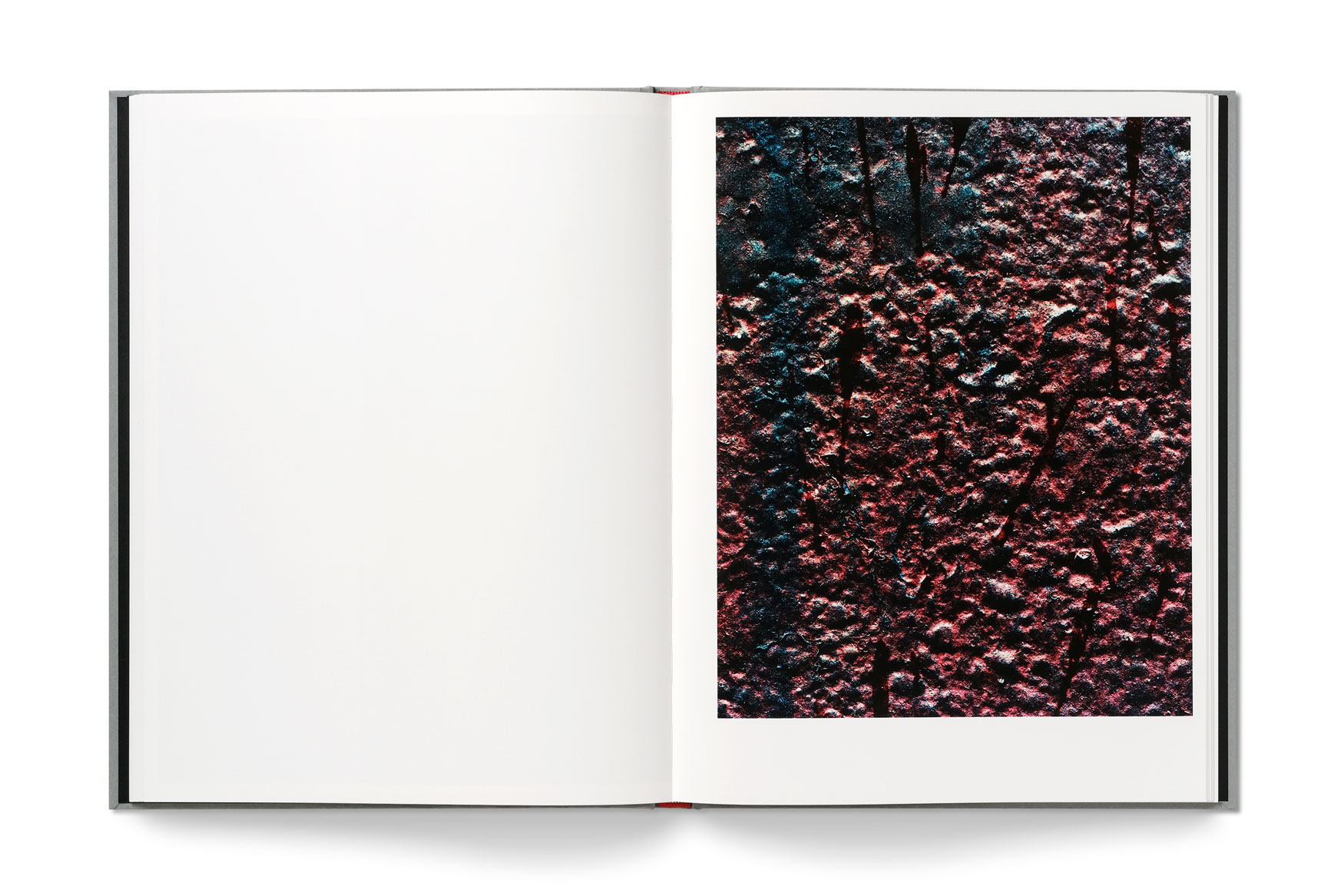

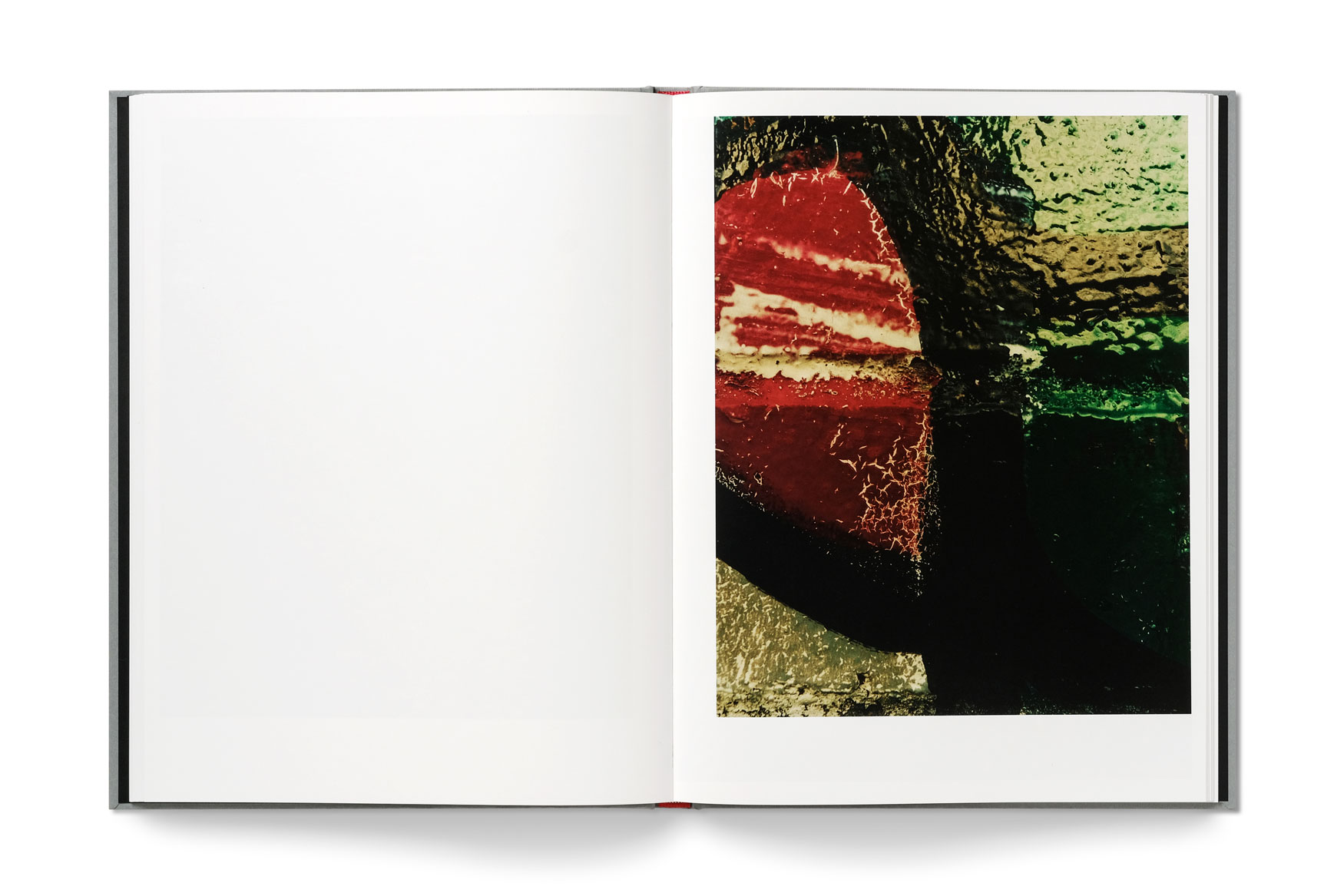

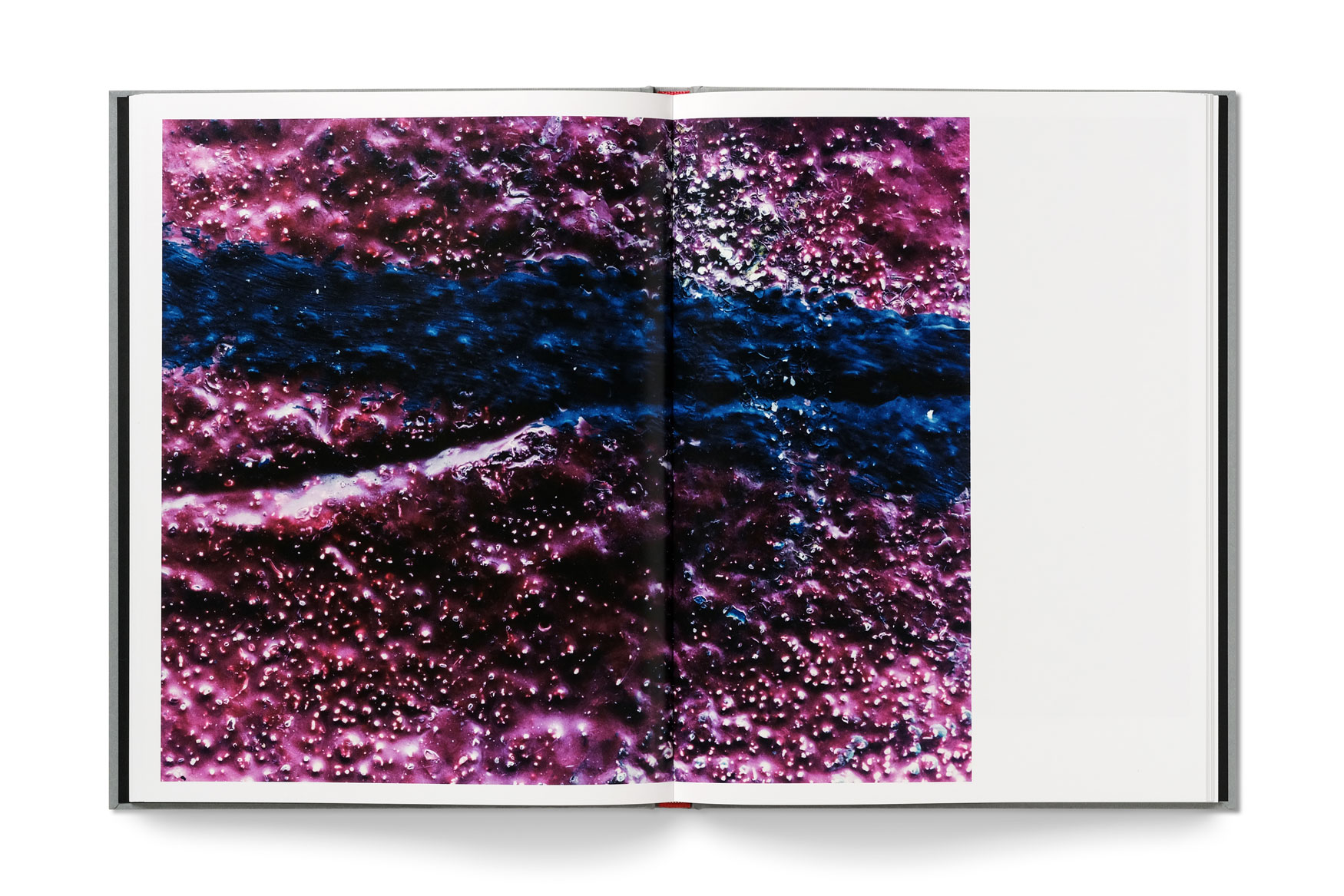

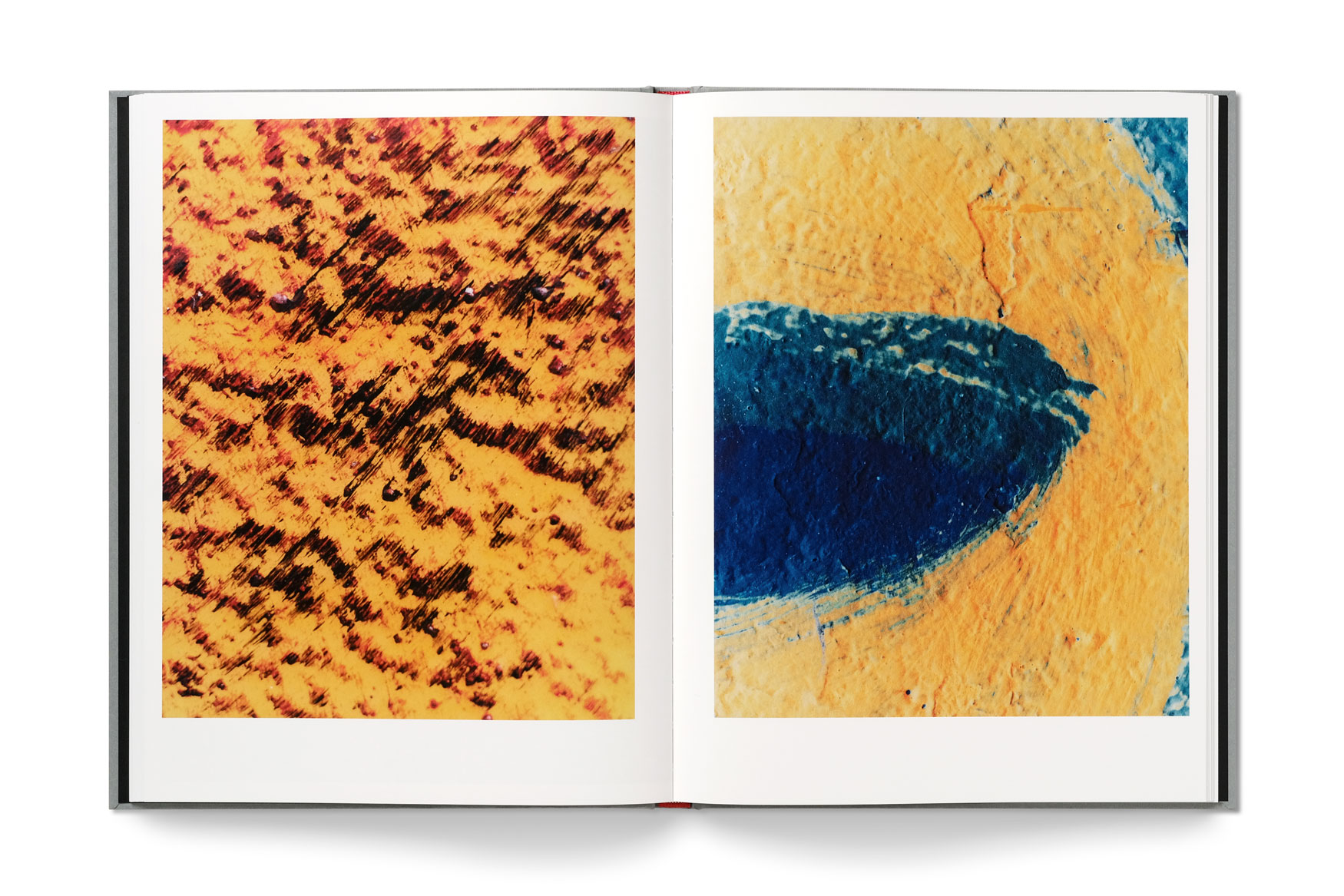

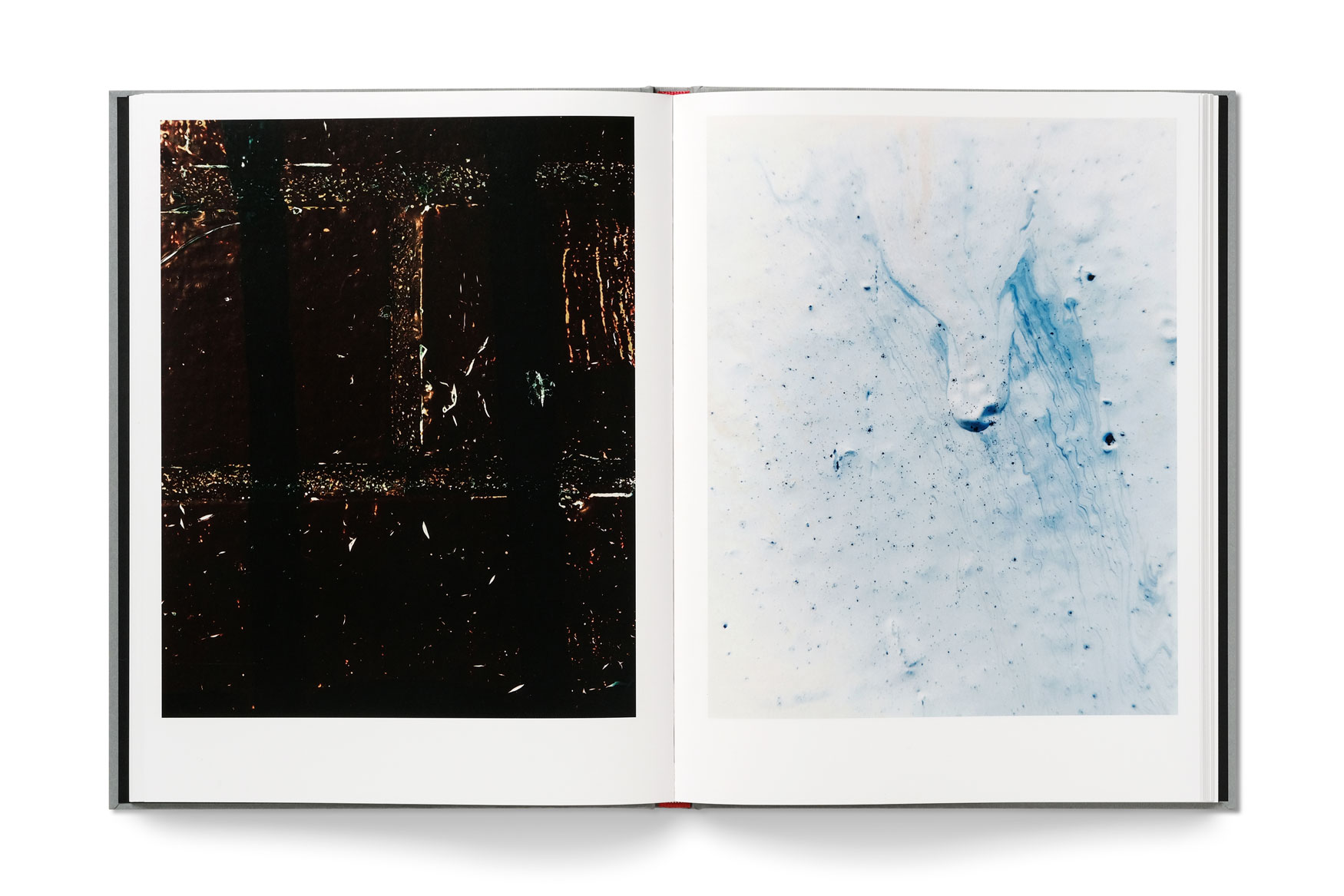

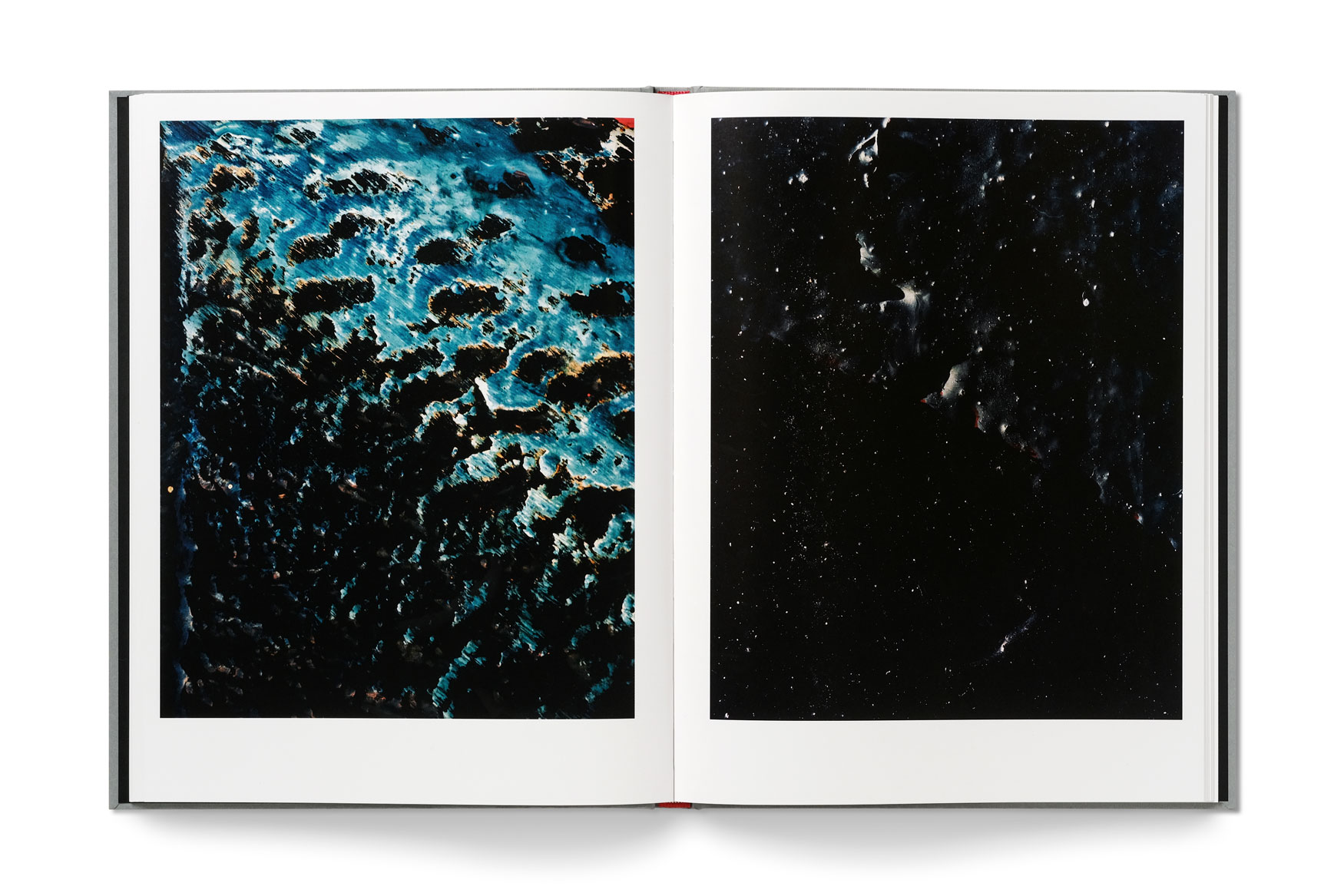

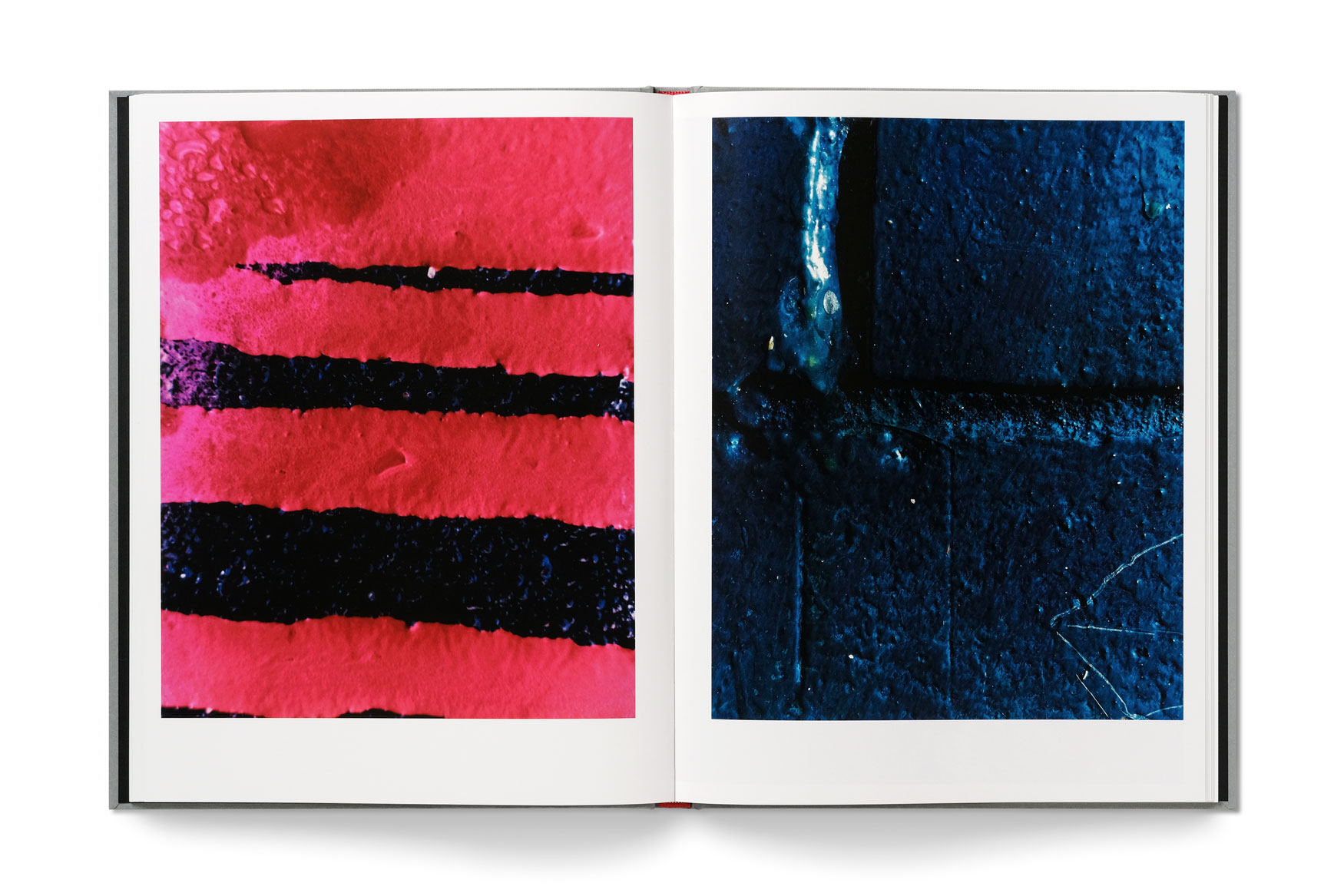

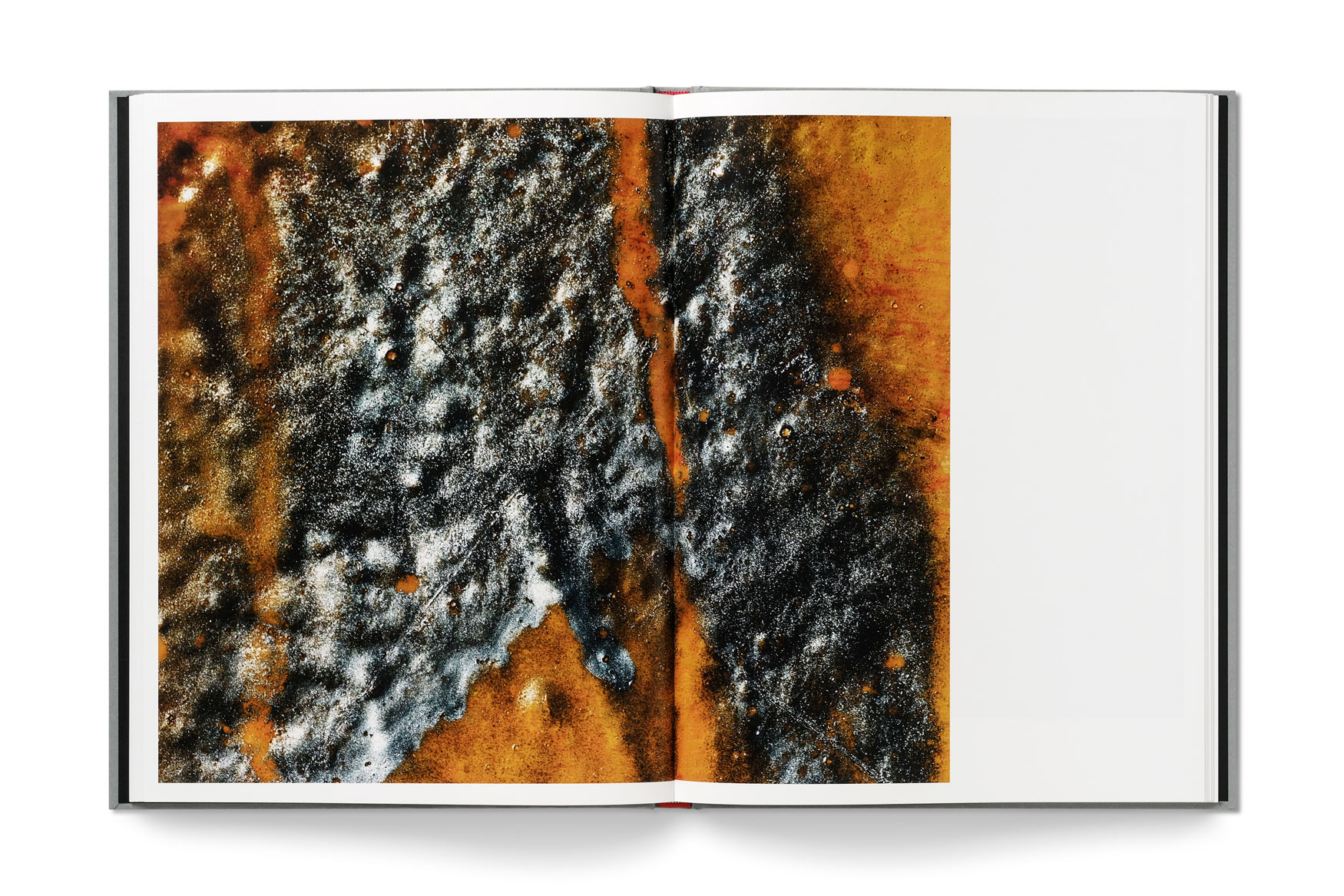

