Dream Meadows

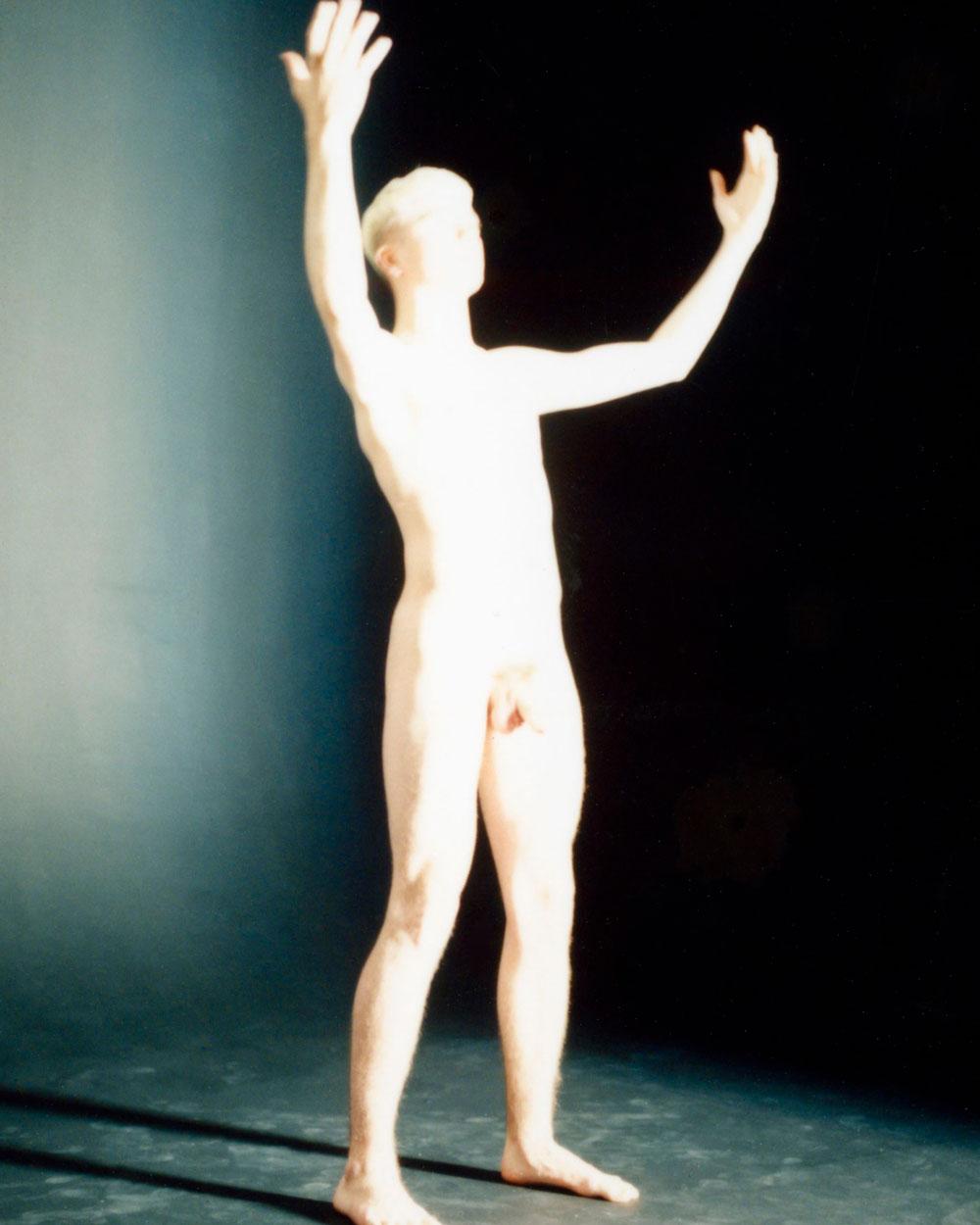

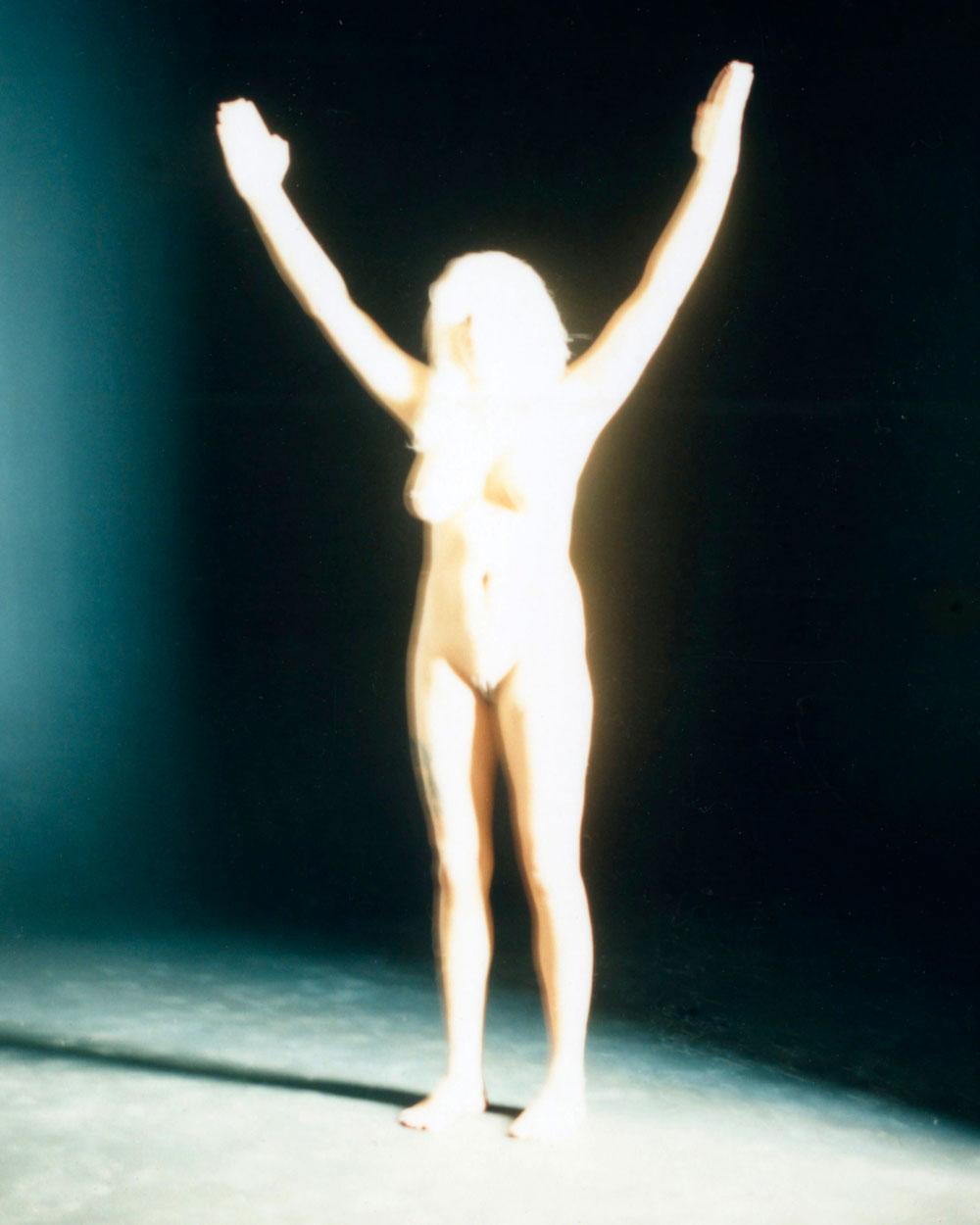

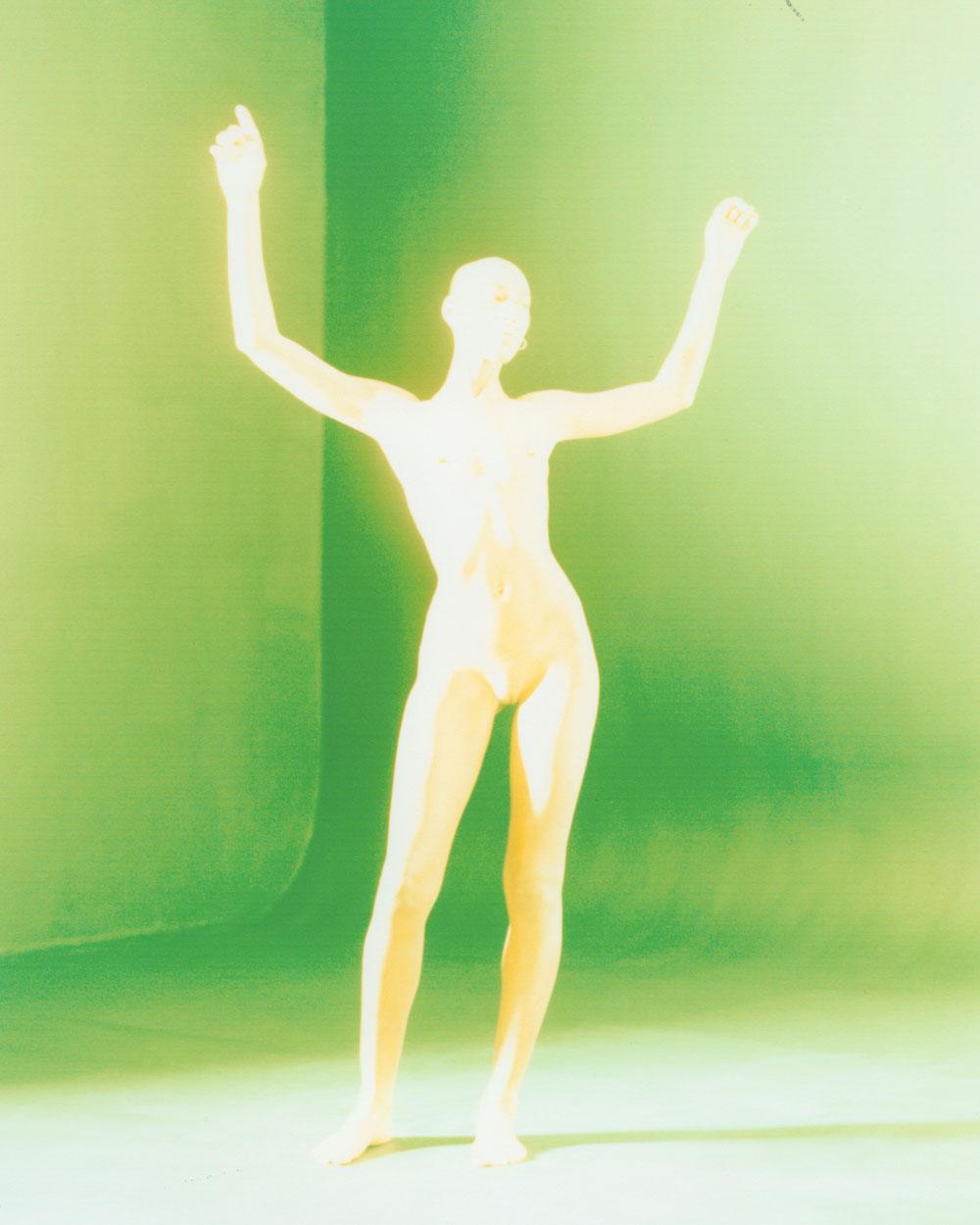

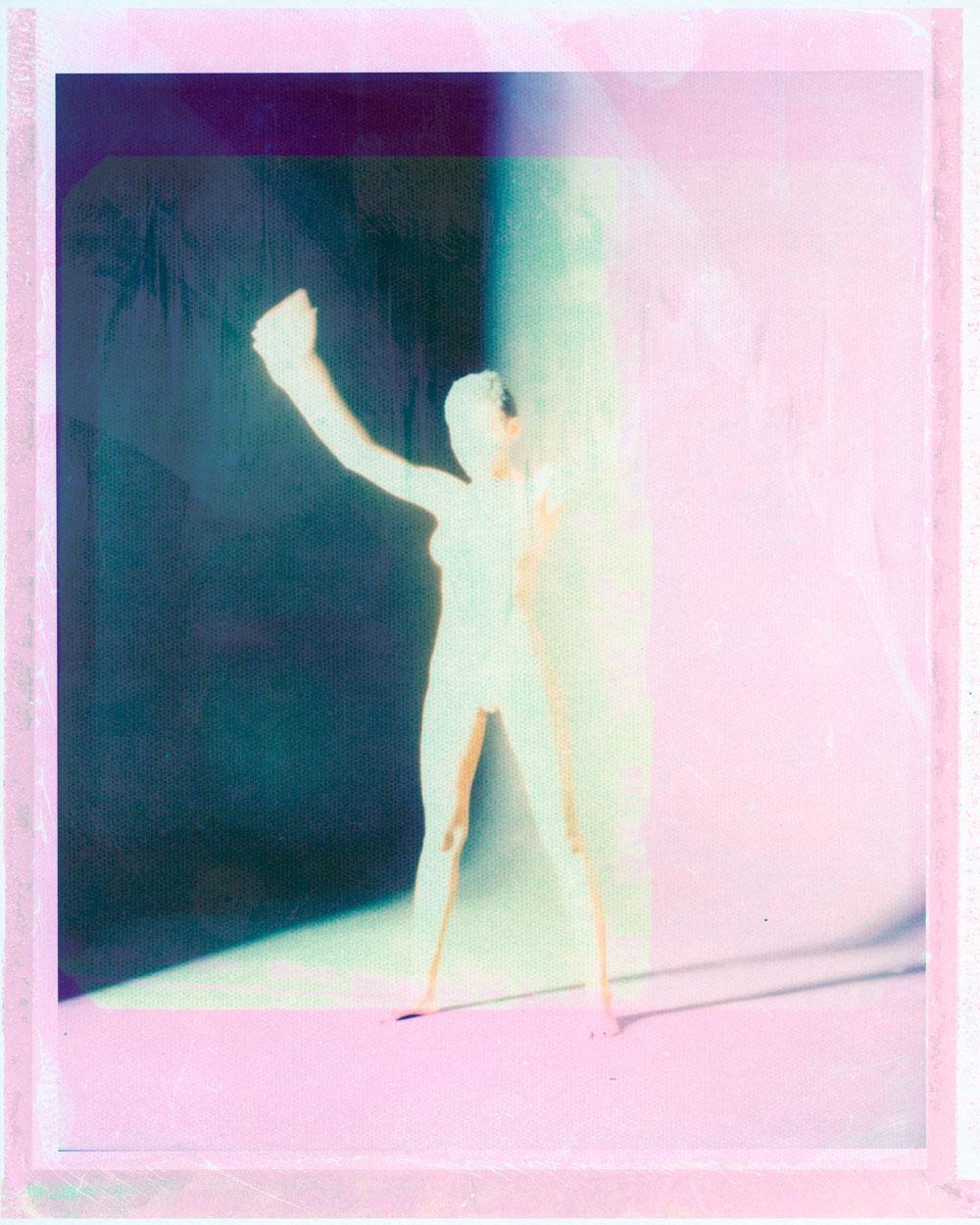

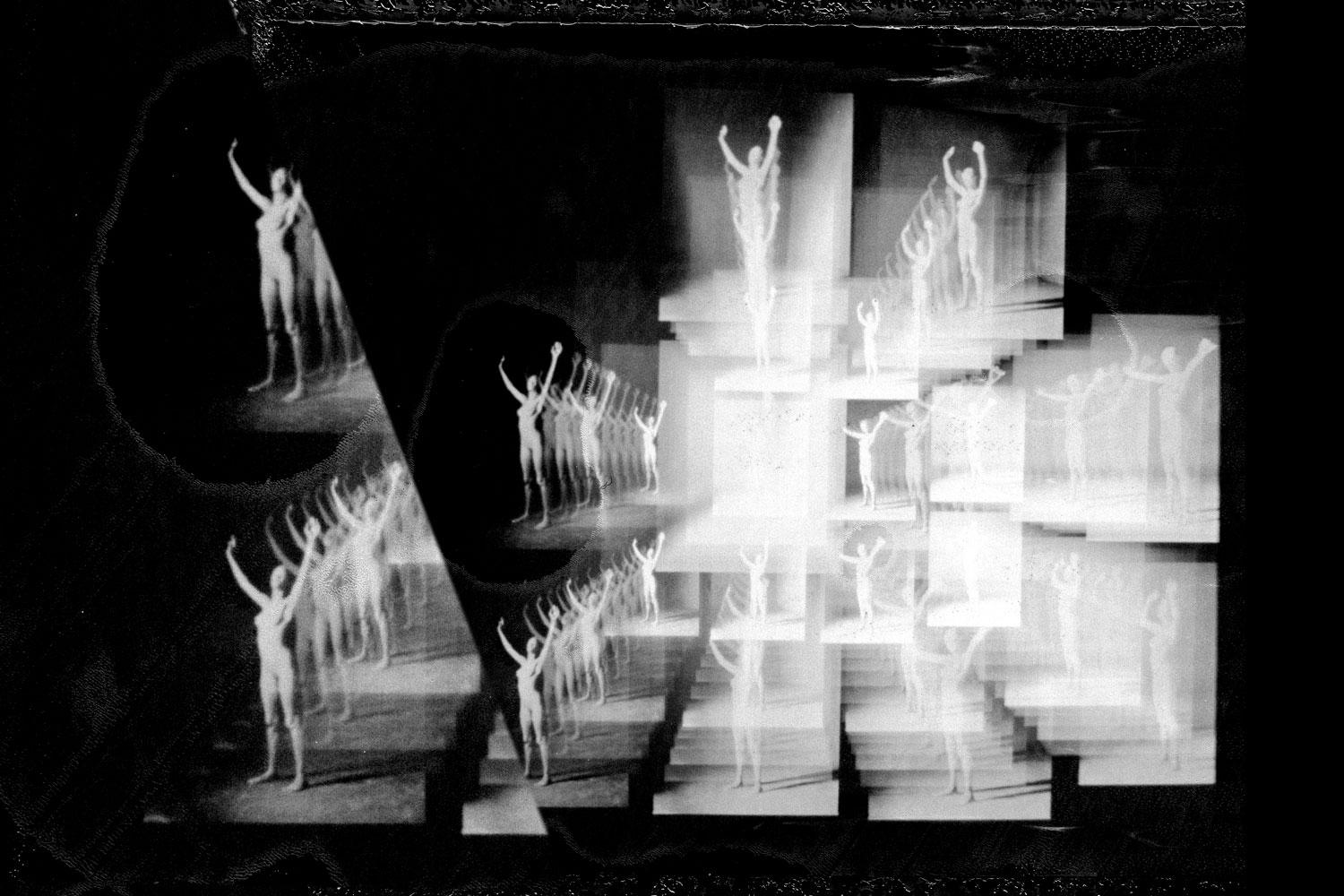

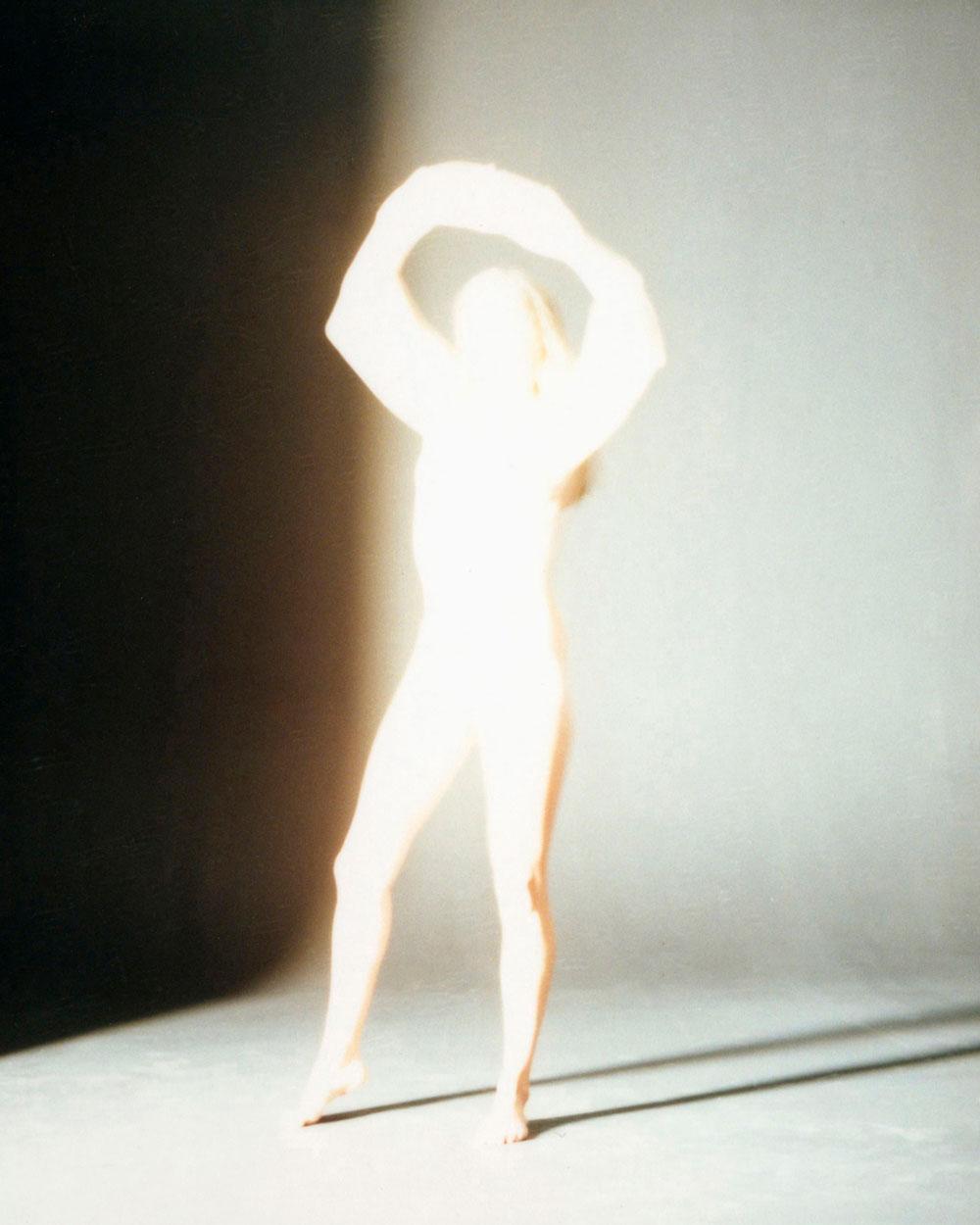

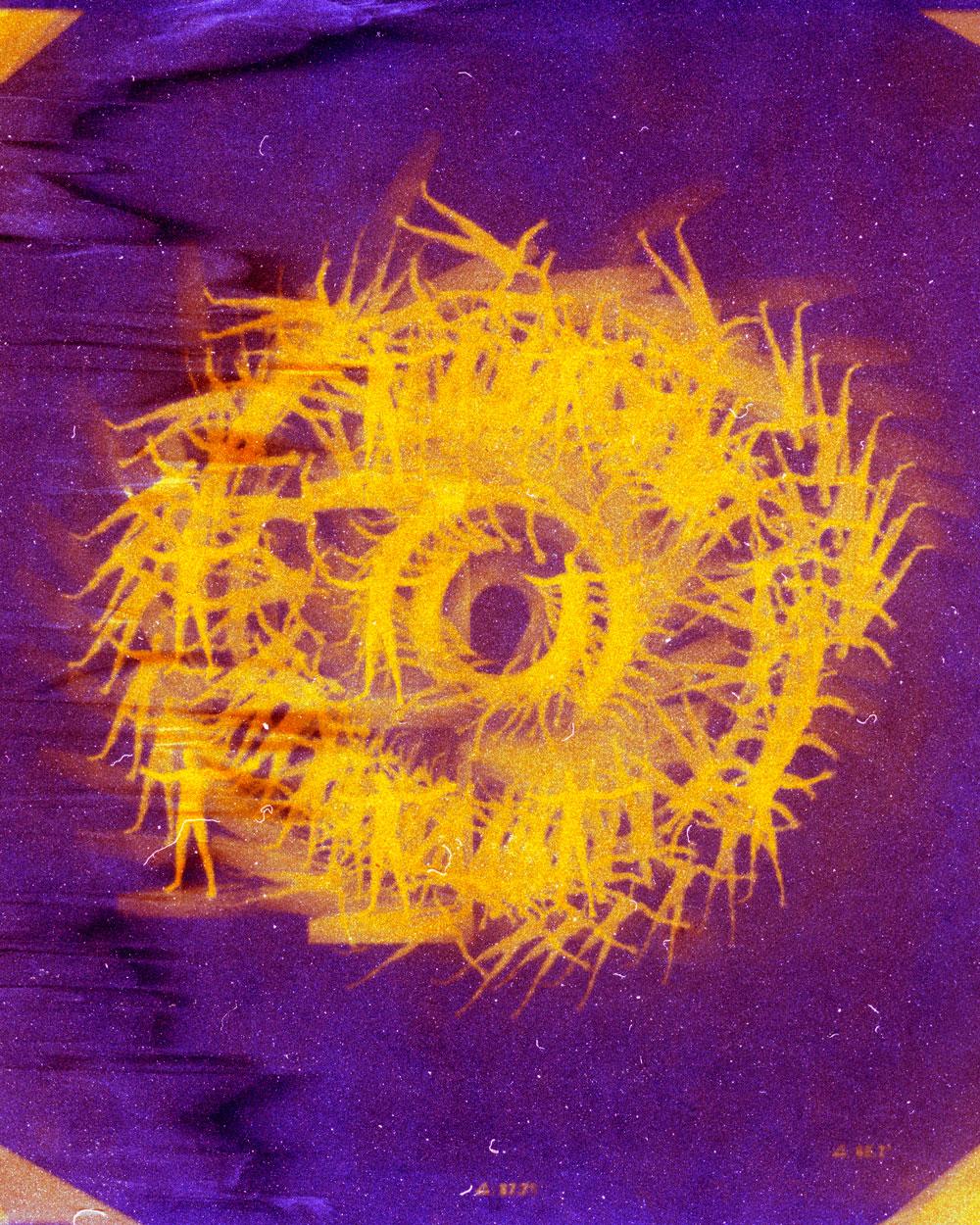

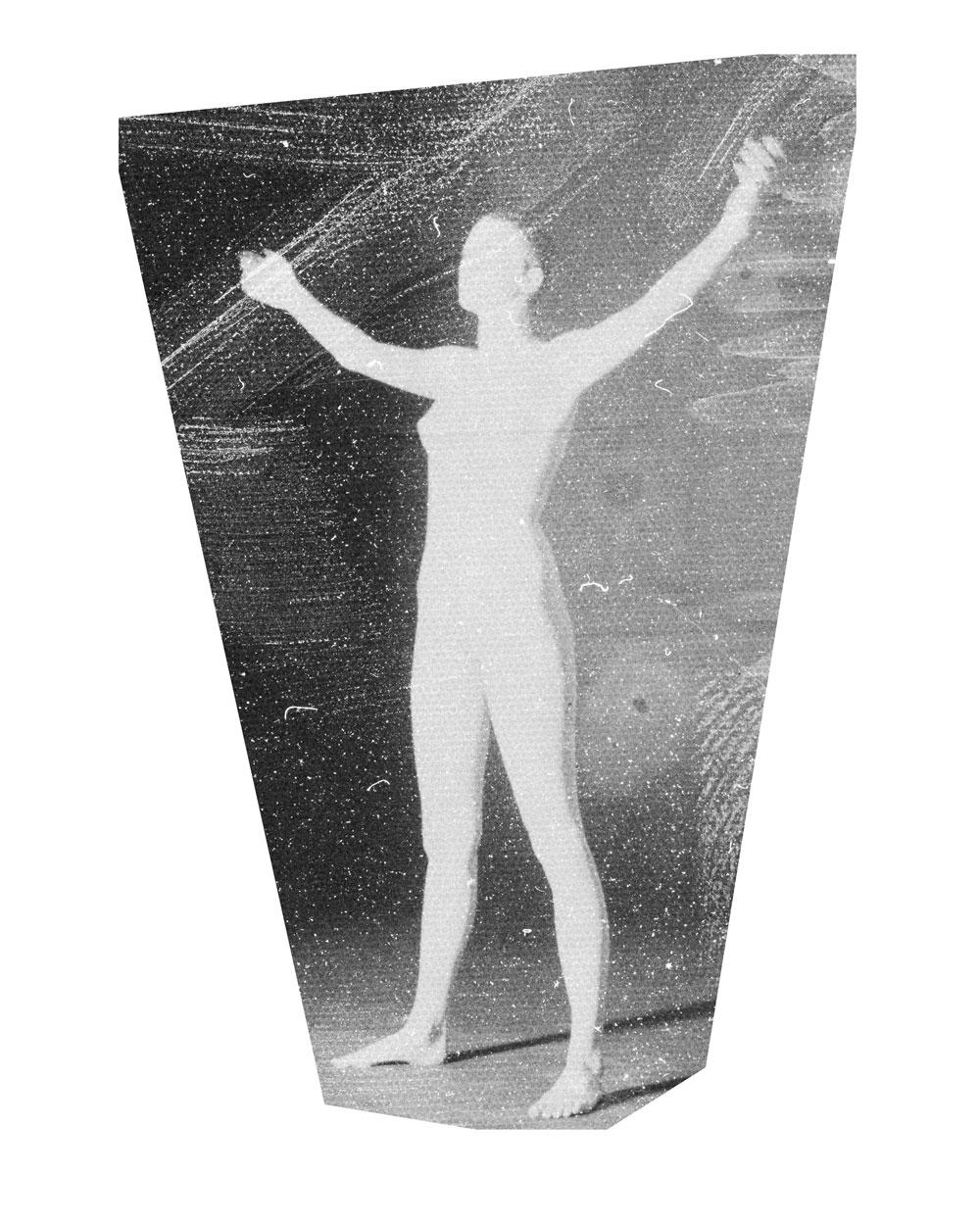

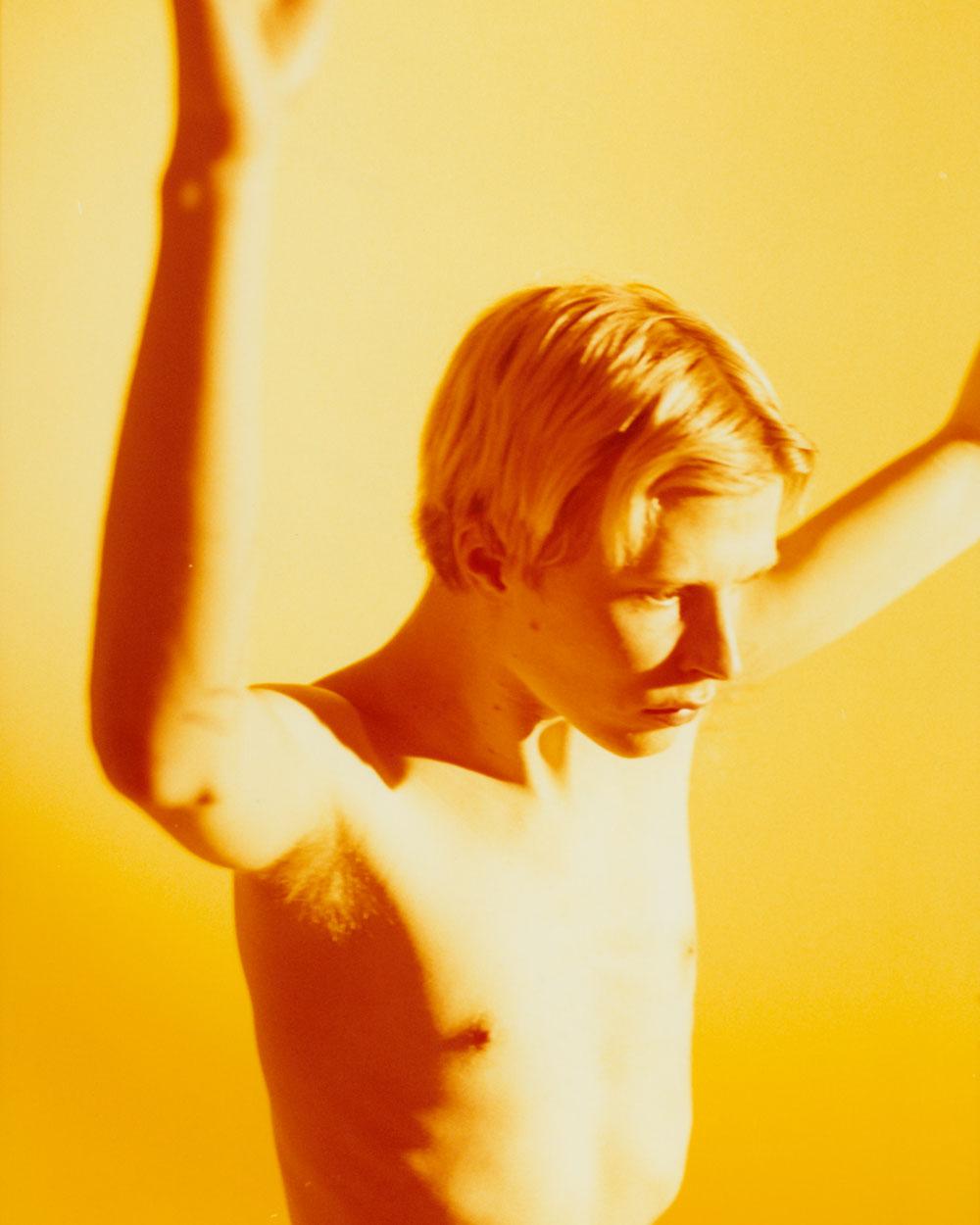

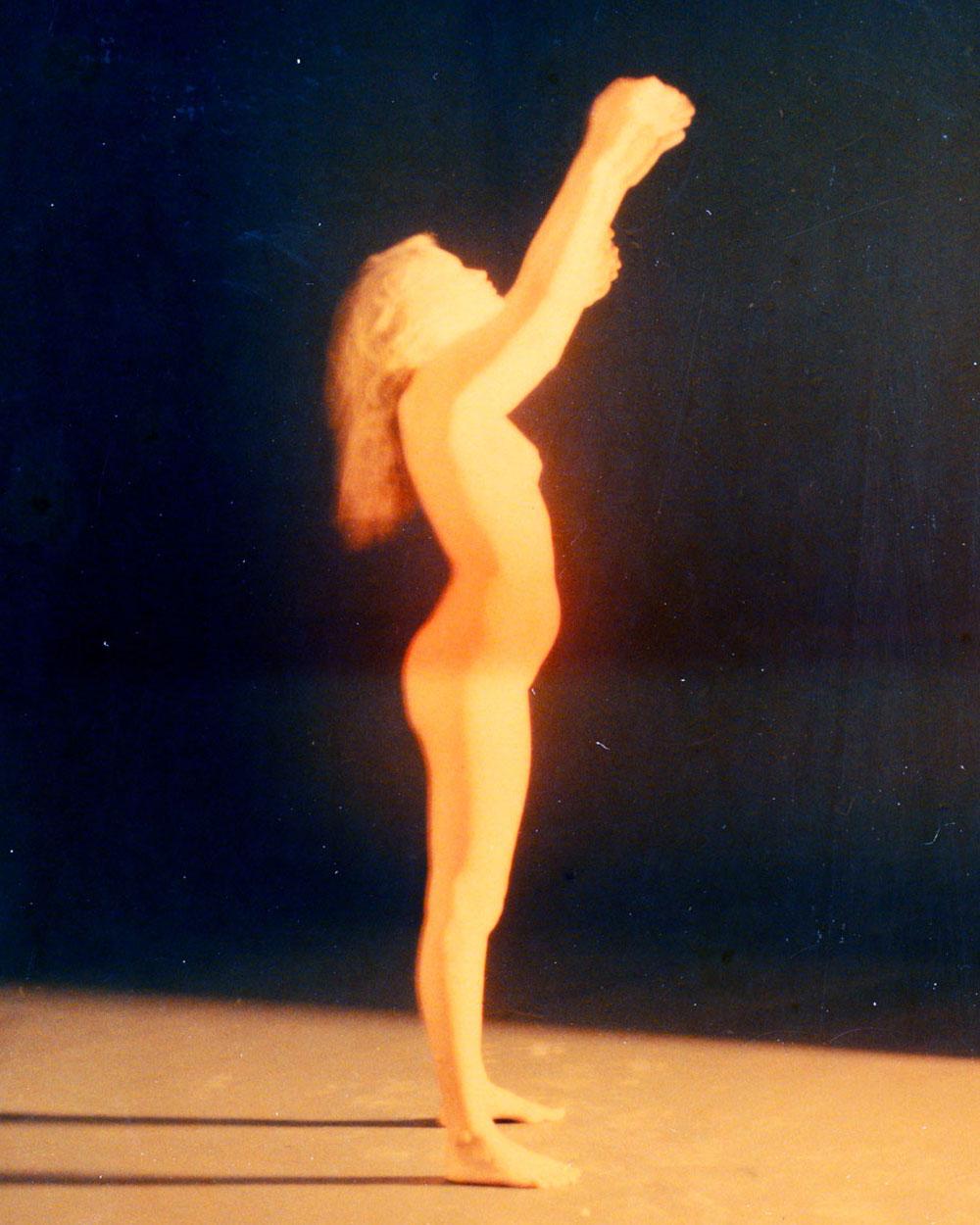

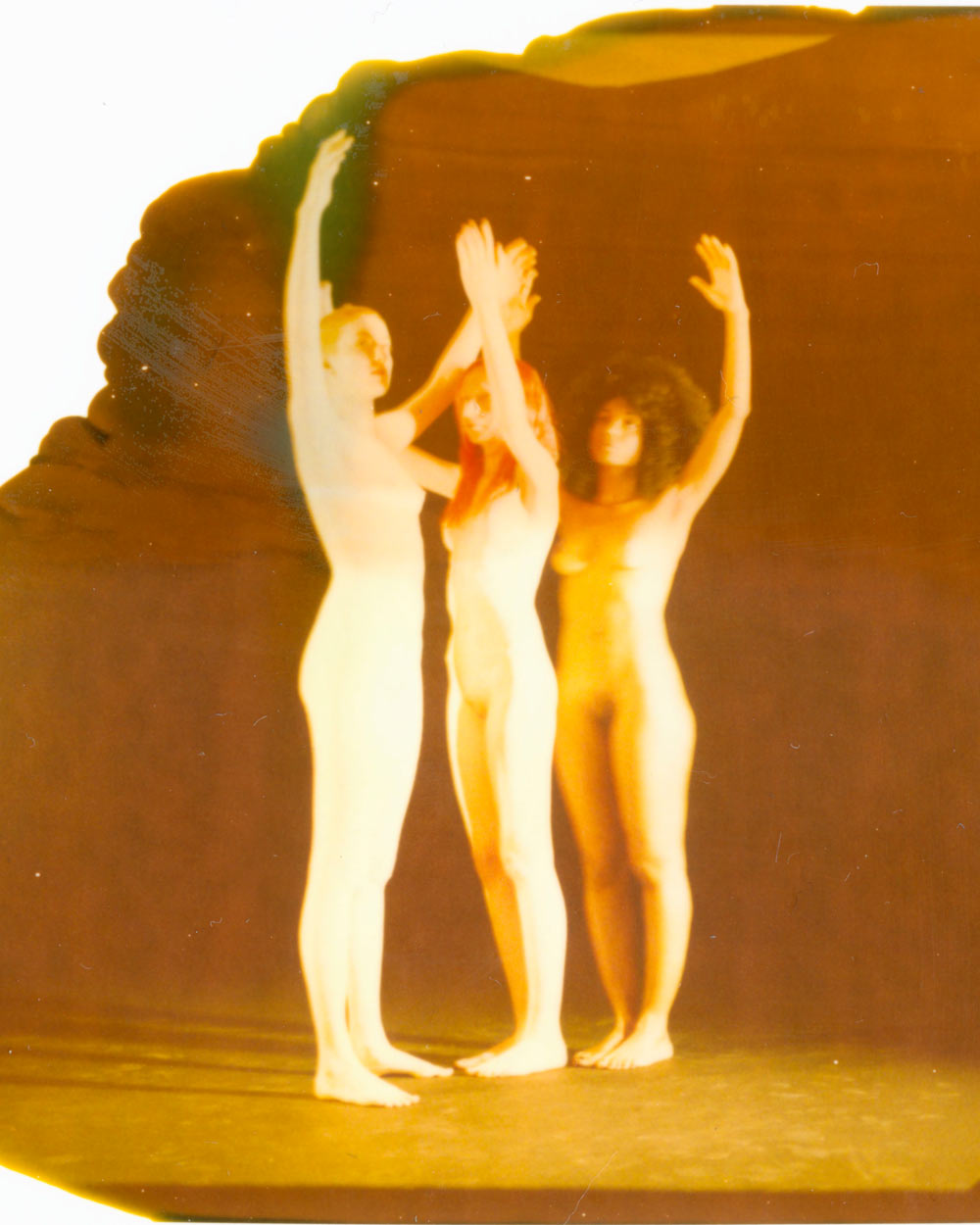

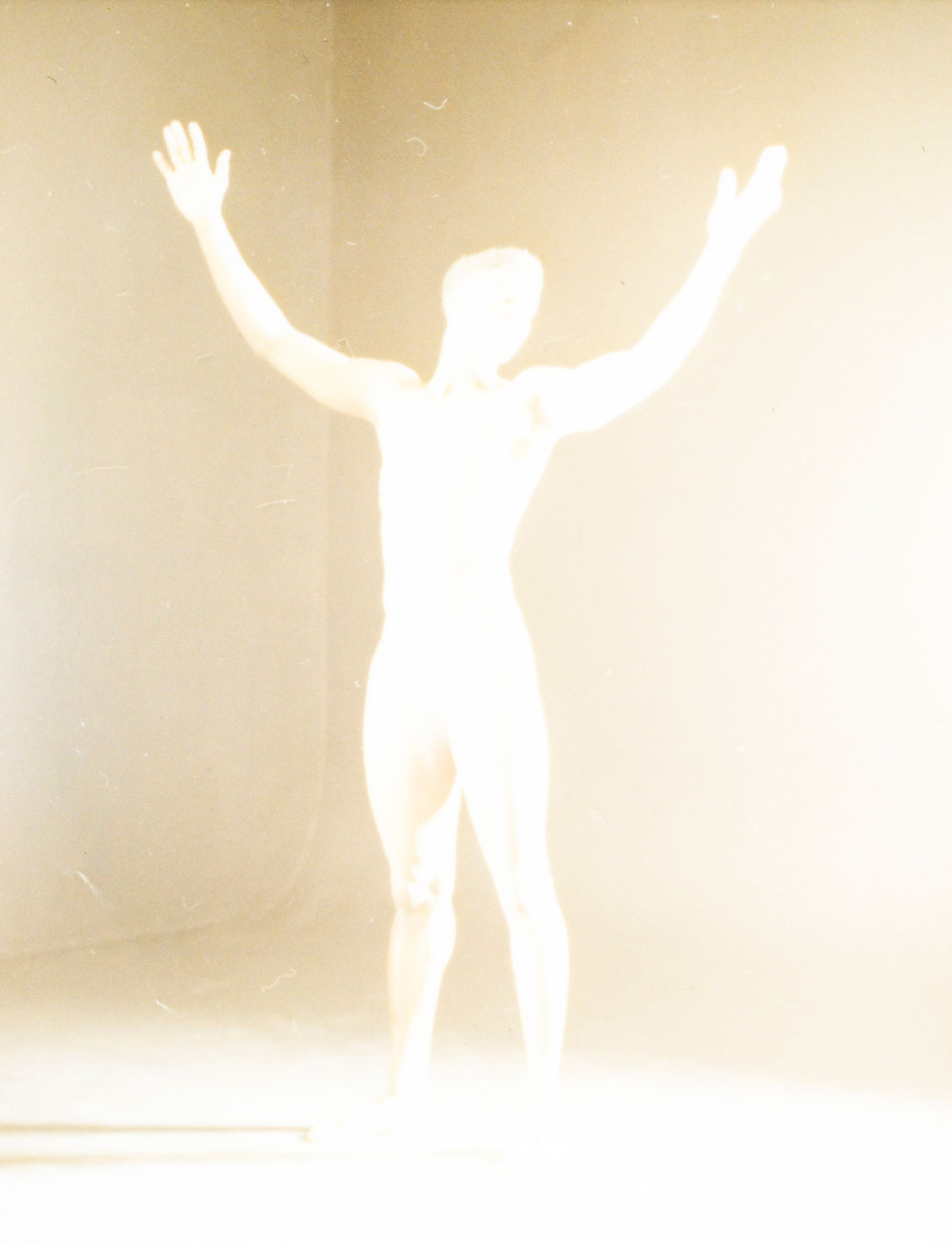

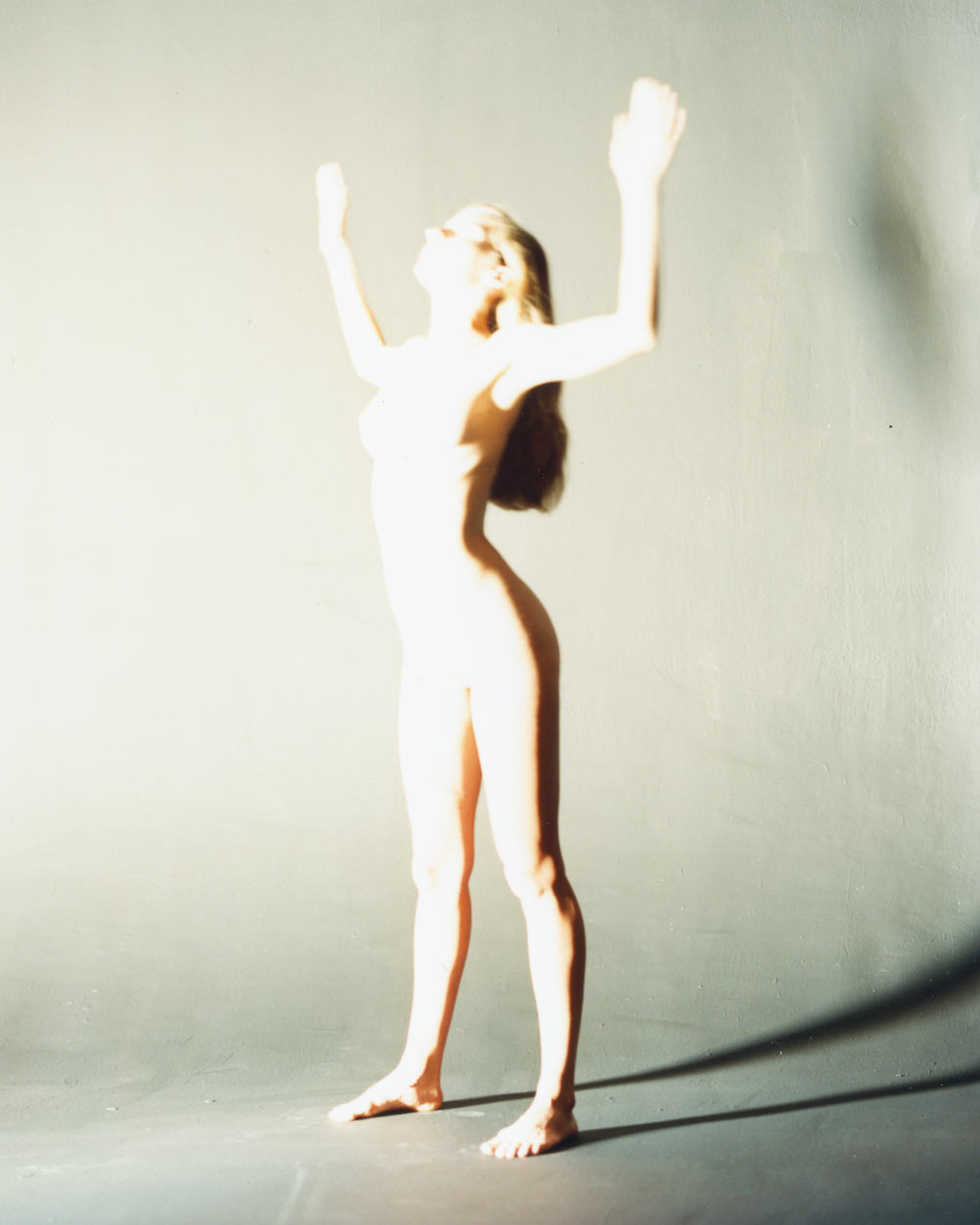

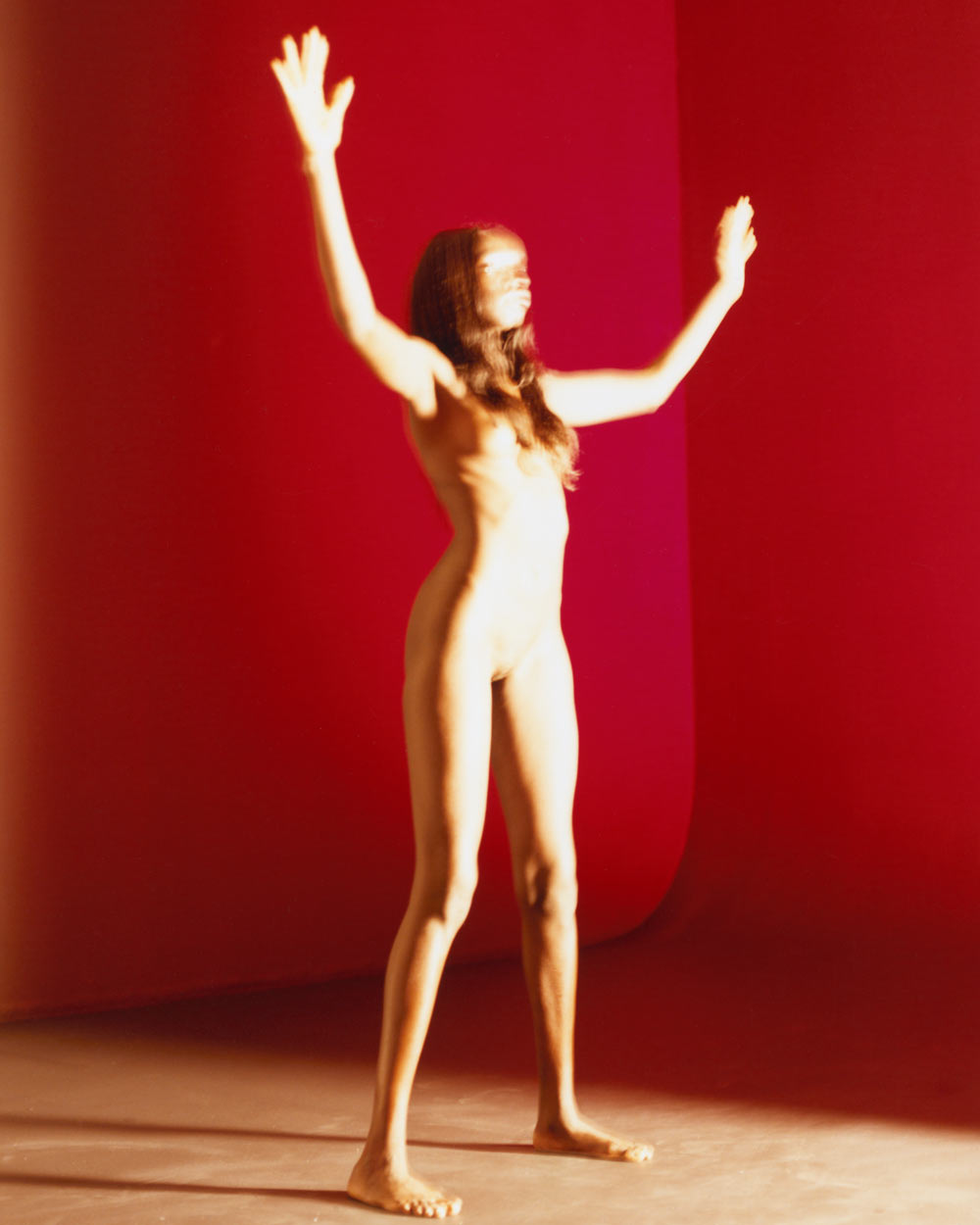

