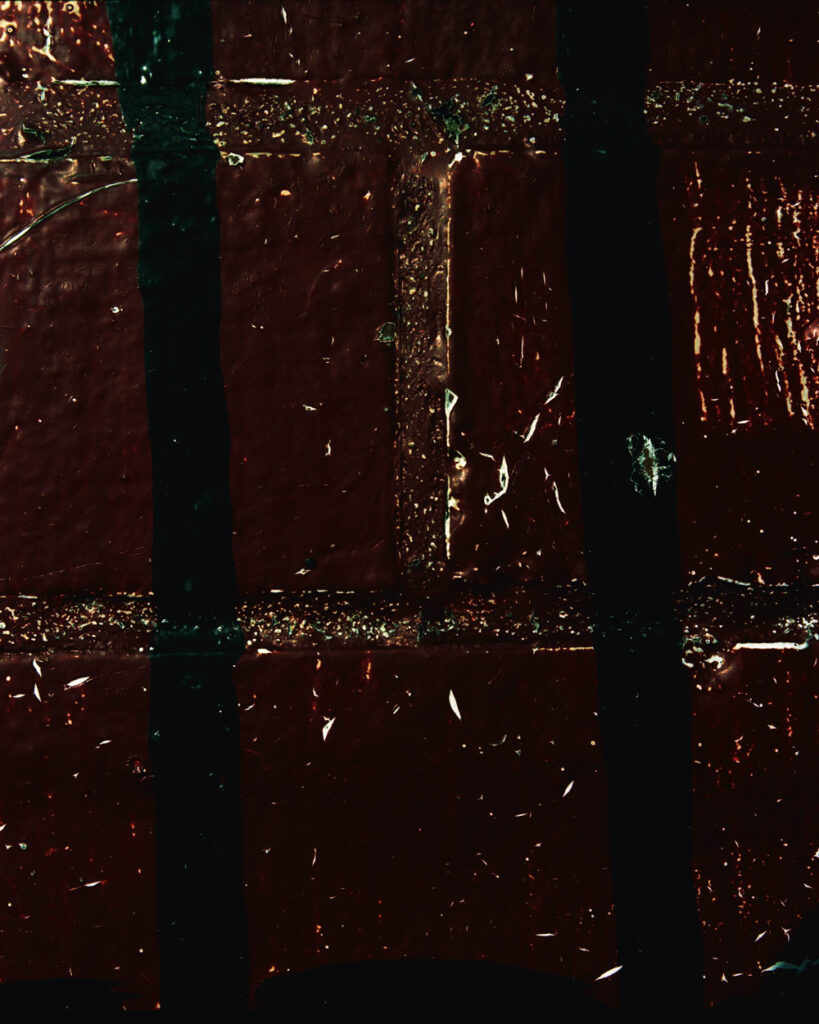

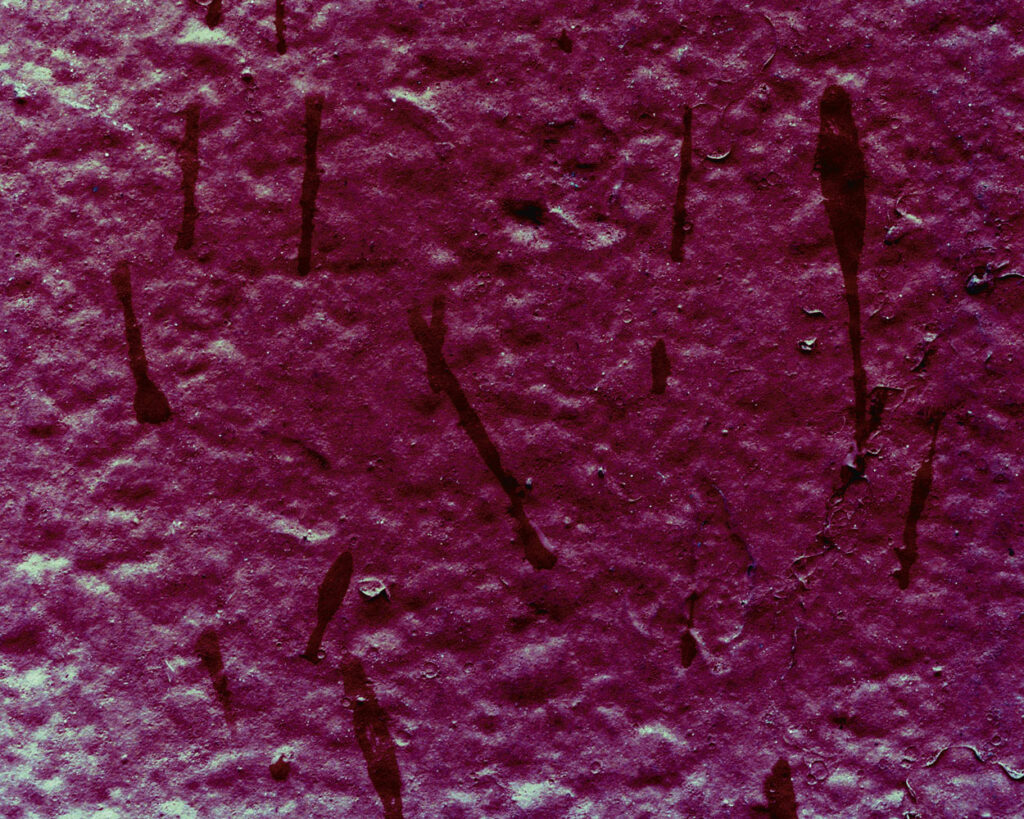

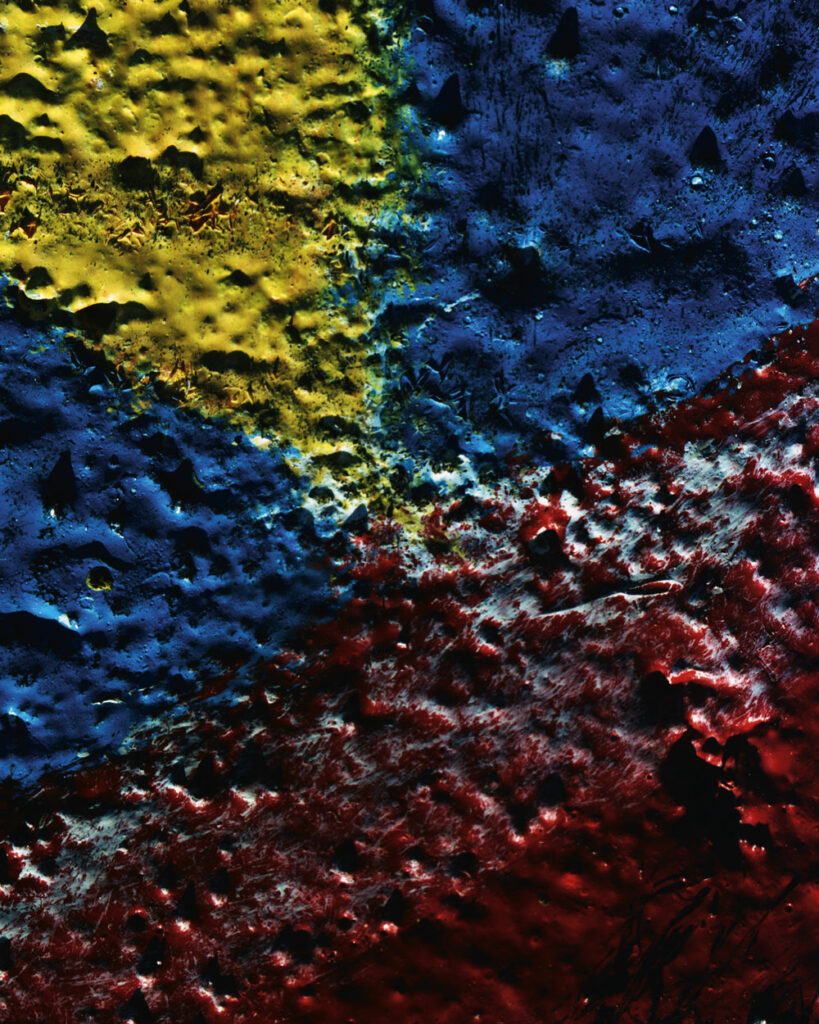

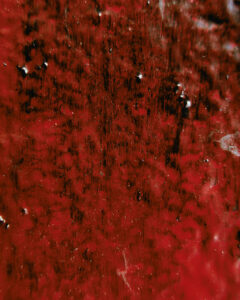

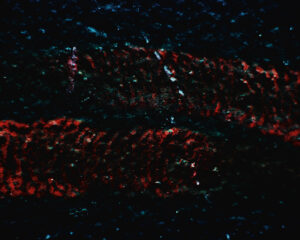

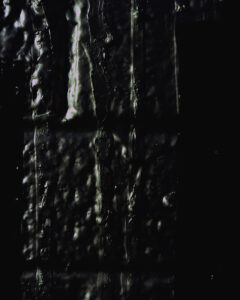

Works like ‘An Illusion’ seem to reference the construction of difference within an us/them discourse. In the photograph, black paint is slashed over a red ground in a broken cruciform shape, with flashes of white showing through. The title, ‘An Illusion’, seems to suggest the falsity of constructed identities which are predicated upon difference. His works also highlight the use of murals as mechanisms of not only identity but also memory. Using titles which suggest death, honouring of fallen comrades and memorial, he explores the ways murals represent the past in order to legitimize the present. In ‘For Evermore’, a blood-red field is bisected by a thick black stripe of paint. The title may reference the use of murals as memorials to those killed fighting for a cause. One such example is a Belfast UVF mural painted with the slogan “UVF. For God and Ulster. Like Acts of Valour, their sacrifice live with us for evermore” underneath portraits of two early twentieth century unionist political figures and two UVF volunteers killed in 1977 and 1988.19 By aligning UVF members killed more recently with celebrated political figures of the past, the muralists imply a historic continuity of cause and sacrifice. However, in ‘For Evermore’, as in ‘Dark Days’, the uppermost layer of paint has peeled off in areas, revealing layers underneath and implying the ephemeral quality of murals and of memory. ‘For evermore,’ therefore, may only be until the wall is re-used for new imagery.