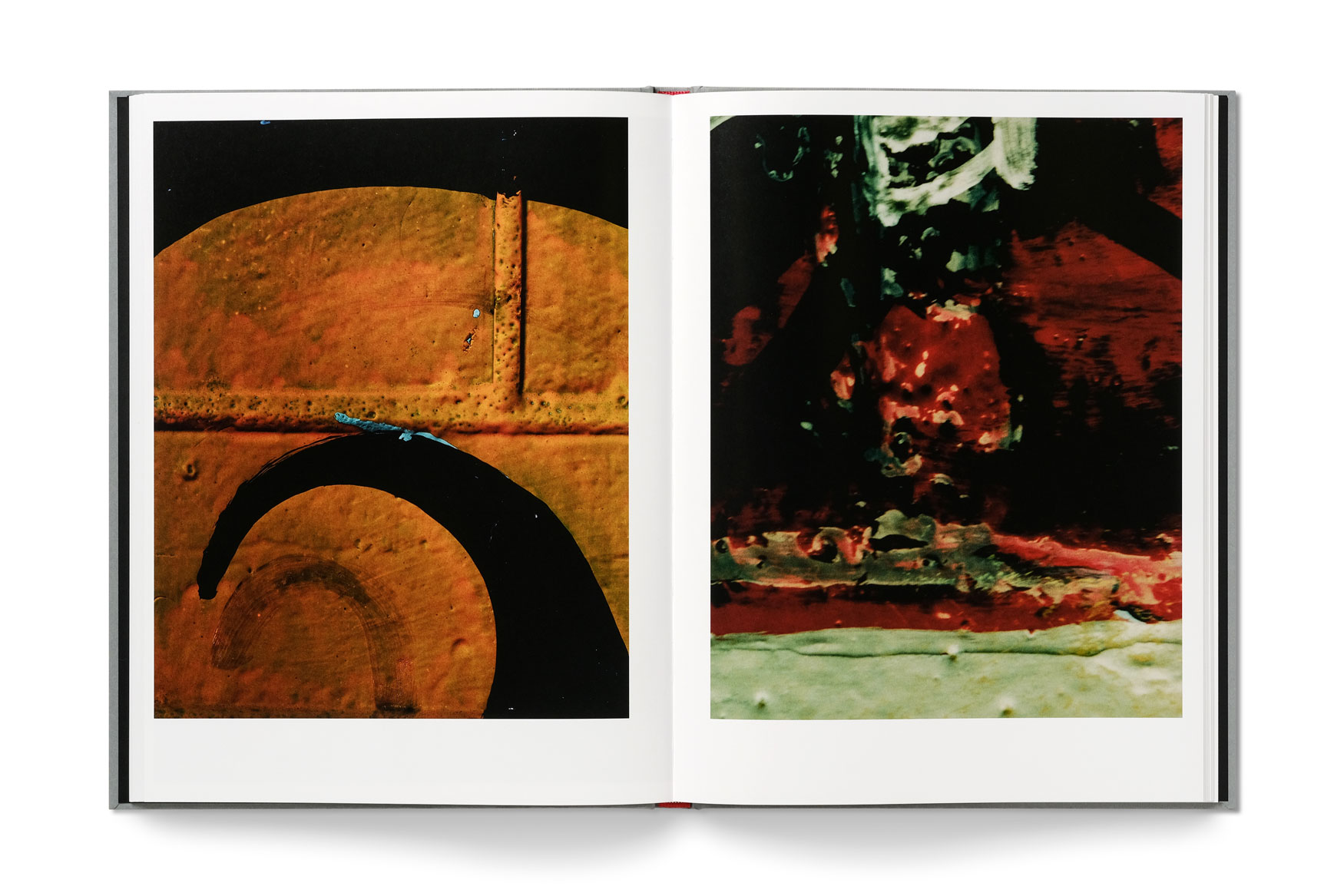

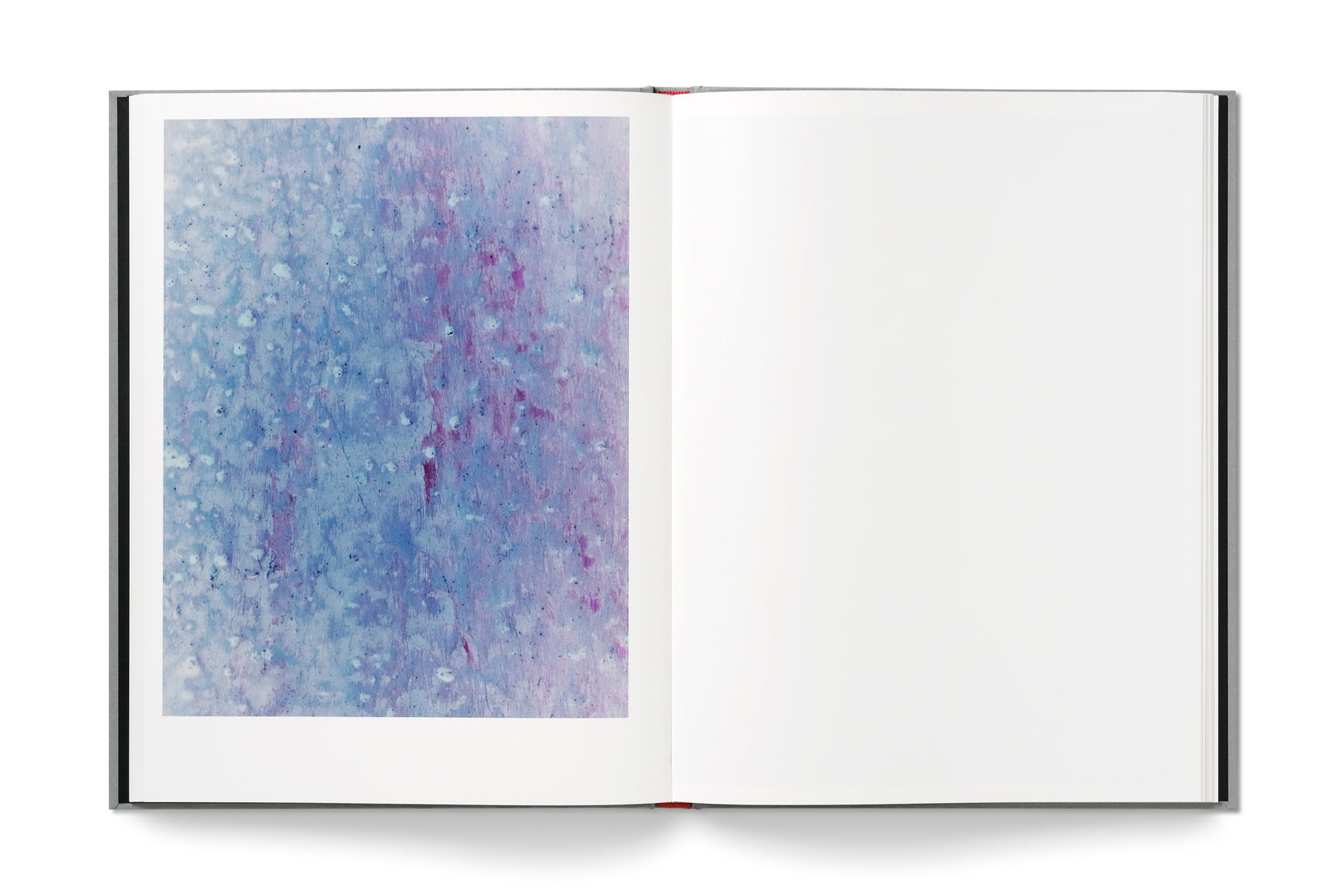

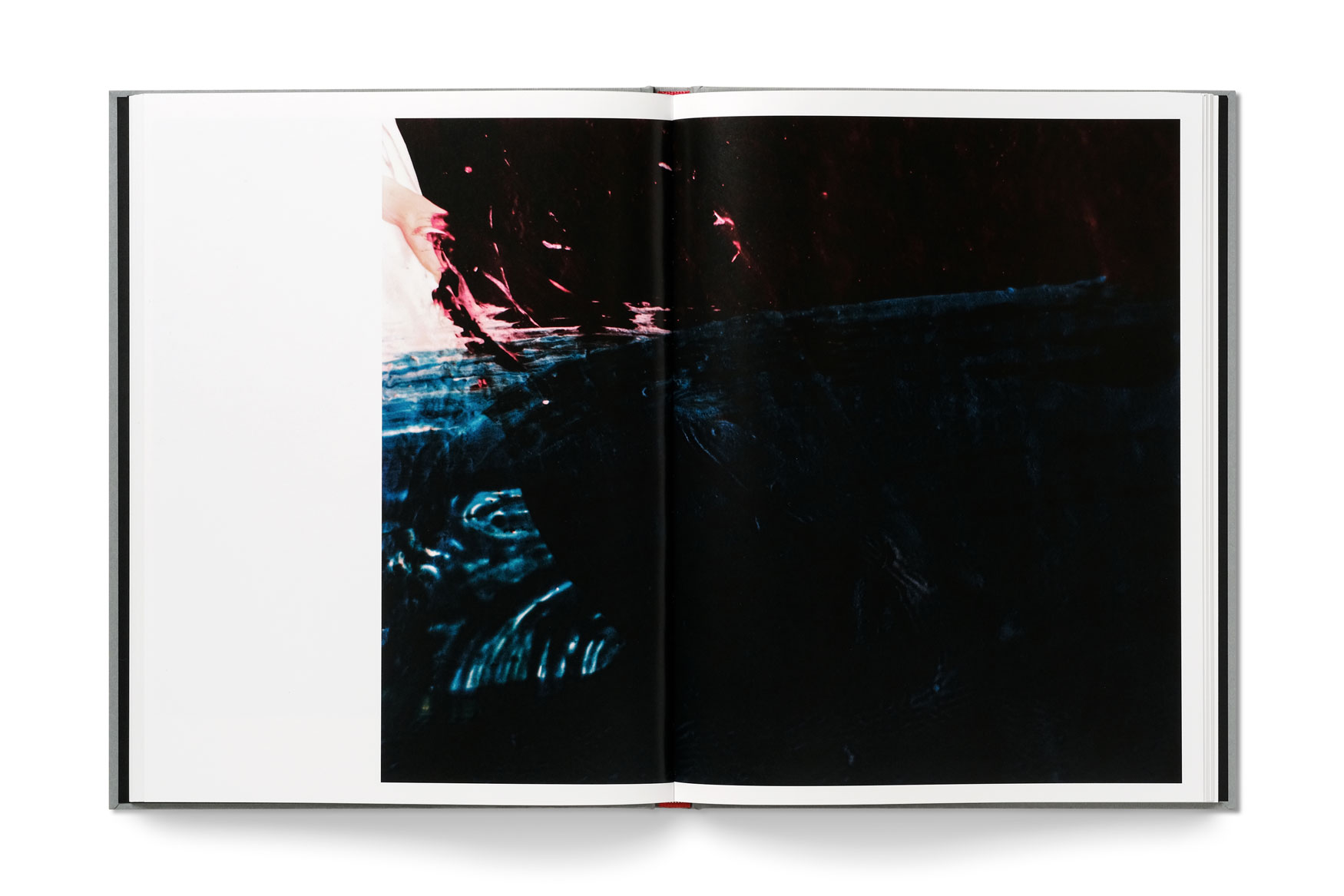

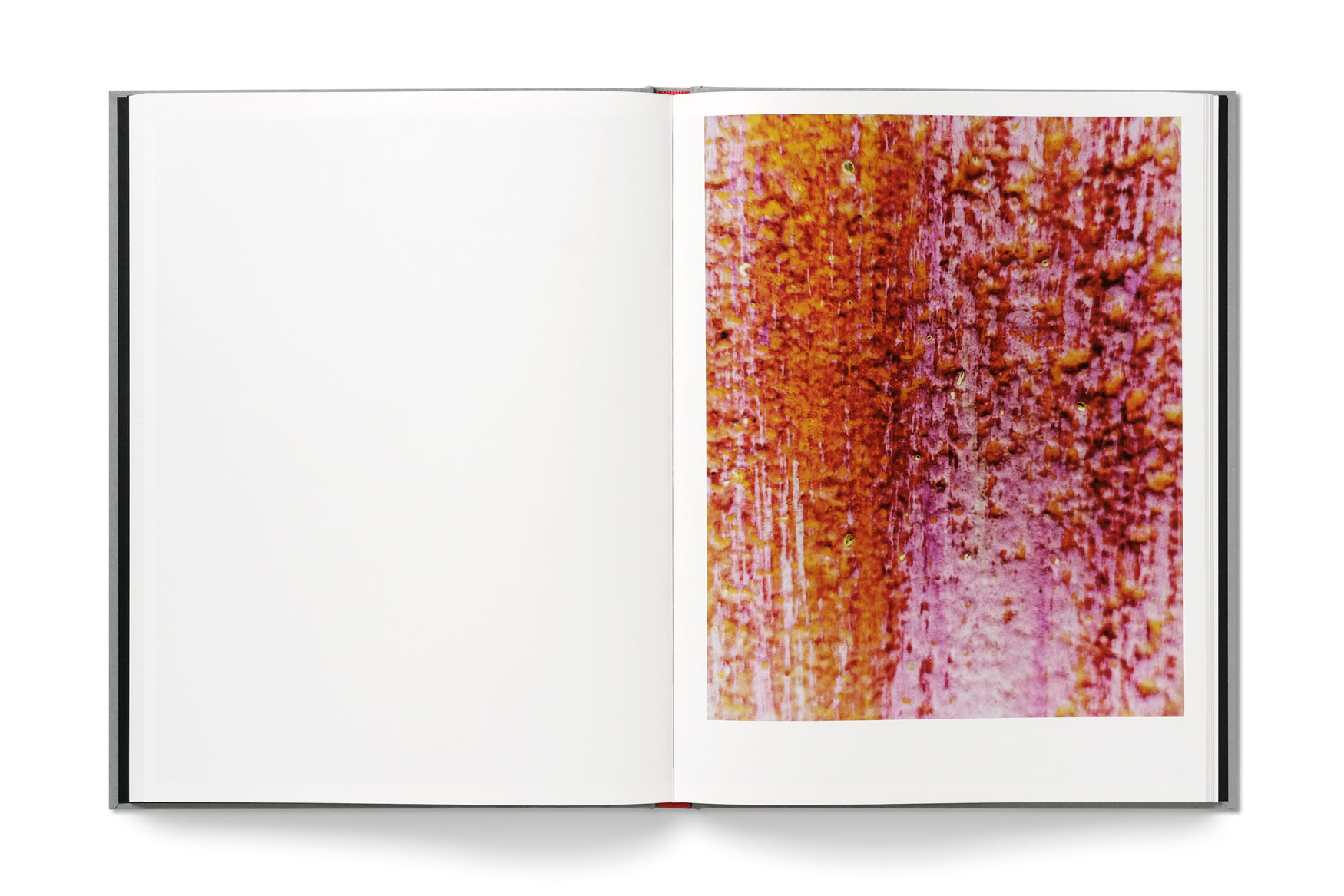

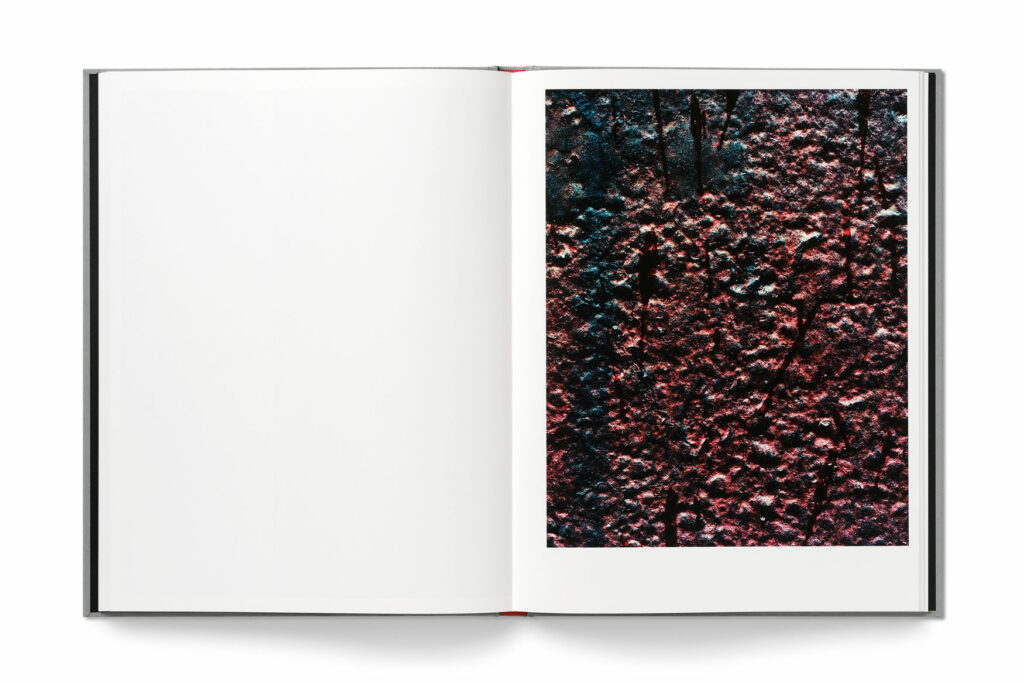

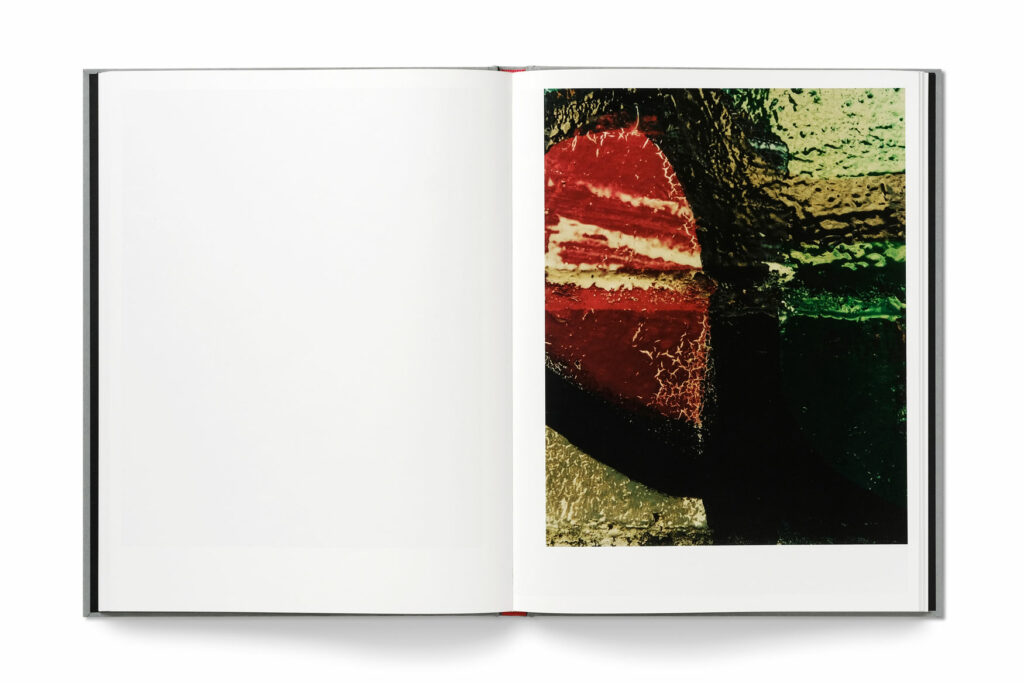

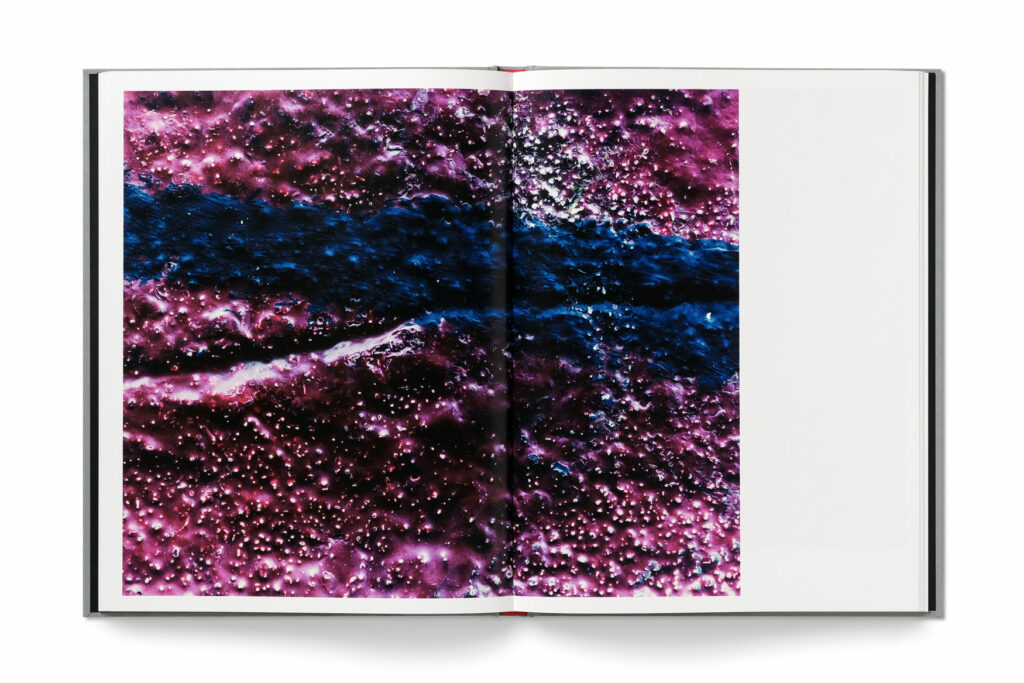

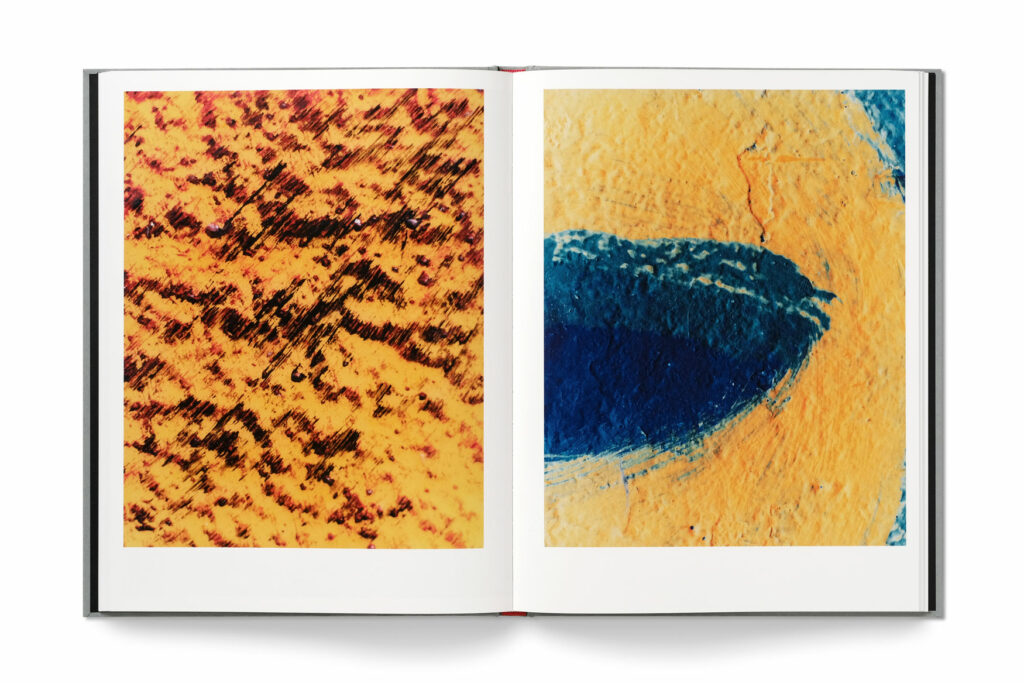