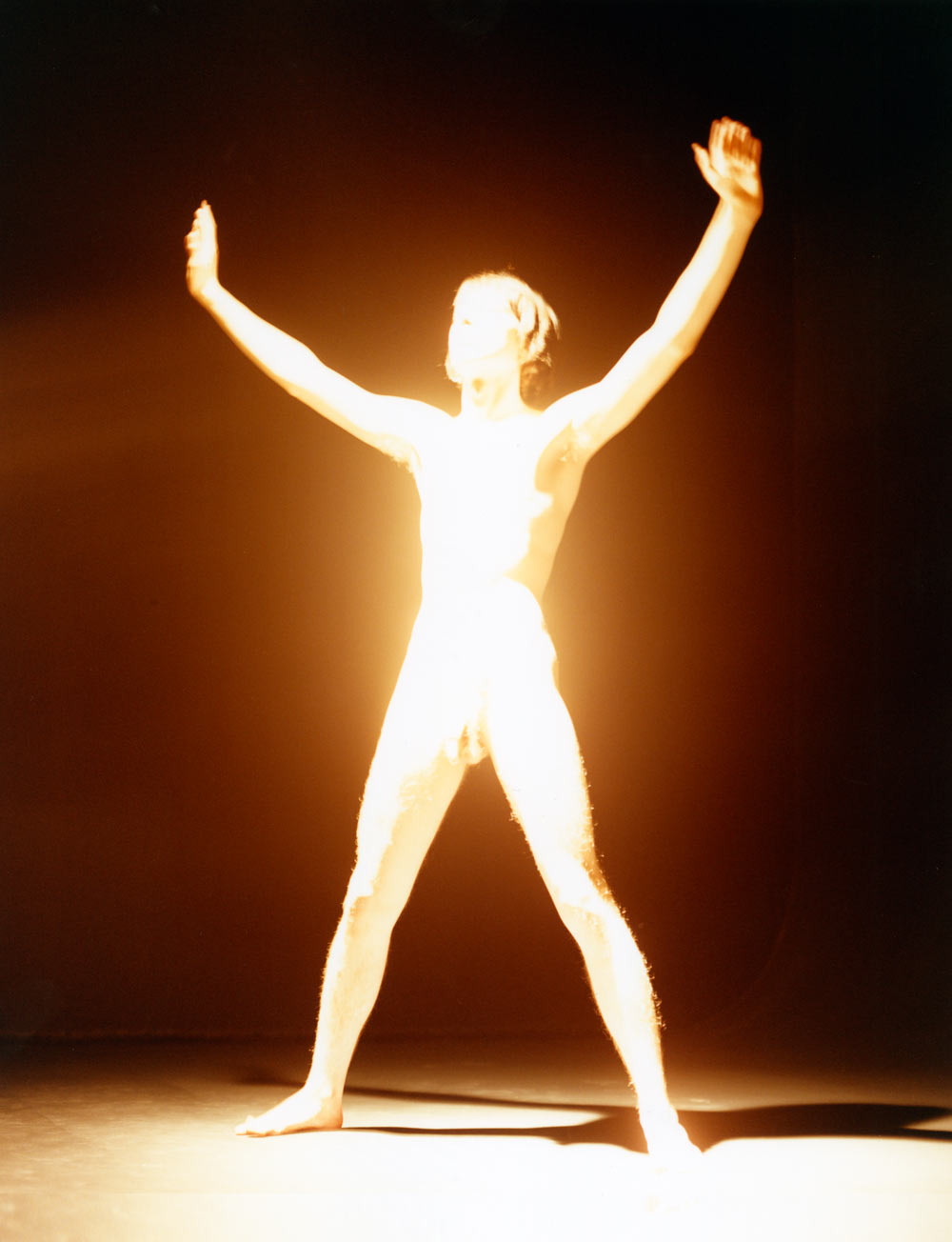

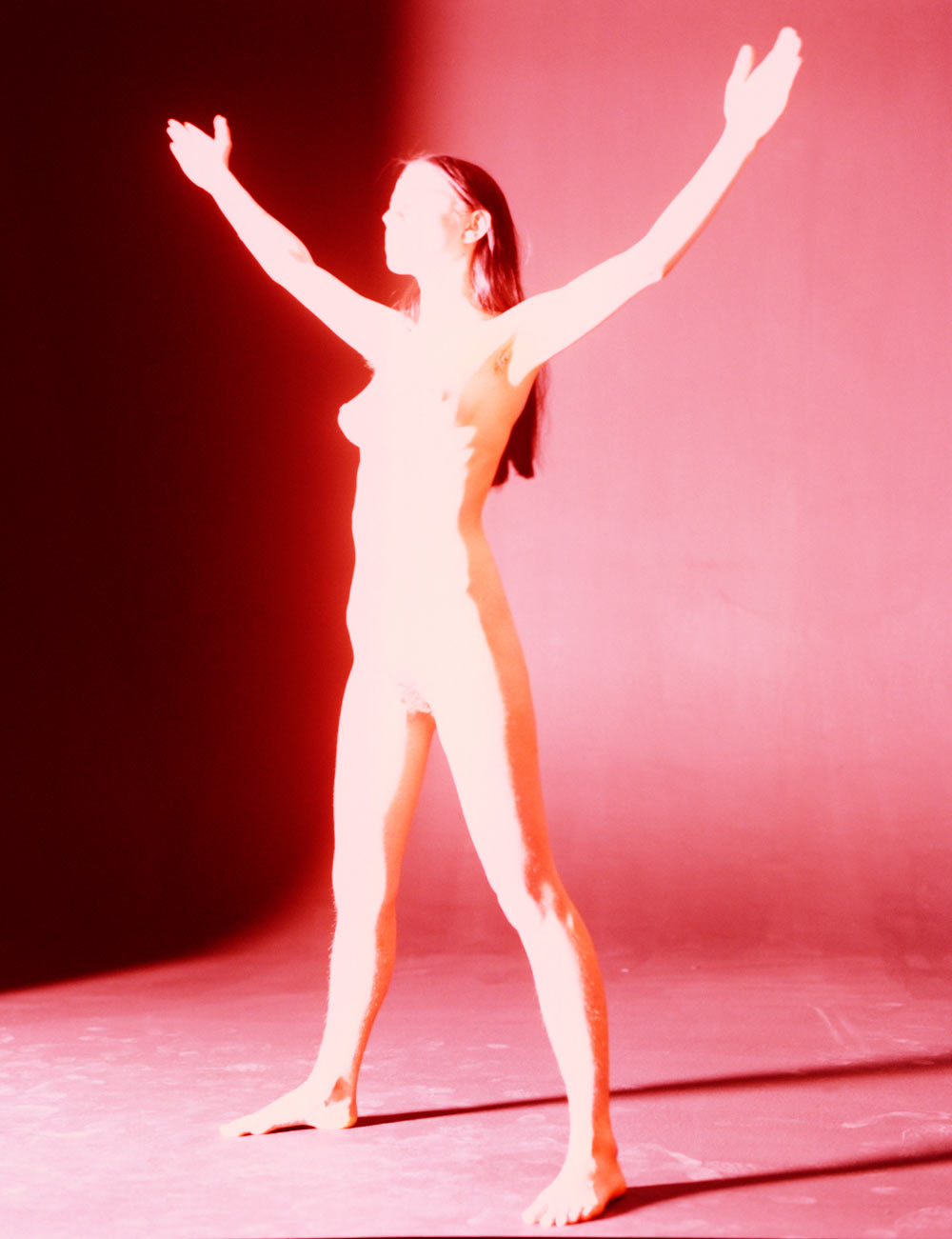

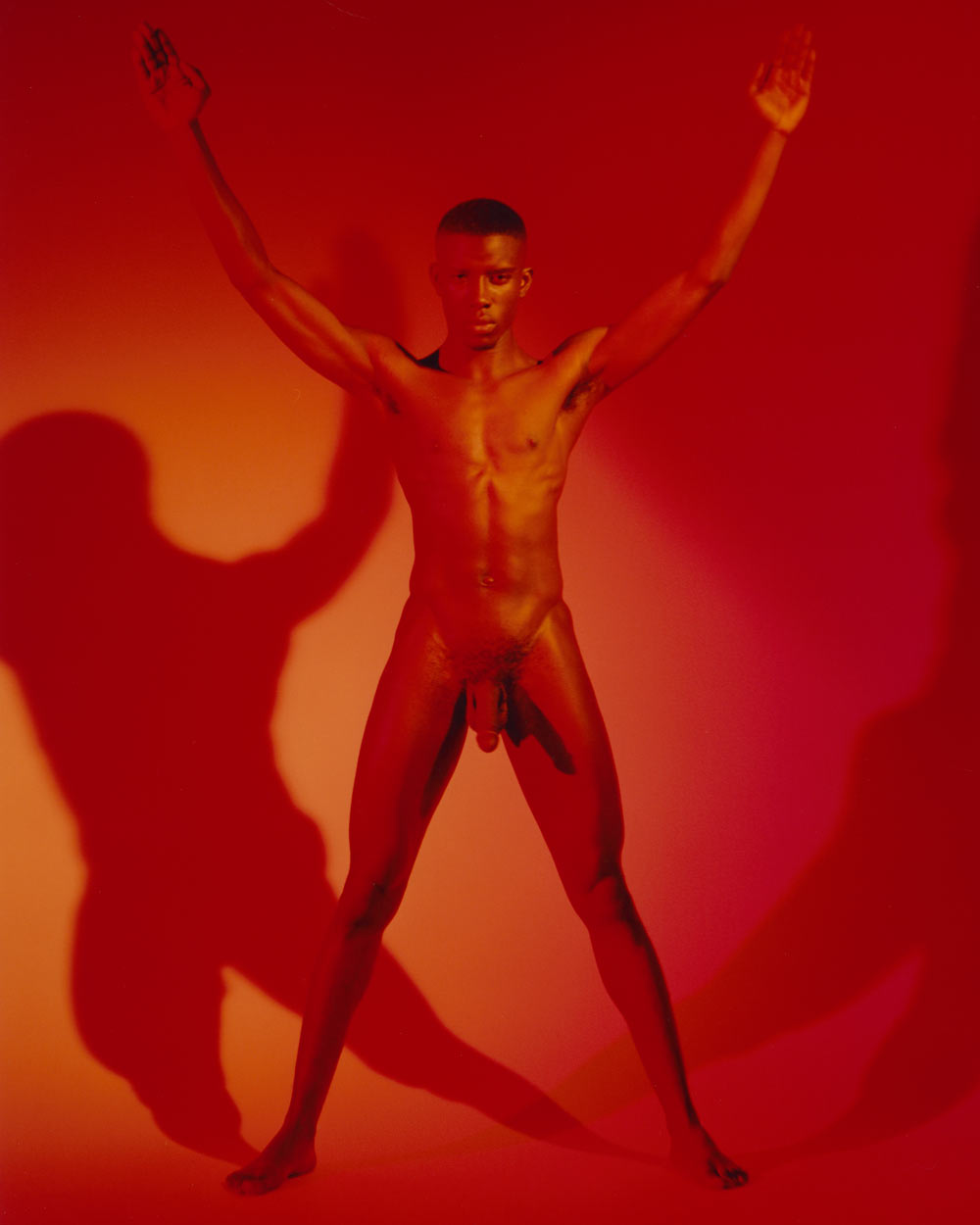

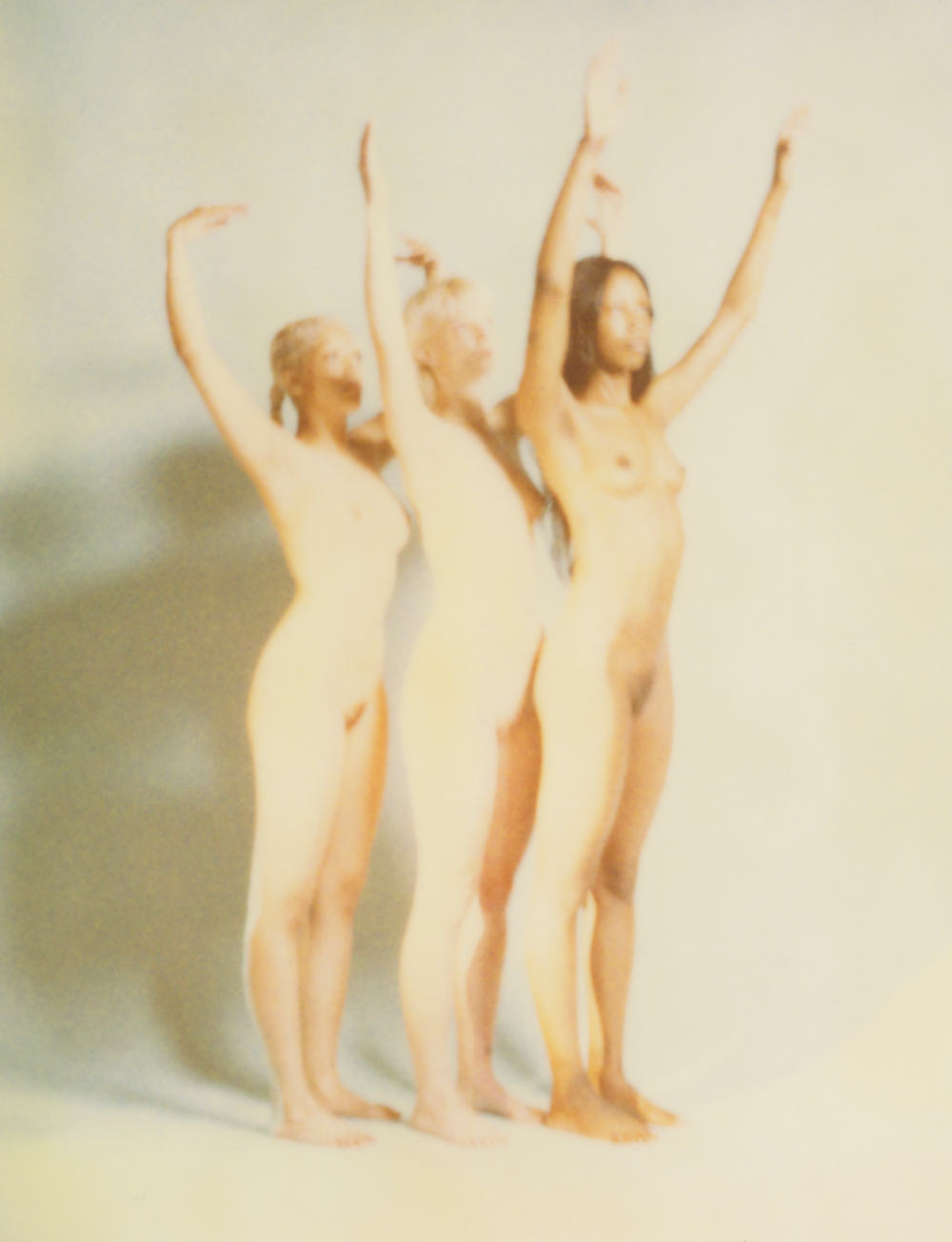

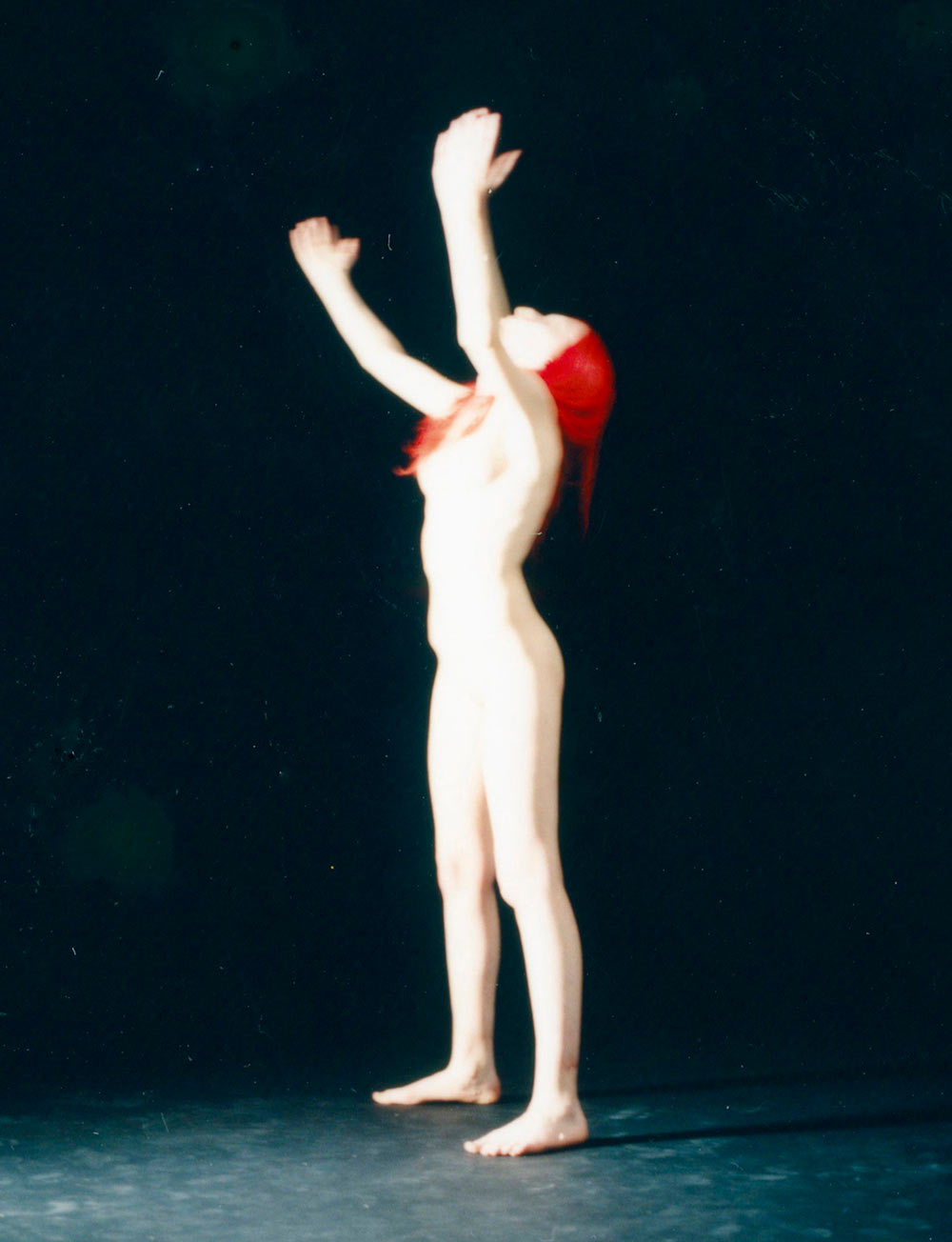

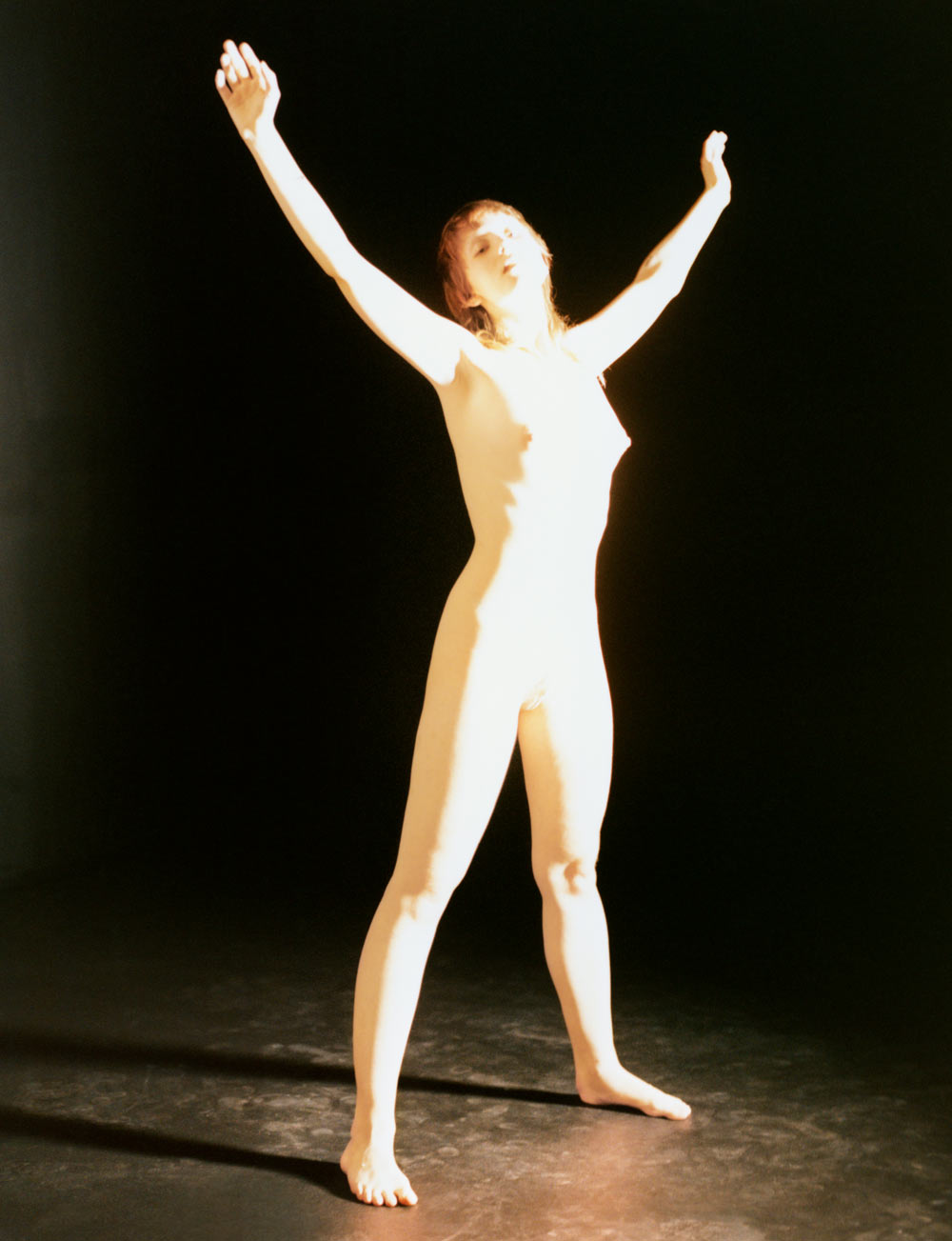

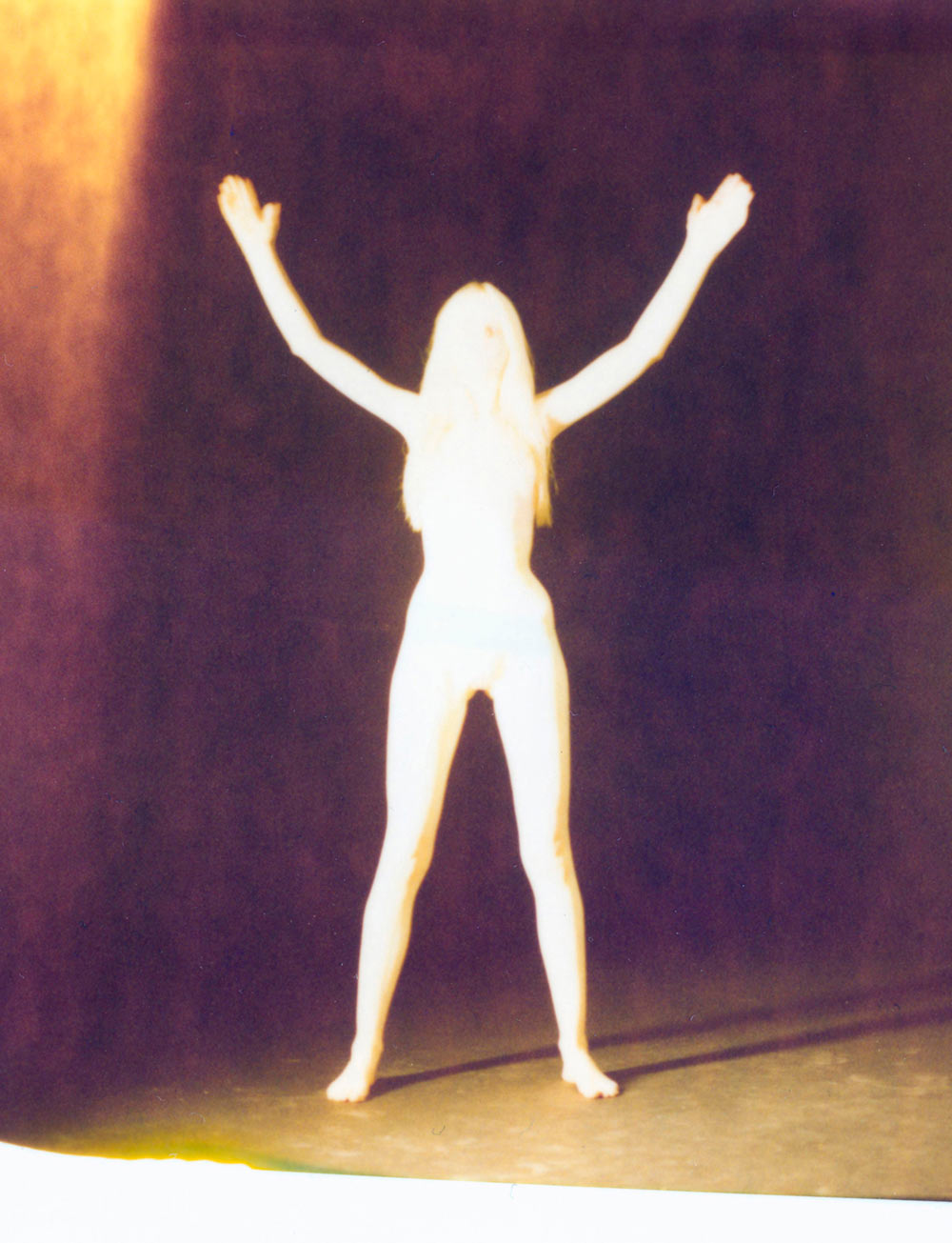

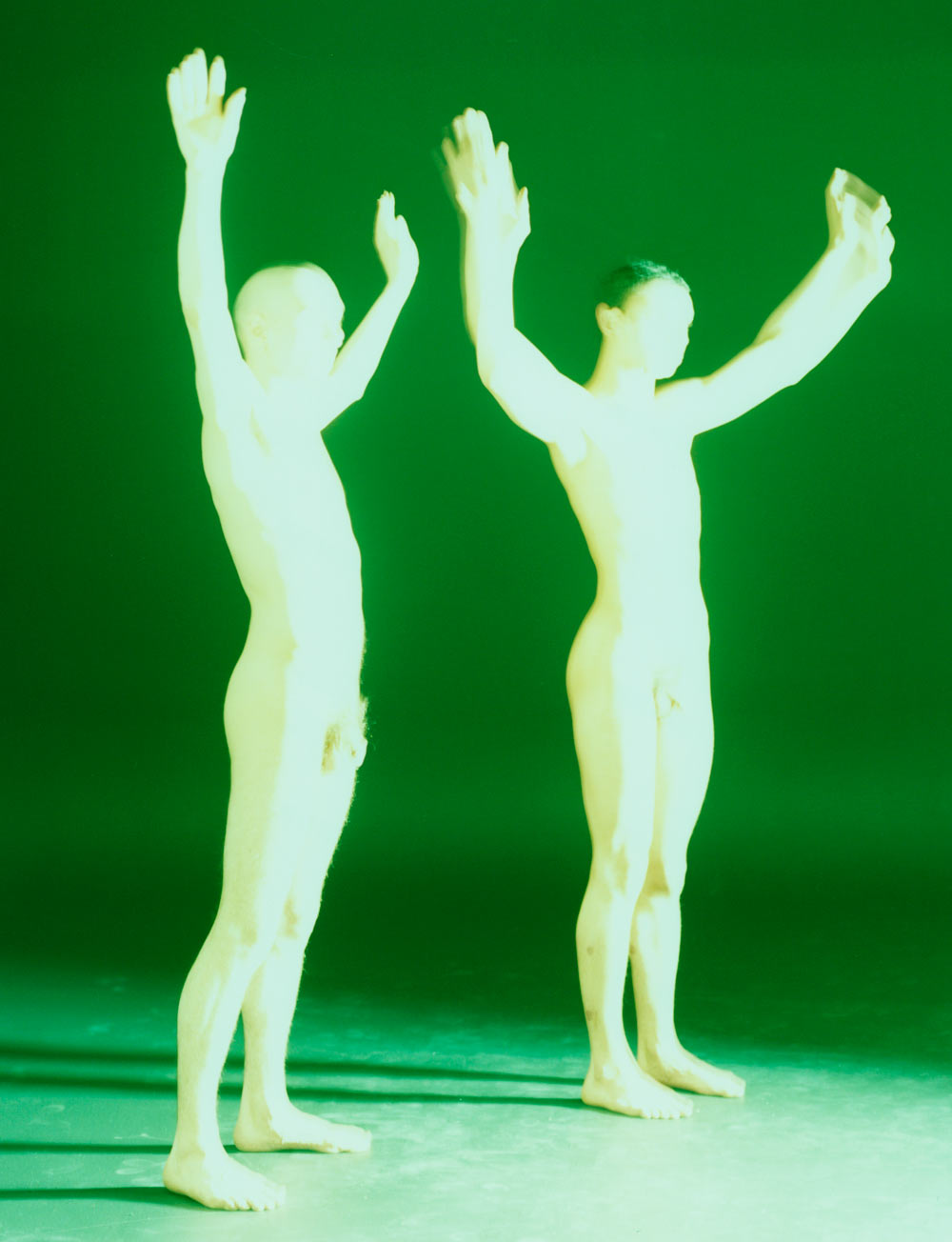

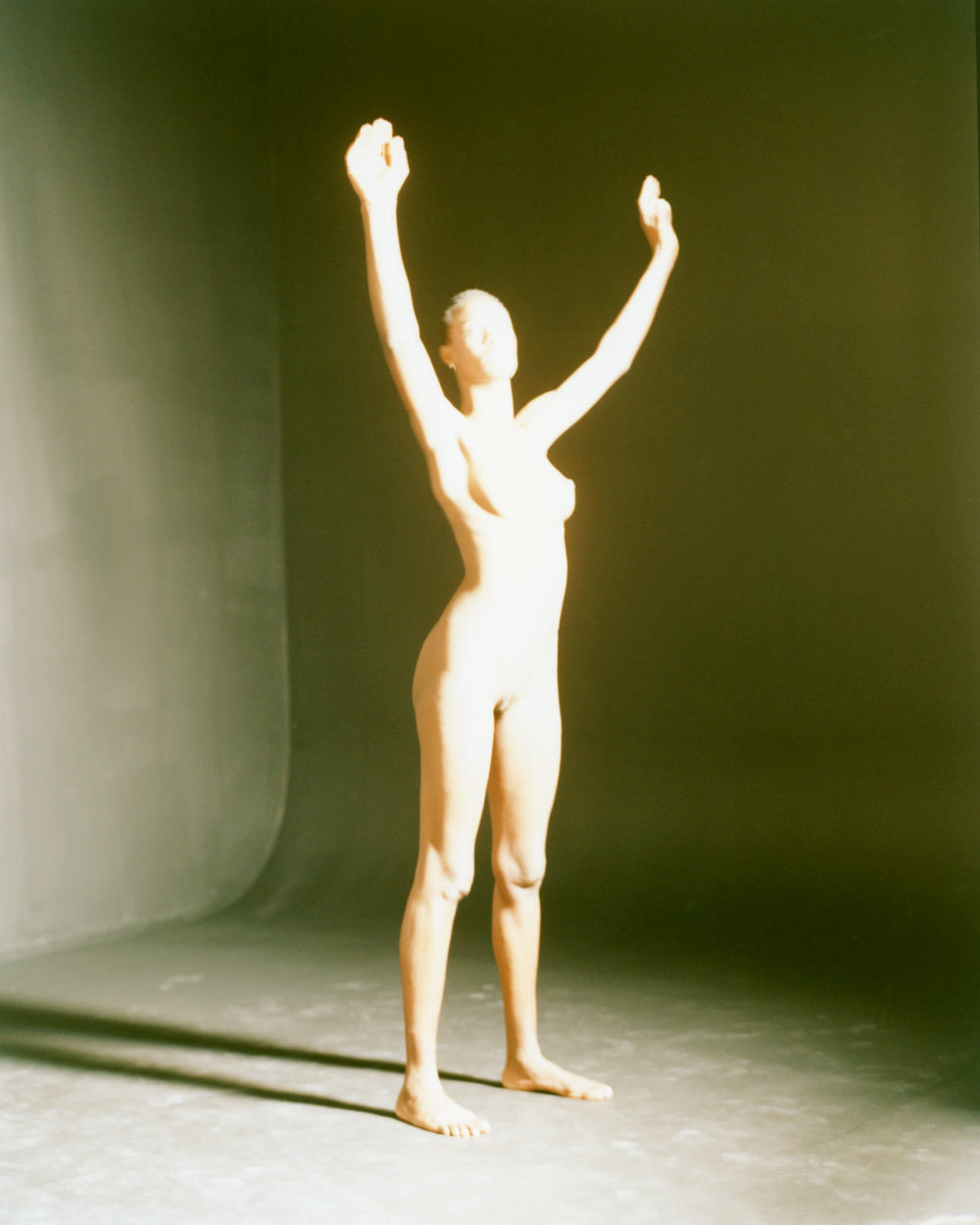

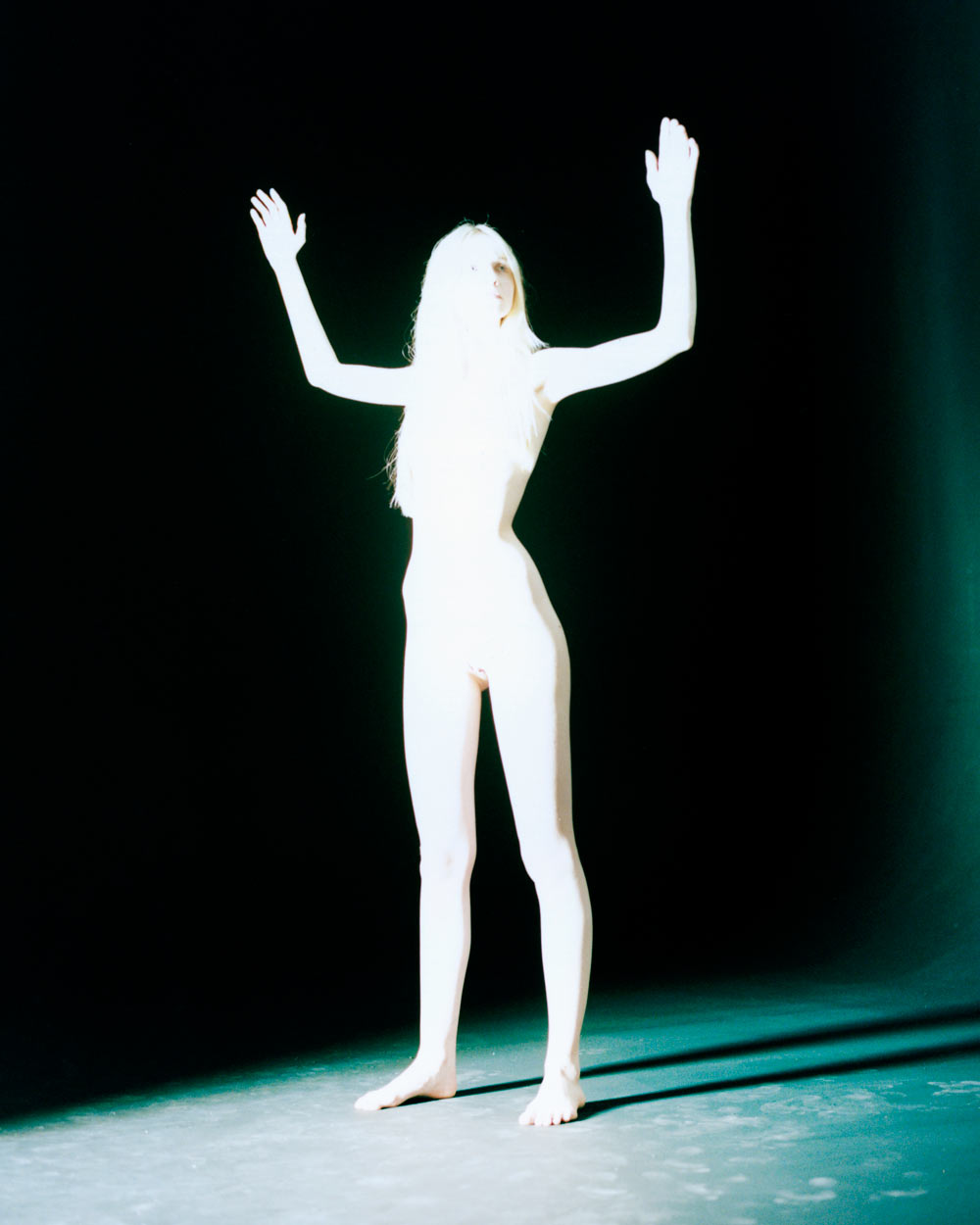

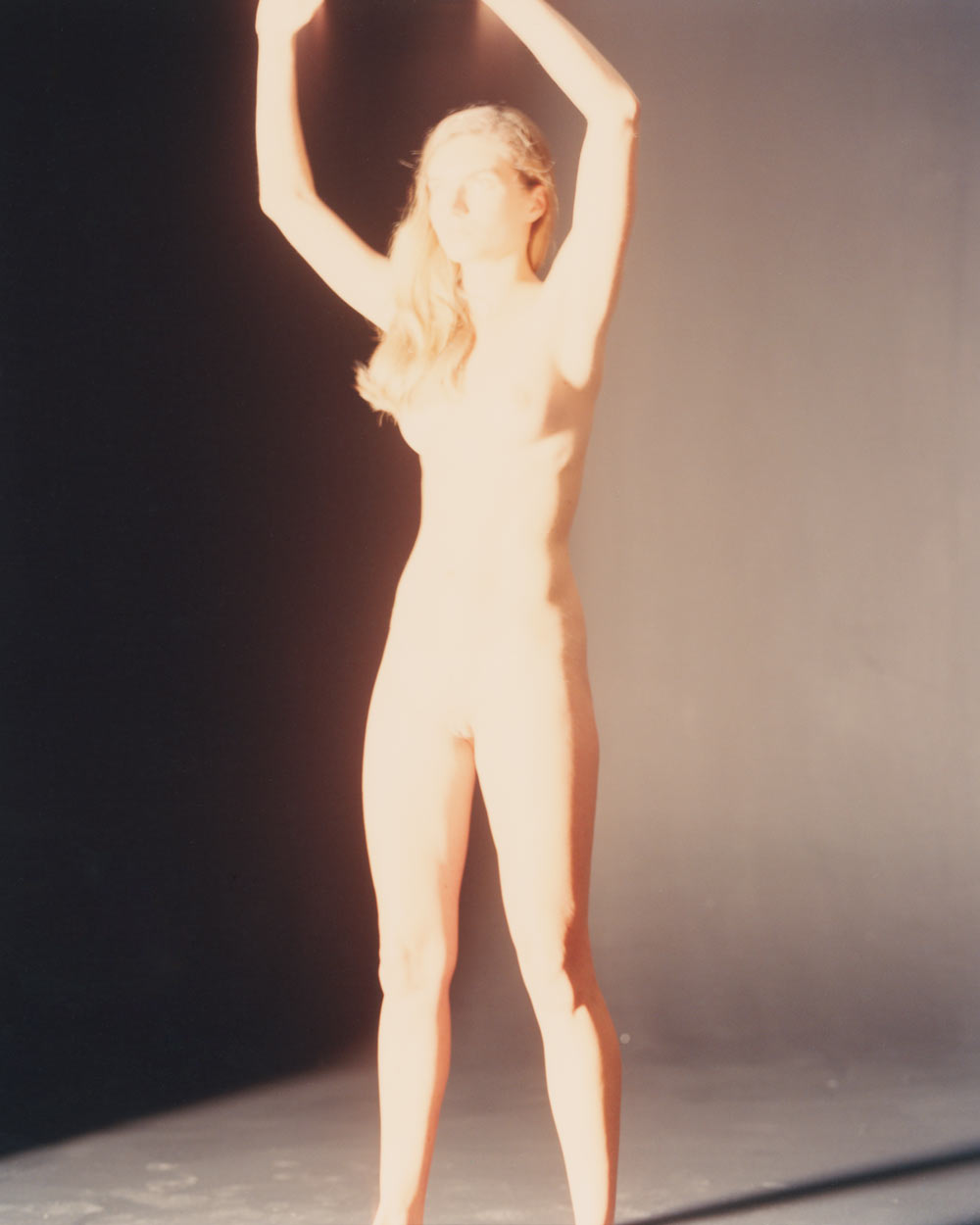

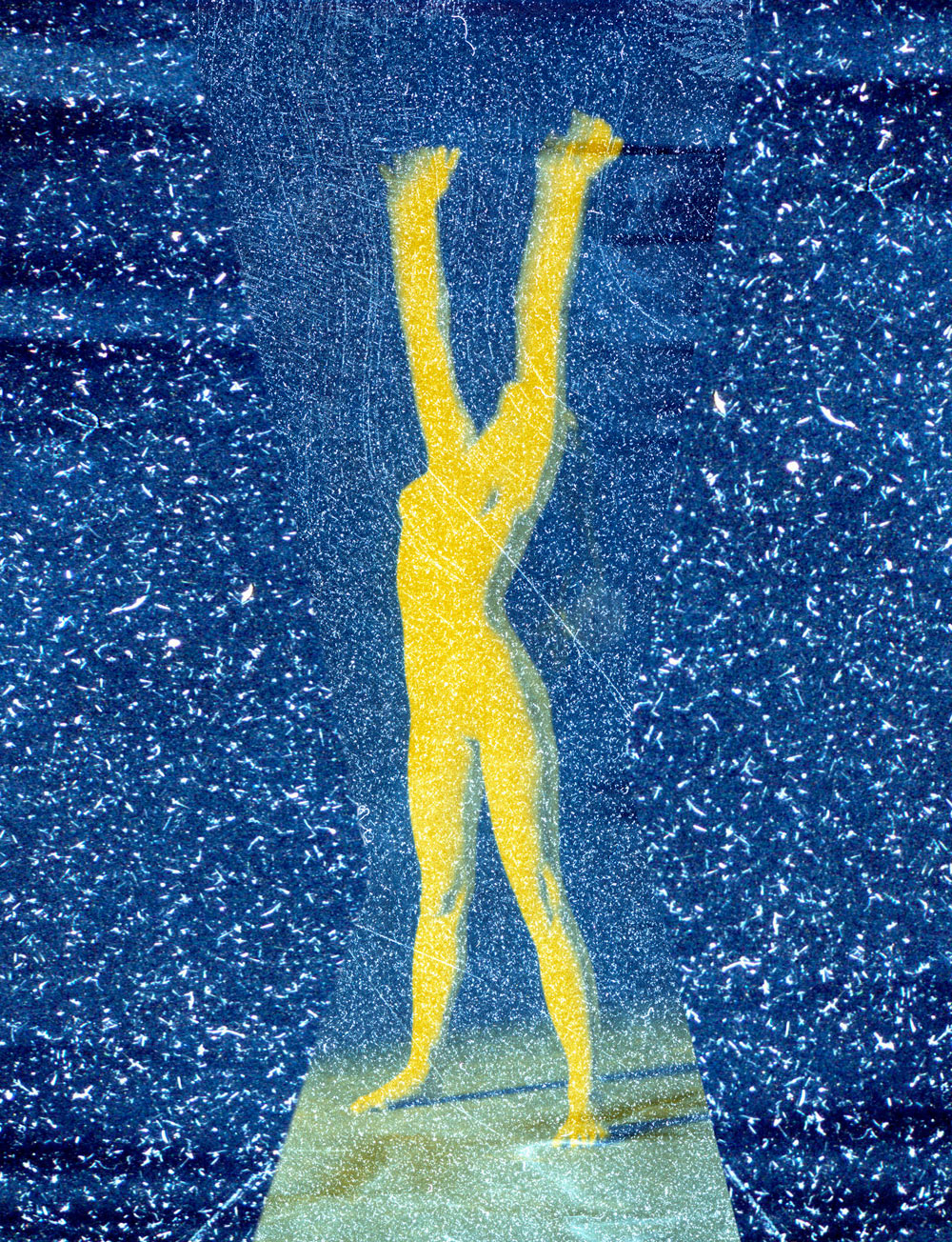

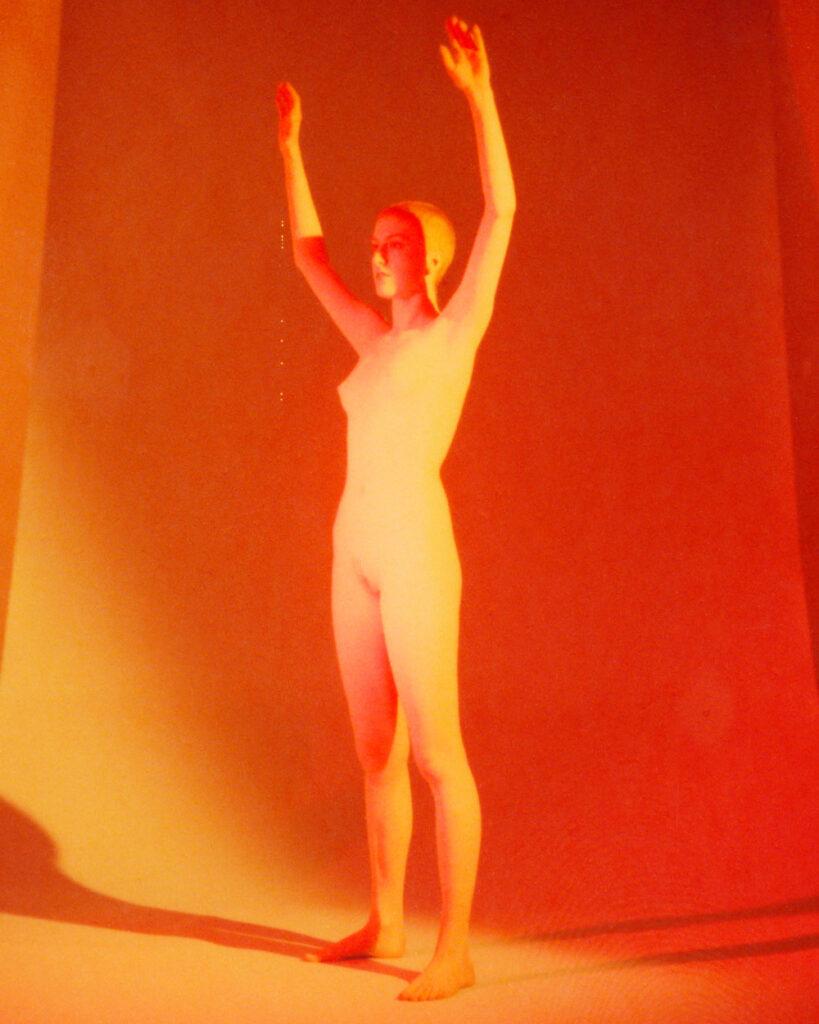

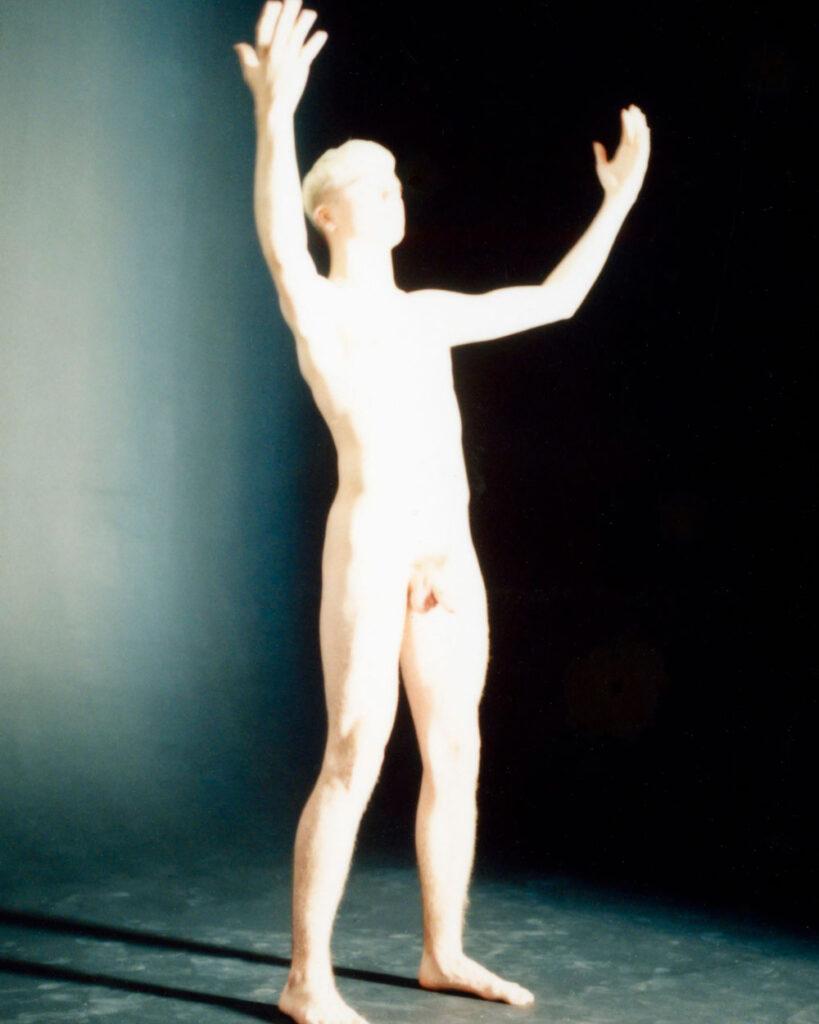