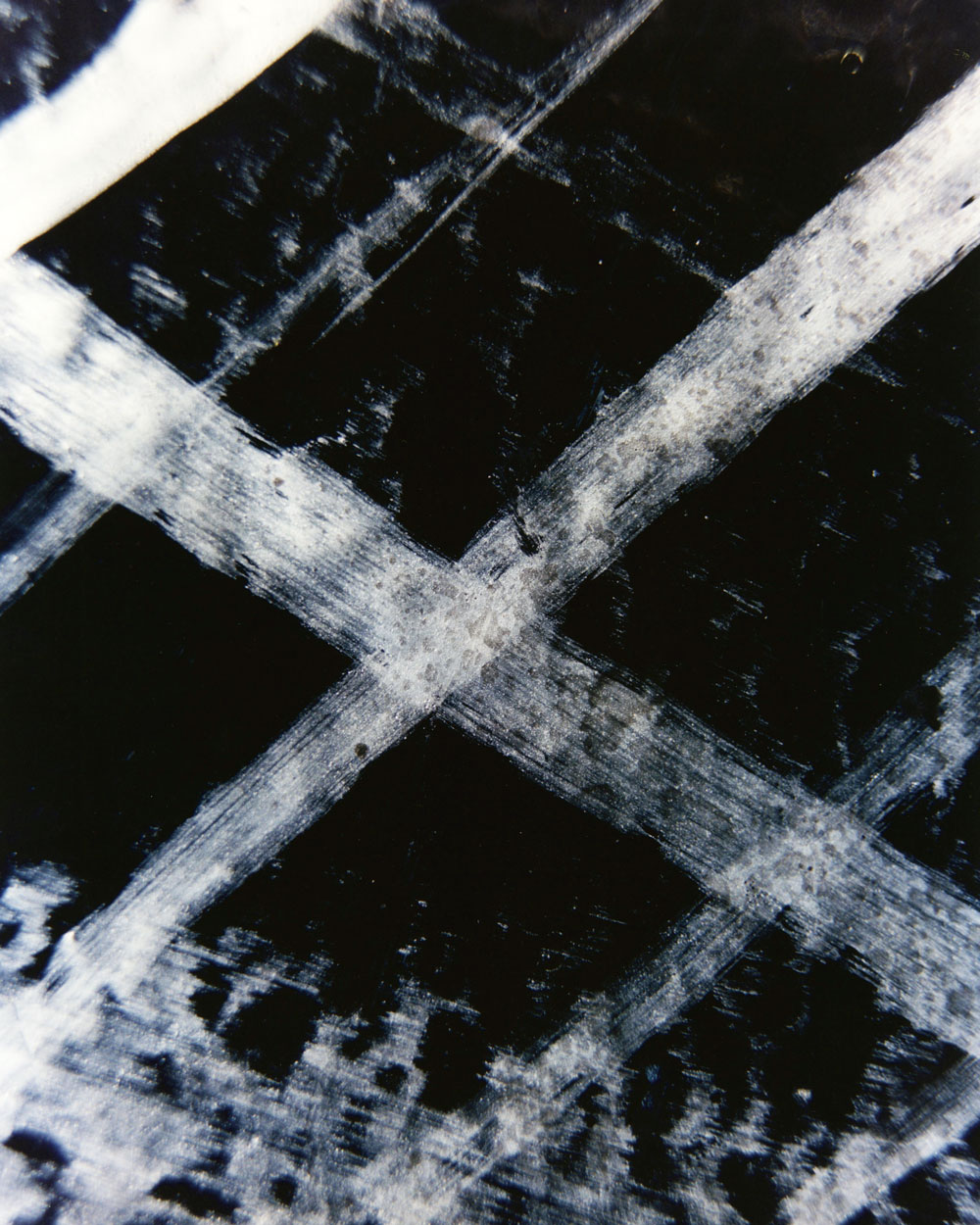

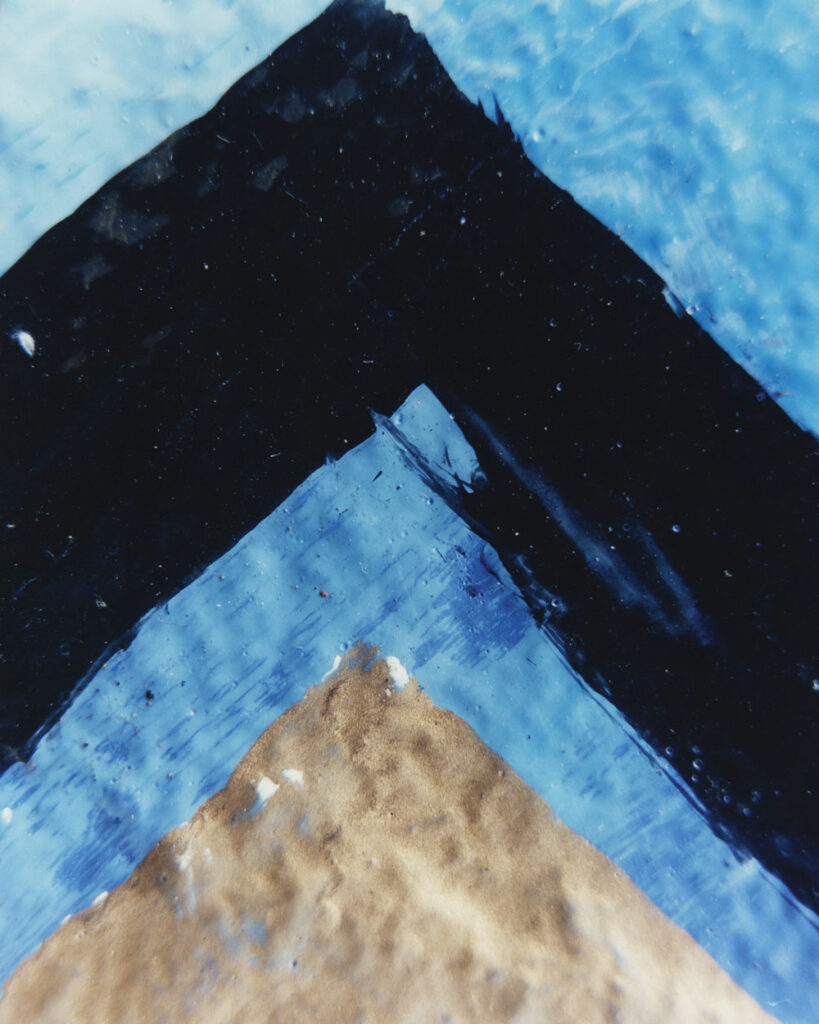

Another work, ‘State Murder’, in which again a blood-red field is split by thick lines of paint, both black and white here, echoes the use of the phrase “collusion is state murder” in nationalist murals. These murals act as both memorial to dead nationalists and indictments of a corrupt system of power, connecting a systemic problem with specific occurrences. In both cases, the murals symbolically represent the past as a way to understand the present. Paul Connorton argues that social memory is dependent on the construction of the present through knowledge of the past: “We experience our present world in a context which is causally connected with past events and objects, and hence with reference to events and objects which we are not experiencing when we are experiencing the present.” Hence, by selecting which events and people from the past are memorialised and how, muralists are able to influence discourses of the present. McConnell has stated that he sees his images of the murals as moving beyond political rhetoric “in search of something more absolute, more aesthetic, more peaceful even.” He sees in the murals a strive toward abetter future which has been distorted by politics. McConnell’s images fragment and abstract murals in order to move past narratives of sectarian difference and explore more universal ways in which history and identity intersect.

Shannon Flaherty