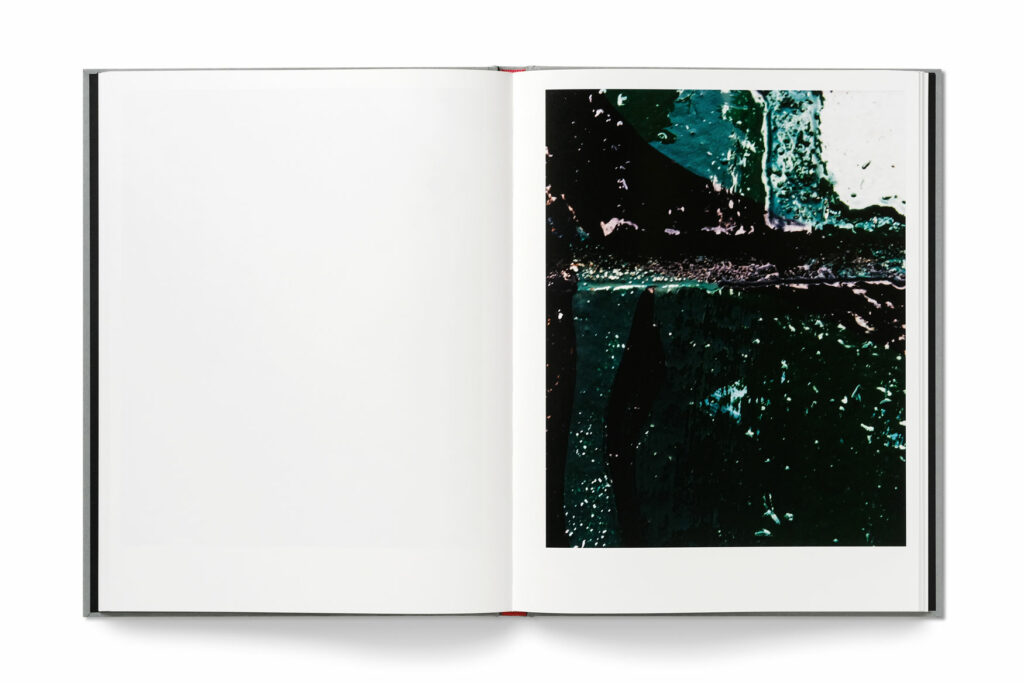

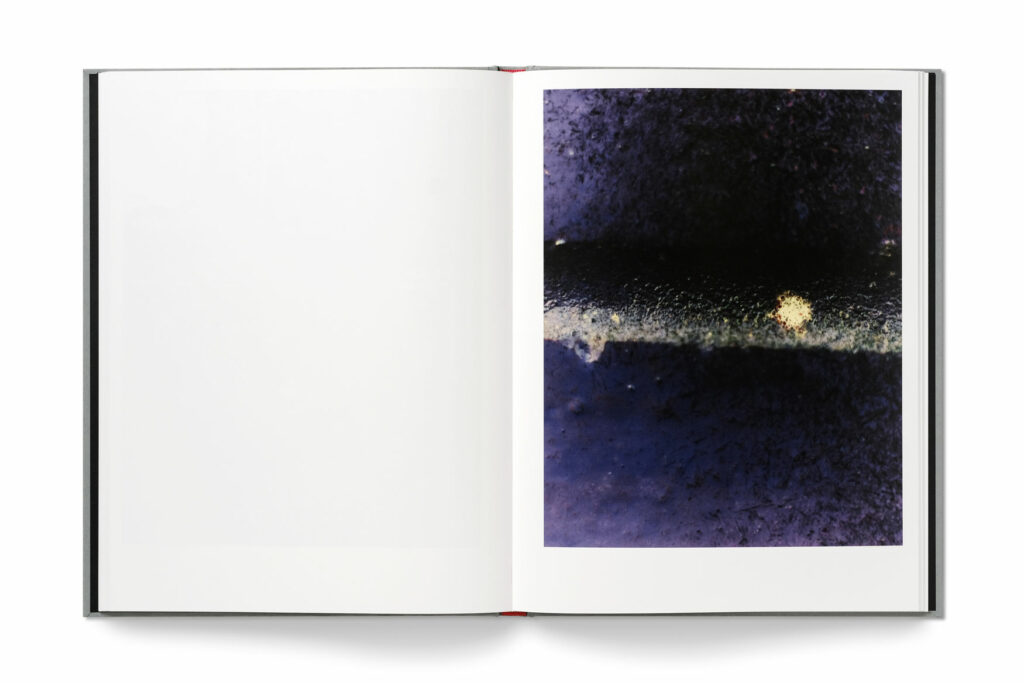

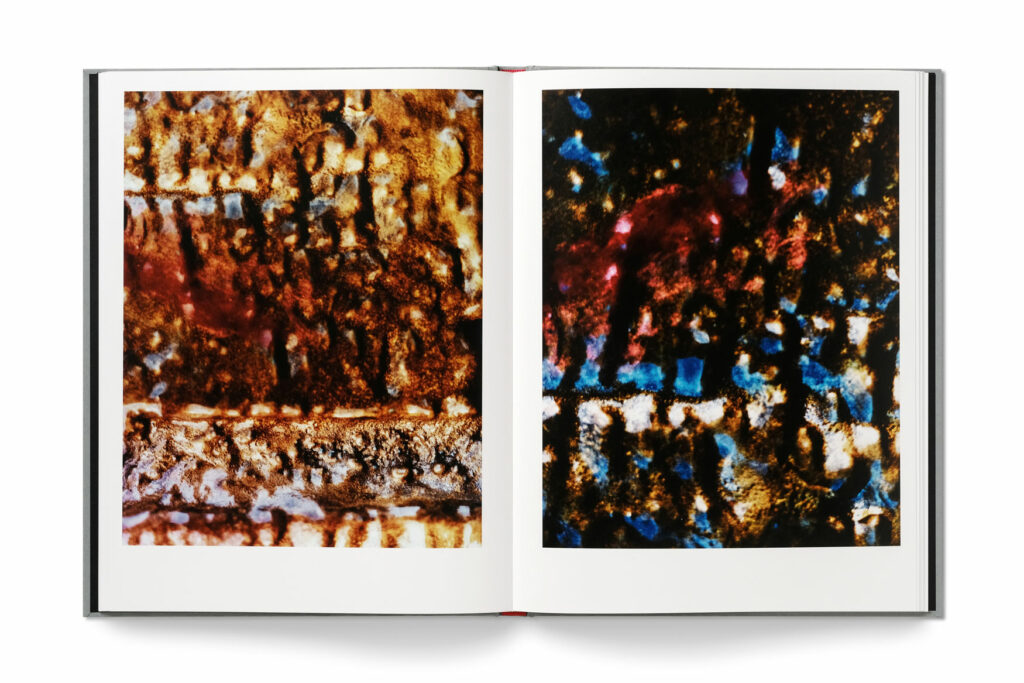

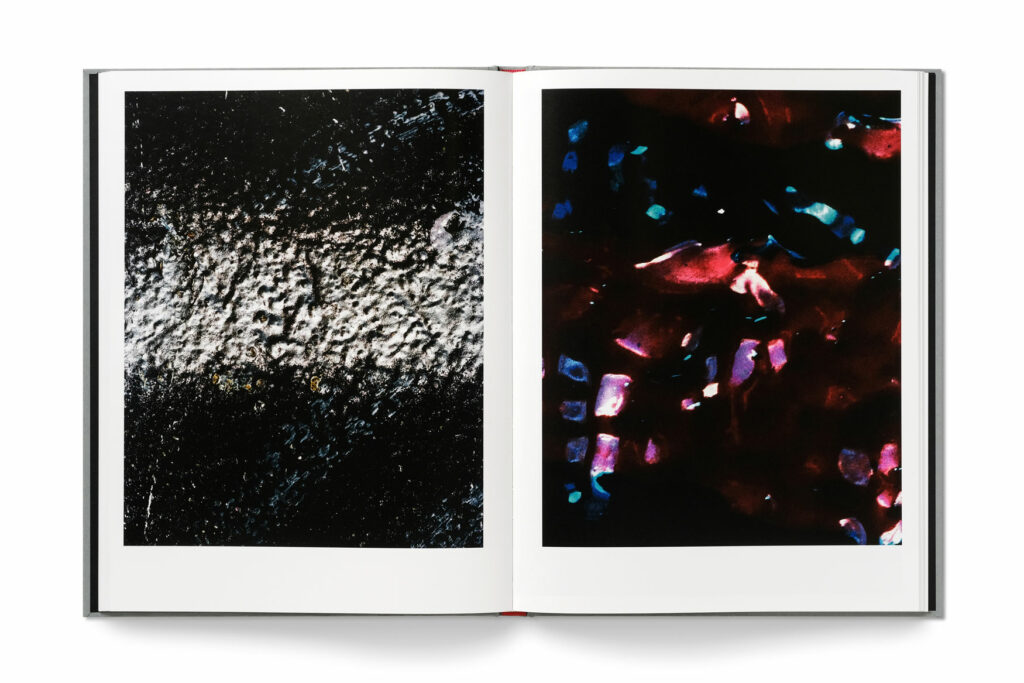

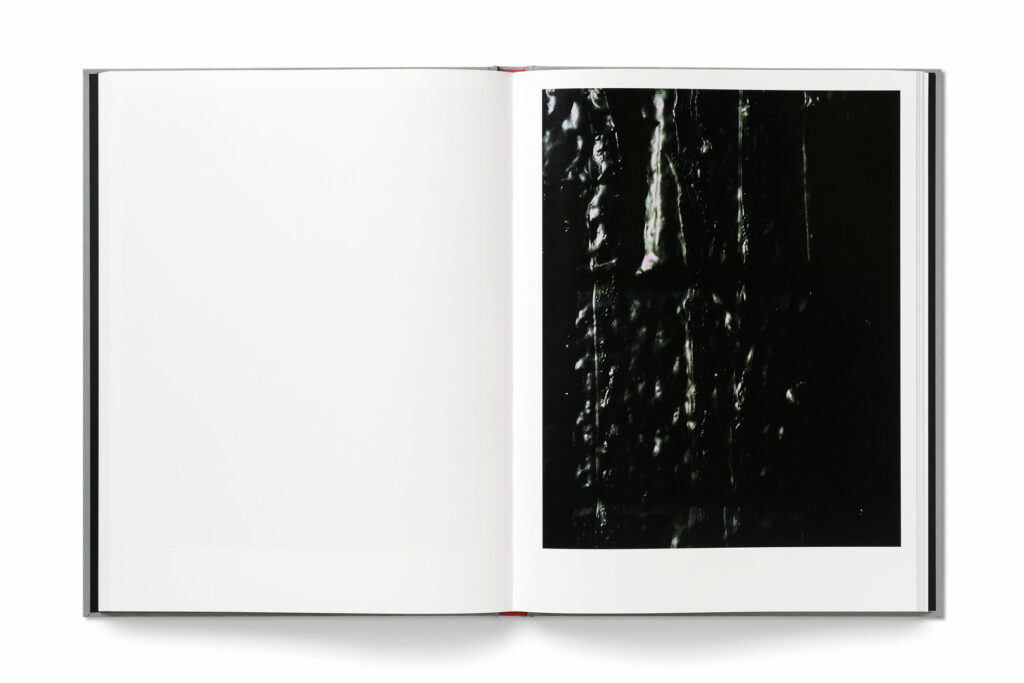

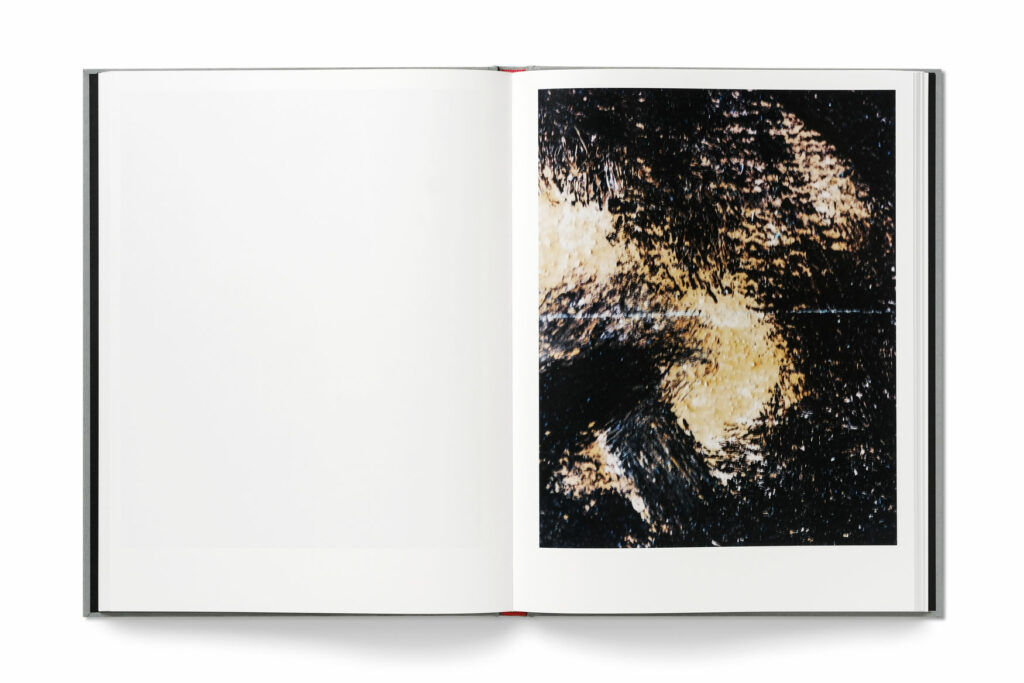

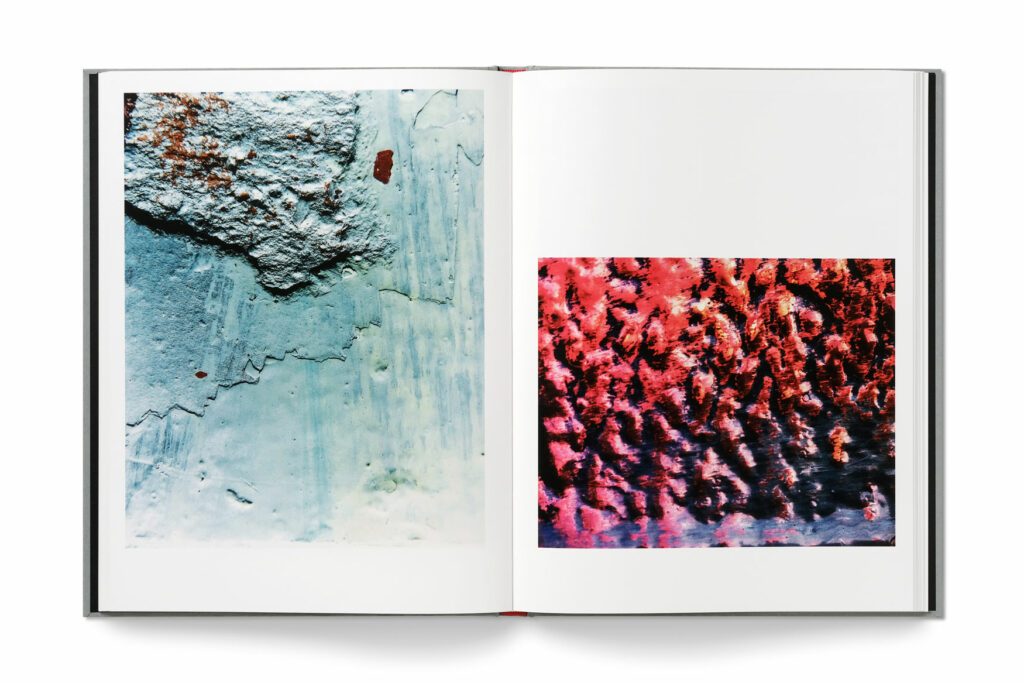

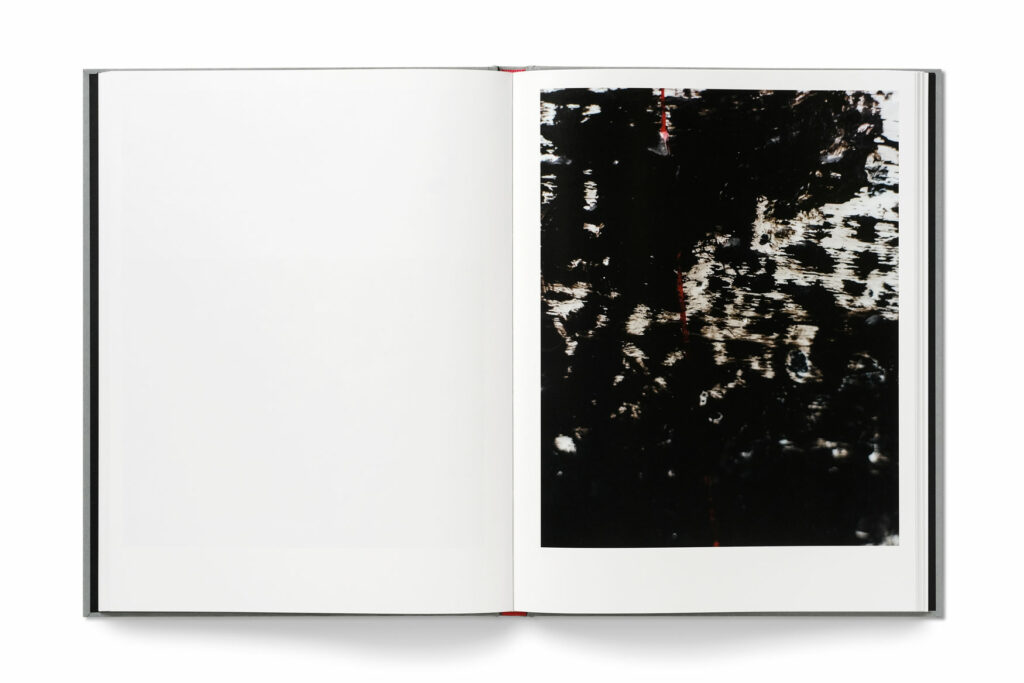

Details of Sectarian Murals:

Abstraction as Survival Strategy and Utopic Appeal

Sarah Allen

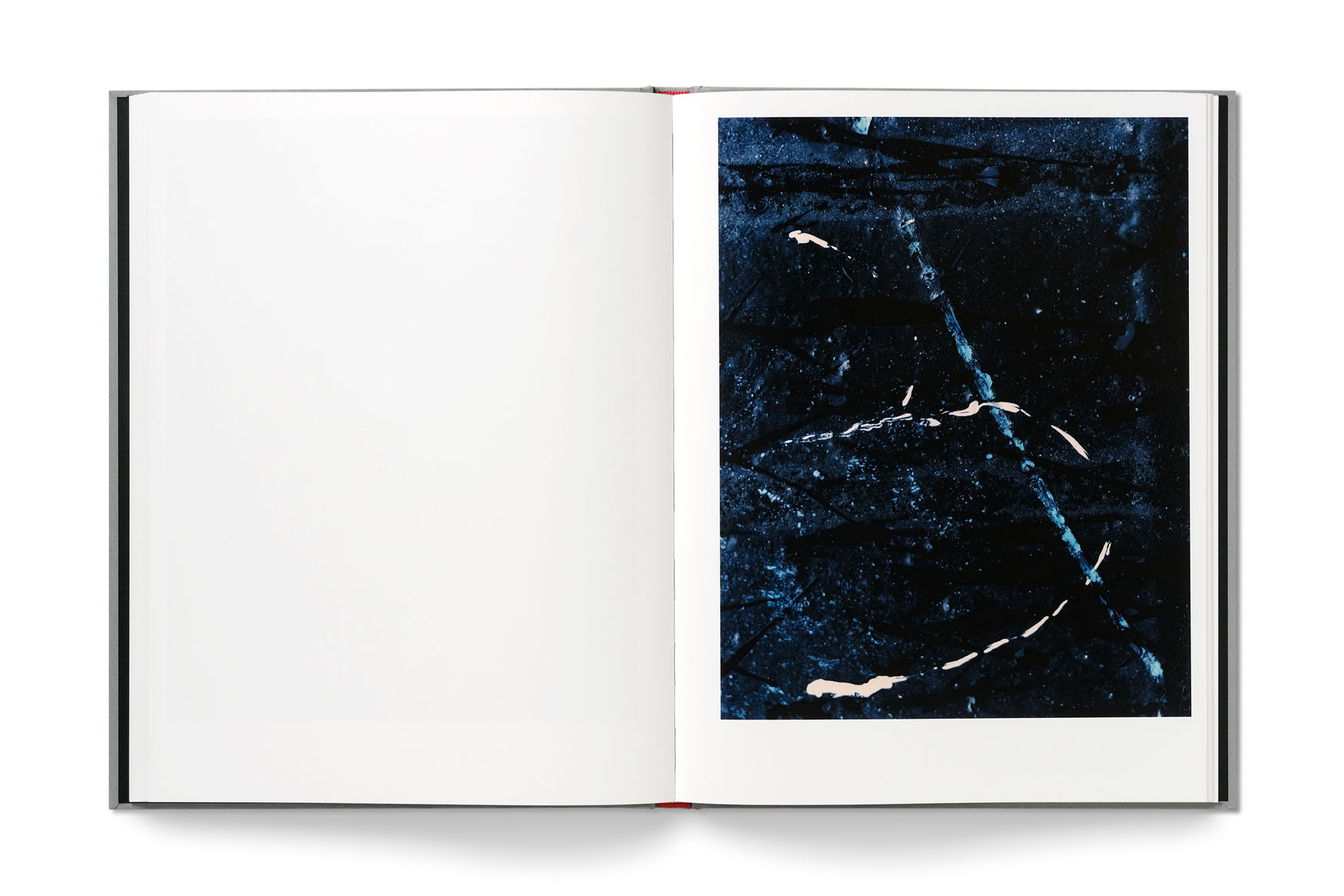

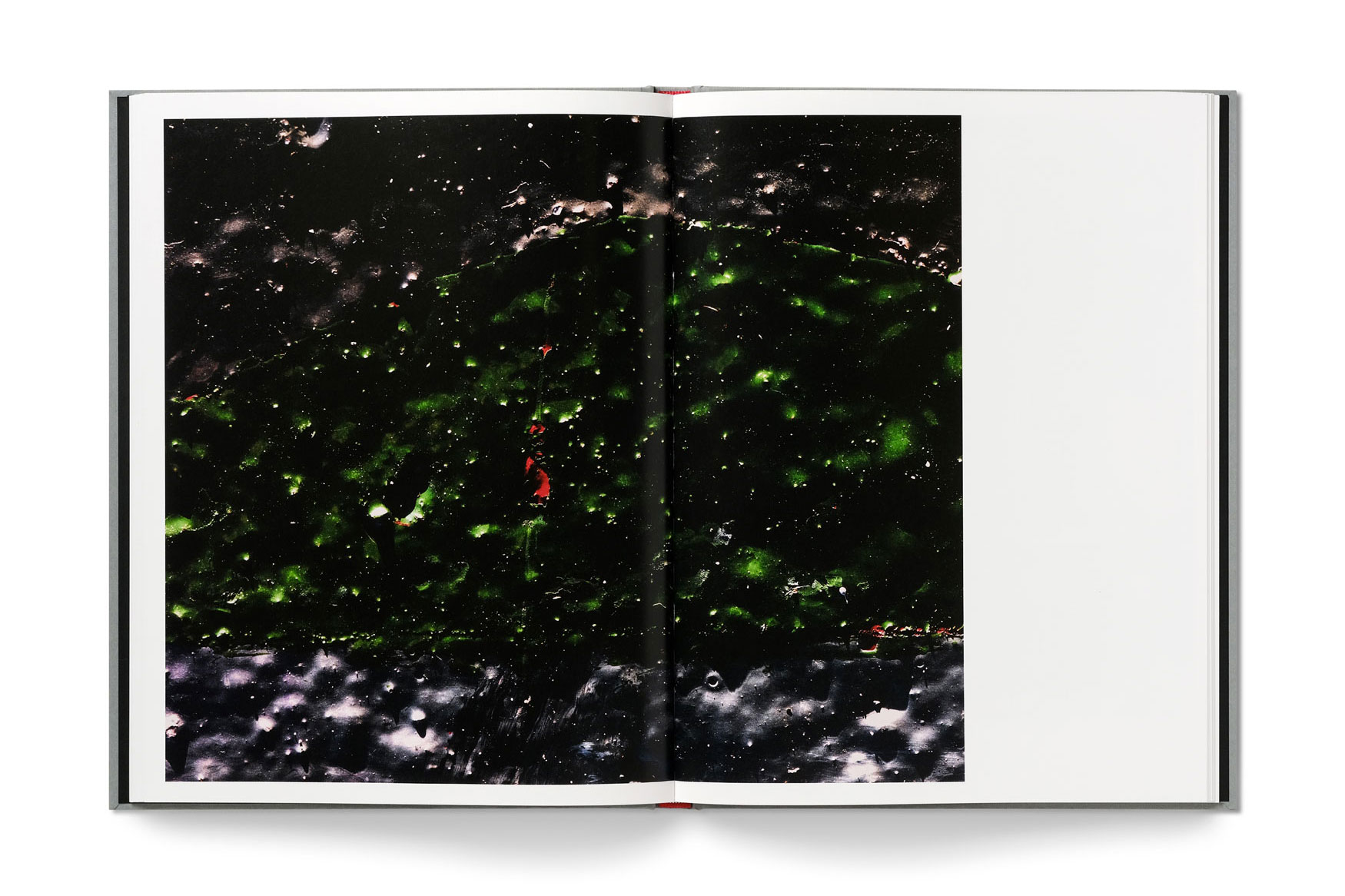

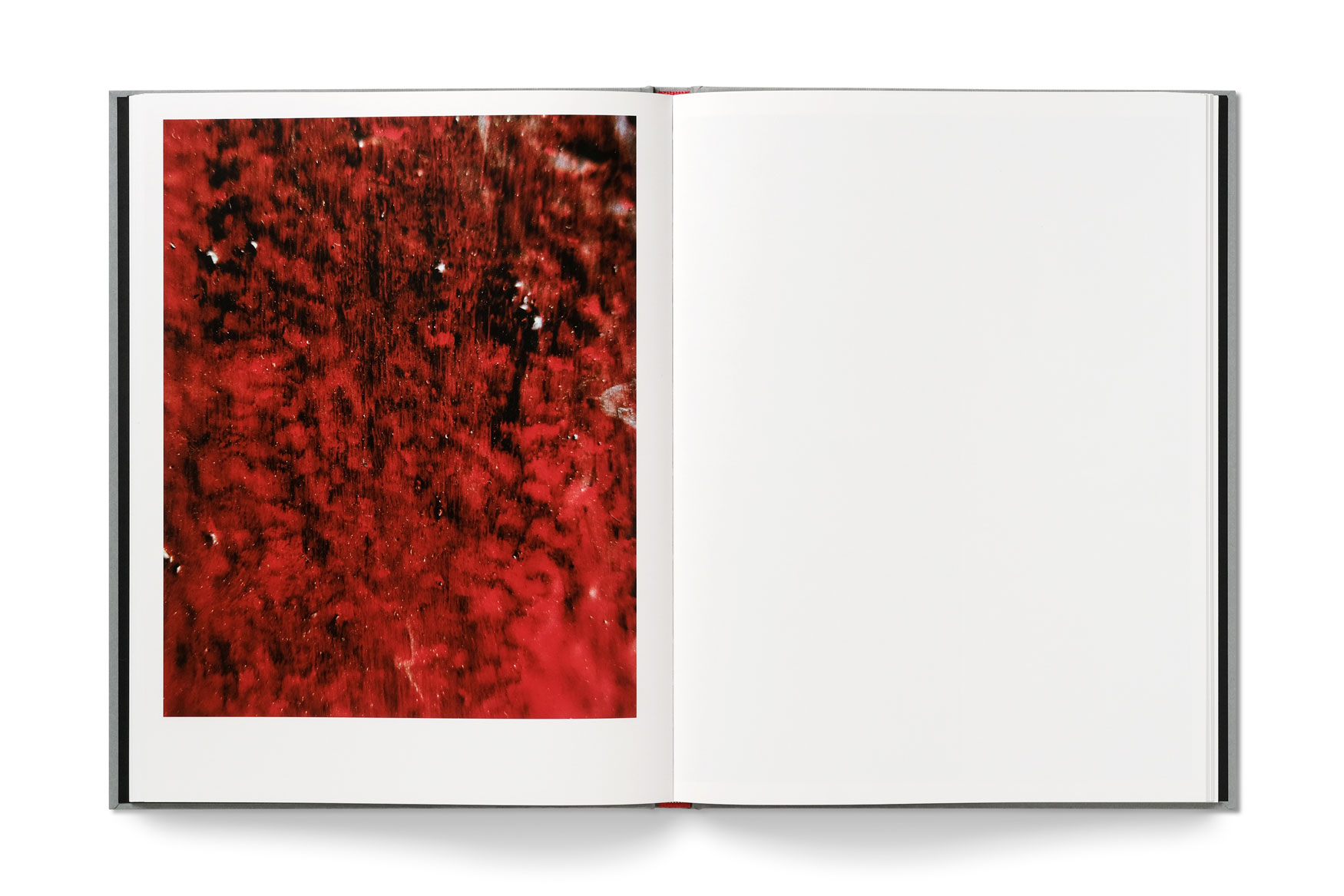

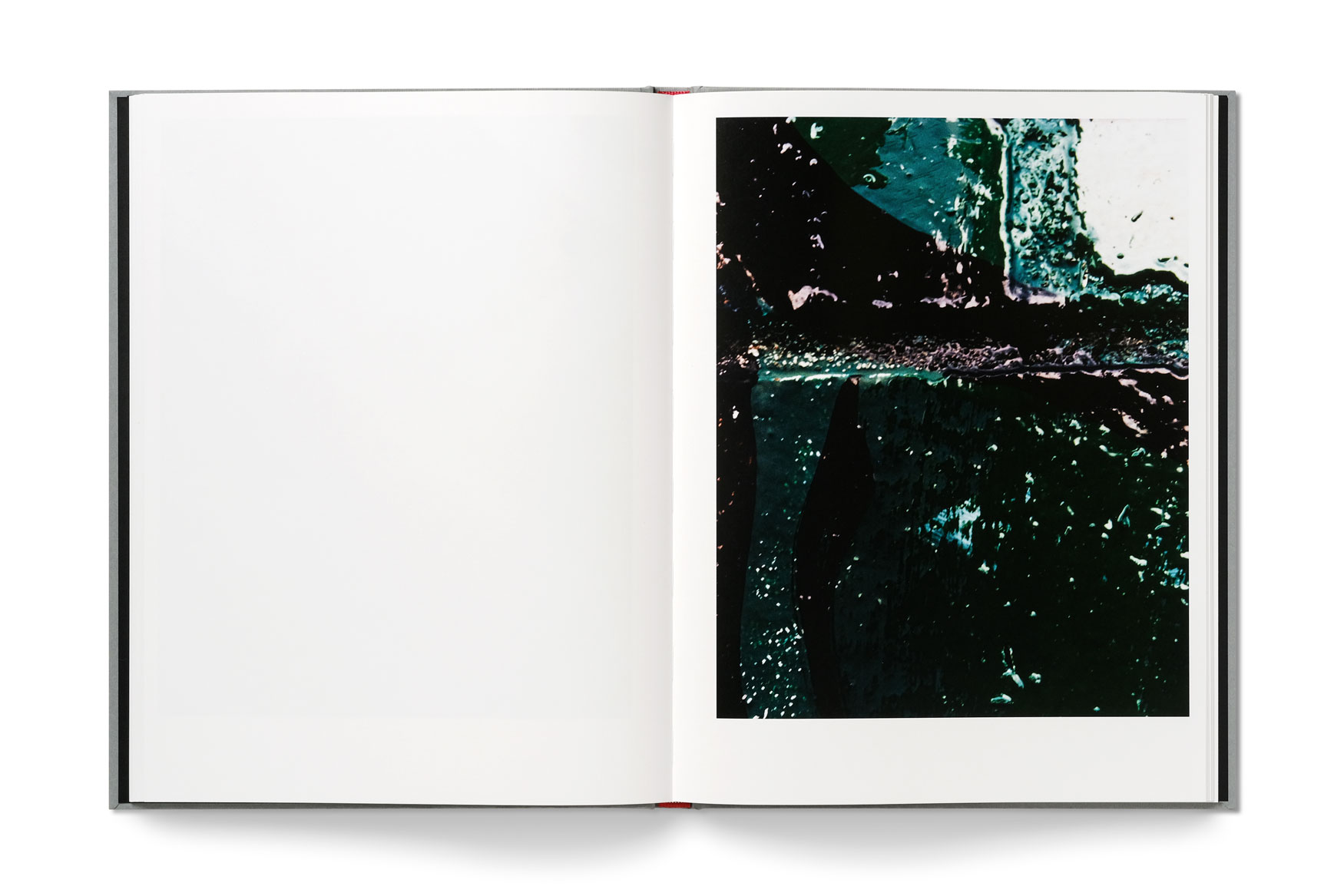

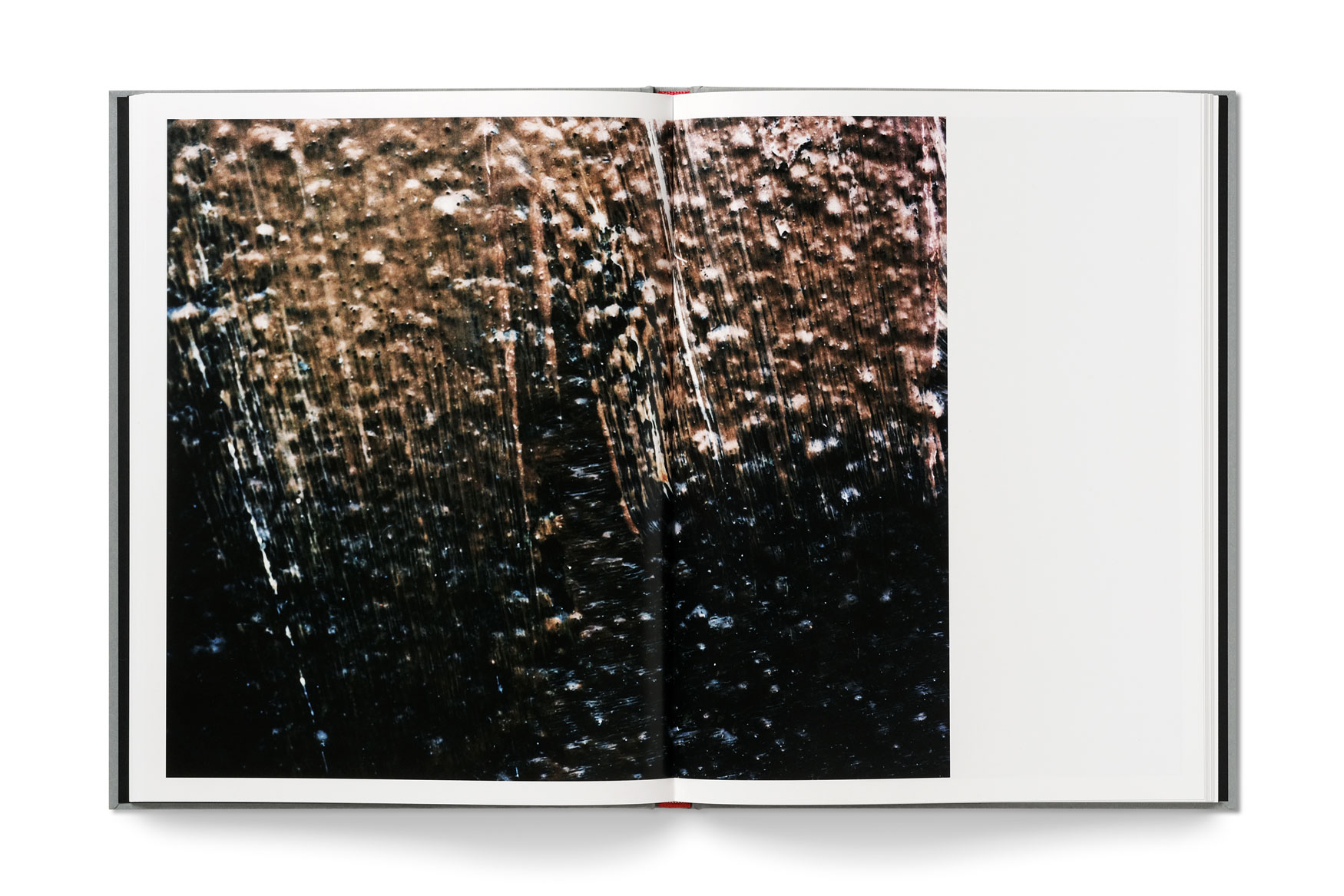

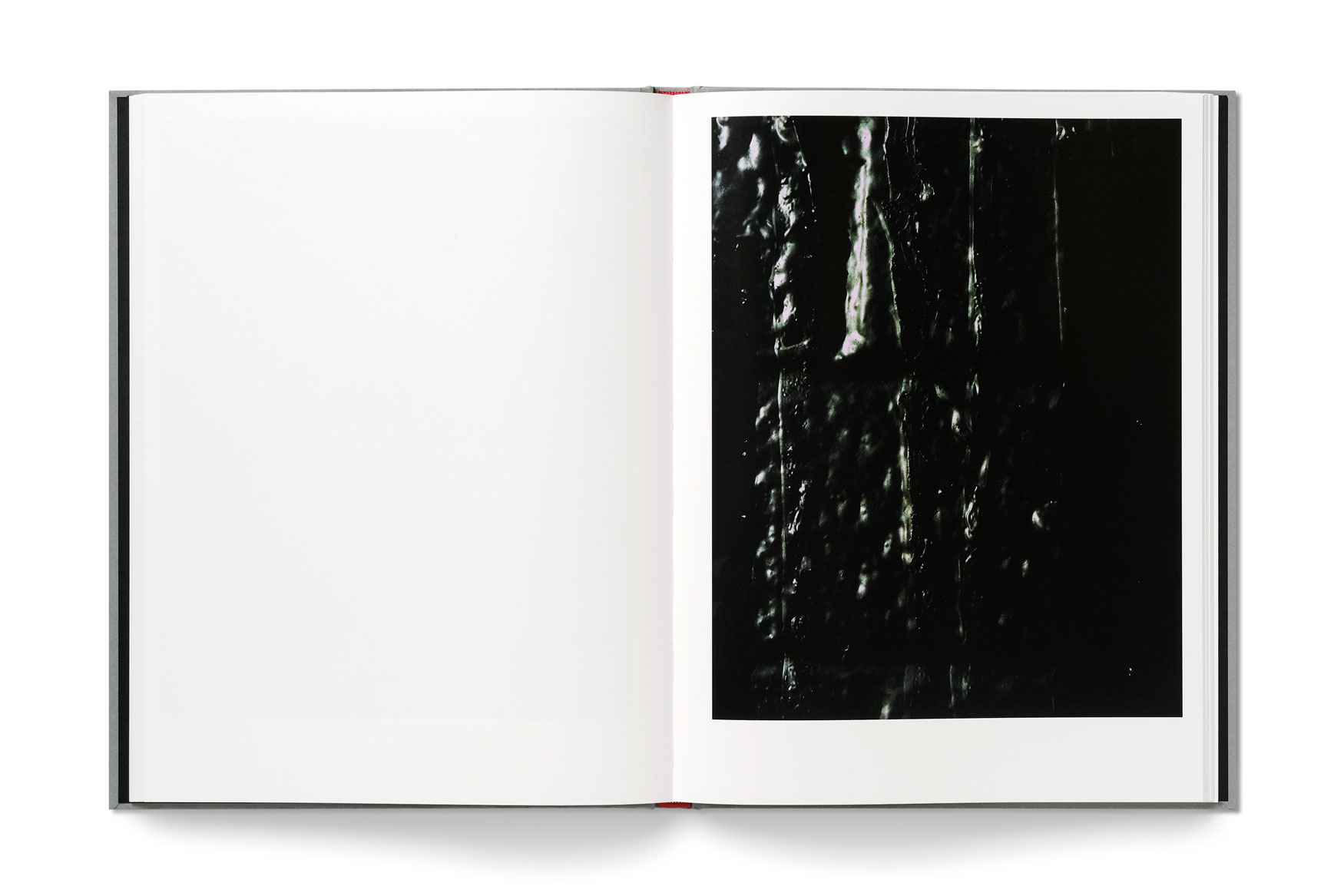

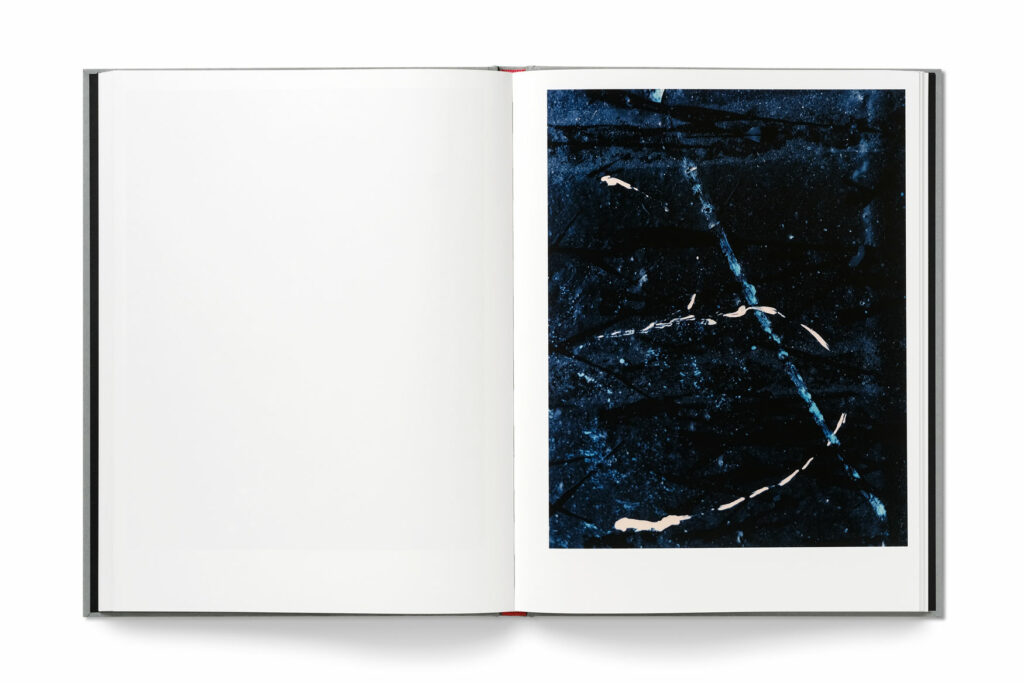

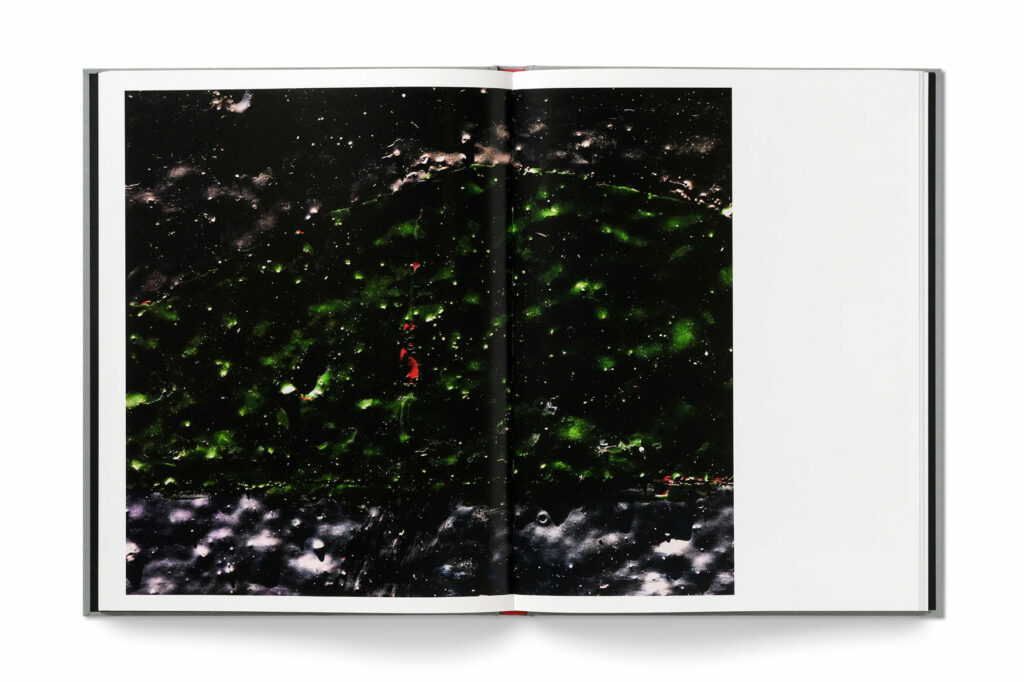

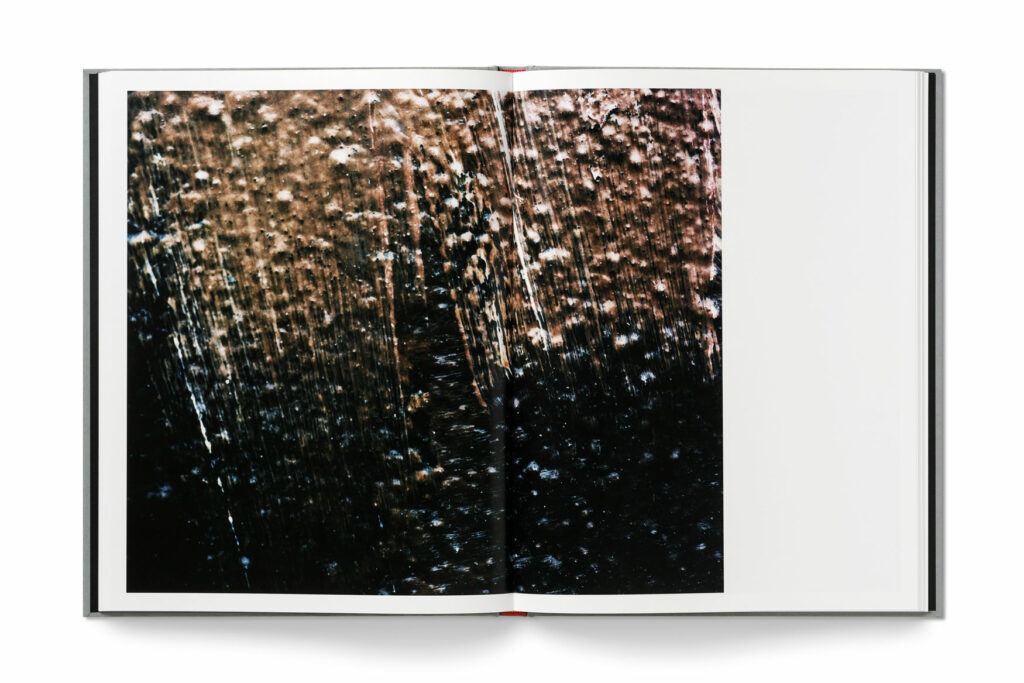

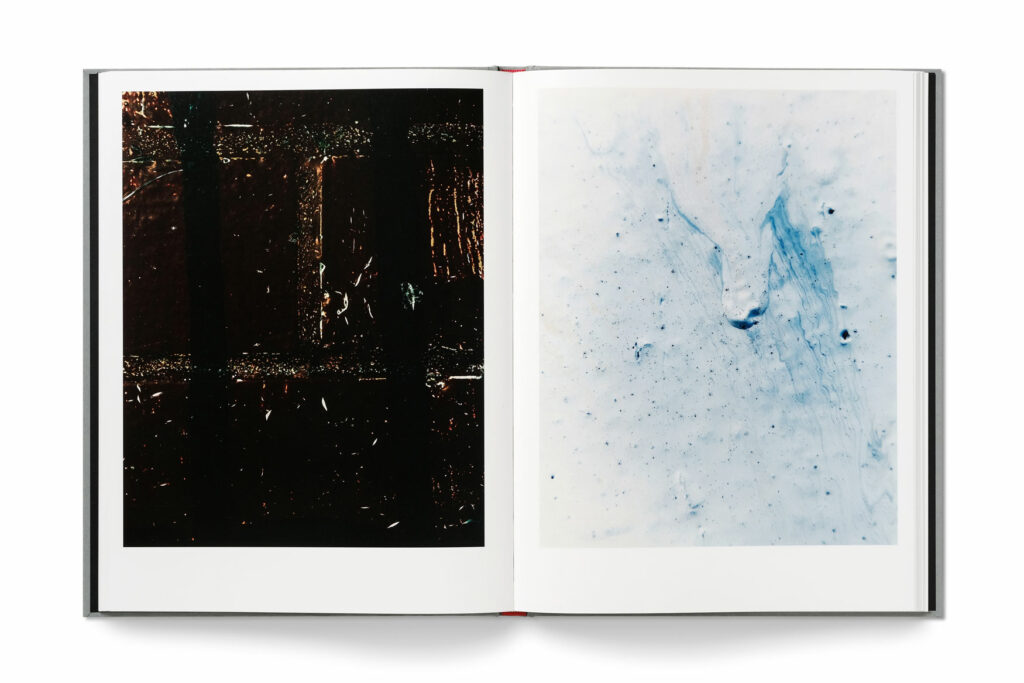

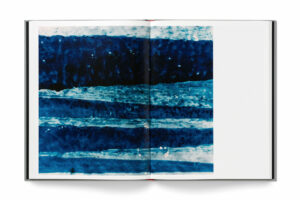

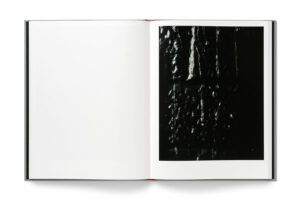

Dark Days

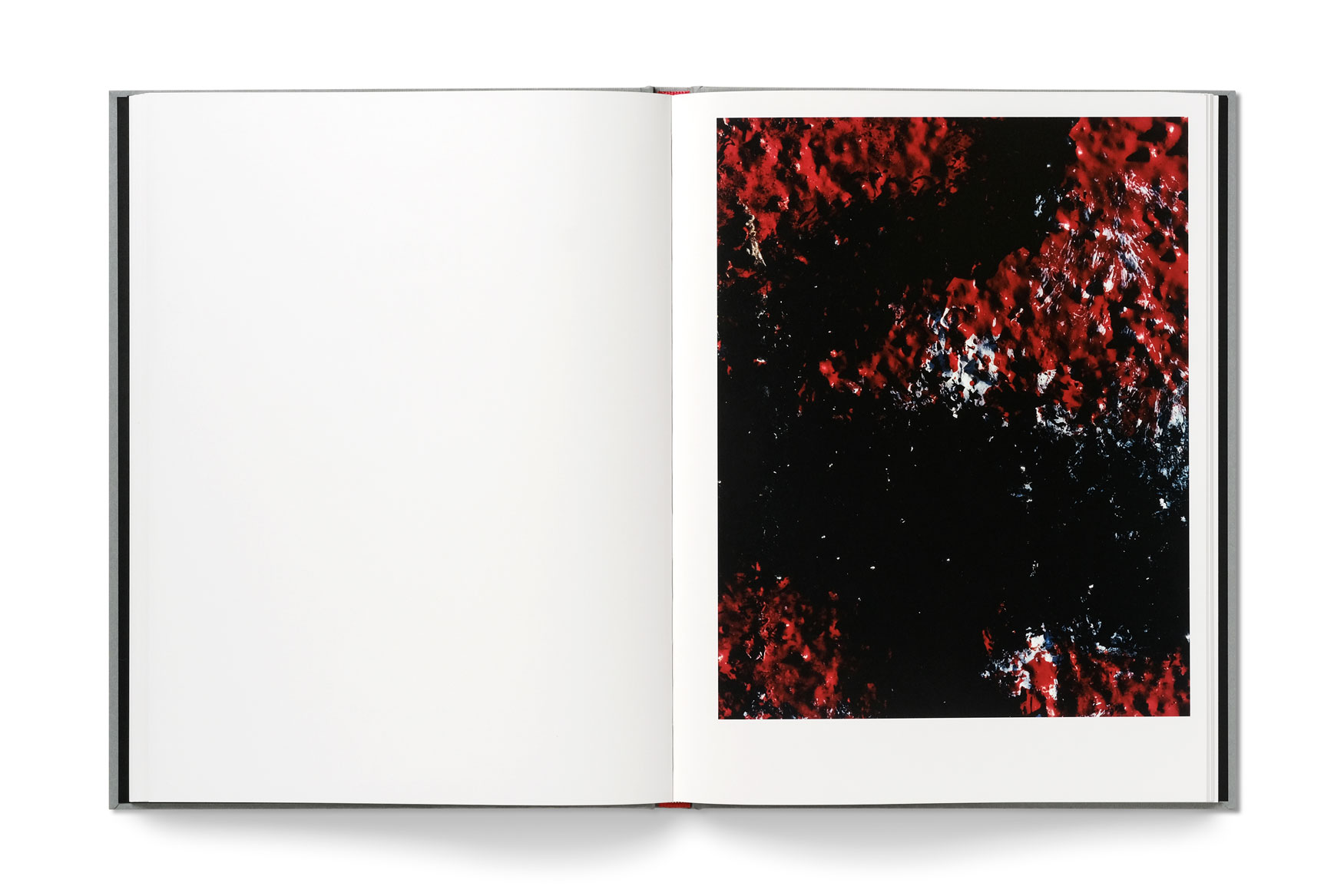

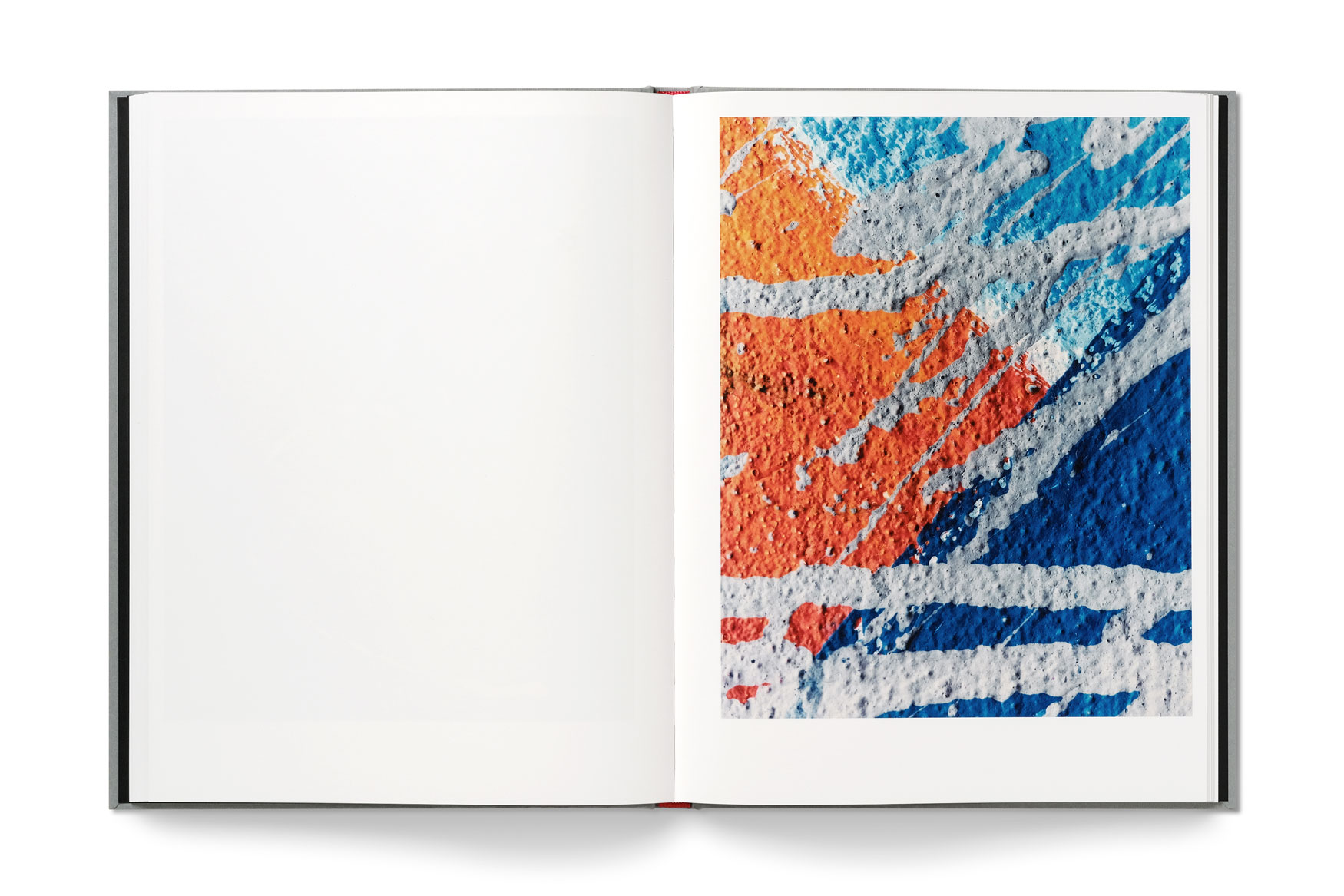

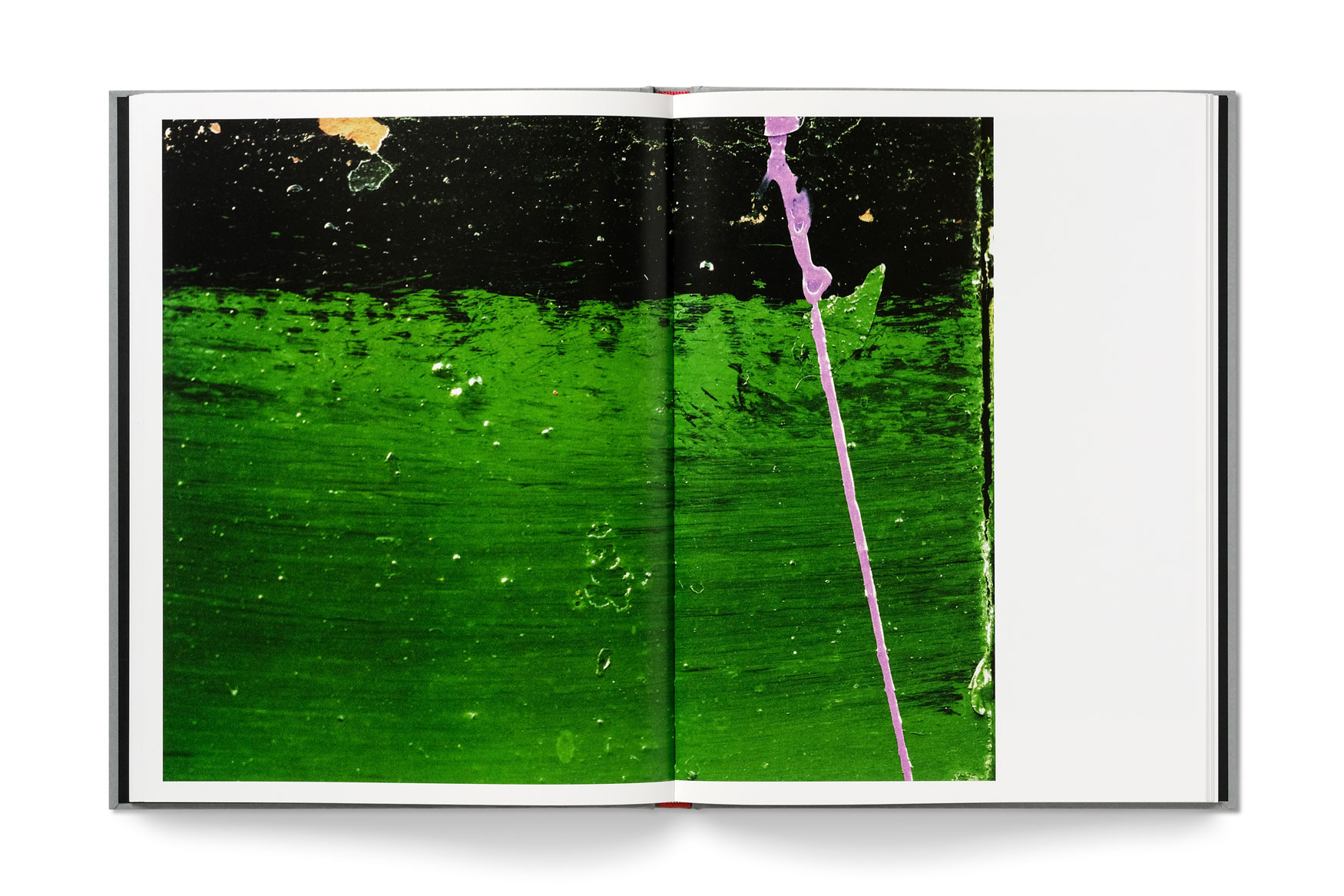

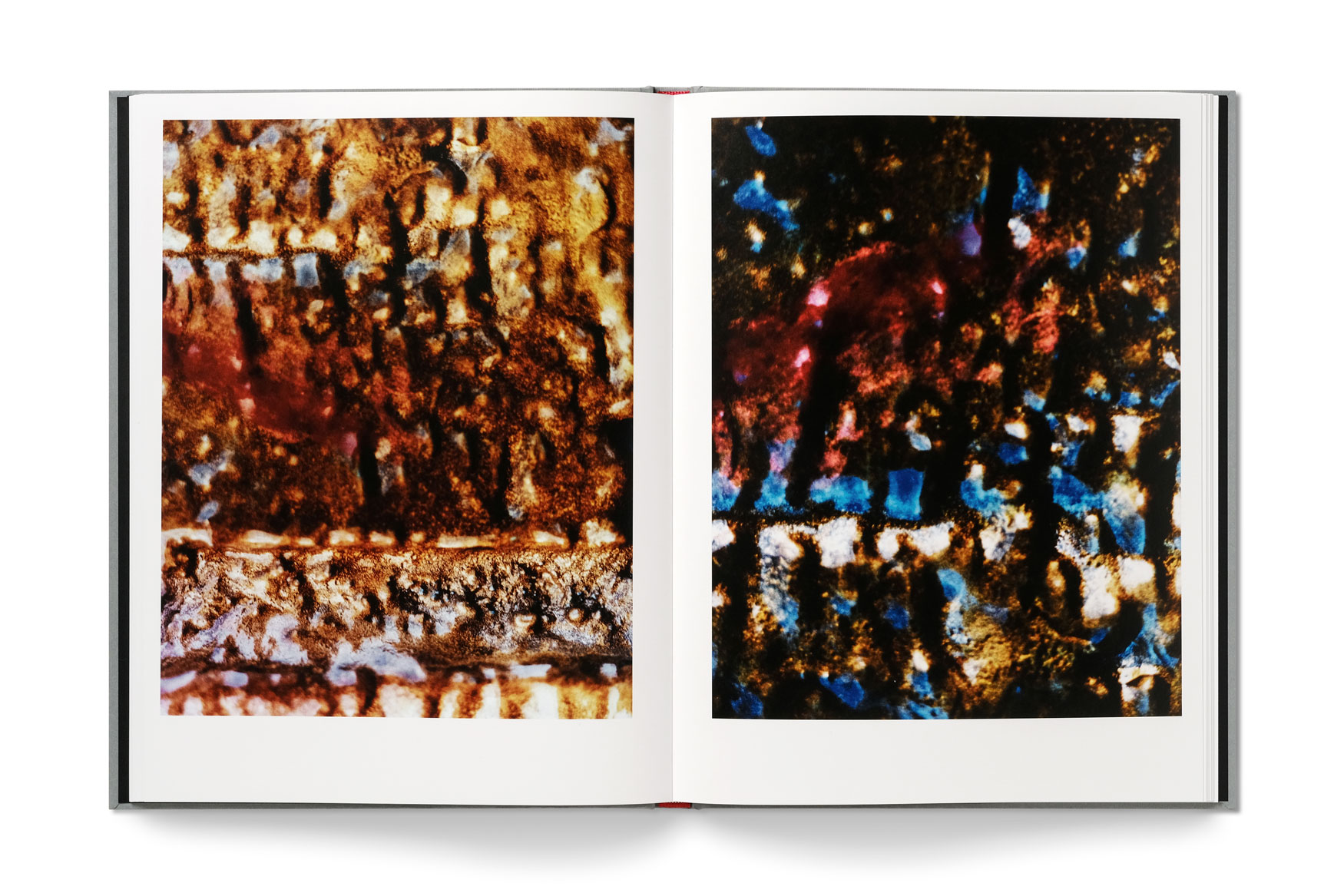

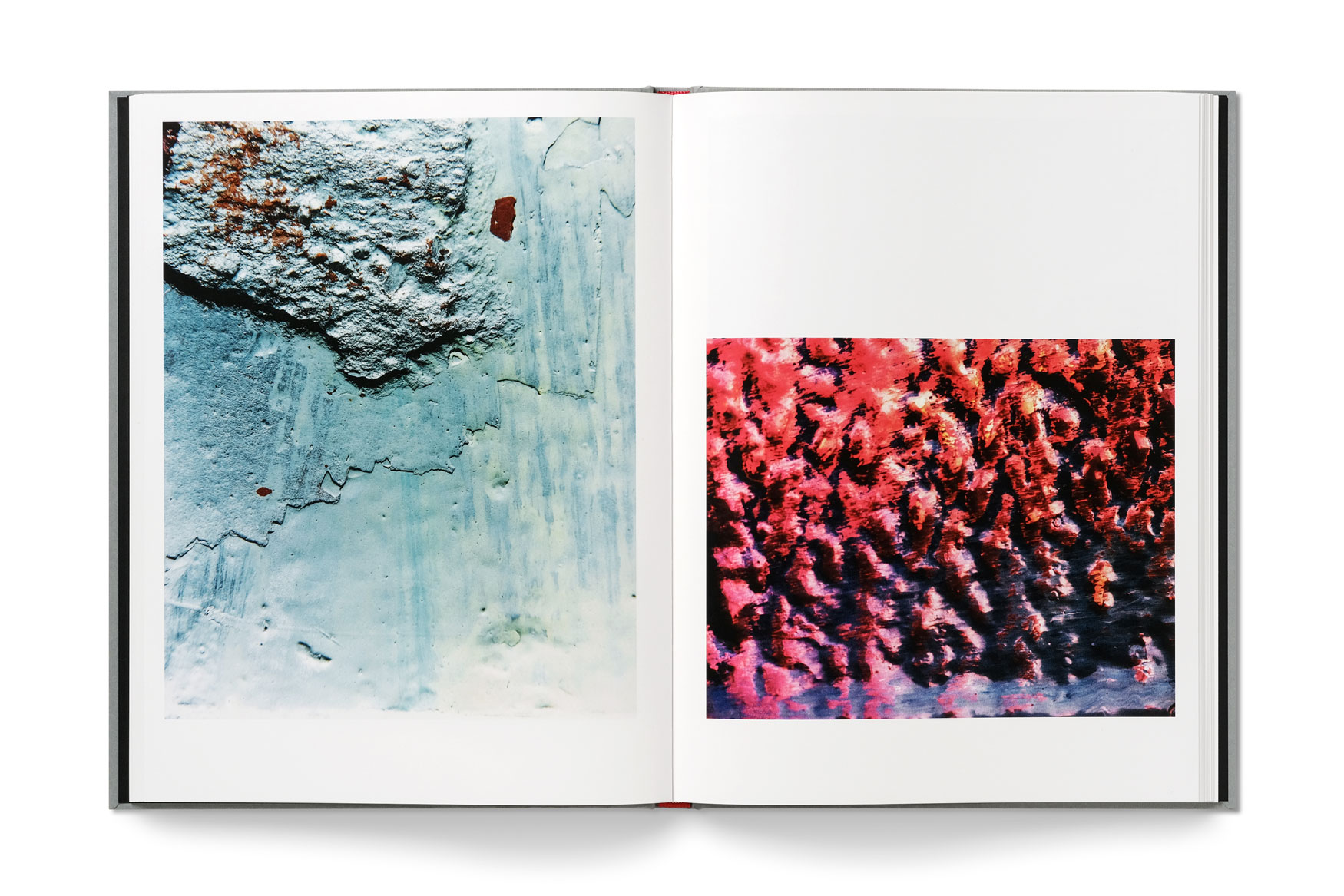

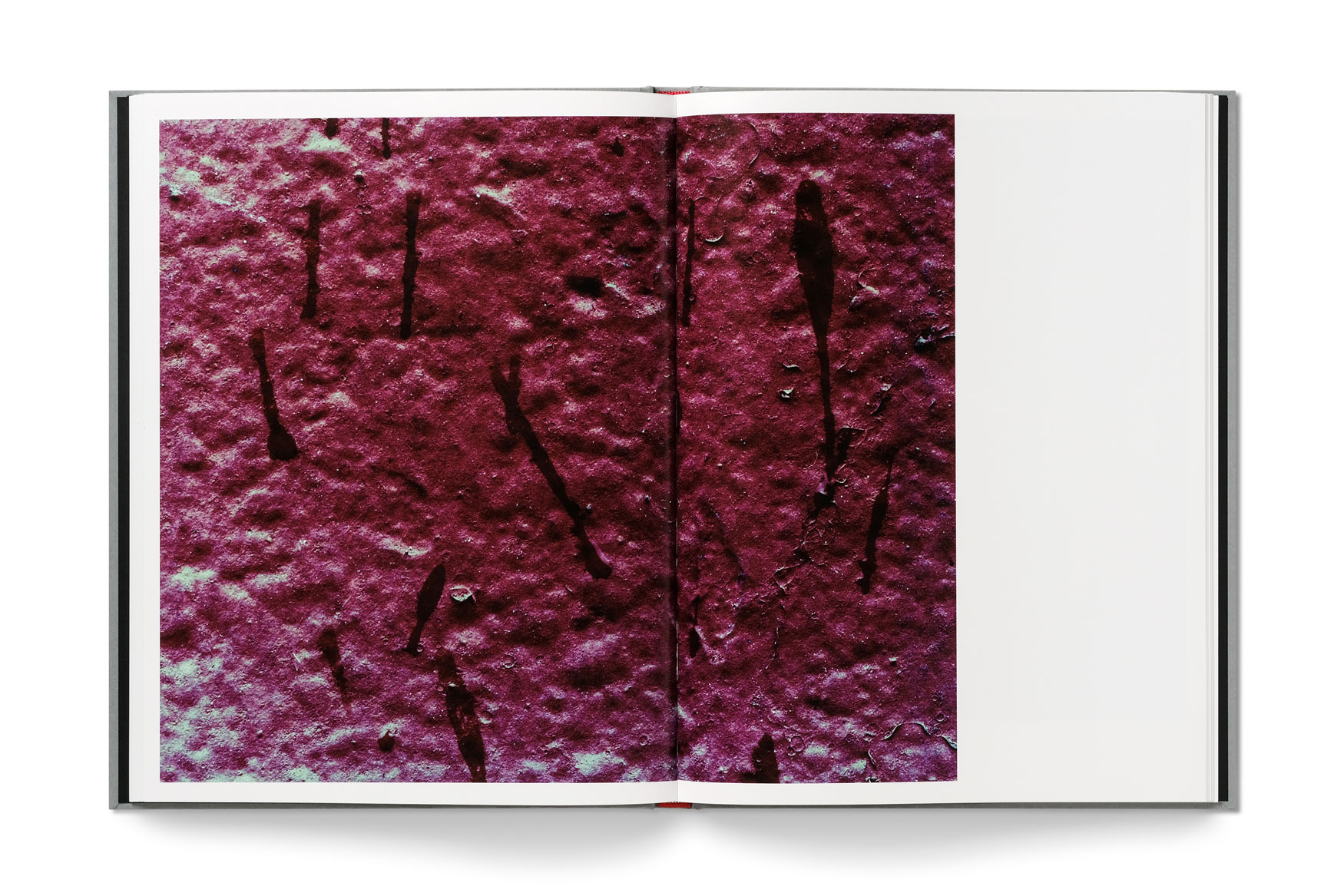

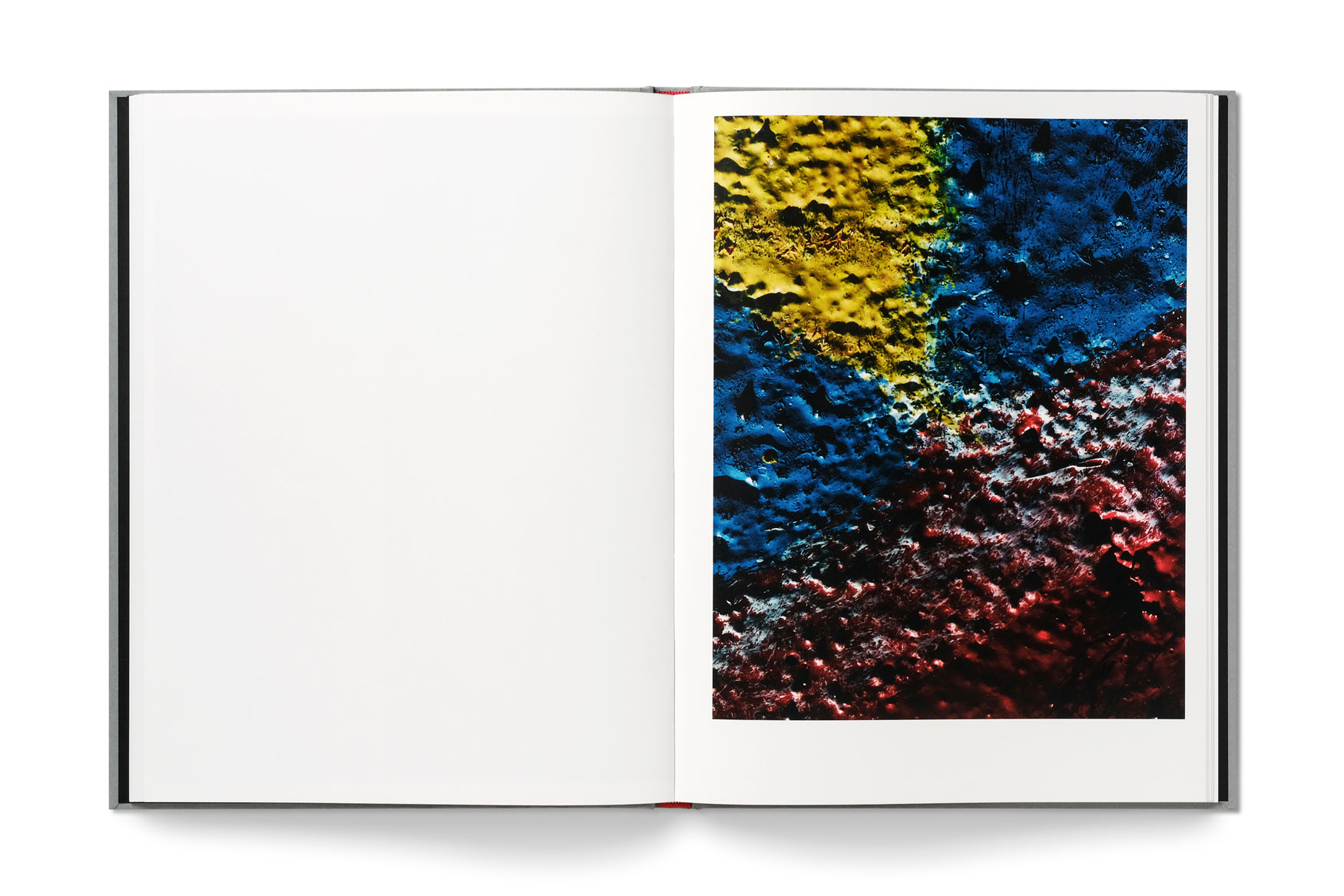

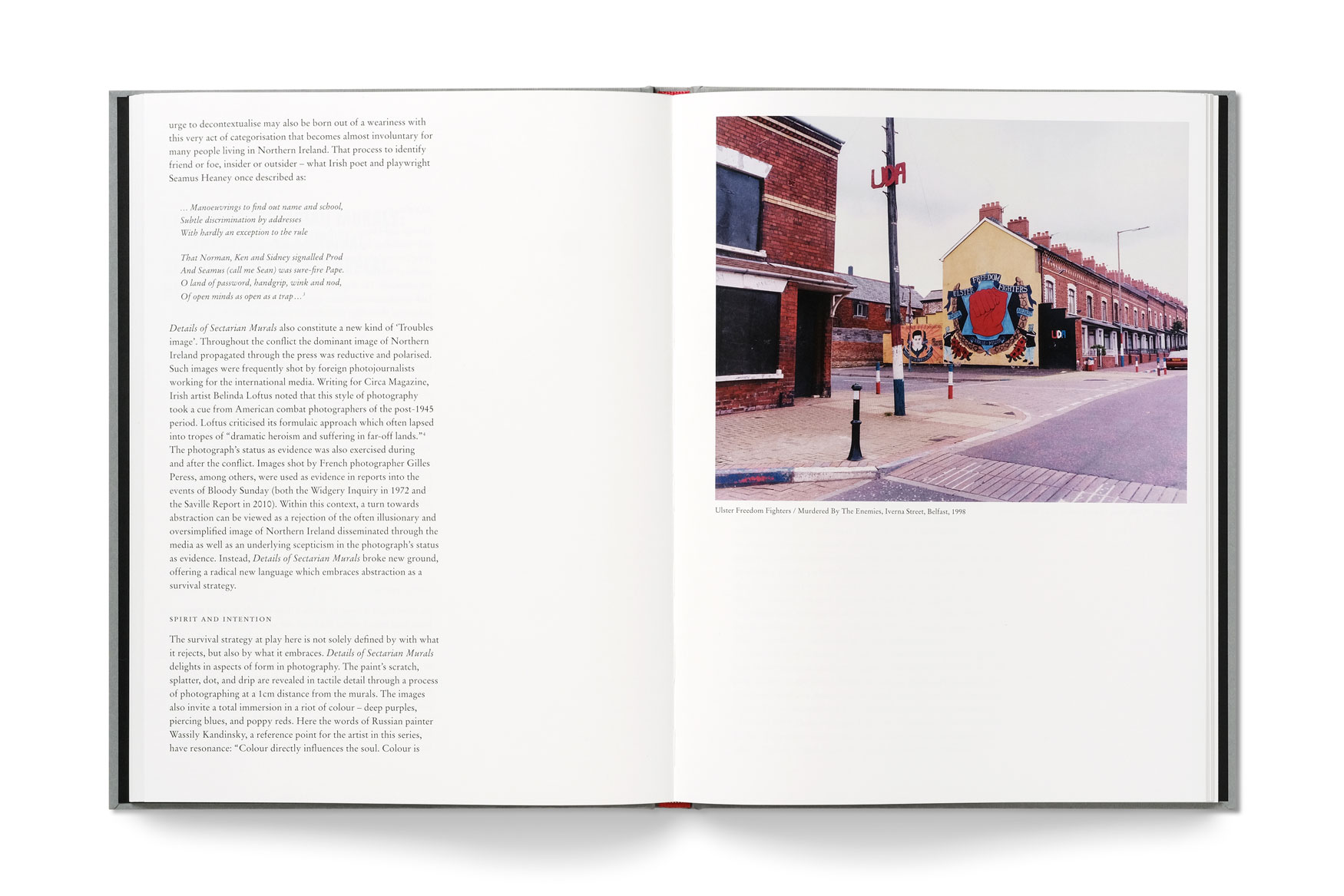

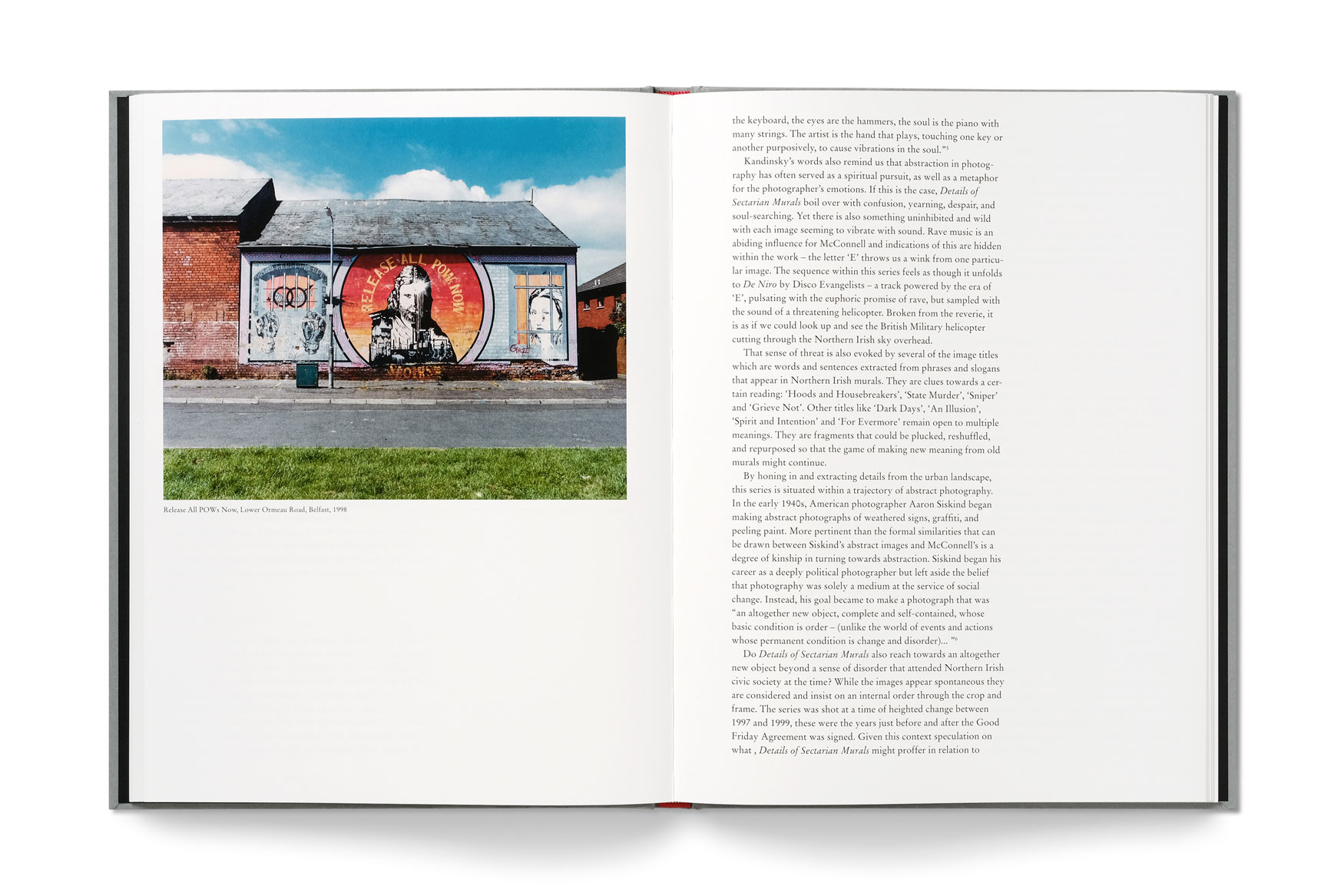

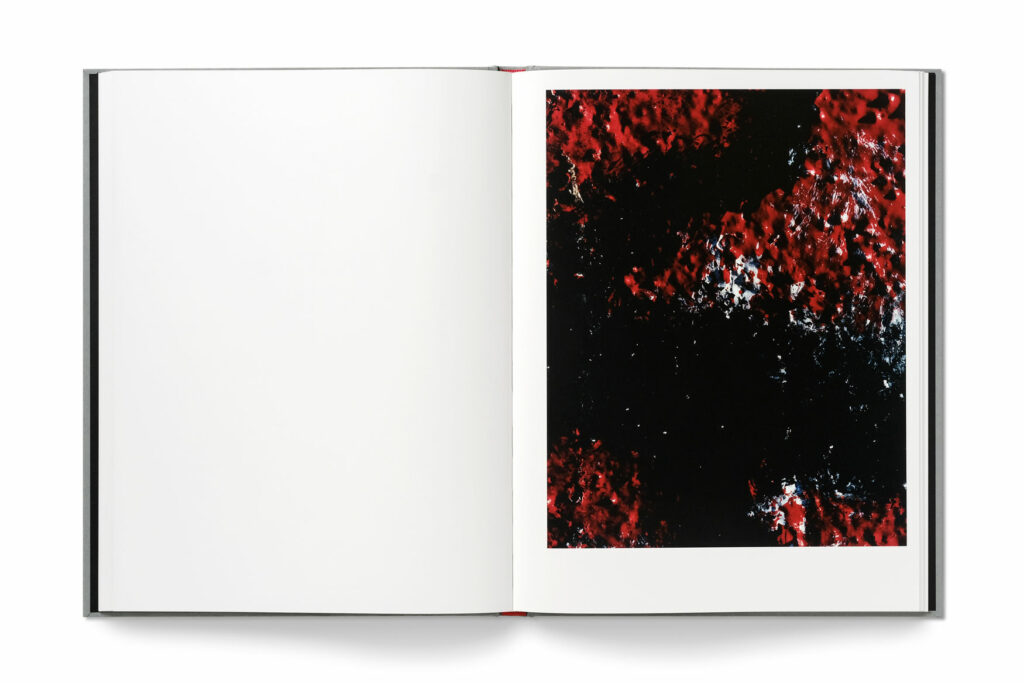

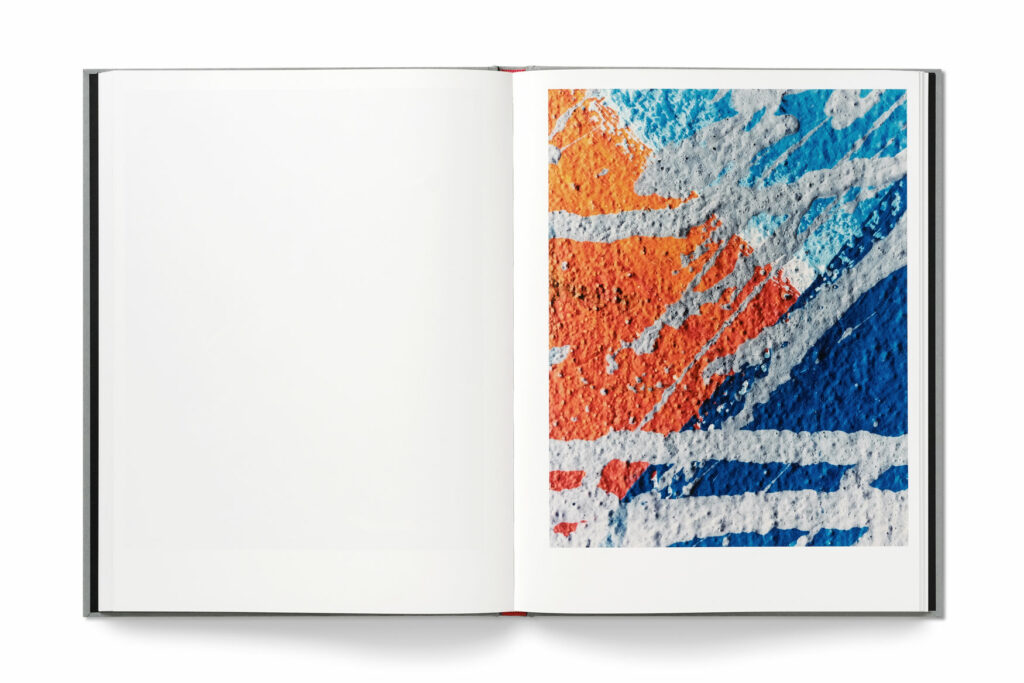

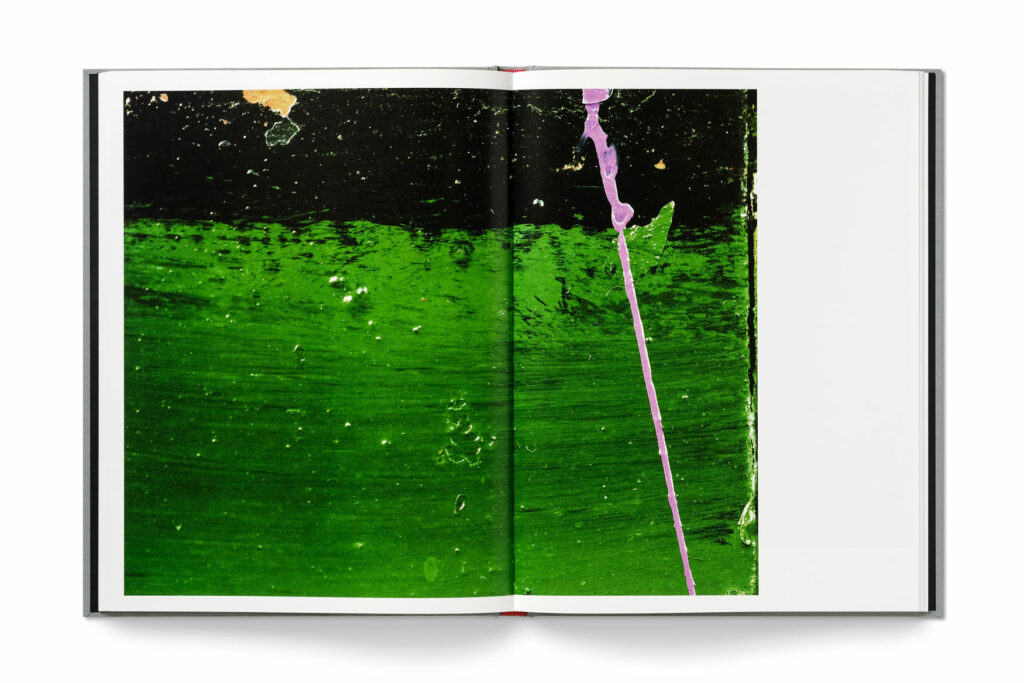

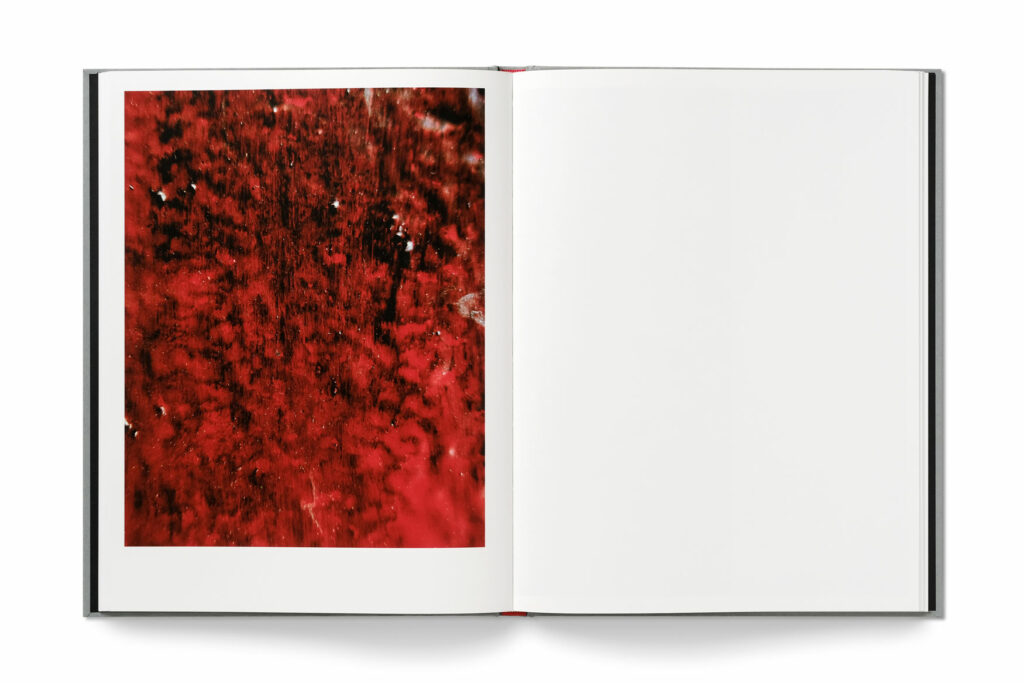