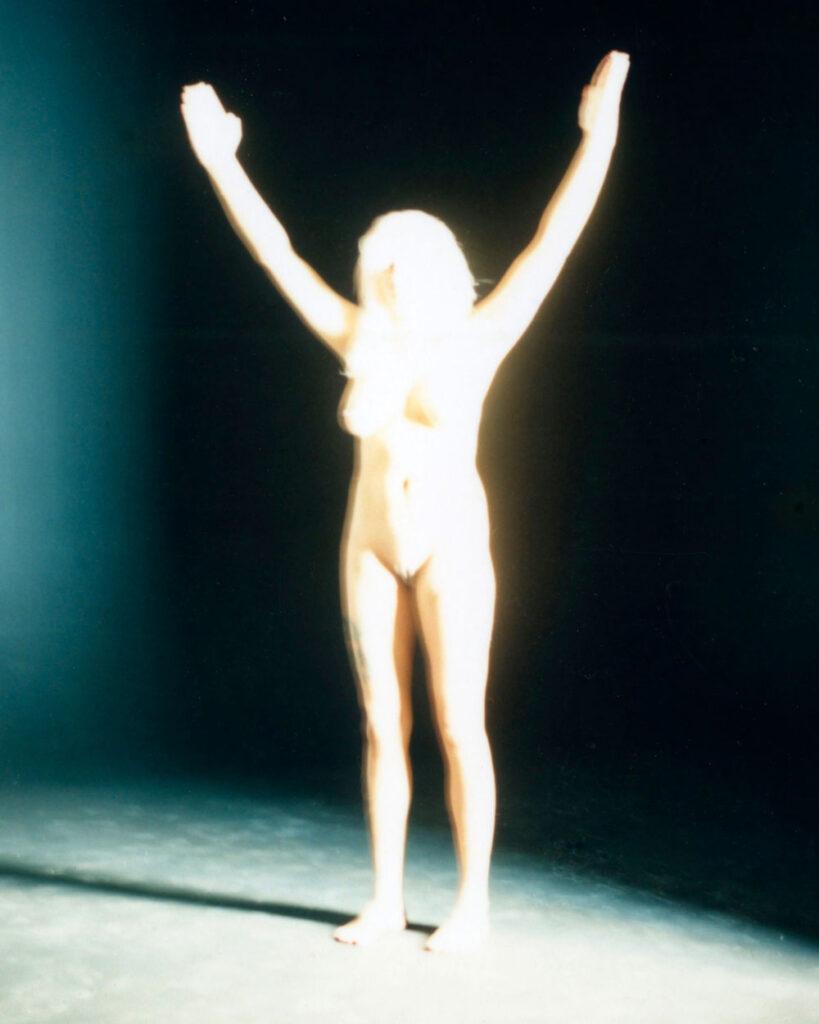

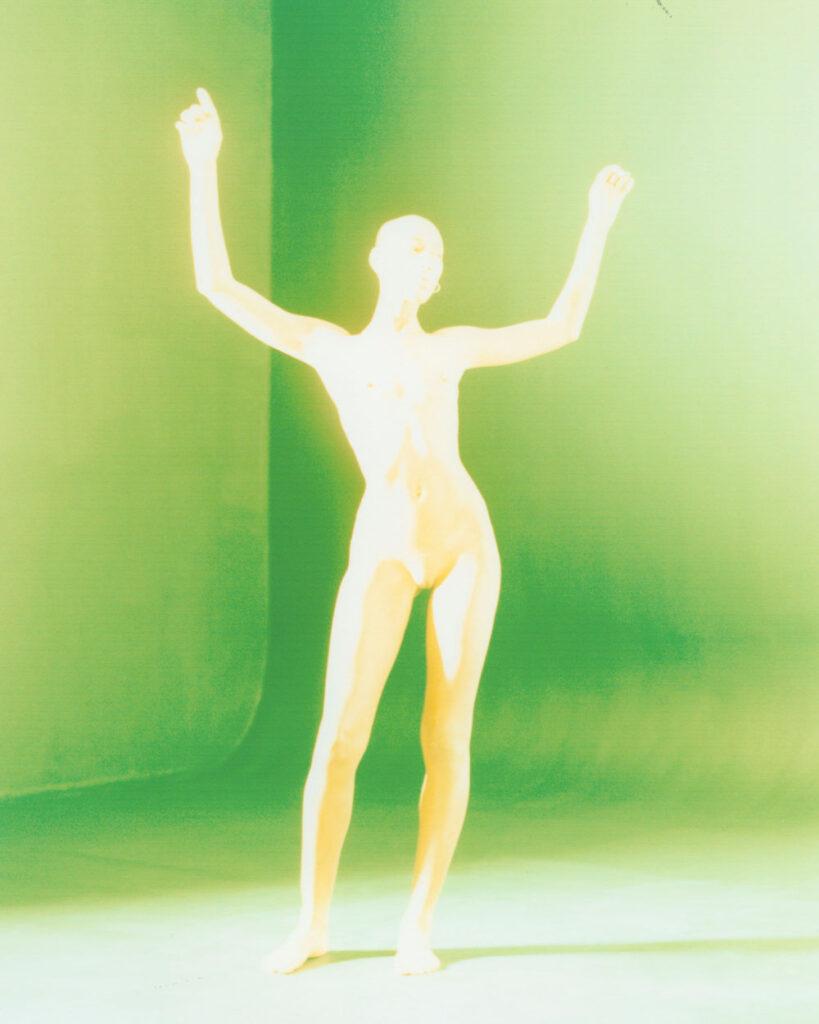

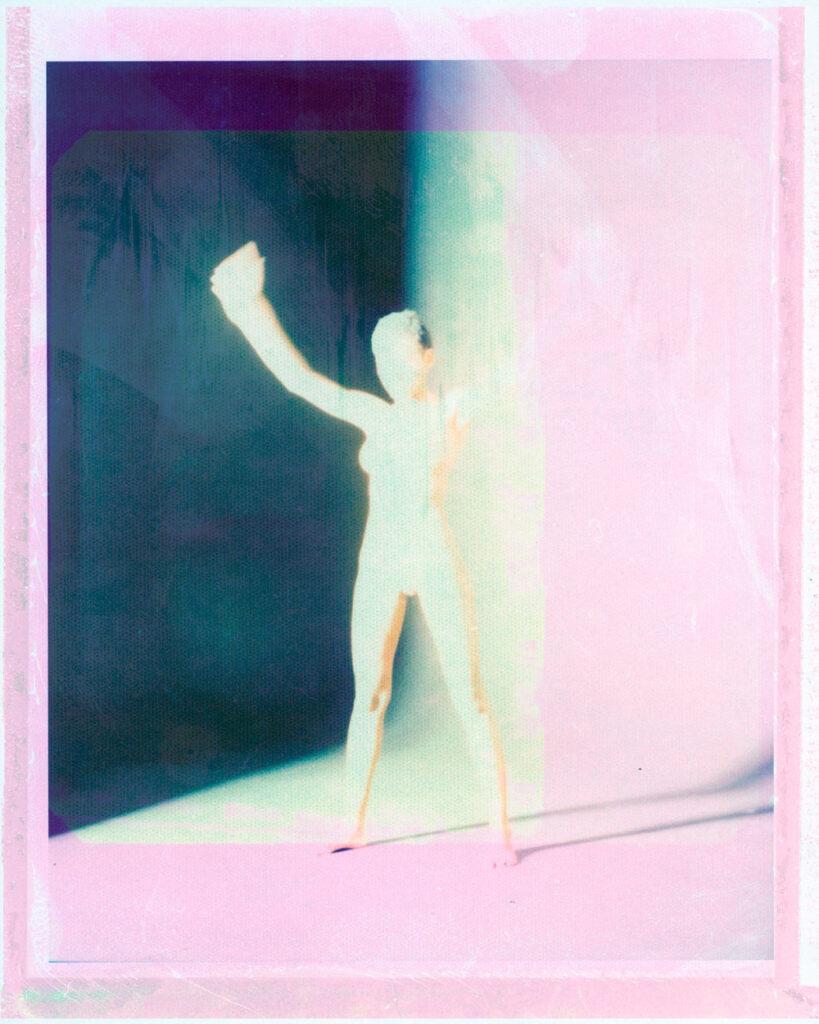

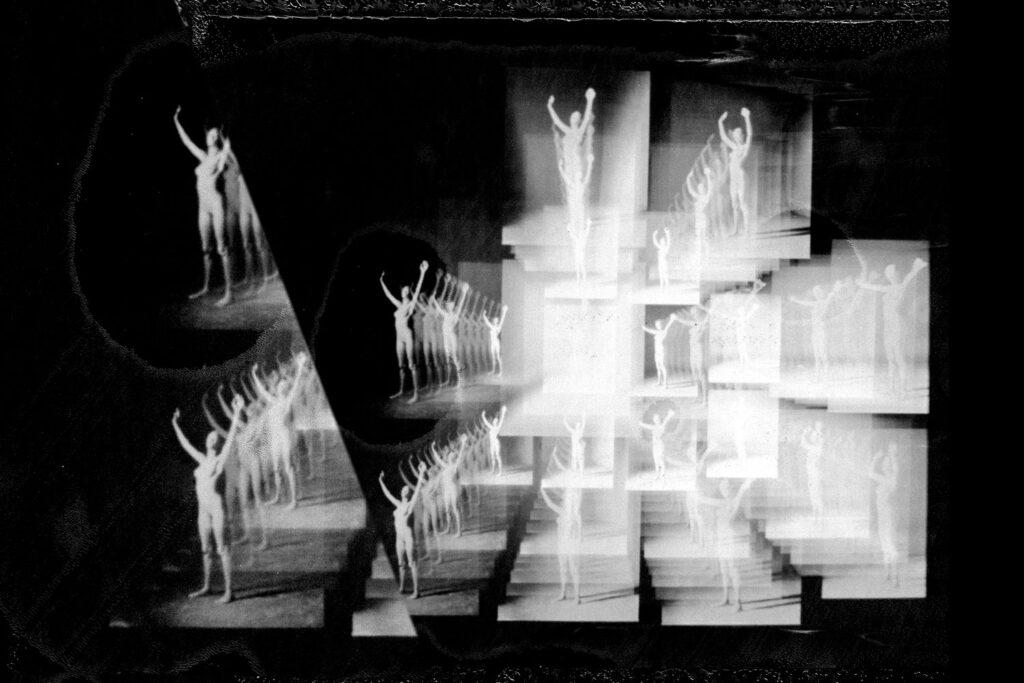

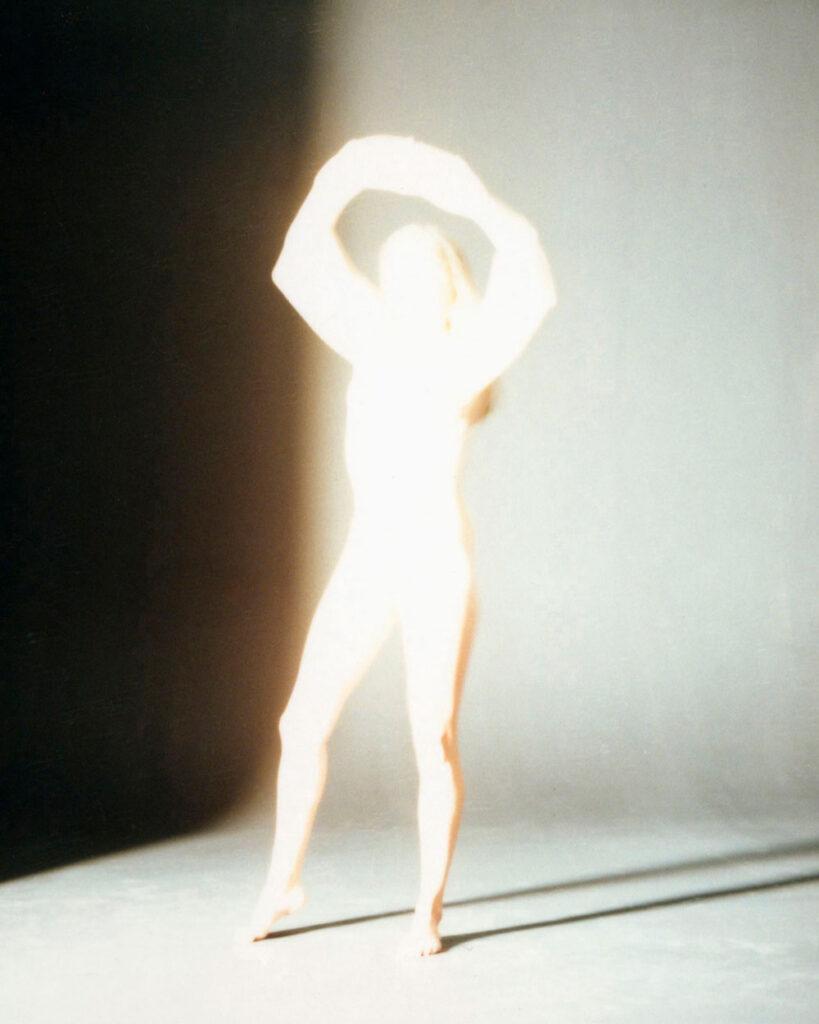

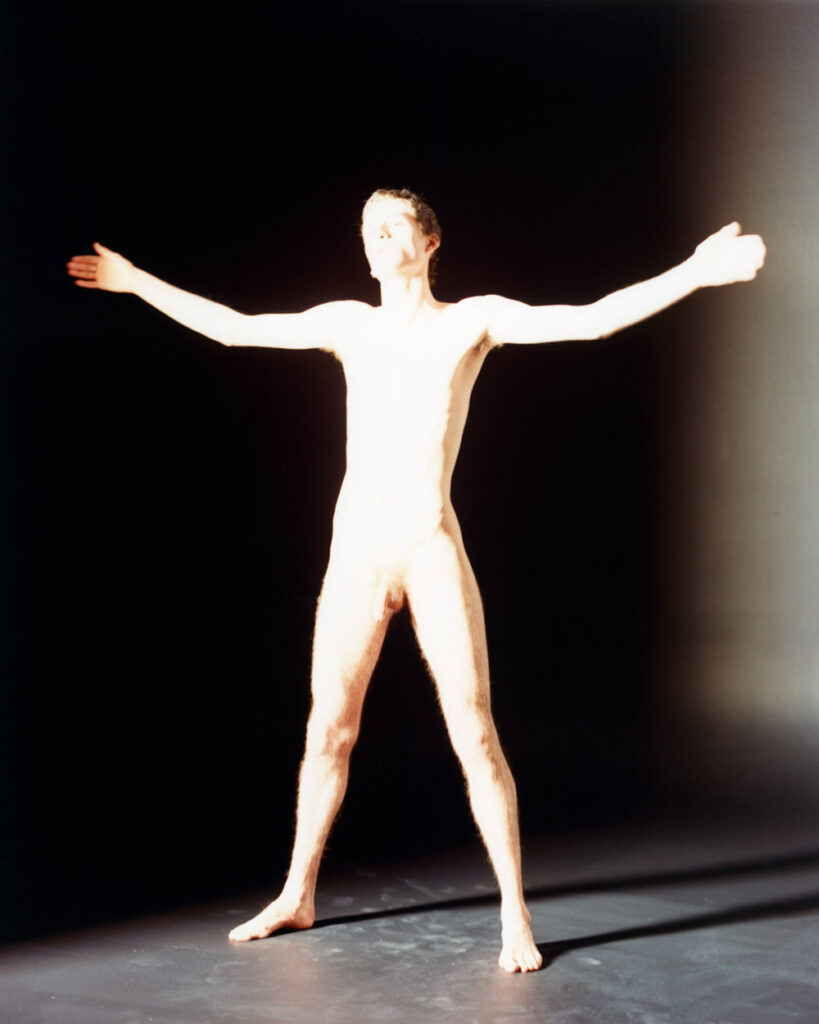

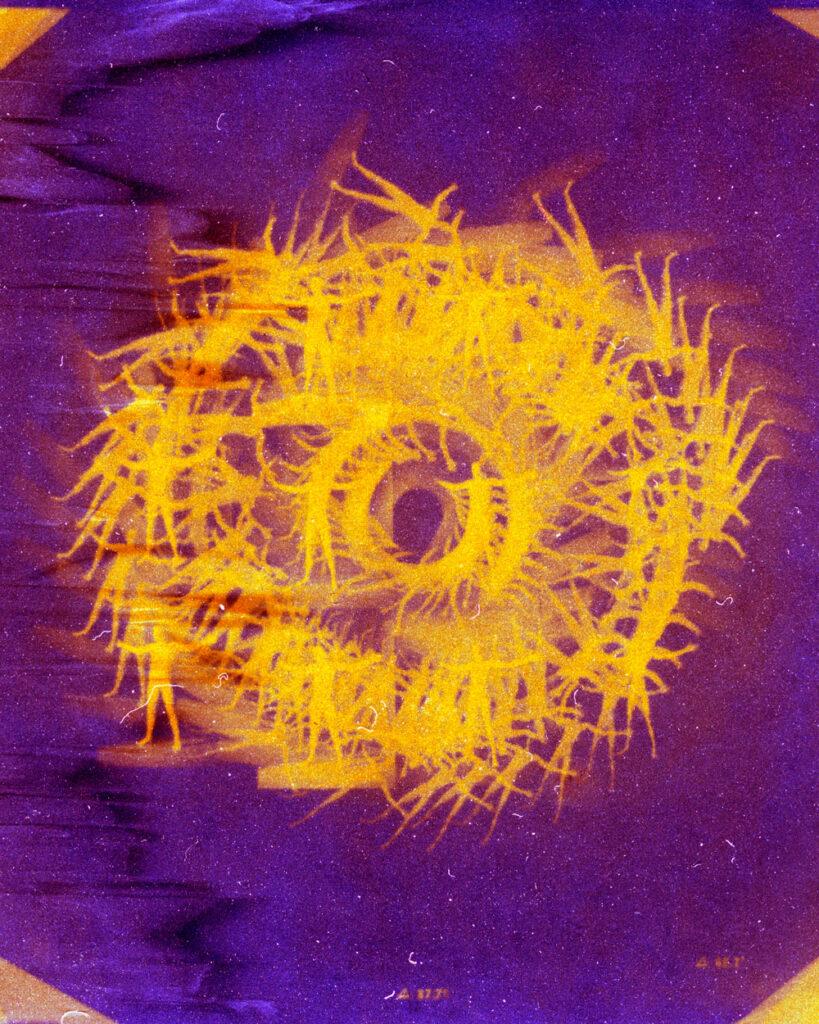

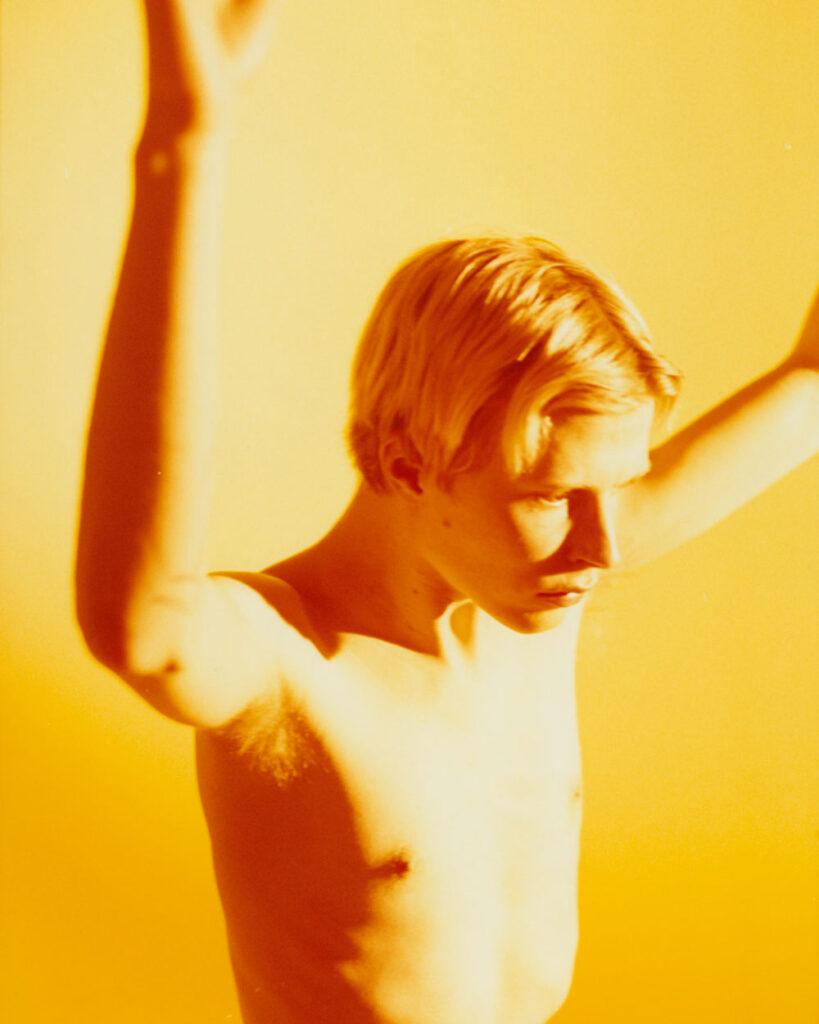

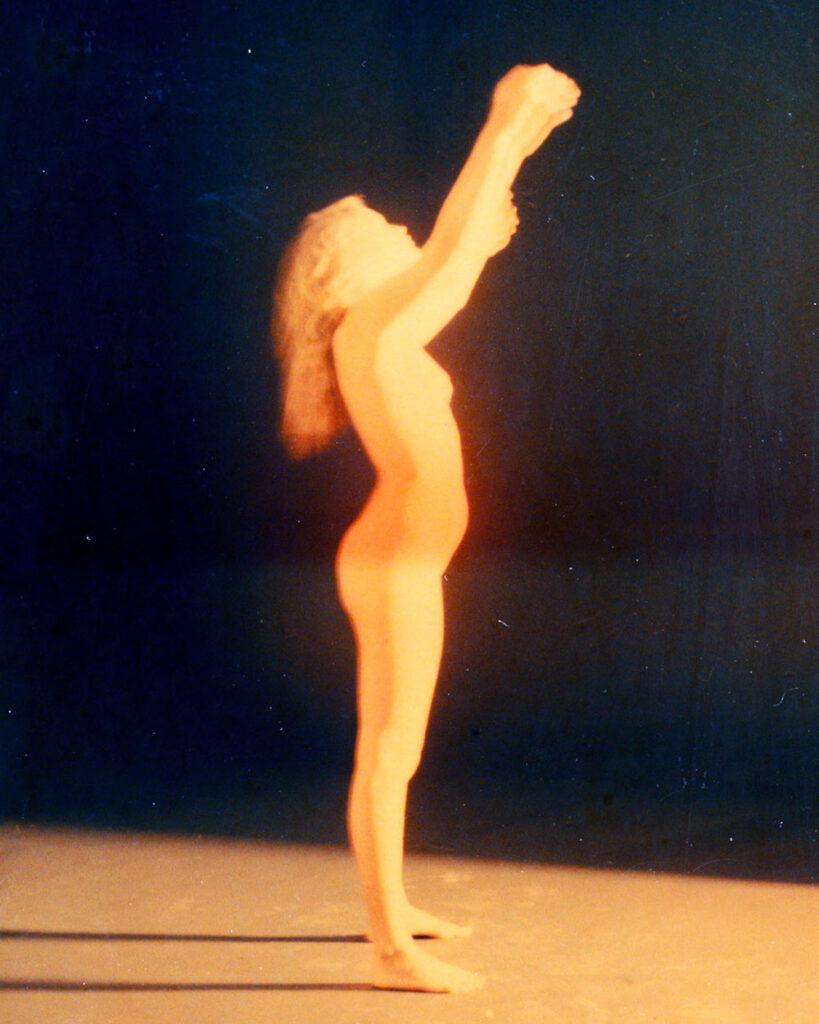

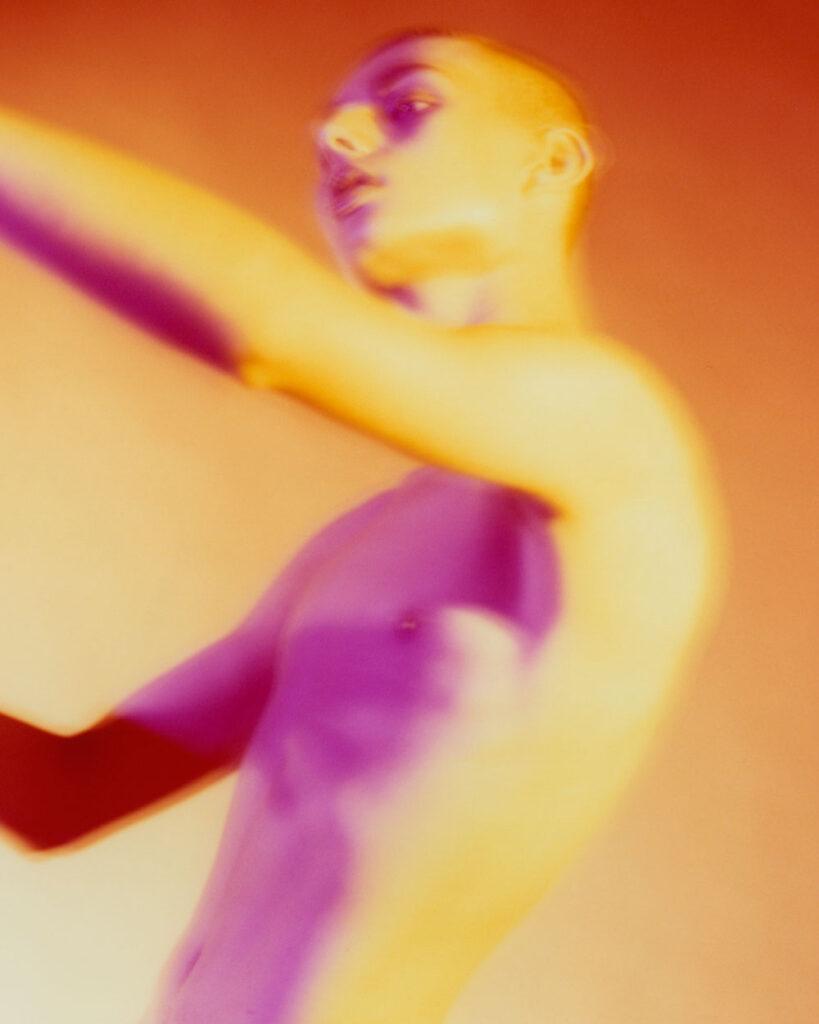

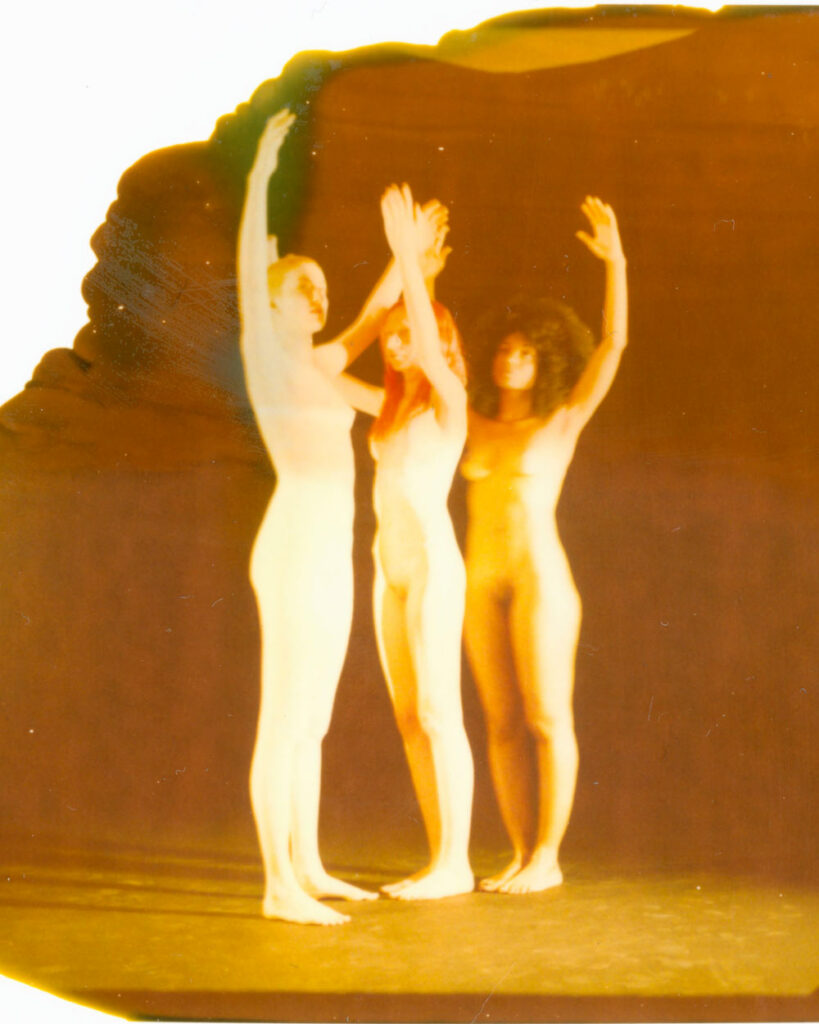

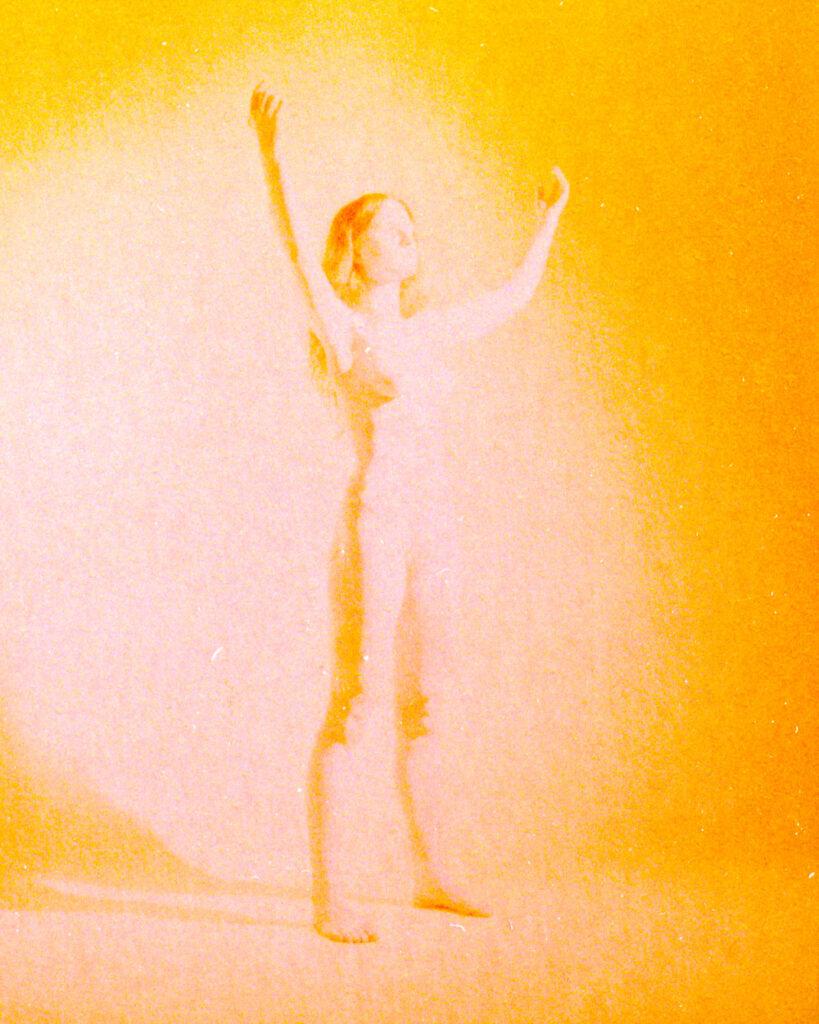

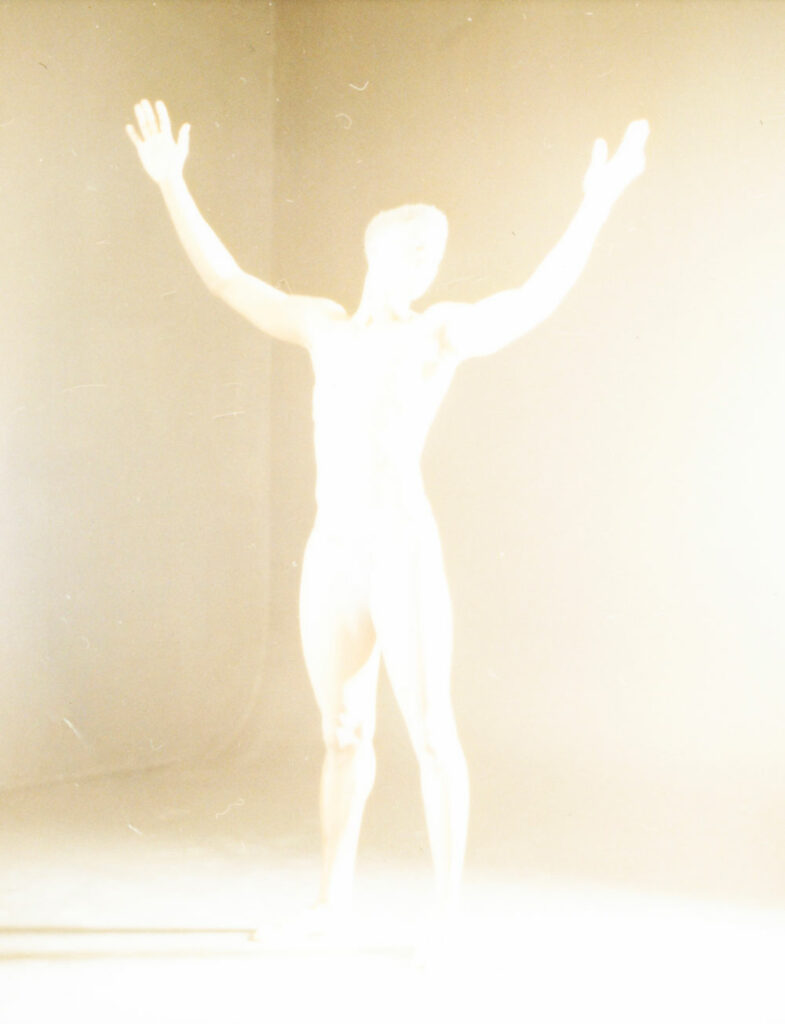

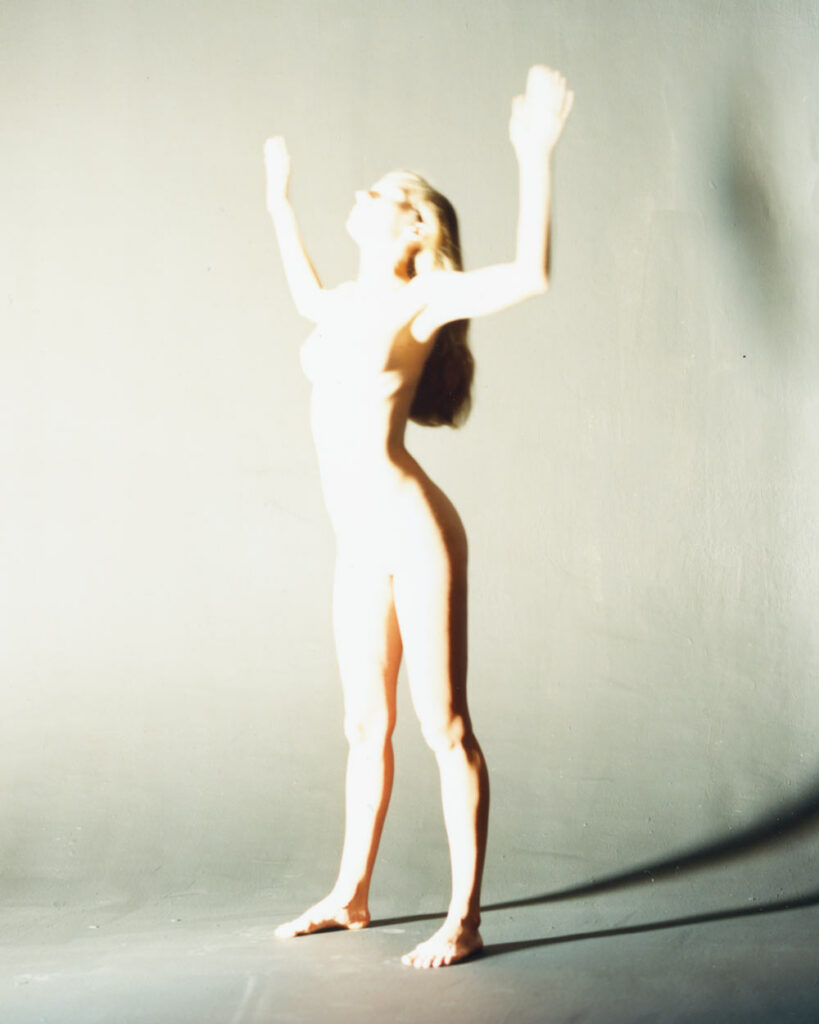

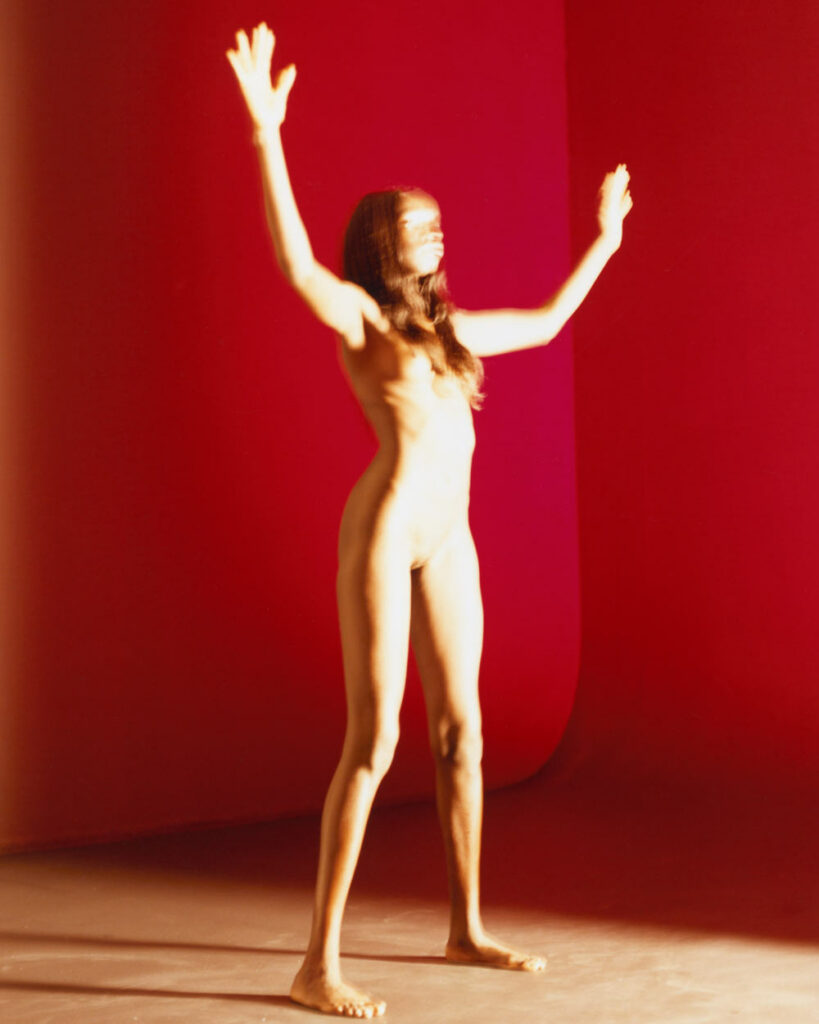

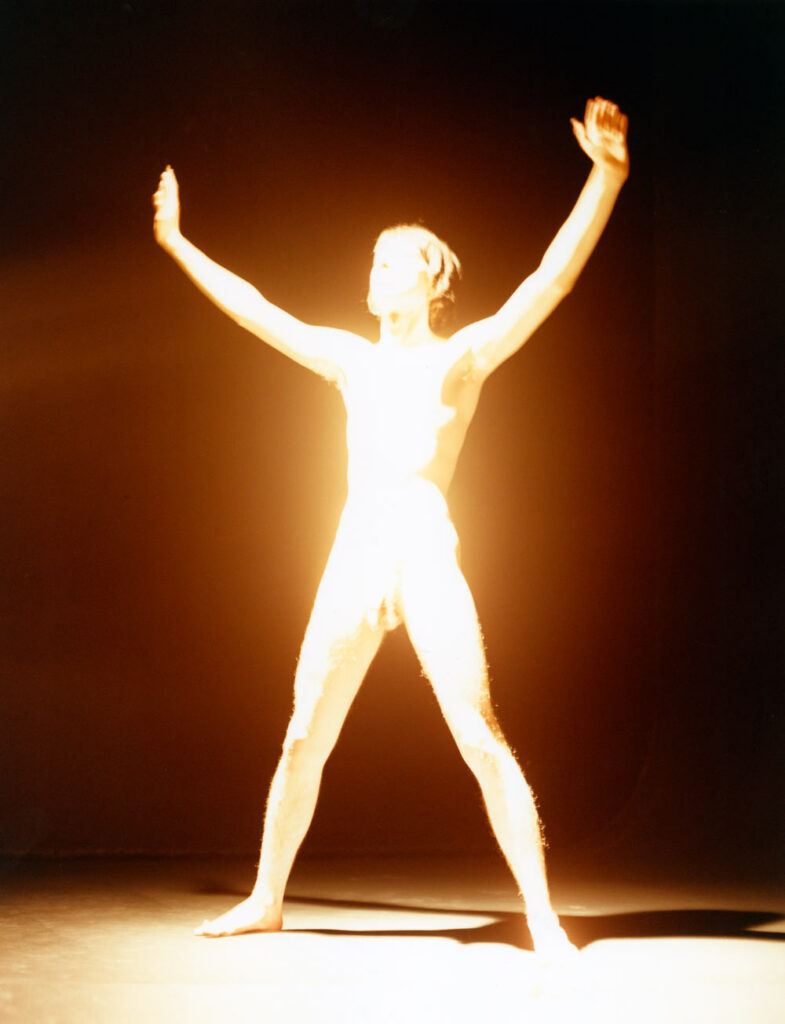

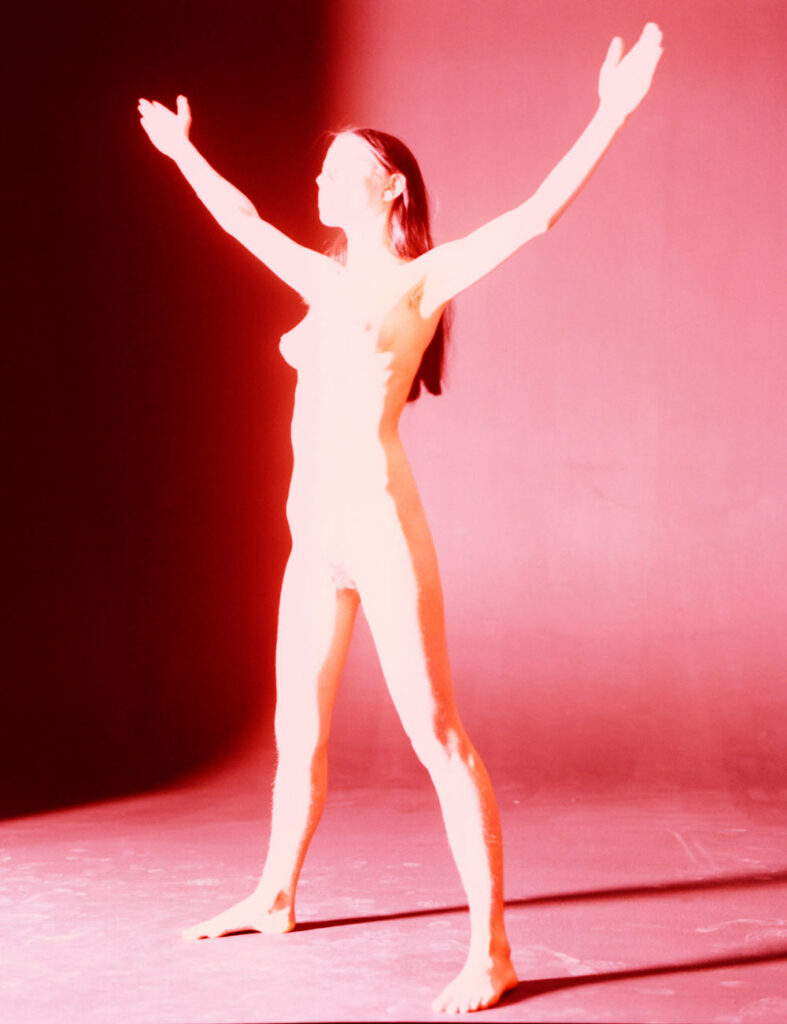

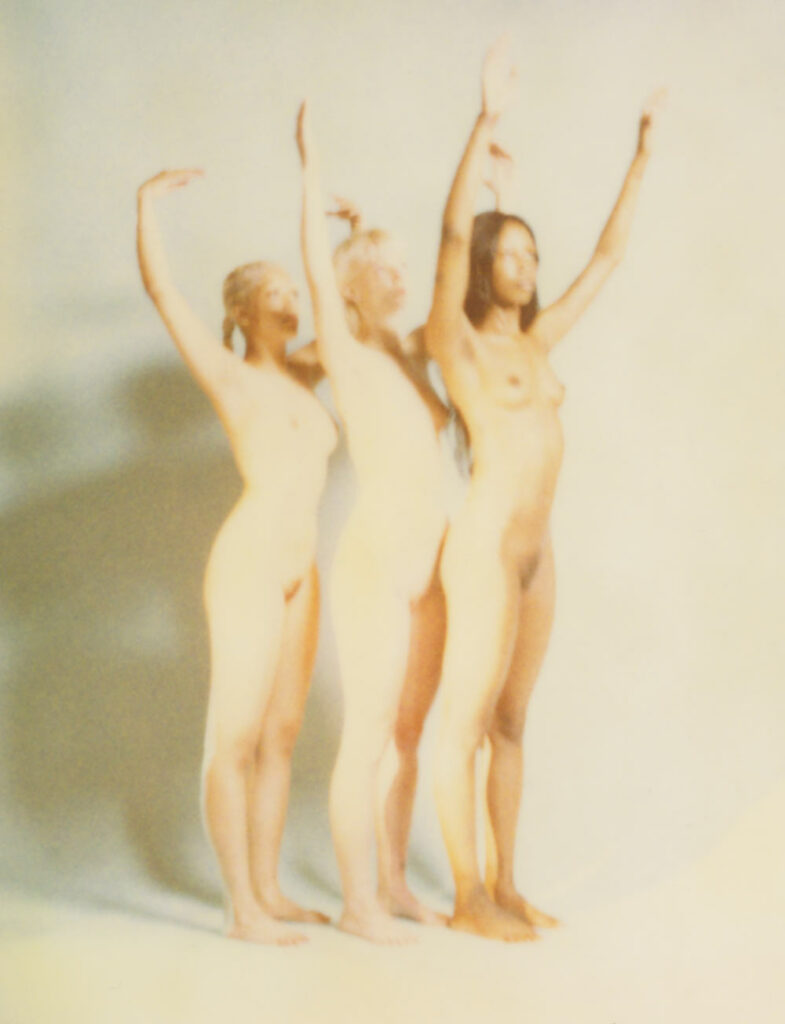

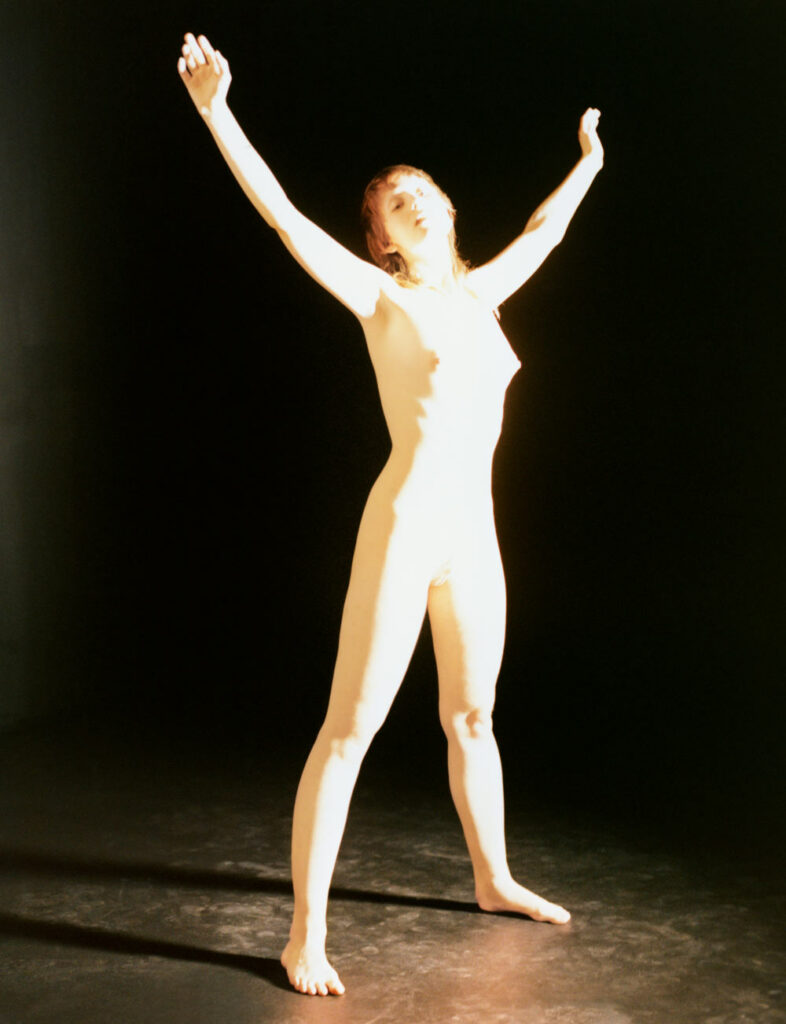

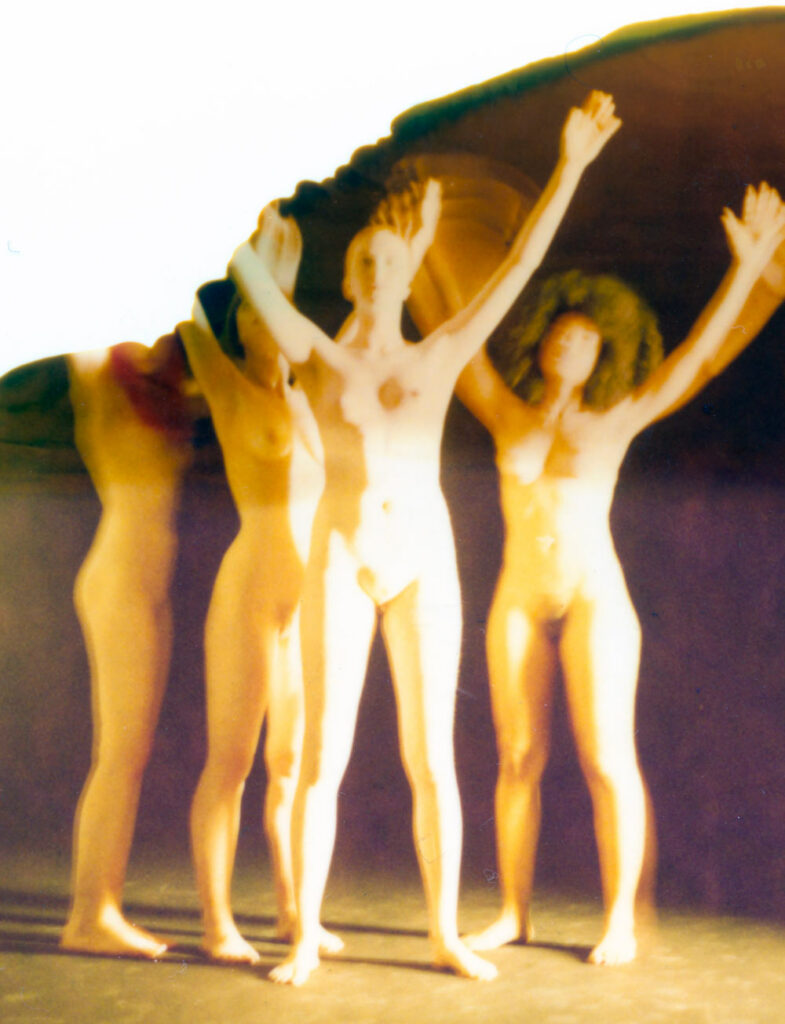

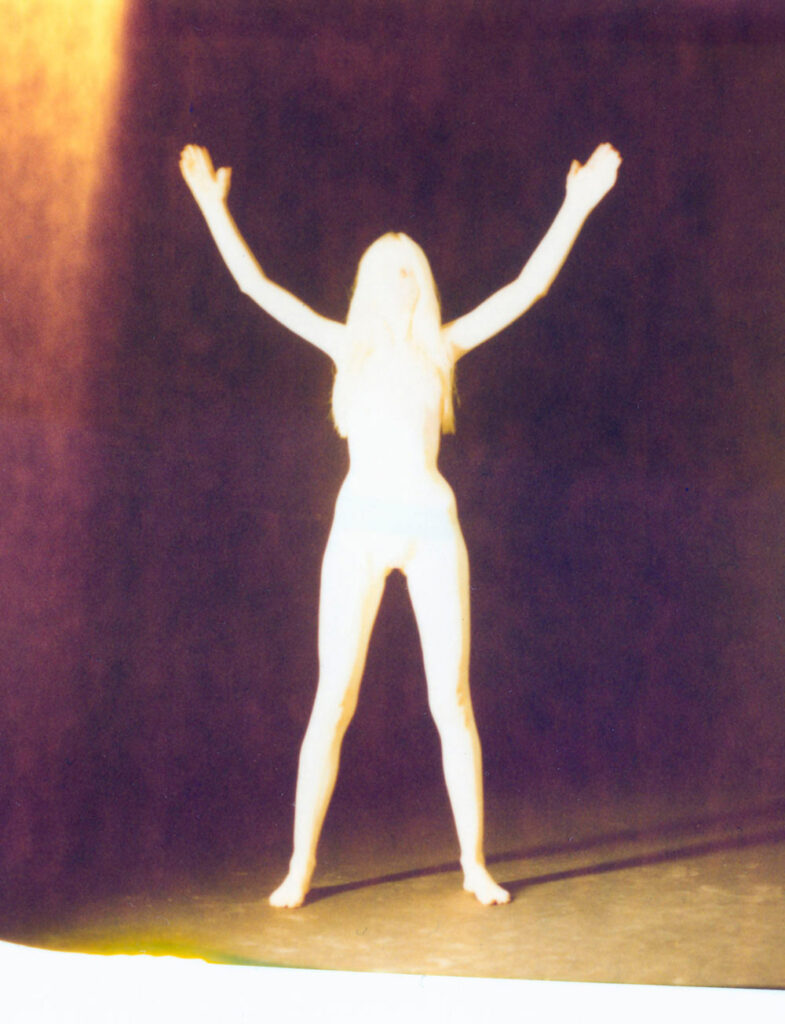

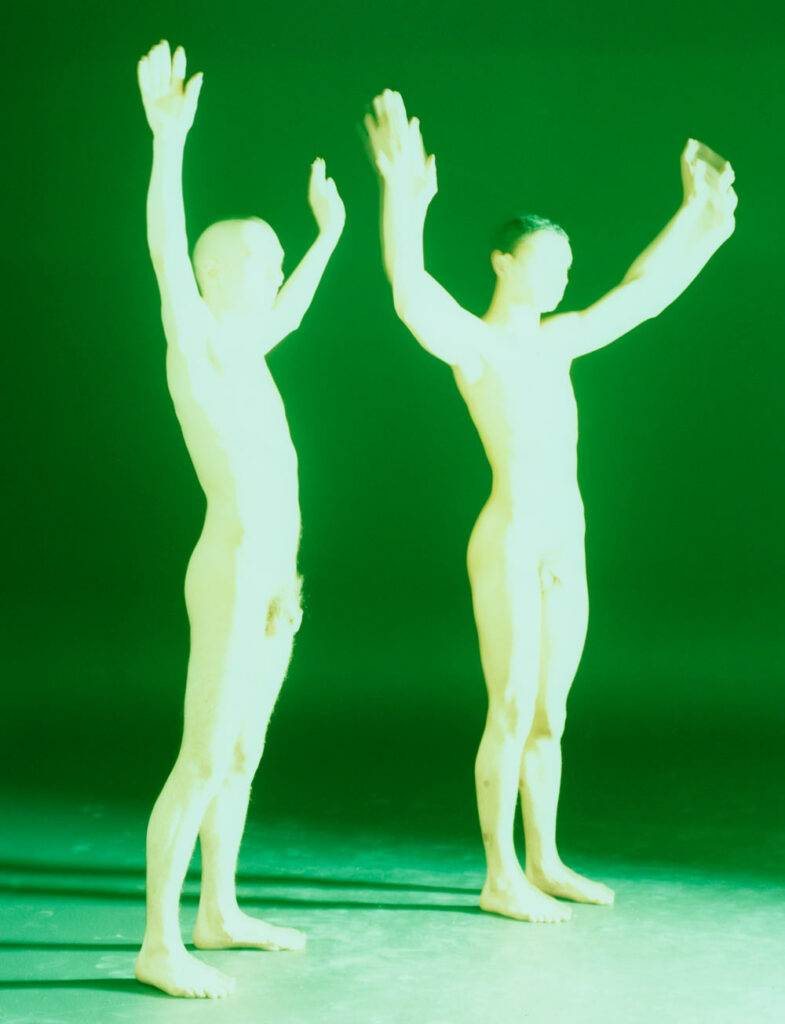

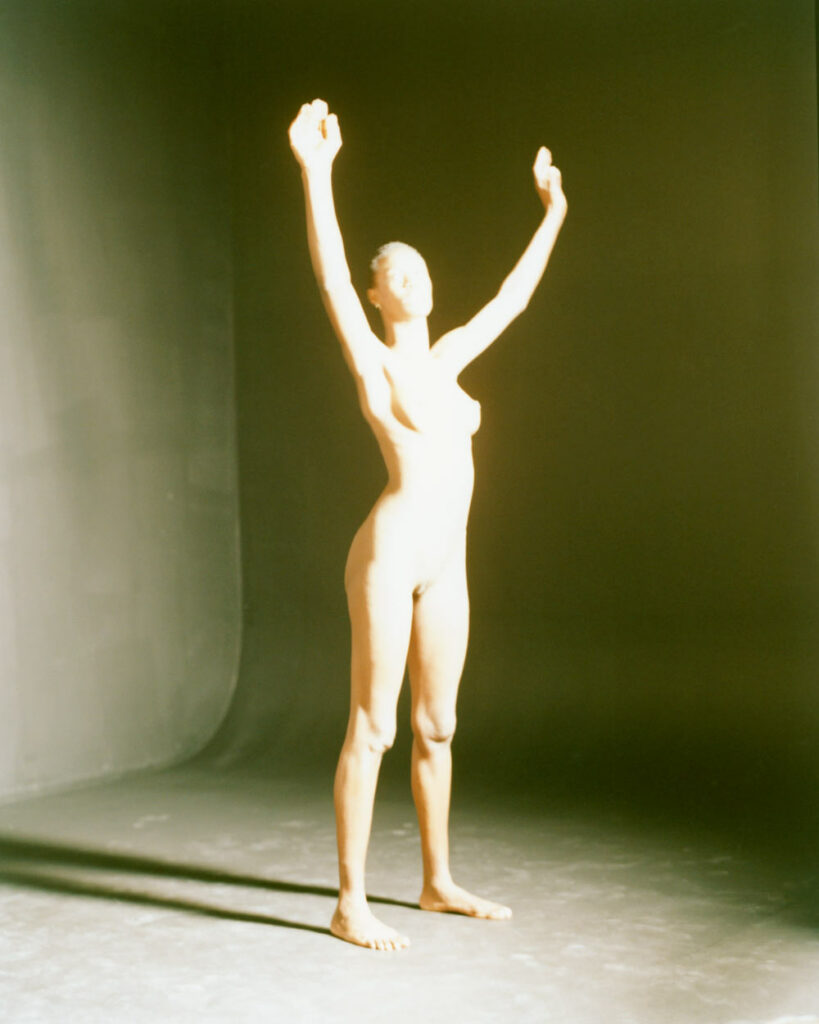

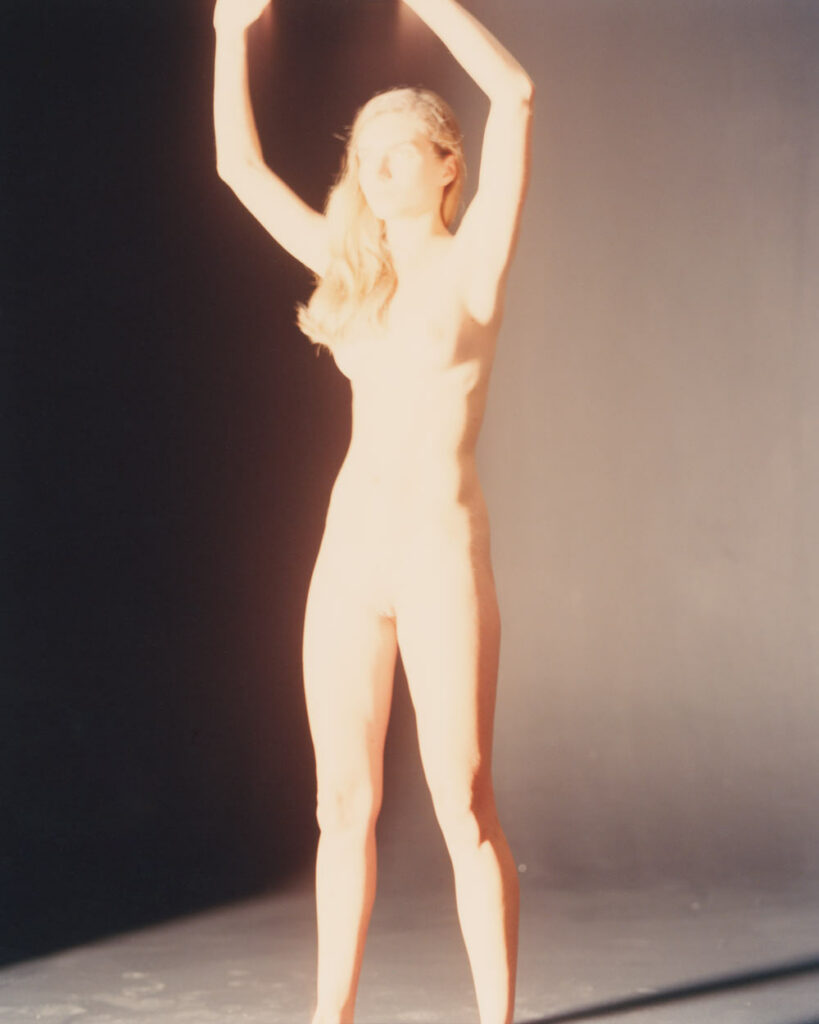

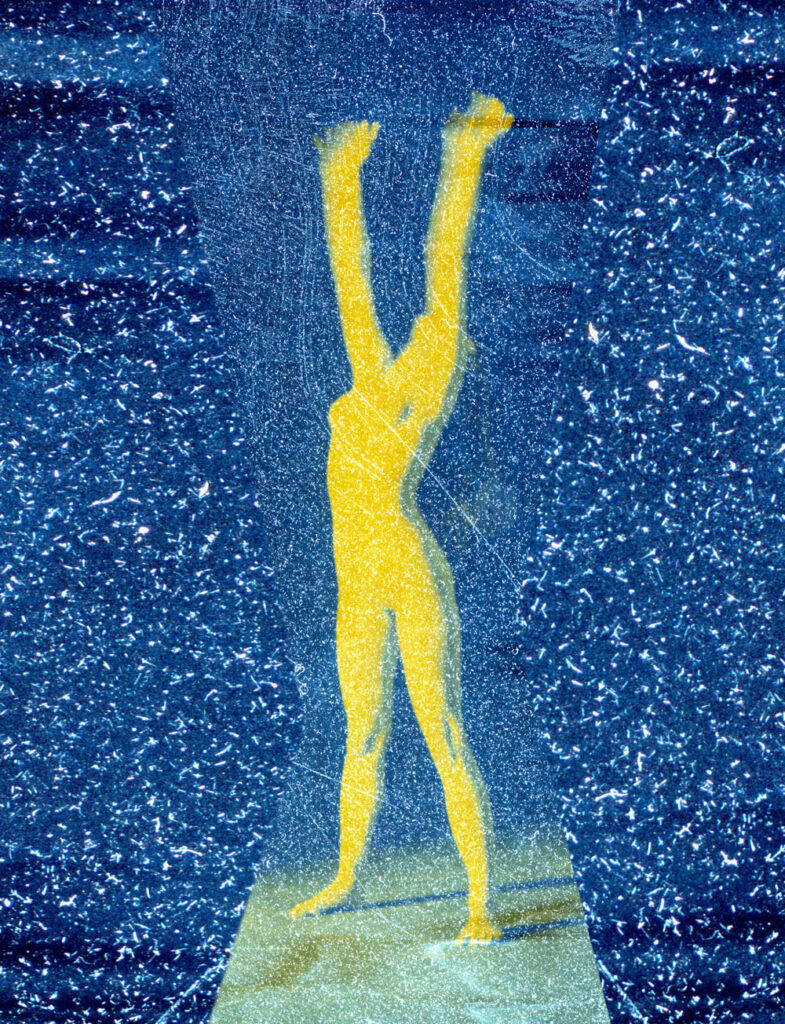

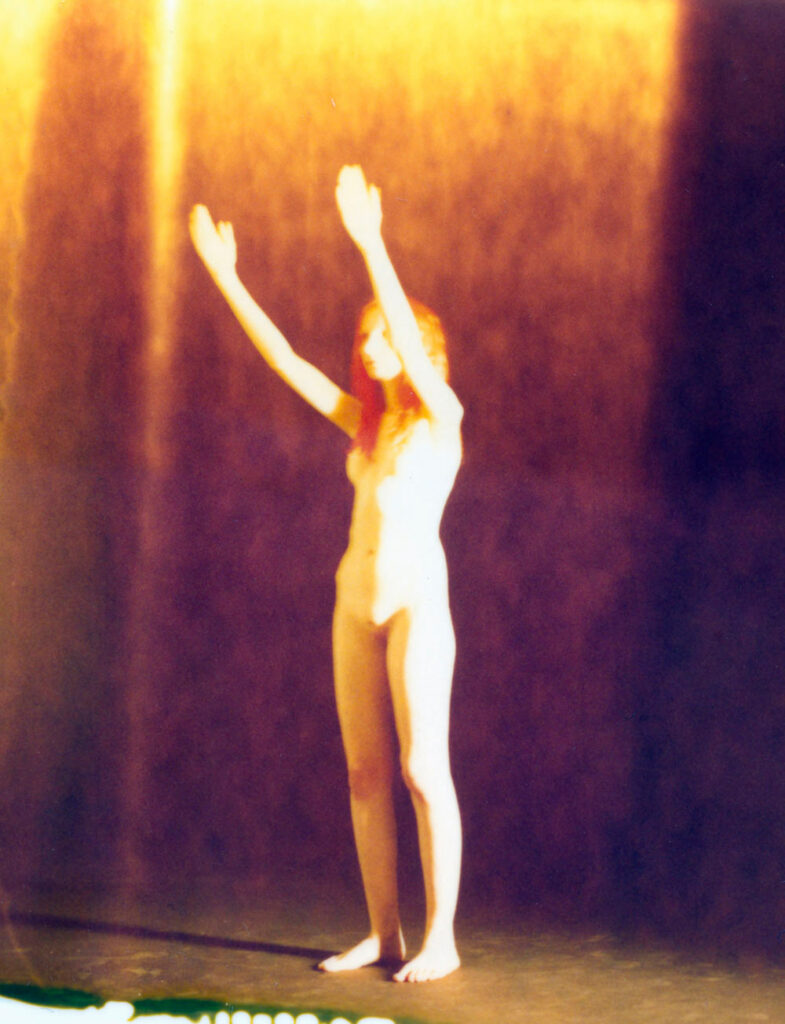

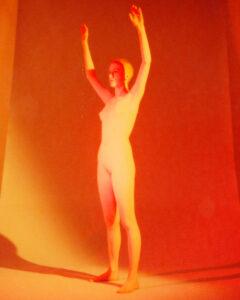

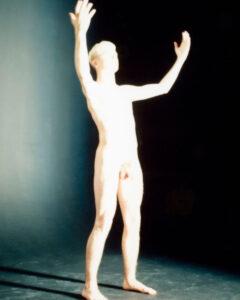