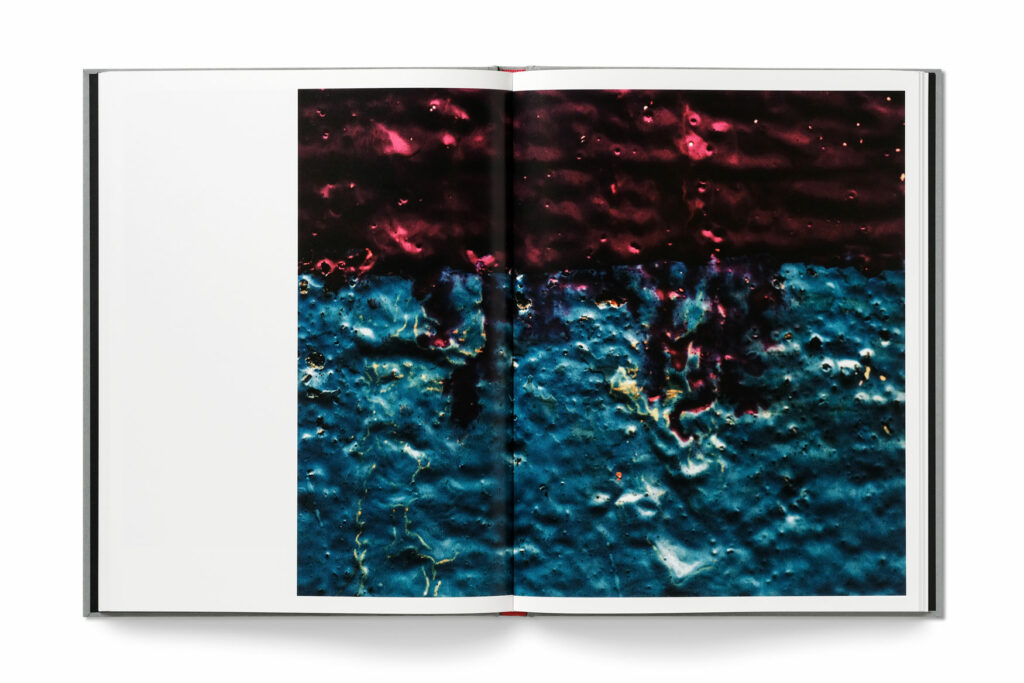

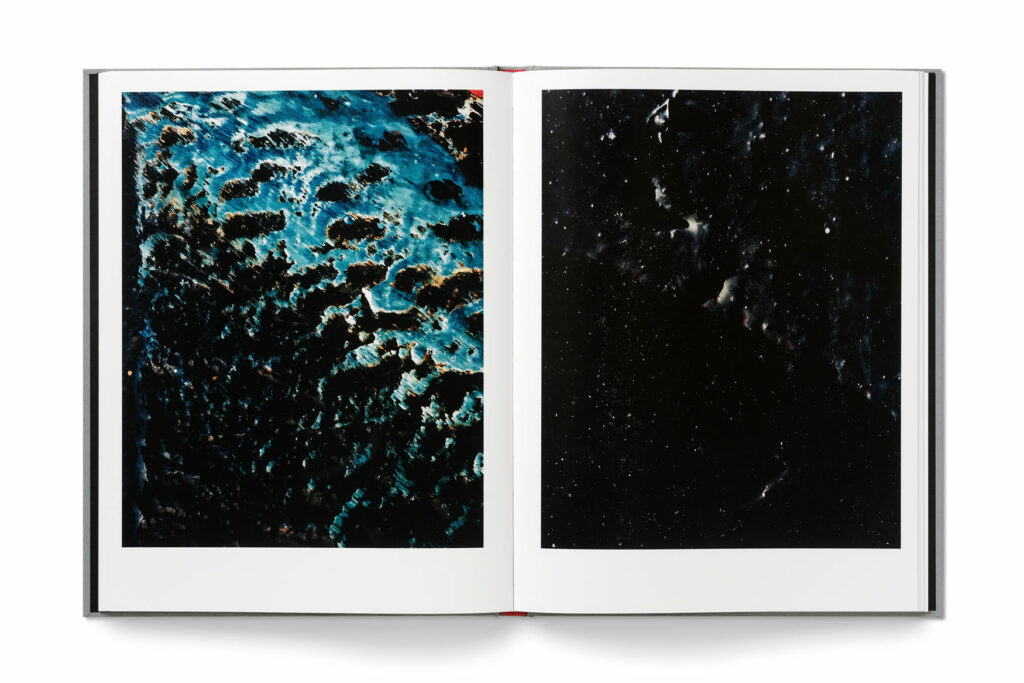

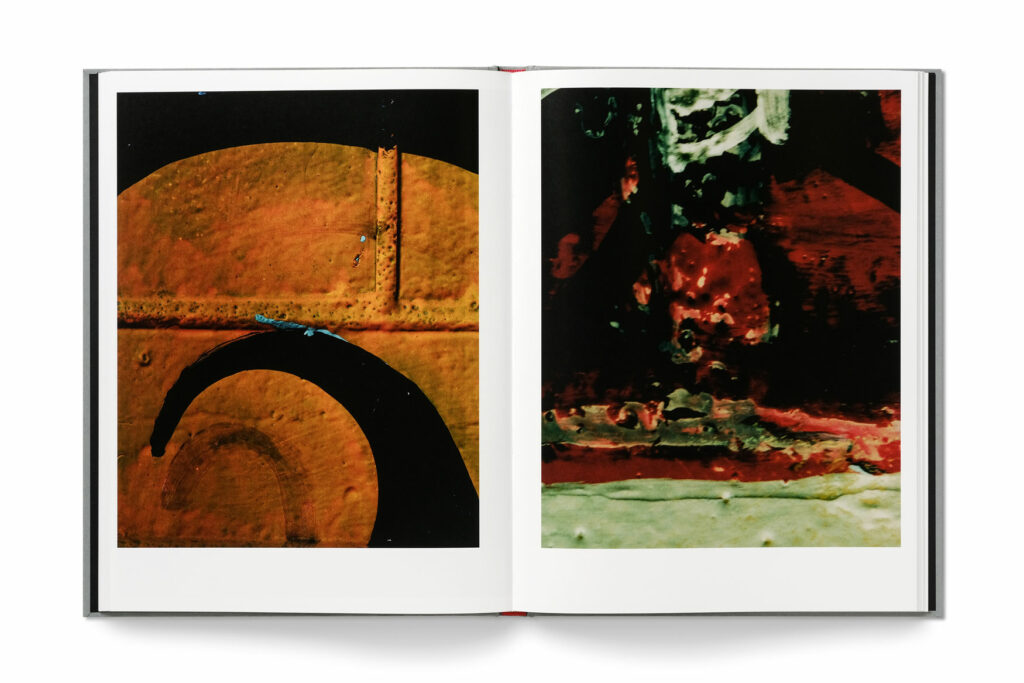

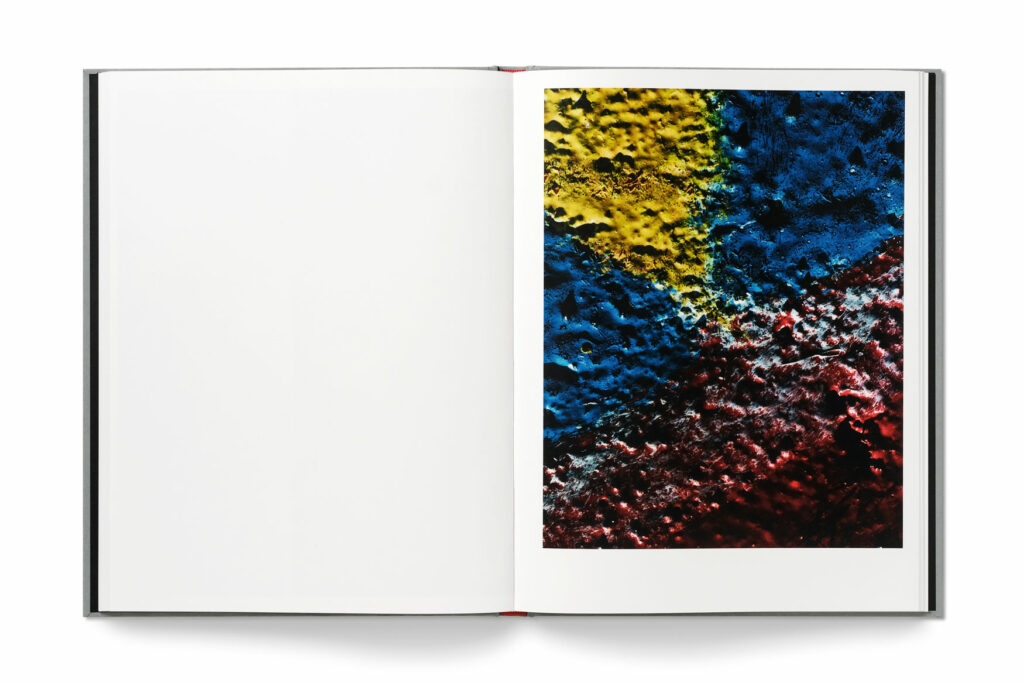

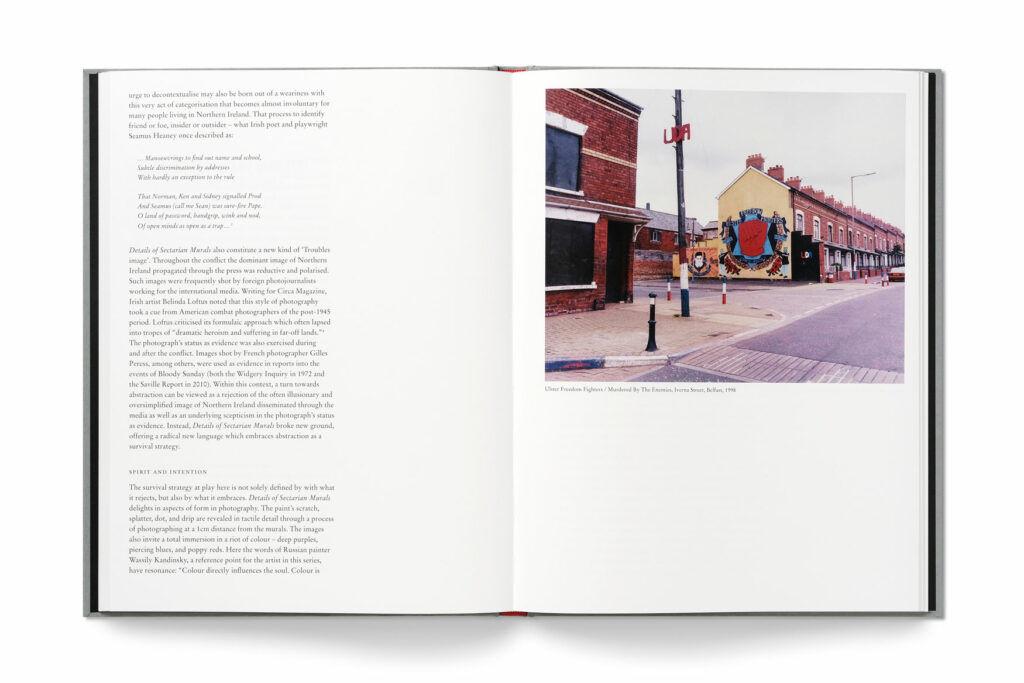

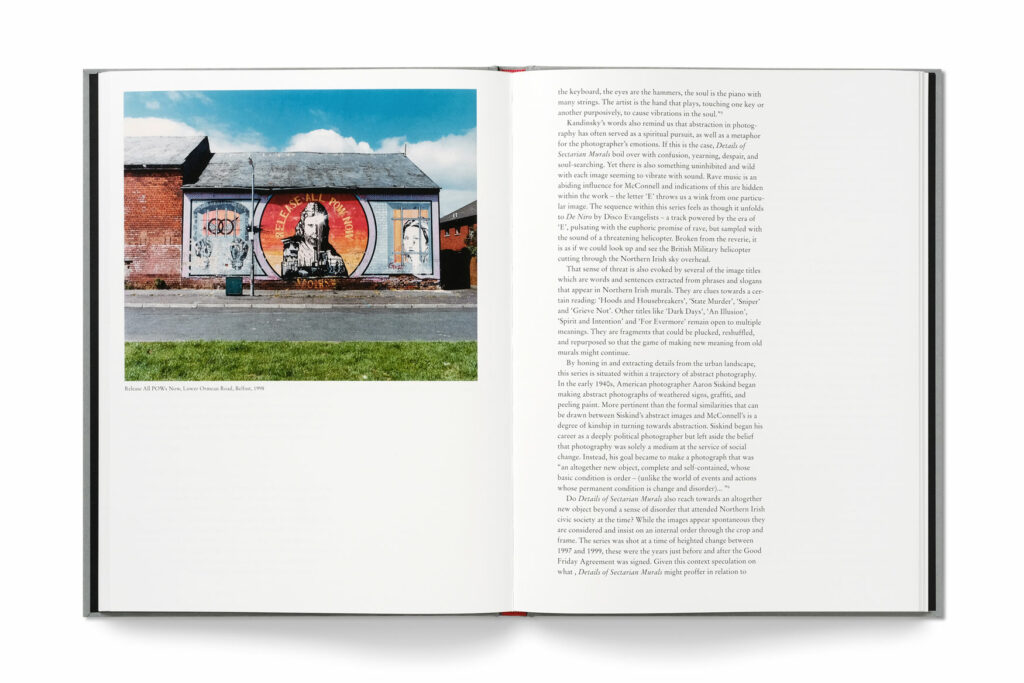

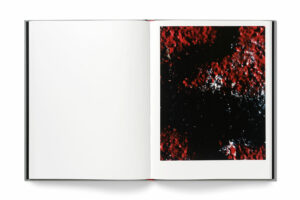

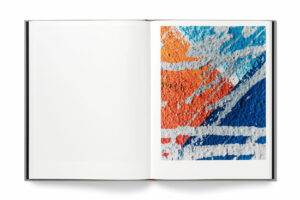

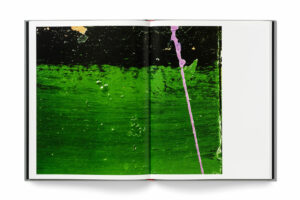

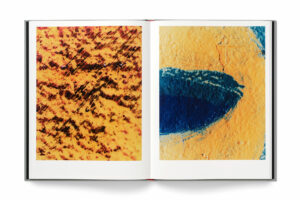

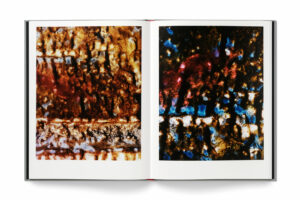

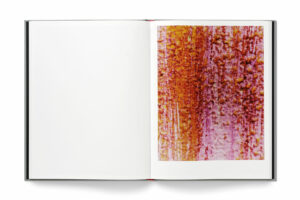

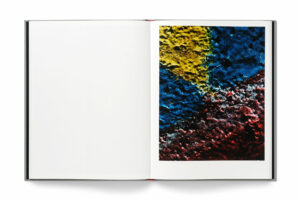

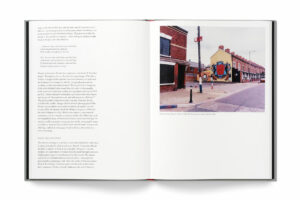

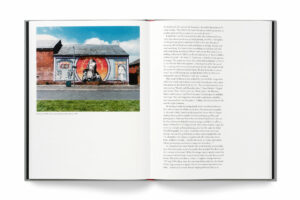

Orange and Green, lost in a mix of white, purple, black, blue, and red – colliding brushstrokes that amass to form a larger picture lying beyond the frame. During the Troubles, and still today, the streets of Northern Ireland[i] are a canvas onto which allegiances are projected. The Republic of Ireland’s tricolour and the Union Jack are ubiquitous. Never confined to flagpoles alone, the colours of these flags extend to the urban fabric of the city – to street kerbs, lampposts, and roundabouts. By far the most distinctive displays of allegiance are the murals. Often painted onto the gable end of houses, they are spectacular territorial indicators and boundary markers making plain the reality of segregation.

Murals originally appeared in the early 20th century as part of an assertion of Protestant people’s sense of British identity. However, the practice of mural painting was stifled within the Catholic community. In the 1960s this was challenged by the Northern Irish Civil Rights Movement. The civil rights campaign was centred on securing equal access to housing and employment for the Catholic community, but other activities in the public domain such as parades and mural painting were also a focus.[ii] Irish Republican wall-paintings began to emerge in the late 1970s both as a vehicle to express identity and a means of consolidating support. The mainstream media also censored elements of Republican ideology, murals therefore became a method of expressing Republican goals to an international media where cameras were rolling, reporting on the conflict.