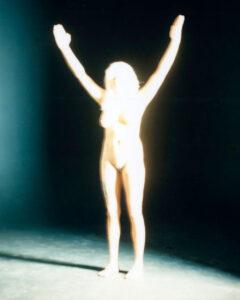

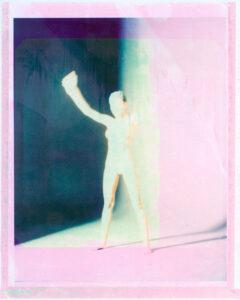

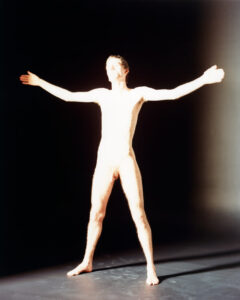

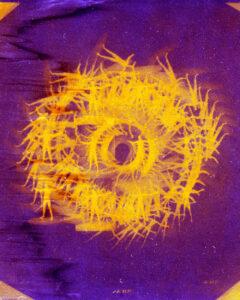

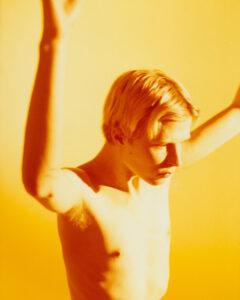

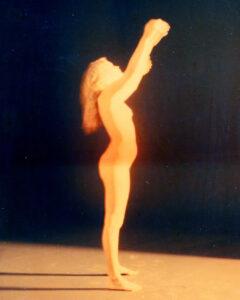

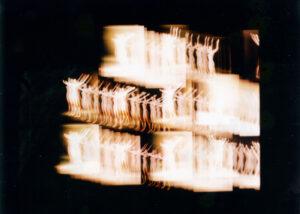

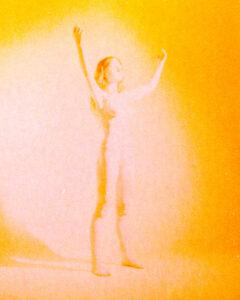

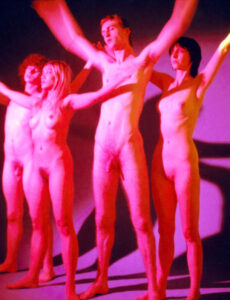

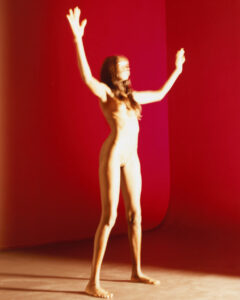

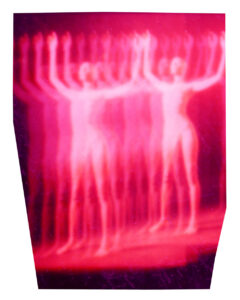

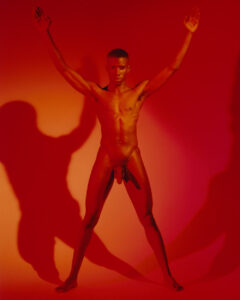

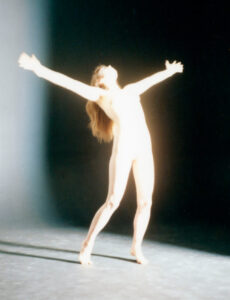

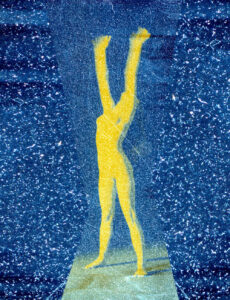

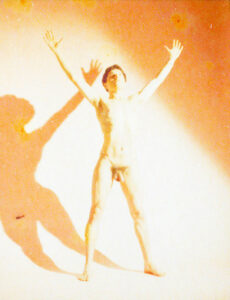

Gareth McConnell’s recent projects are essays in youthful bodies, saturated colors, and floral forms. They resemble stills from a cult initiation ceremony, a psychedelic clinical trial, or a nudist photography club. Their unexplained nature is countered by a calibrated use of color, as if shade and tint, not form, unlock their meaning. McConnell’s handling of color pursues the hue of rave music culture as the distillation of late twentieth century youth counterculture. It grinds down all kinds of disparate imagery that captures the glittering tail of burning brightly and recalls the phosphorescent smears of disco lights across bodies. McConnell’s work recaptures the flashes of Dave Swindells’s snapshots from 1990s London nightclubs; the use of paused frames in Mark Leckey’s film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999); the intense color of Andy Bettles’s mid-1980s cross-process fashion editorials published in The Face magazine or Mark Lebon’s double-exposure portraits for i-D magazine at the same time; the Super-8 footage of Derek Jarman’s flower beds on Dungeness Beach filmed at night in The Garden (1990).

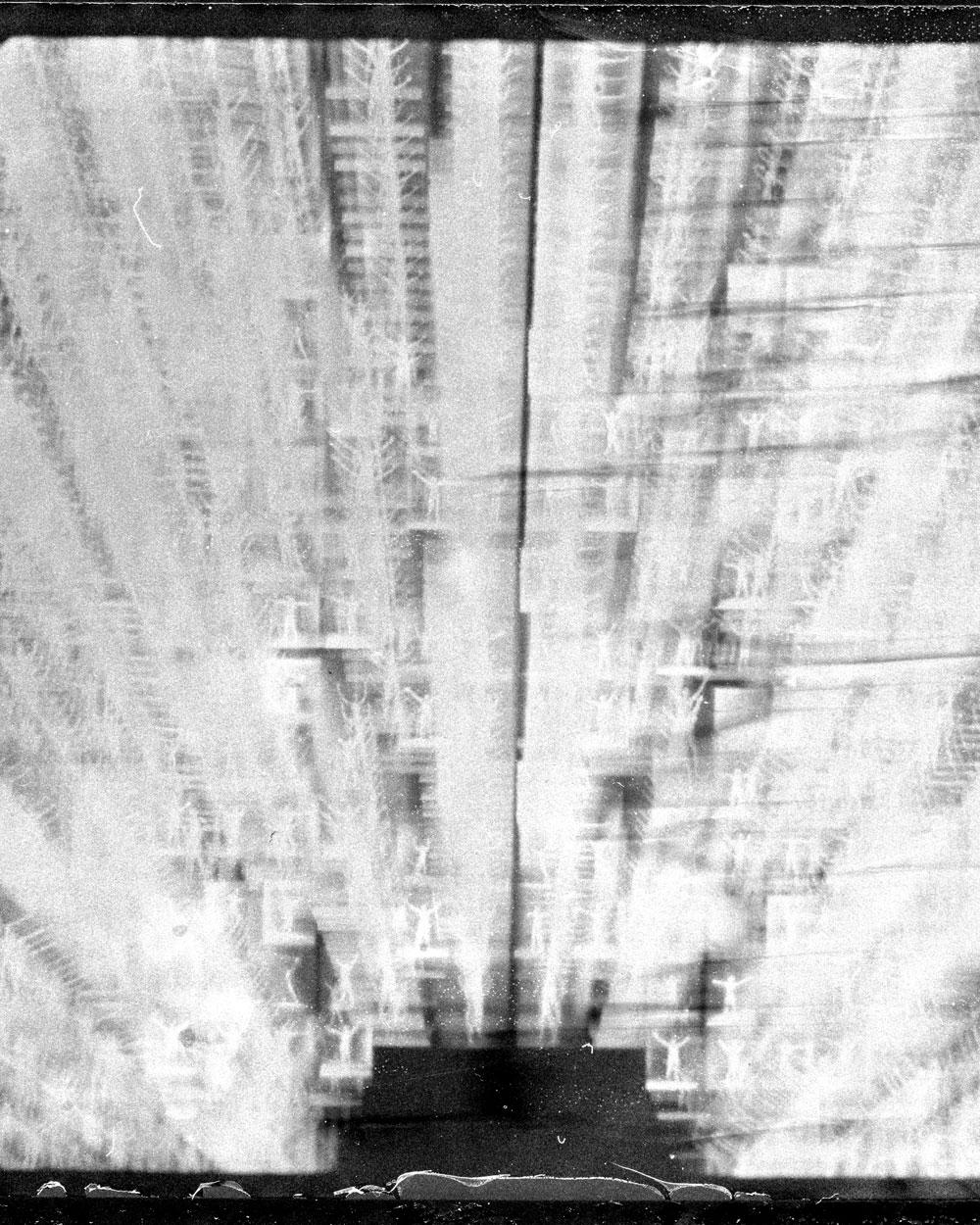

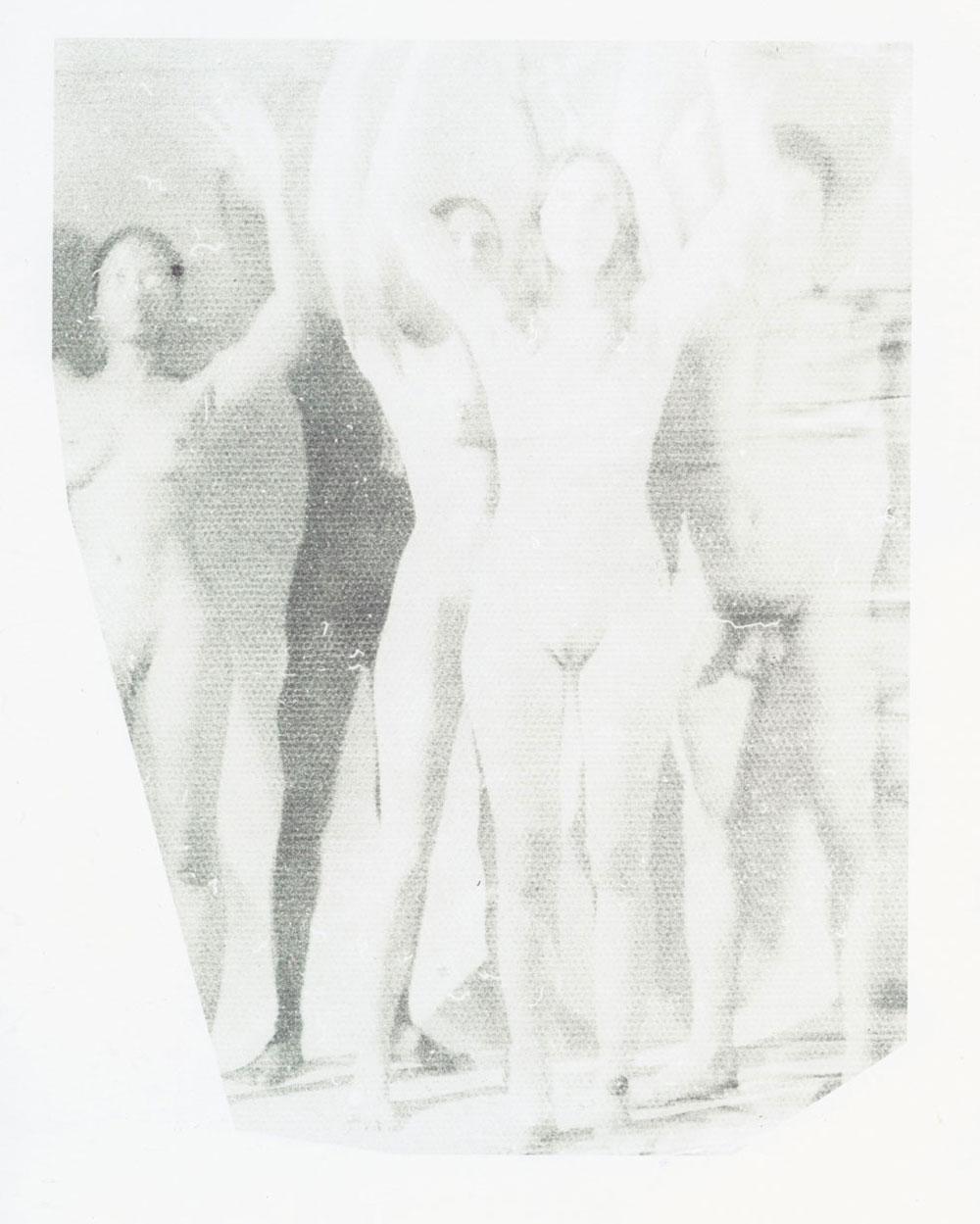

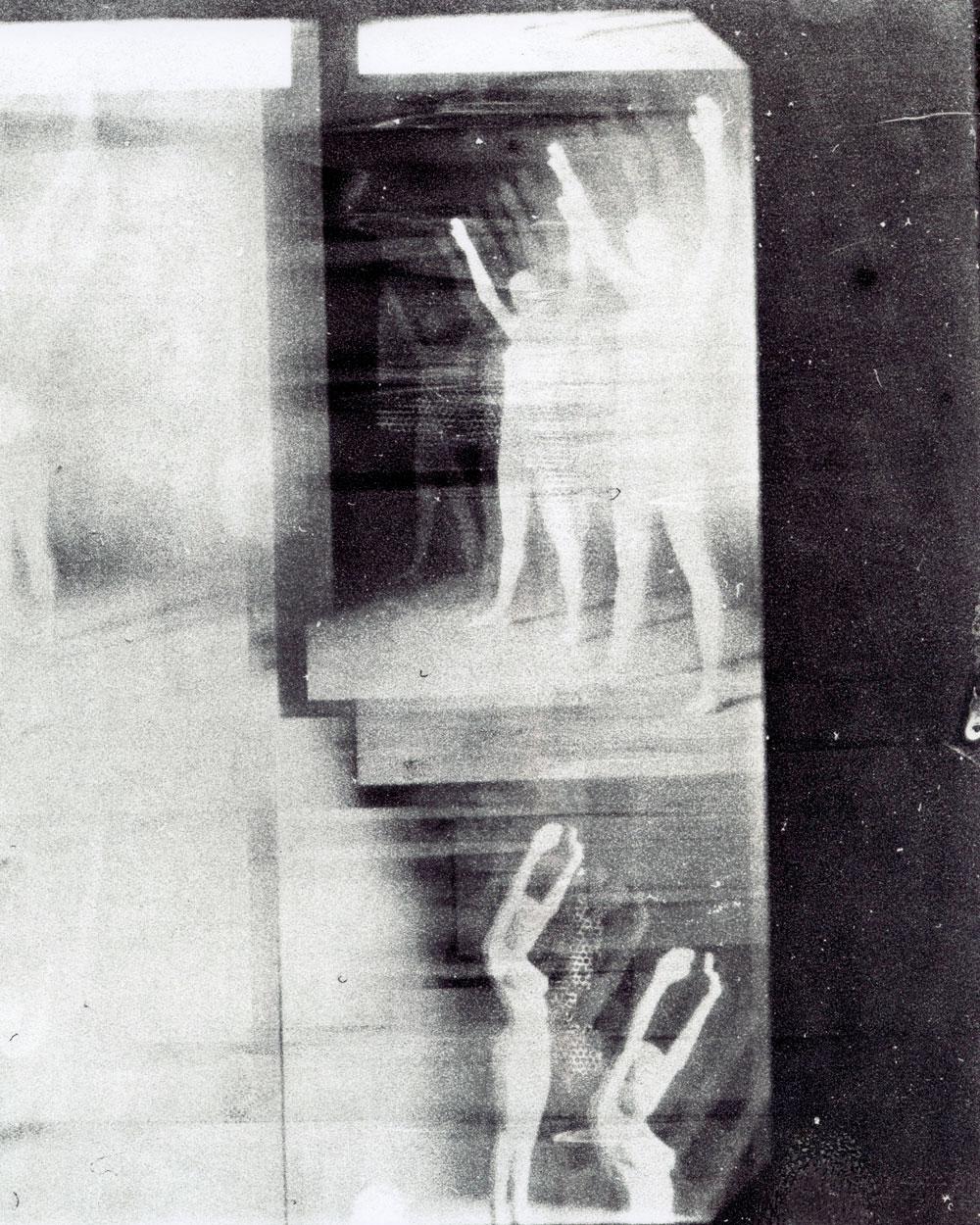

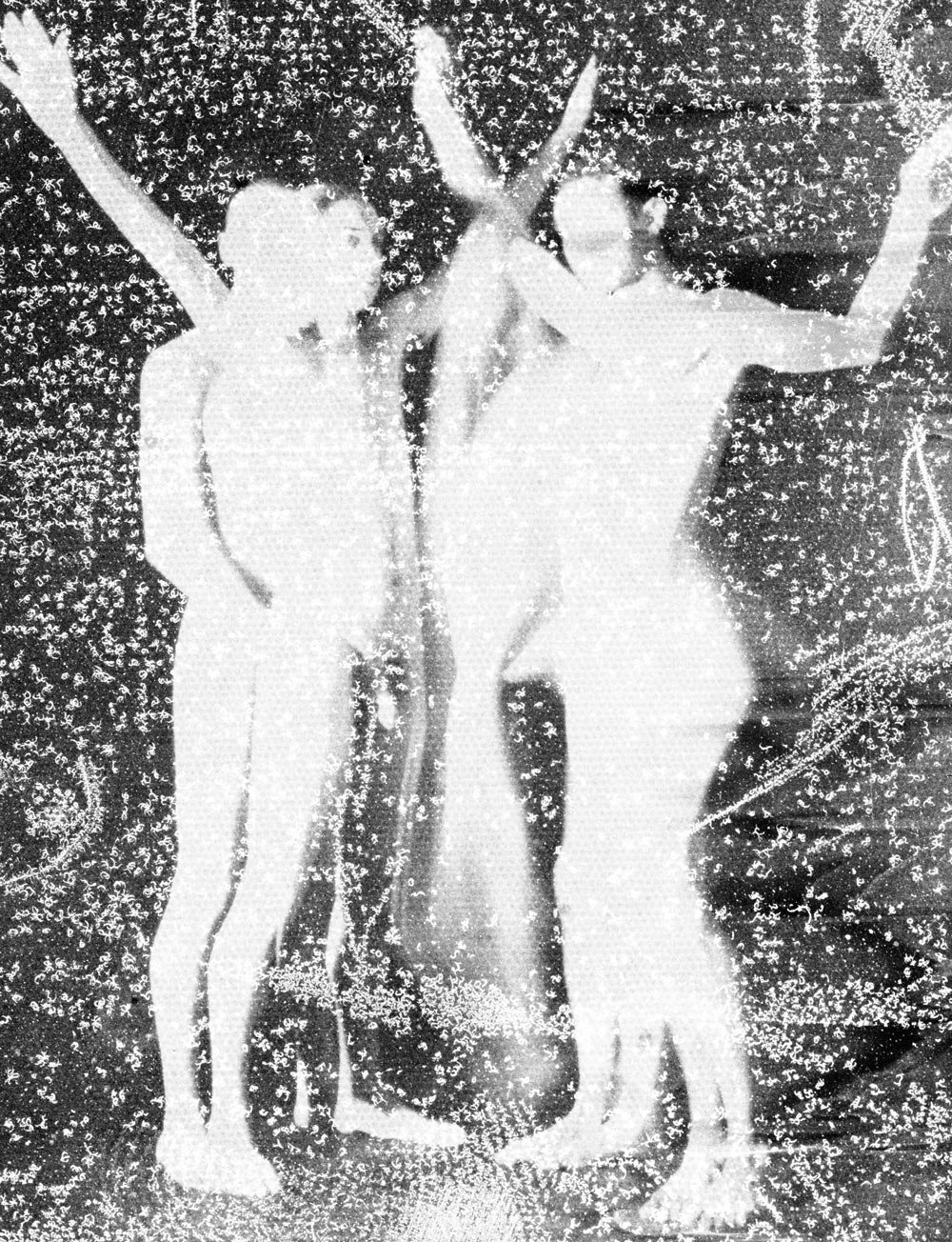

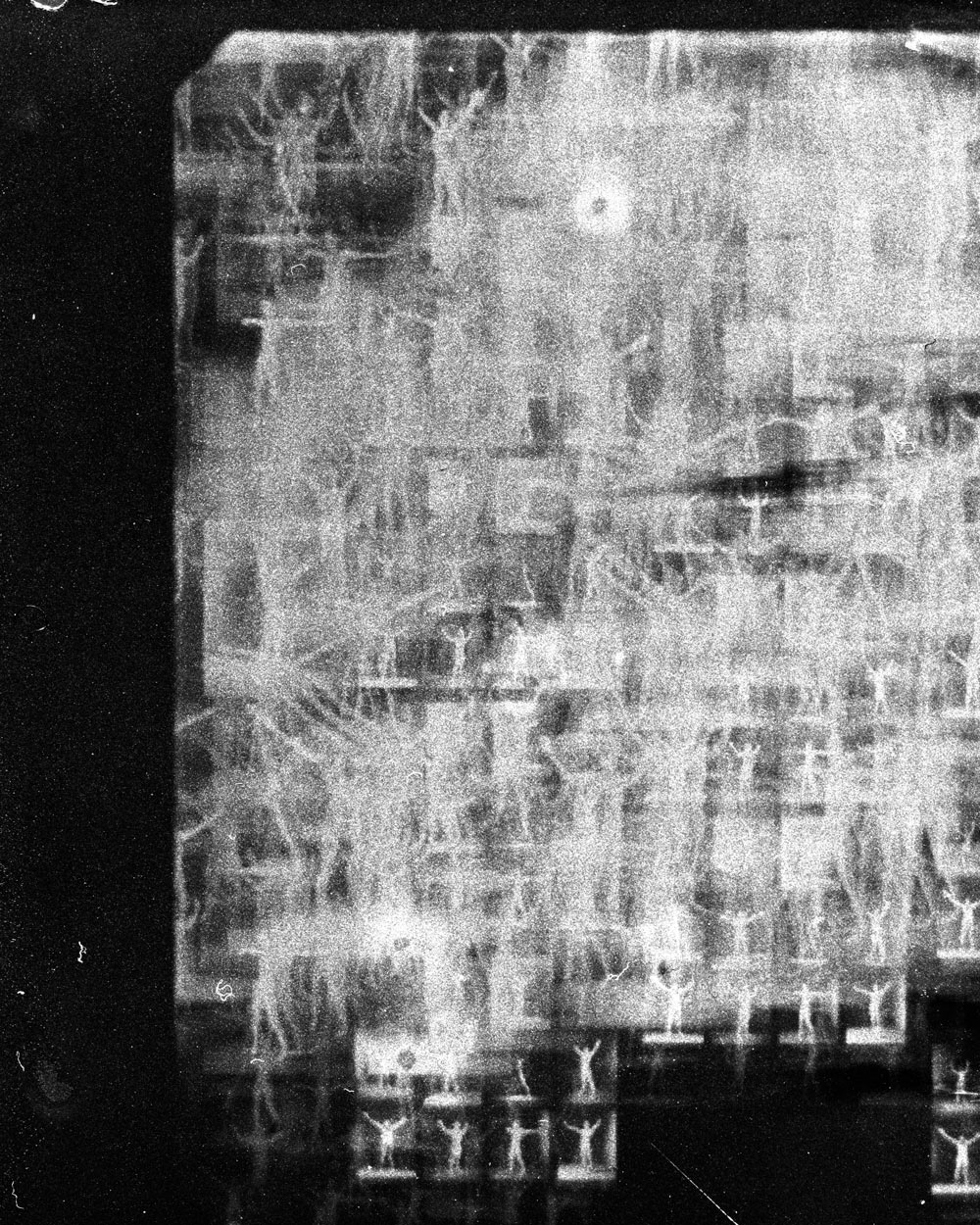

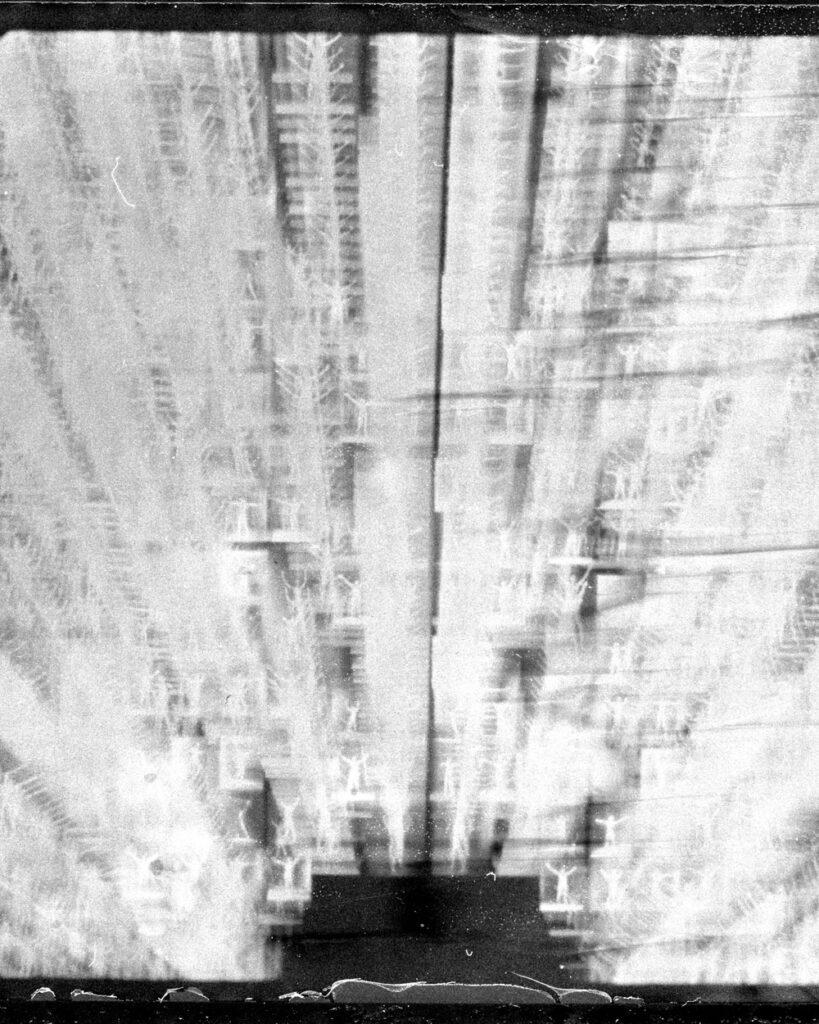

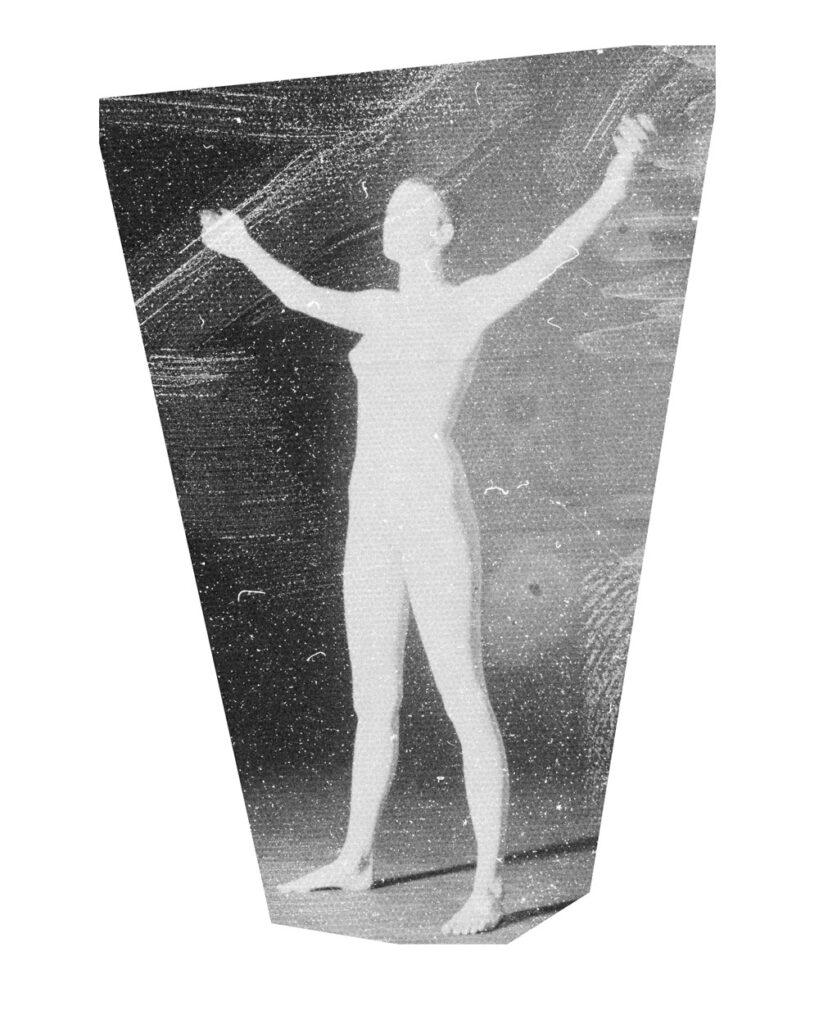

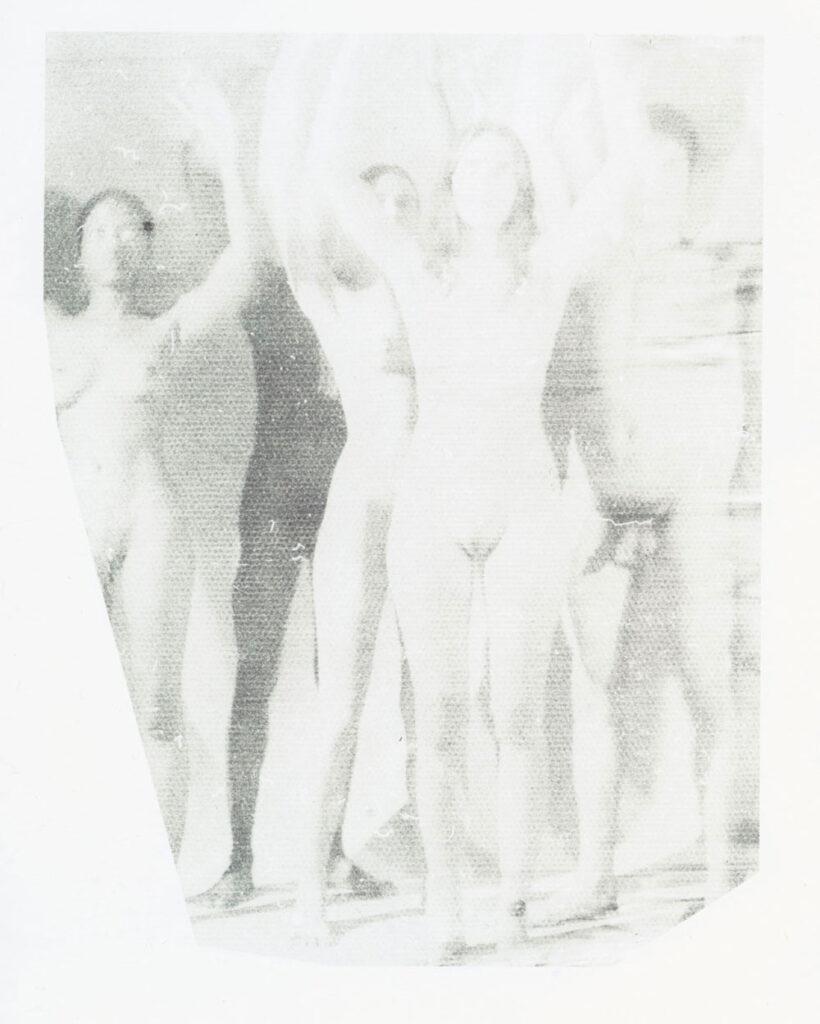

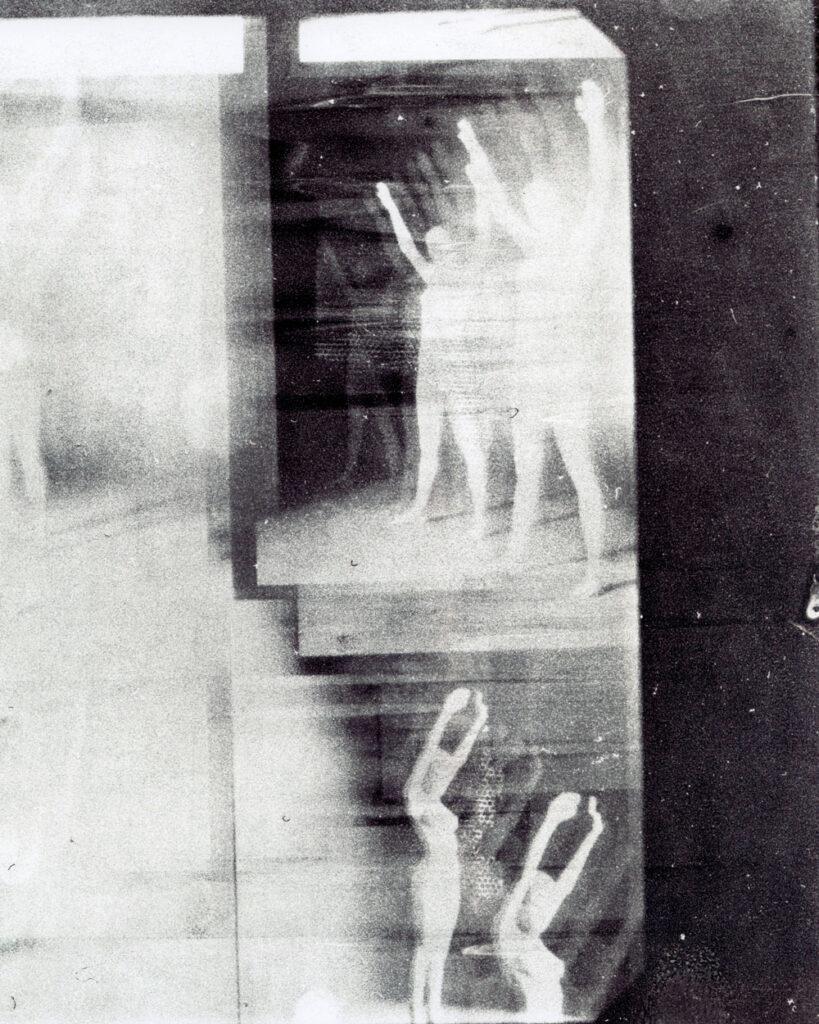

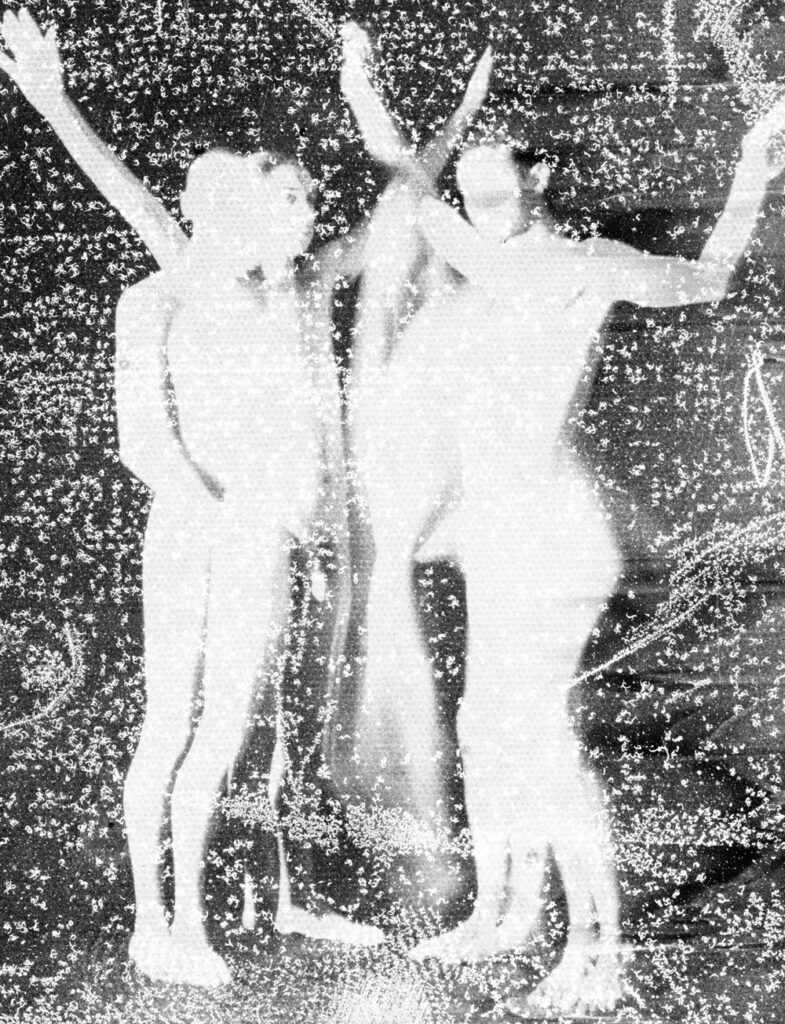

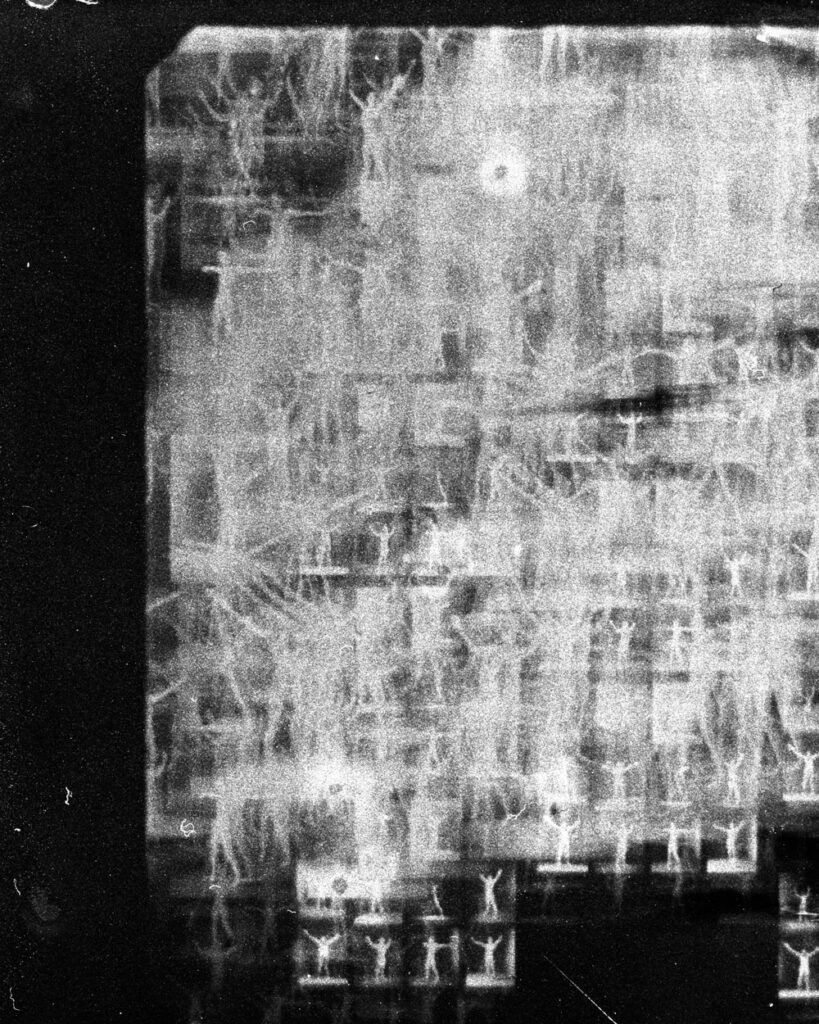

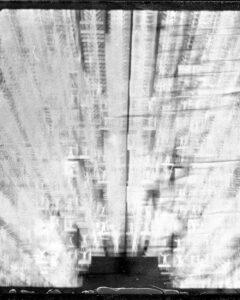

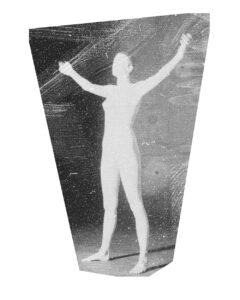

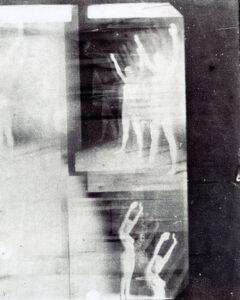

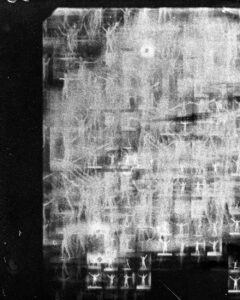

McConnell’s experiments in monochrome are equally beguiling as visual counterpoint. His portrait series of Ibizan clubbers, long in the season, was reworked for his book Sex, Drugs & Magick (Book II), published in 2014. For this project, McConnell photocopied the original chromogenic prints.

The subsequent portraits have a contrast density and a sooty patination that hum with obfuscation, so, at one remove, you see the devotion to the cause all the more clearly; haggardness is etched across taut skin and lowered eyelids.

All of McConnell’s photographs articulate the isolation of the individual in the midst of mass communion. They persistently ask, What happens to the self in the collective will to enter the utopian space of the fantastic? McConnell describes it as “the delirious but bittersweet pleasure of losing oneself to hedonism from the view of someone who saw it from within.” These images suggest that the utopian urge is illusory, a phantasmagoria that flashes past the eyes as the hit reaches the brain.

For McConnell, photographs are not intended as historical records but as a way into memory. They enshrine the belief that only by resurrecting our individual or collective pasts can we address a transformed future. With the return of illegal raves in the wake of COVID-19 lockdowns, we are once again reminded of the importance of the color of our memories.

Alistair O’Neill

Alistair O’Neill is a professor of fashion history and theory at Central Saint Martins, London.