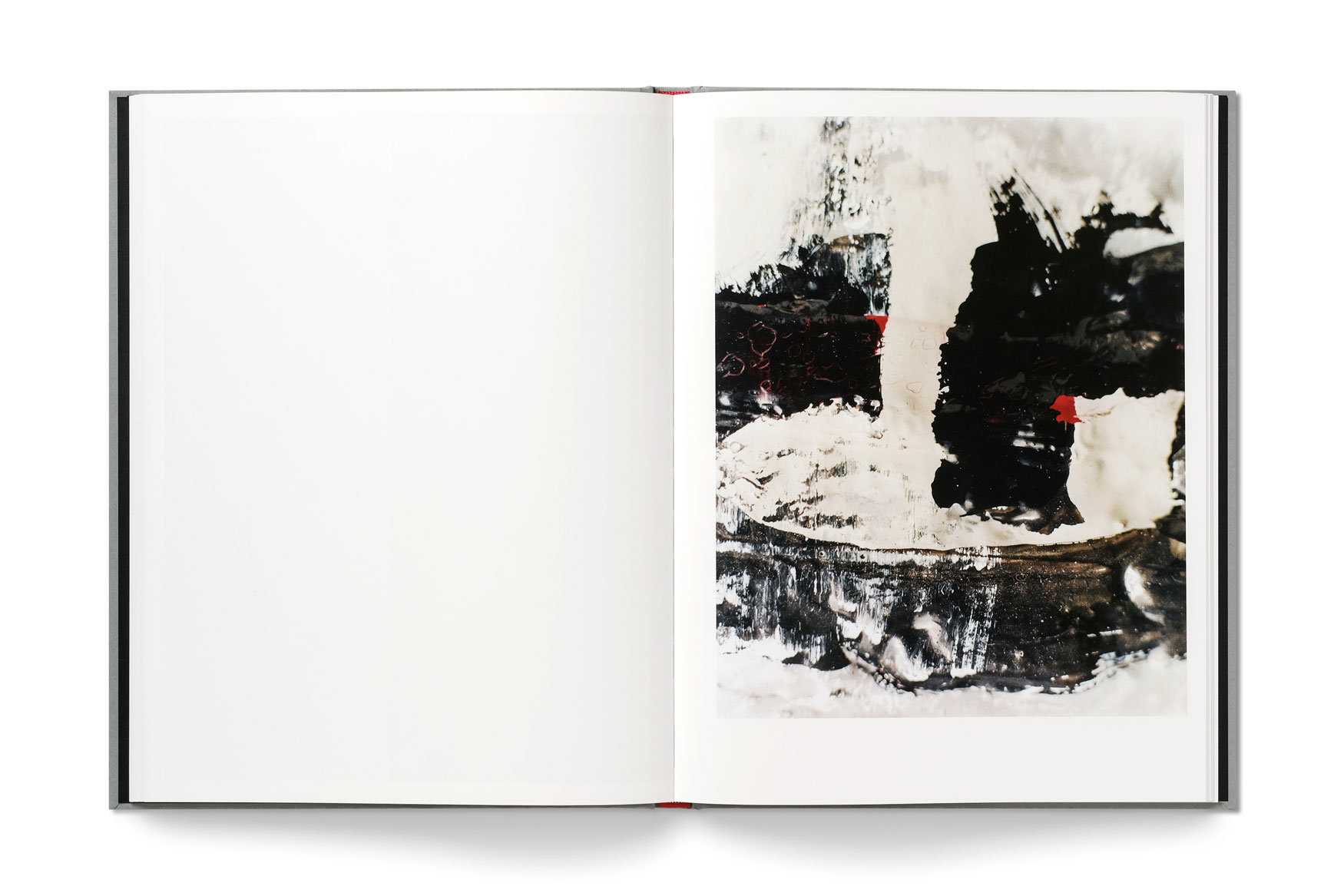

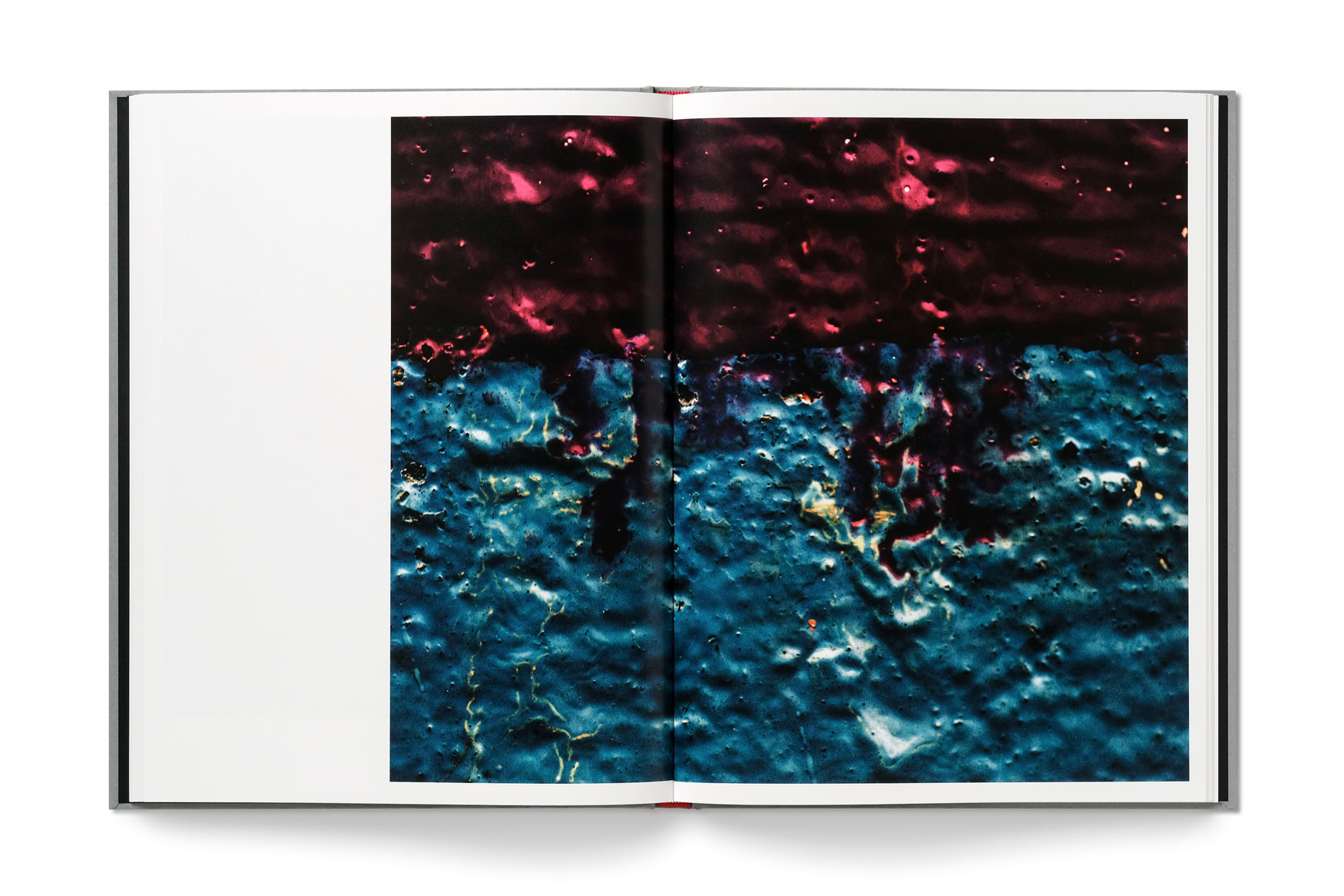

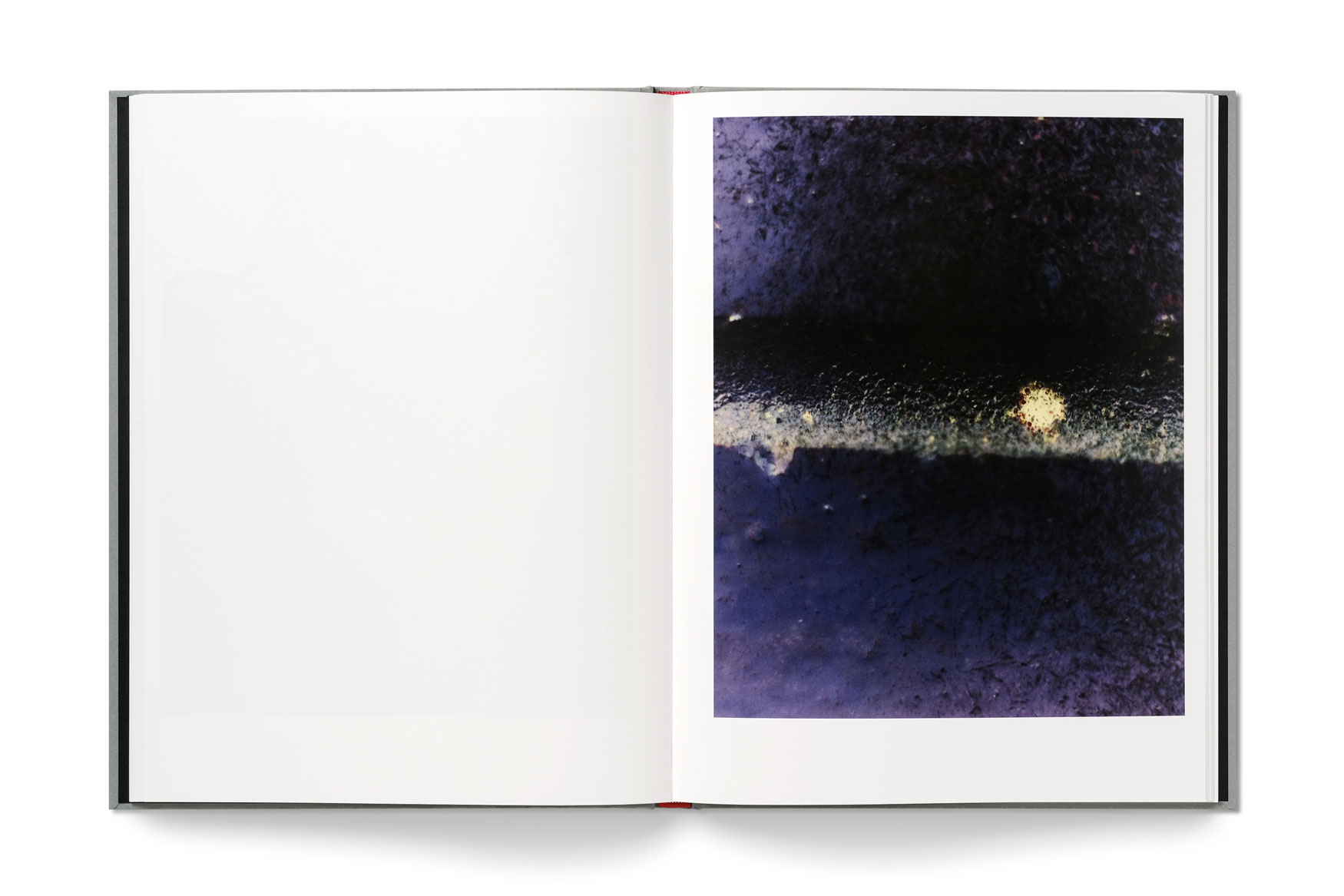

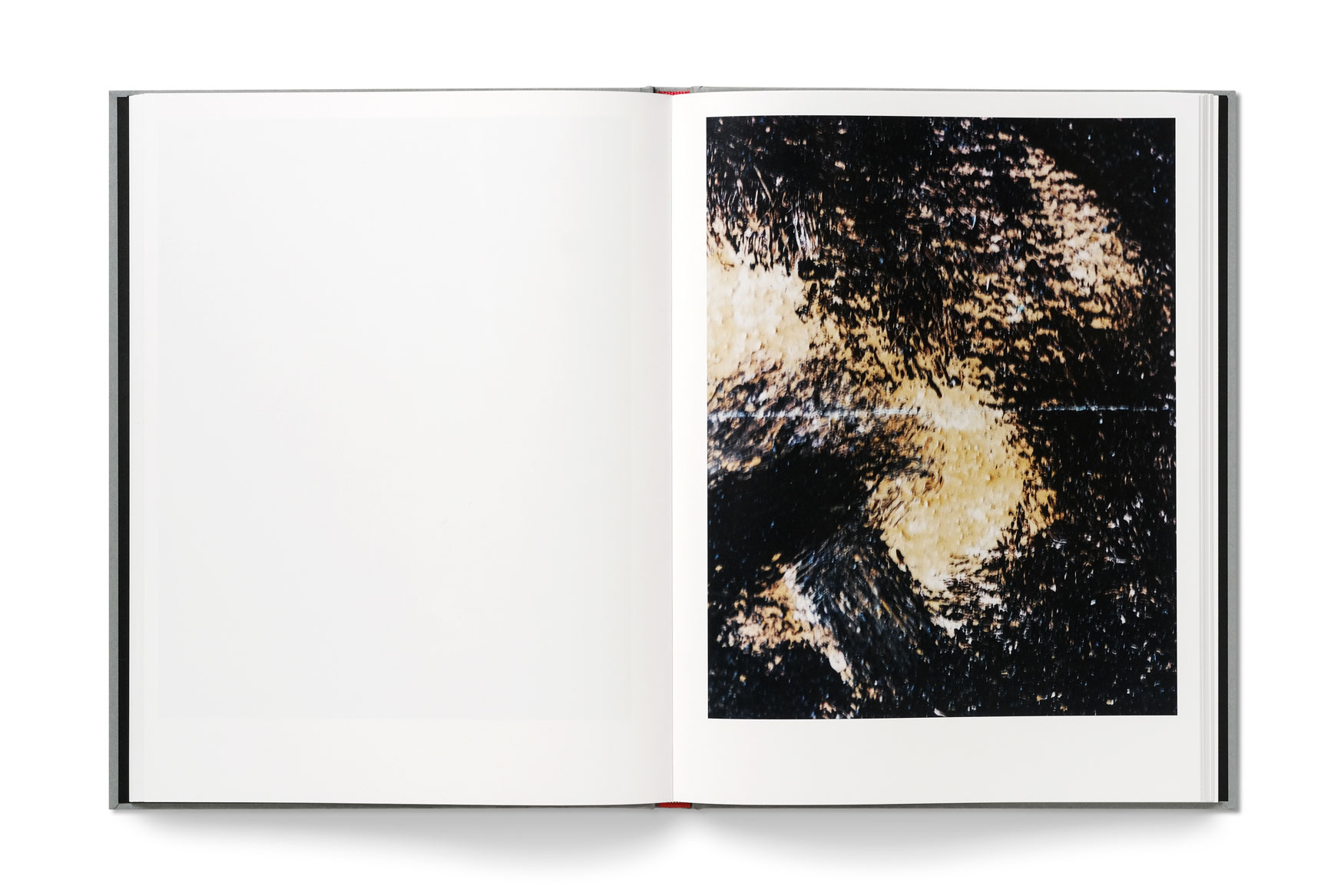

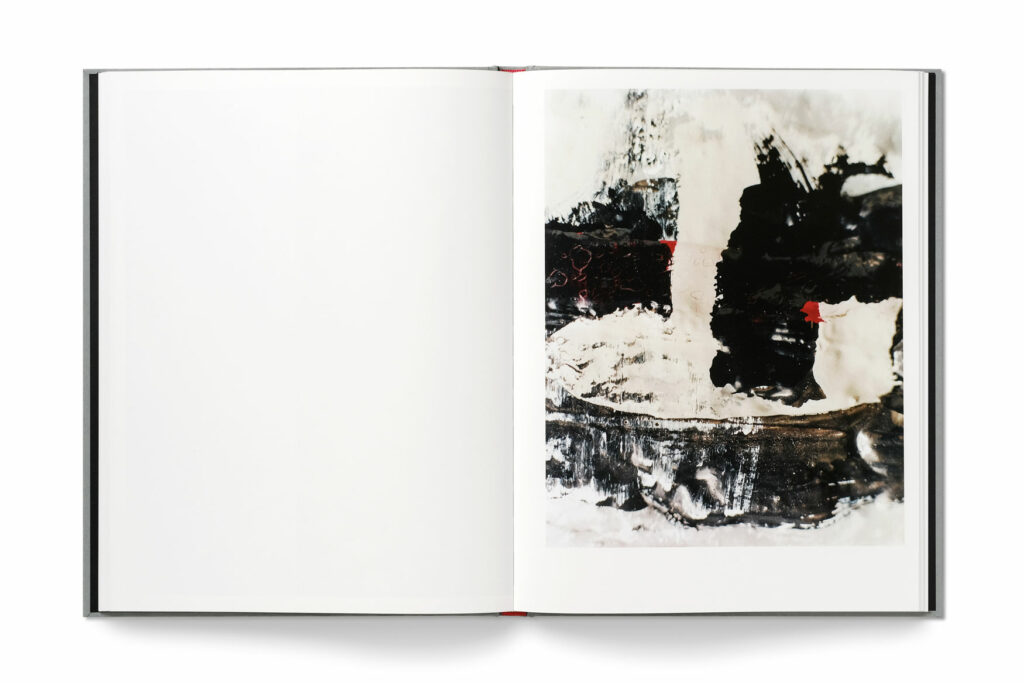

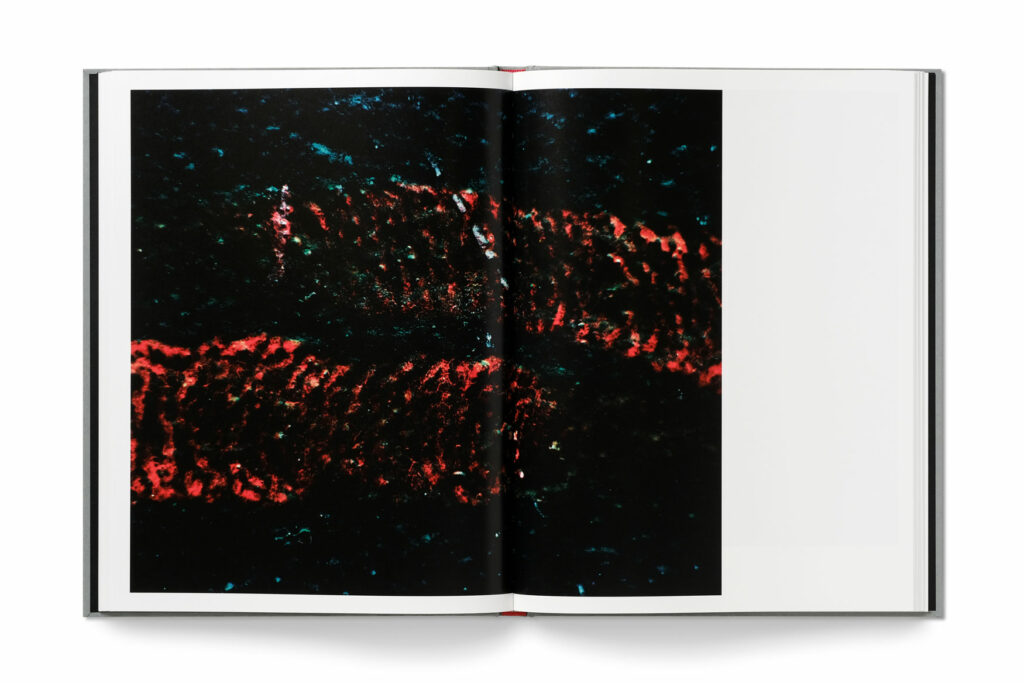

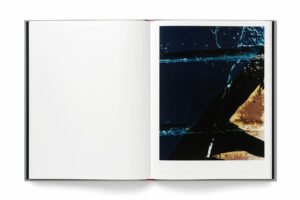

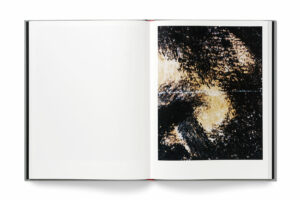

An Illusion

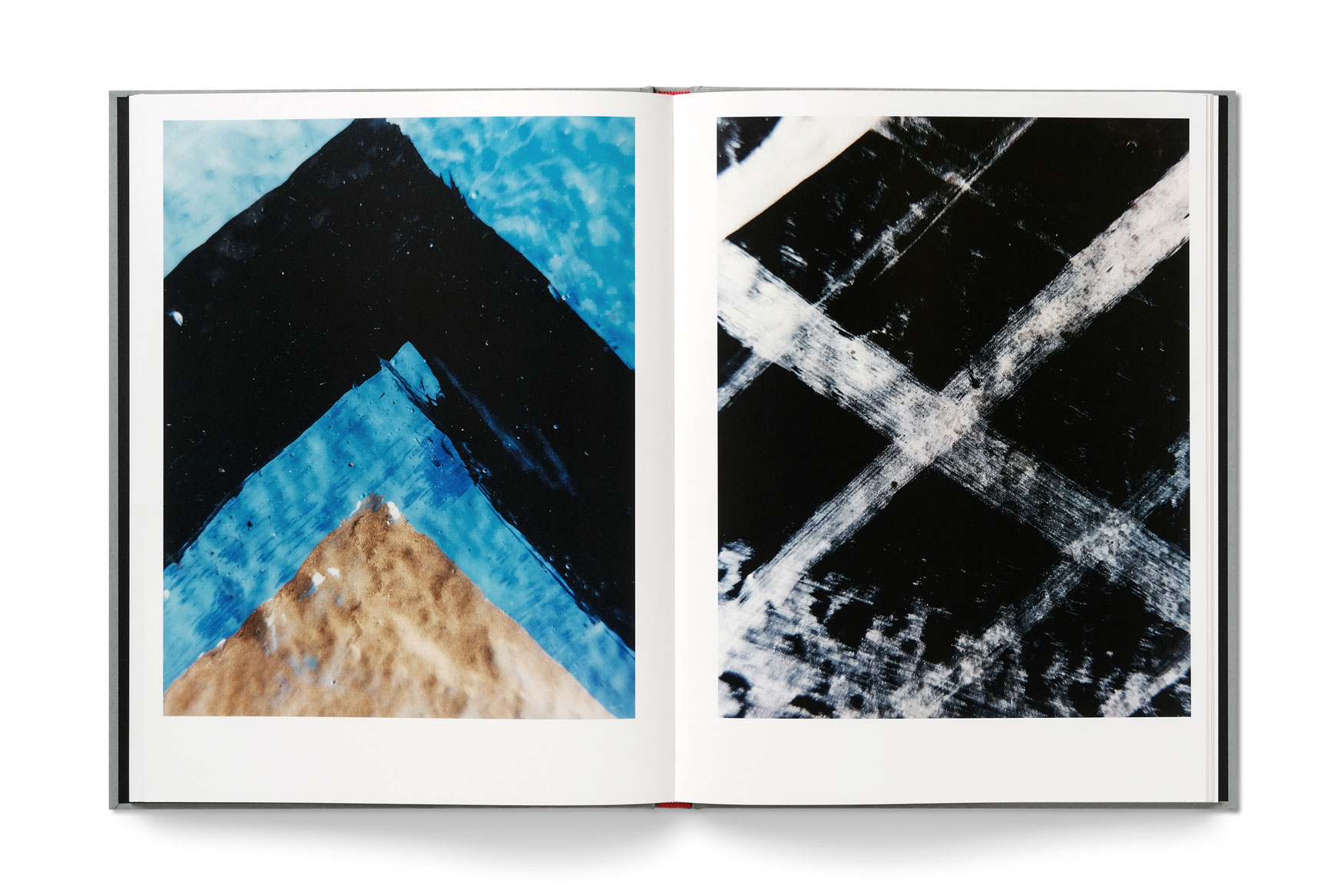

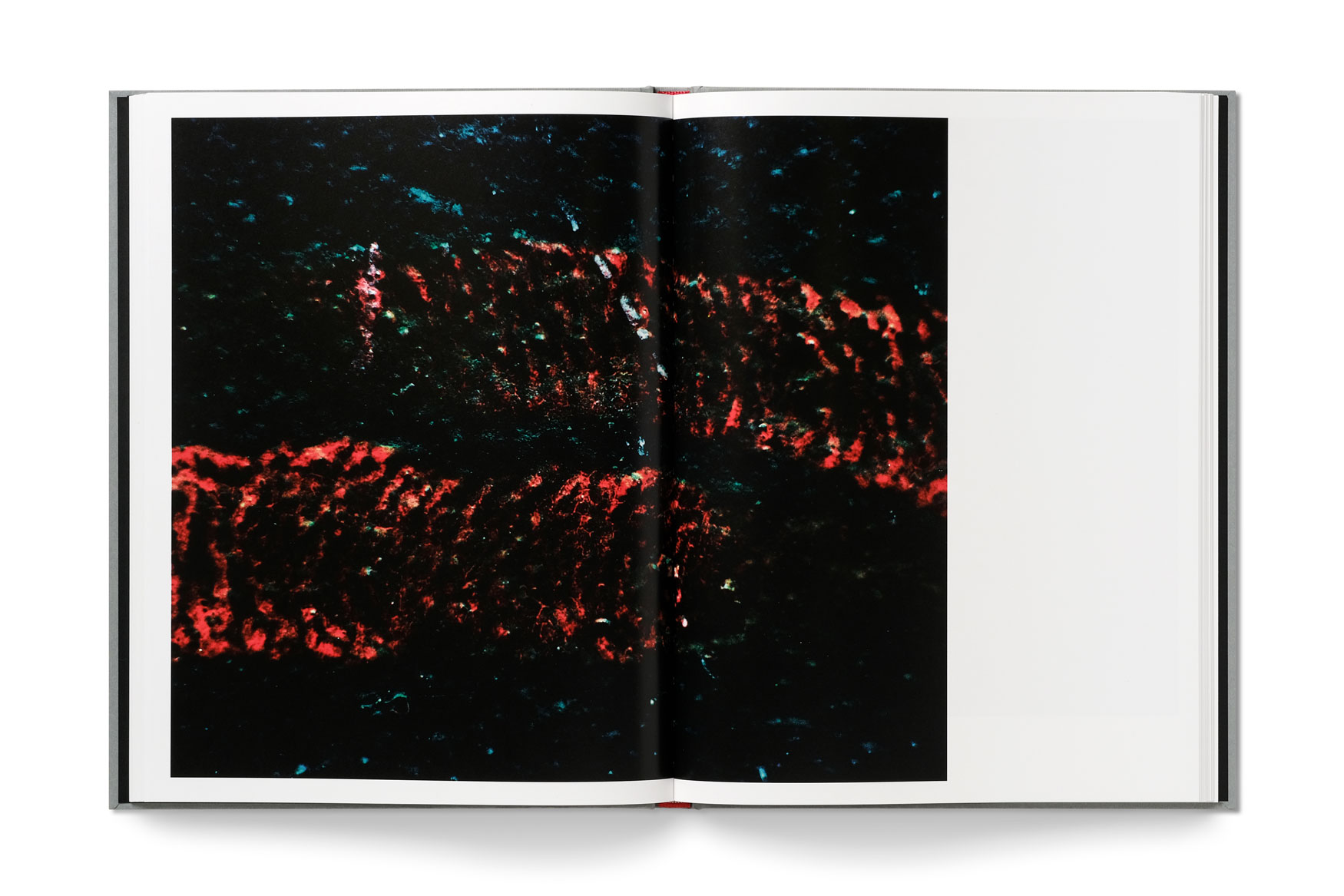

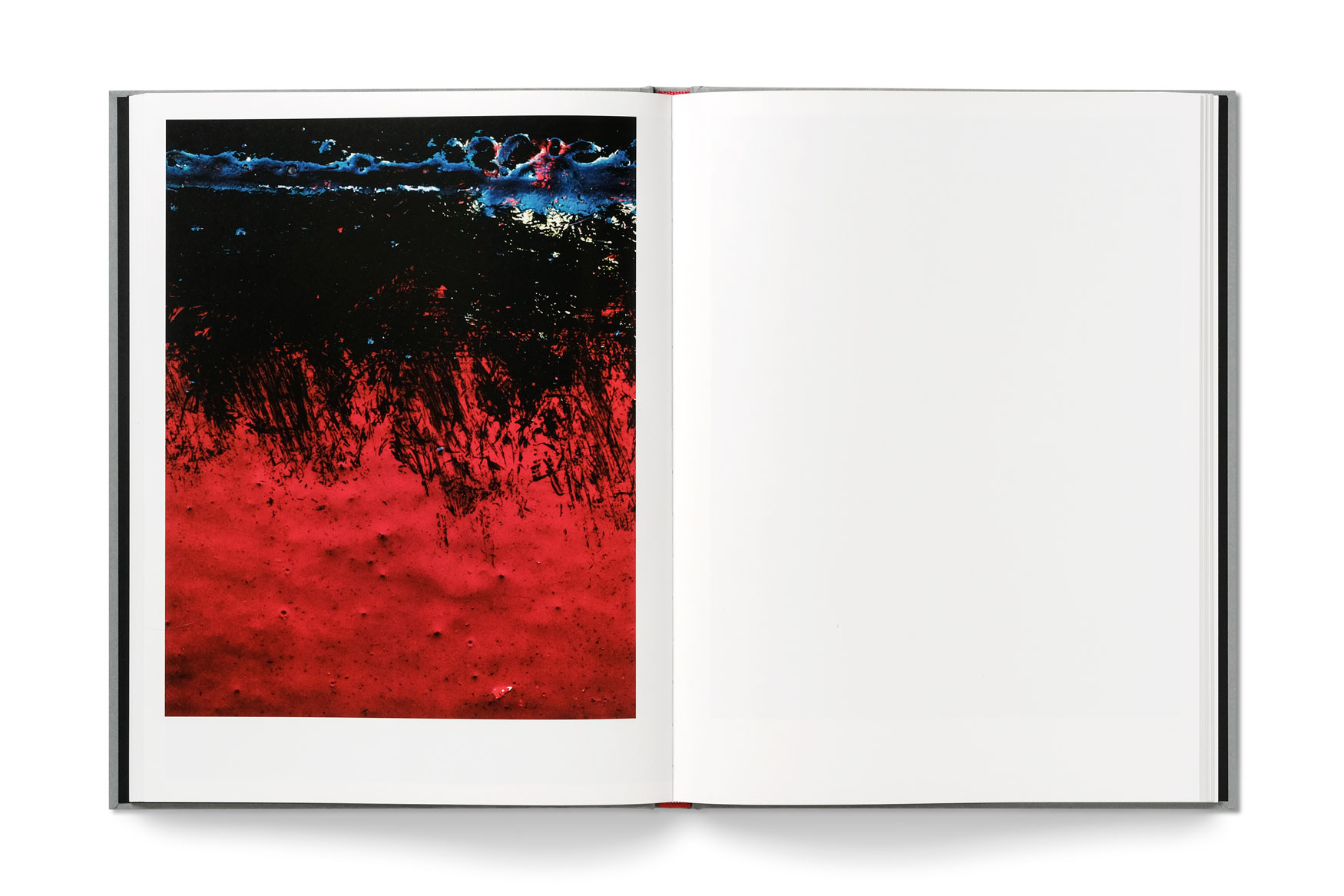

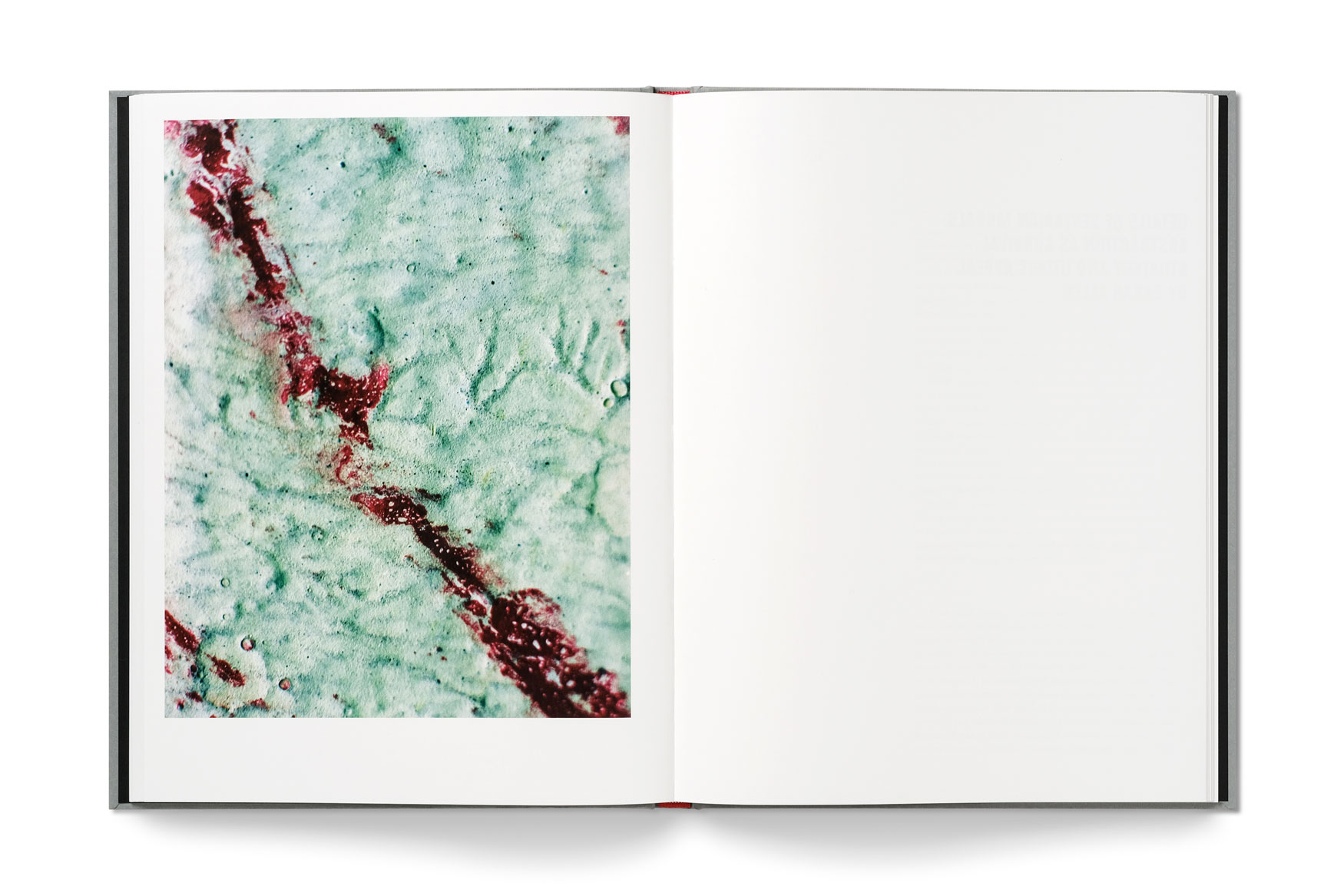

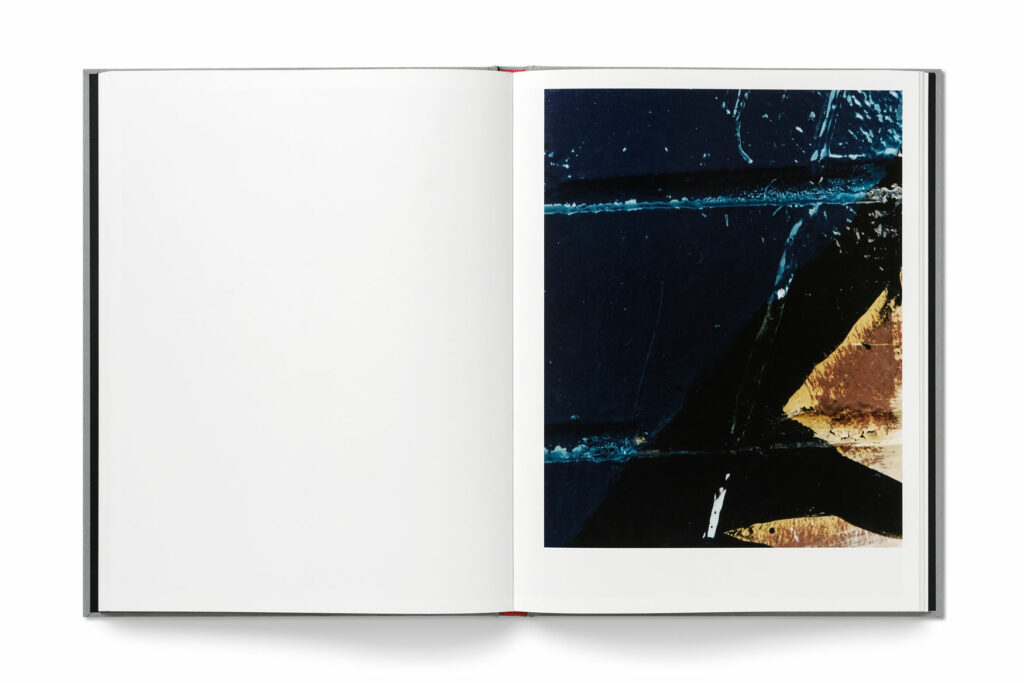

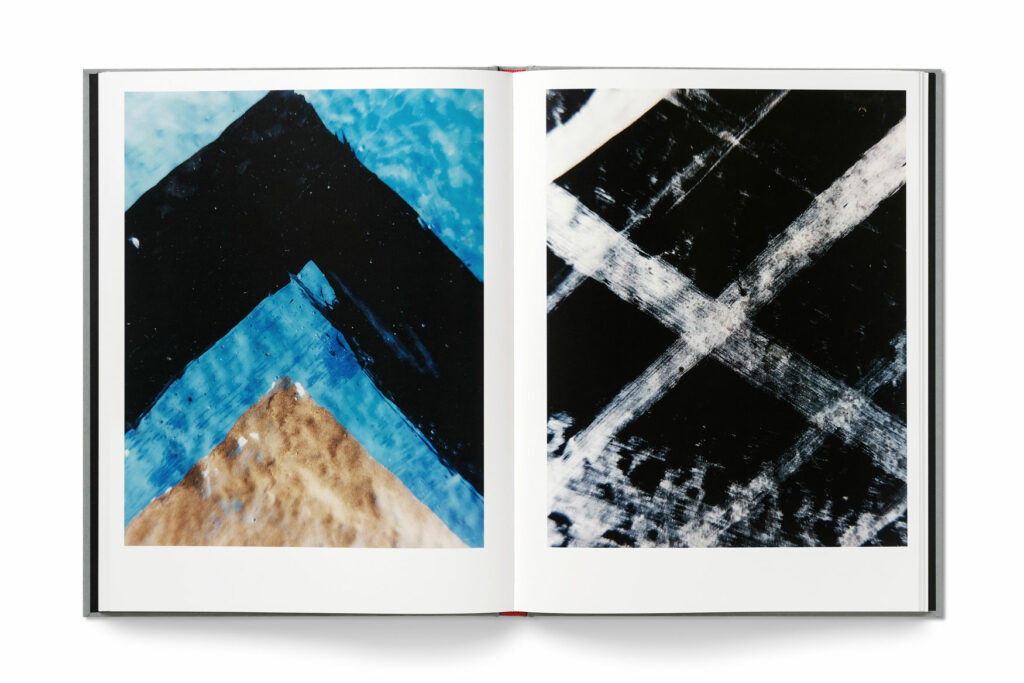

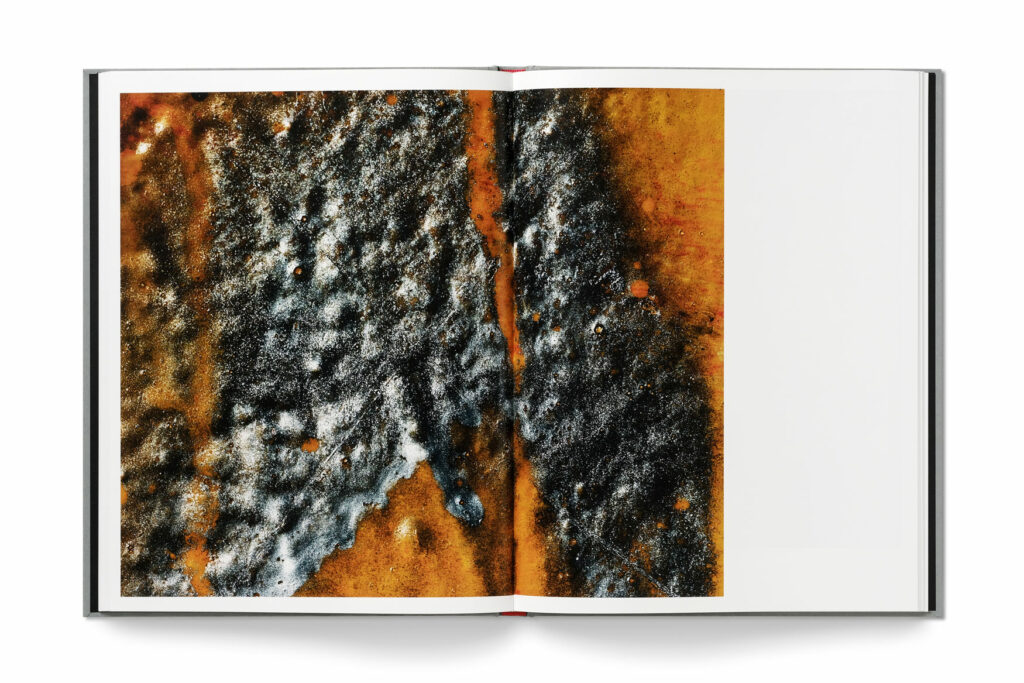

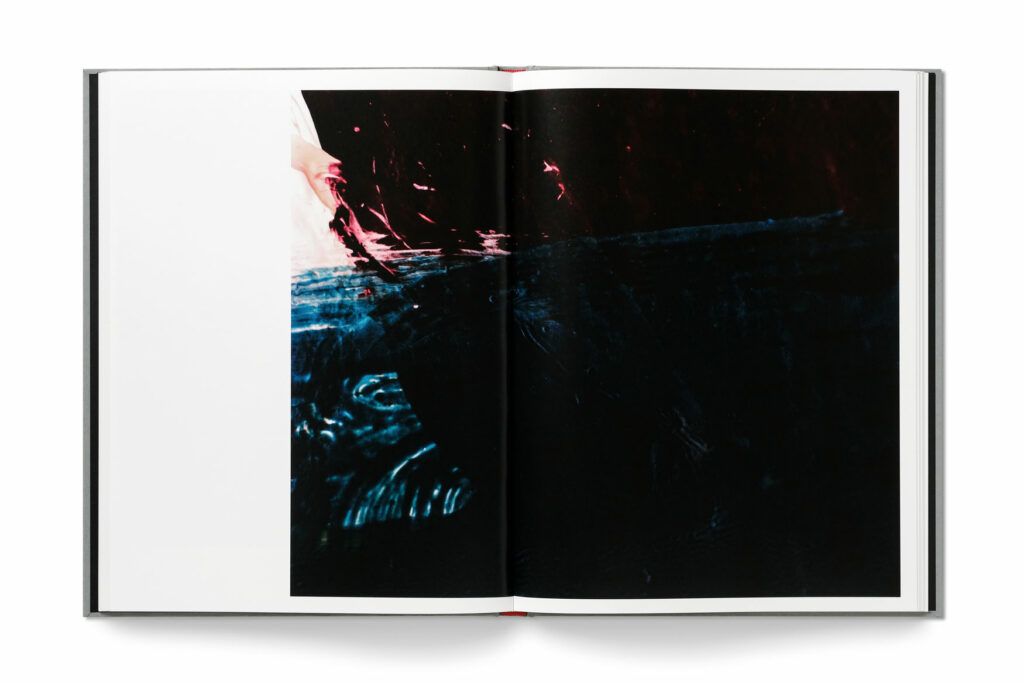

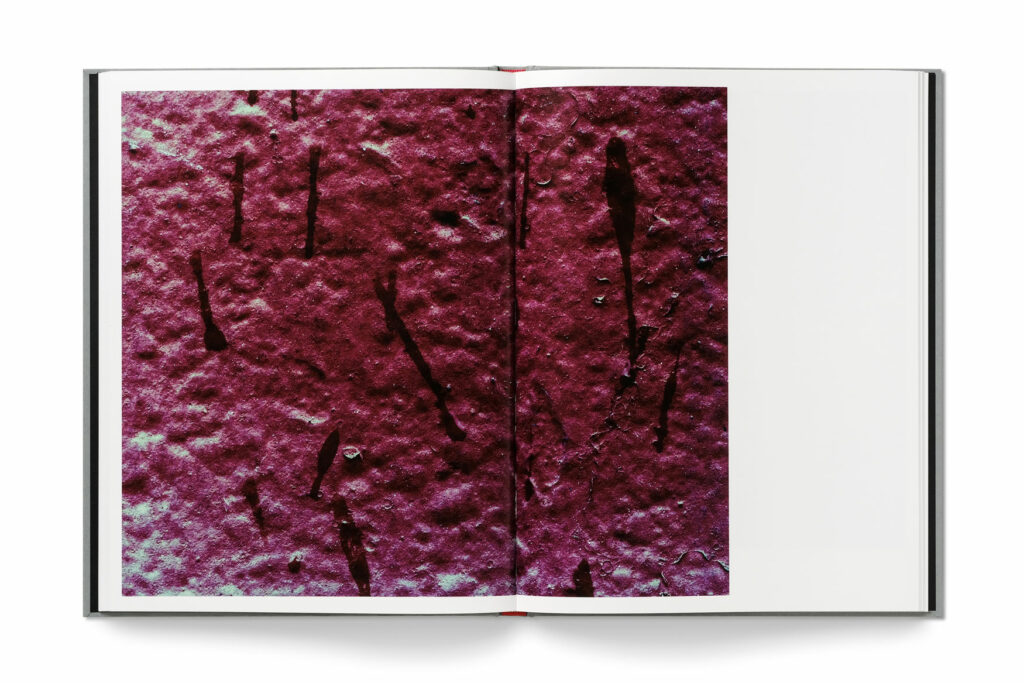

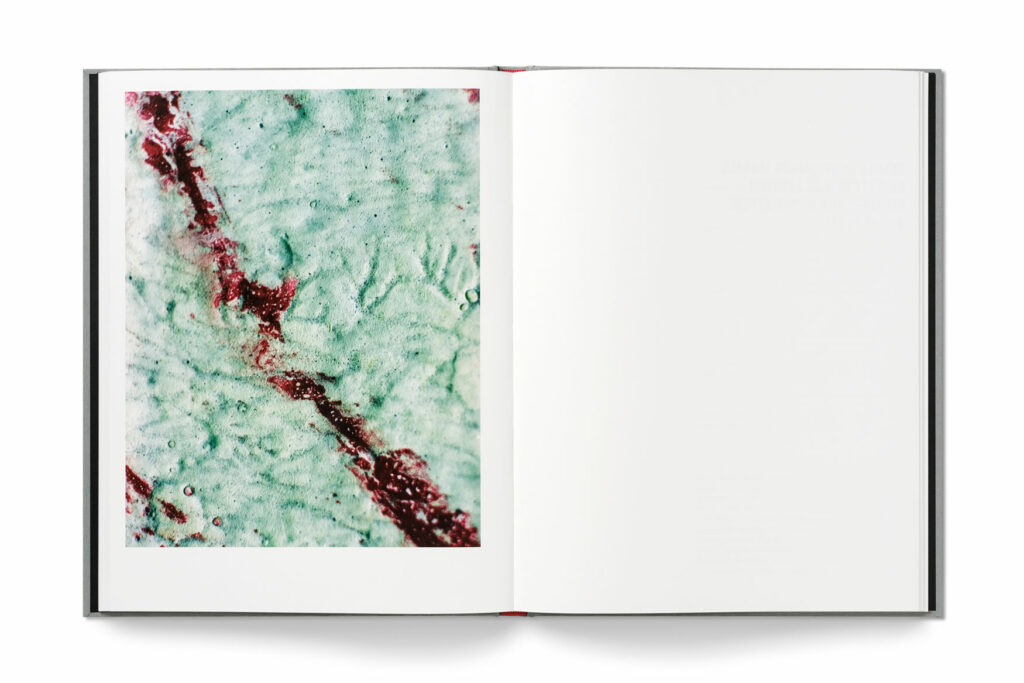

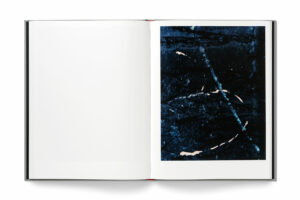

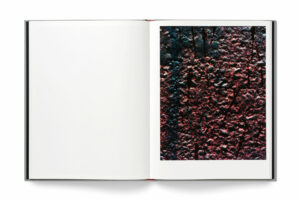

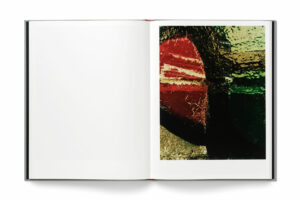

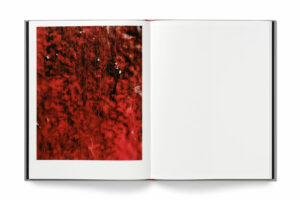

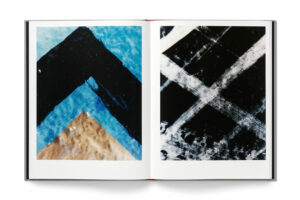

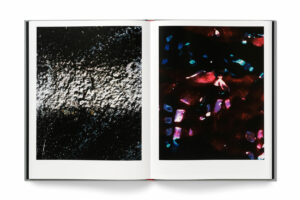

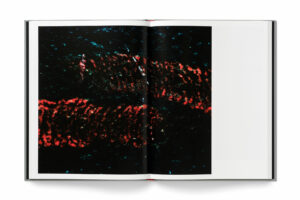

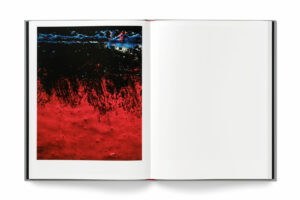

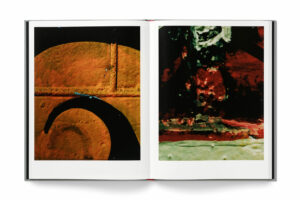

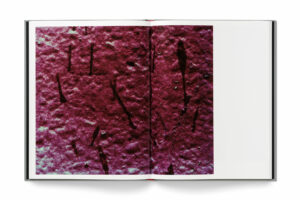

So, what might it mean to abstract these murals, to wrest them from their reality within the brick and mortar of the city? It purges the weight of context from the image, strips away the symbolism, and neutralises the rallying call imbedded within the murals. It also subverts the polarising ideology at the very heart of the murals. It is a radical act of decontextualisation rendering it impossible to situate the mural on one side of the sectarian divide or the other. That the Red Hand Commando is reduced to a swirl of red paint and an image of a Republican prisoner of war becomes flecks of black pigment is a wholesale rejection of a culture of binaries – Catholic/Protestant, Nationalist/Loyalist. The urge to decontextualise may also be born out of a weariness with this very act of categorisation that becomes almost involuntary for many people living in Northern Ireland. That process to identify friend or foe, insider or outsider – what Irish poet and playwright Seamus Heaney once described as:

…Manoeuvrings to find out name and school,

Subtle discrimination by addresses

With hardly an exception to the rule

That Norman, Ken and Sidney signalled Prod

And Seamus (call me Sean) was sure-fire Pape.

O land of password, handgrip, wink and nod,

Of open minds as open as a trap…[iii]

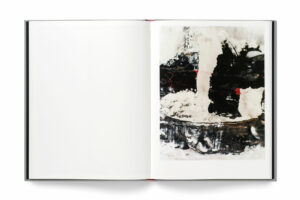

Details of Sectarian Murals also constitute a new kind of ‘Troubles image’. Throughout the conflict=the dominant image of Northern Ireland propagated through the press was reductive and polarised. Such images were frequently shot by foreign photojournalists working for the international media. Writing for Circa Magazine, Irish artist Belinda Loftus noted that this style of photography took a cue from American combat photographers of the post-1945 period. Loftus criticised its formulaic approachwhich often lapsed into tropes of “dramatic heroism and suffering in far-off lands.”[iv] The photograph’s status as evidence was also exercised during and after the conflict. Images shot by French photographer Gilles Peress, among others, were used as evidence in reports into the events of Bloody Sunday(both the Widgery Inquiry in 1972 and the Saville Report in 2010). Within this context, a turn towards abstraction can be viewed as a rejection of the often illusionary and oversimplified image of Northern Ireland disseminated through the media as well as an underlying scepticism in the photograph’s status as evidence. Instead, Details of Sectarian Murals broke new ground, offering a radical new language which embraces abstraction as a survival strategy.

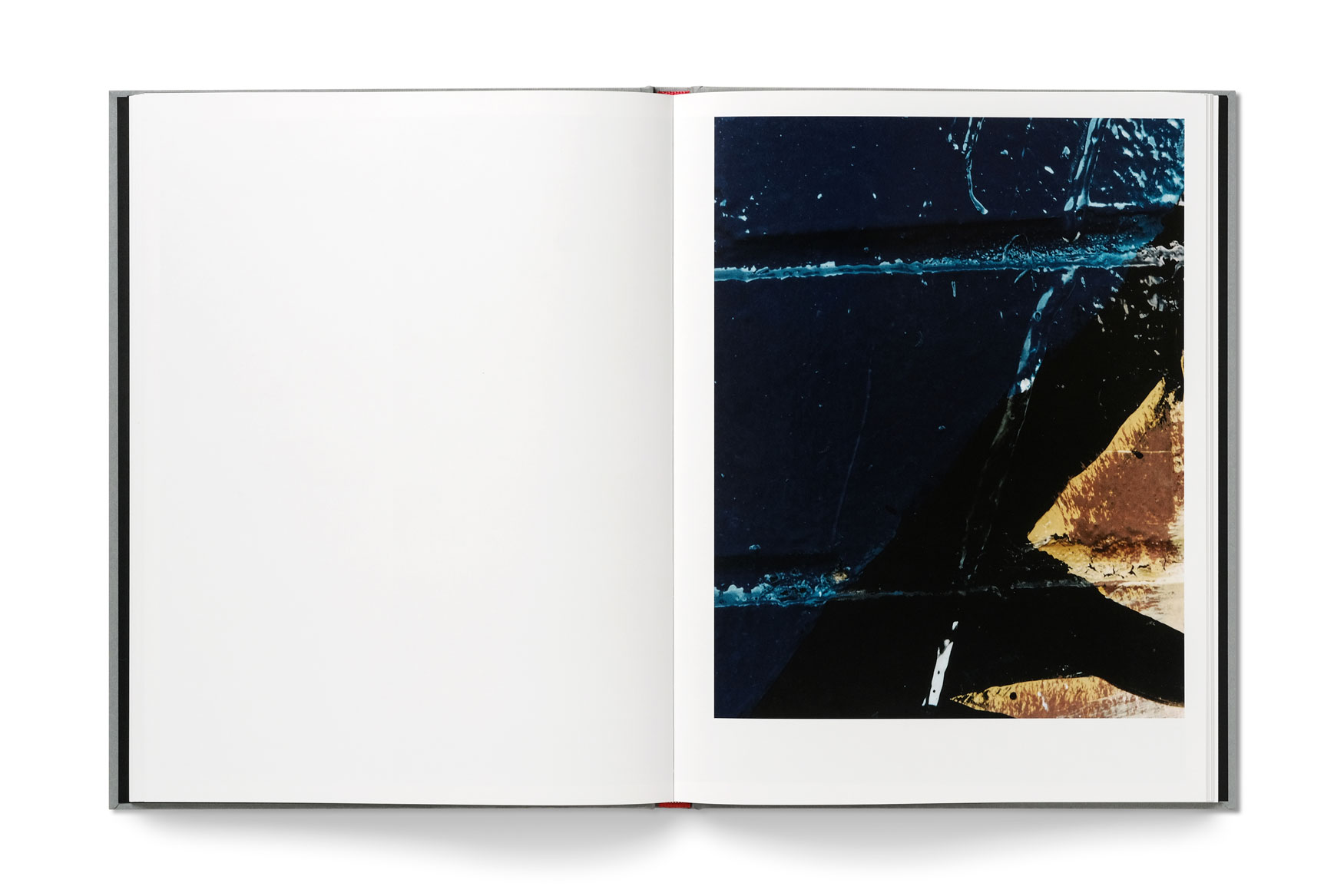

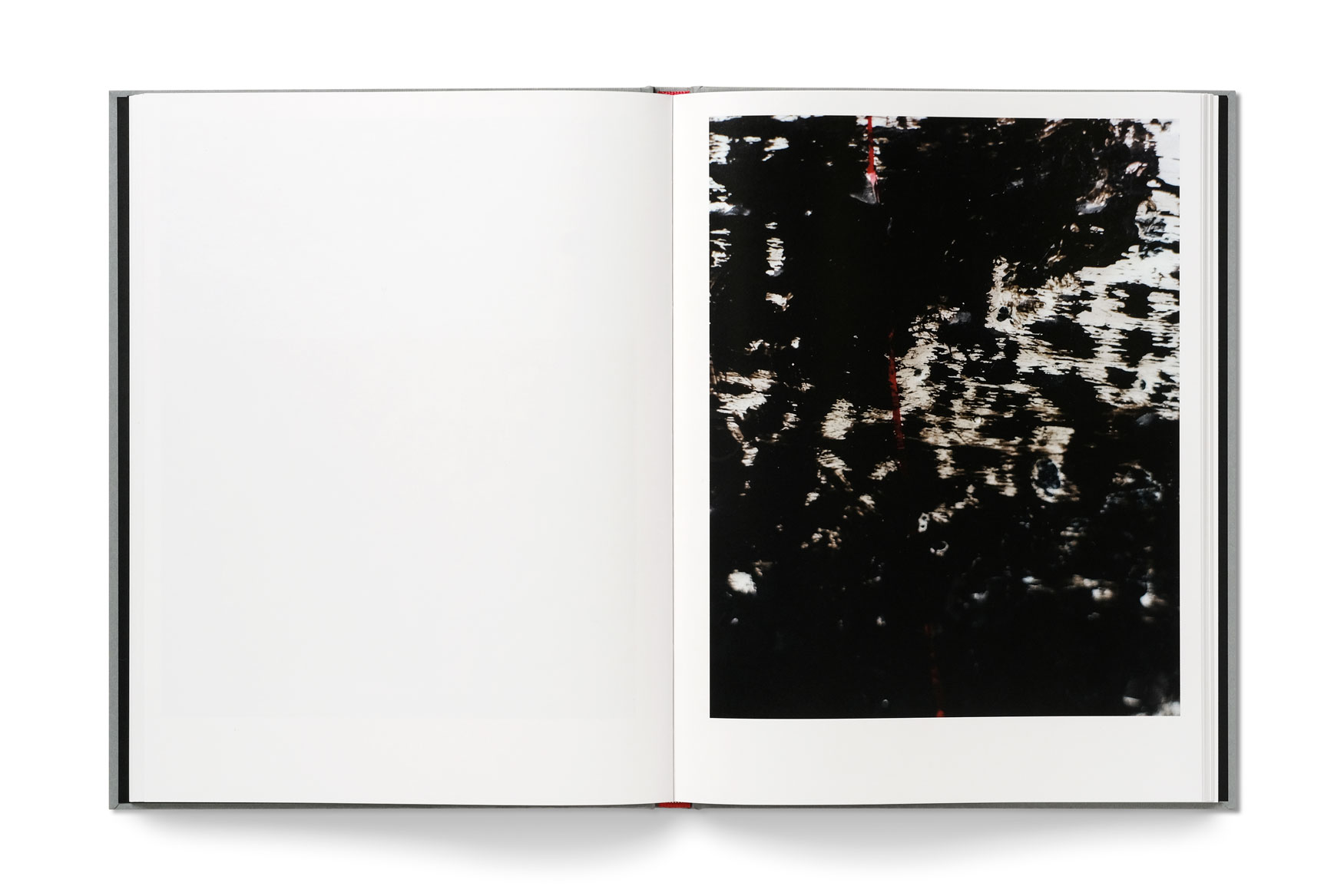

Spirit and Intention

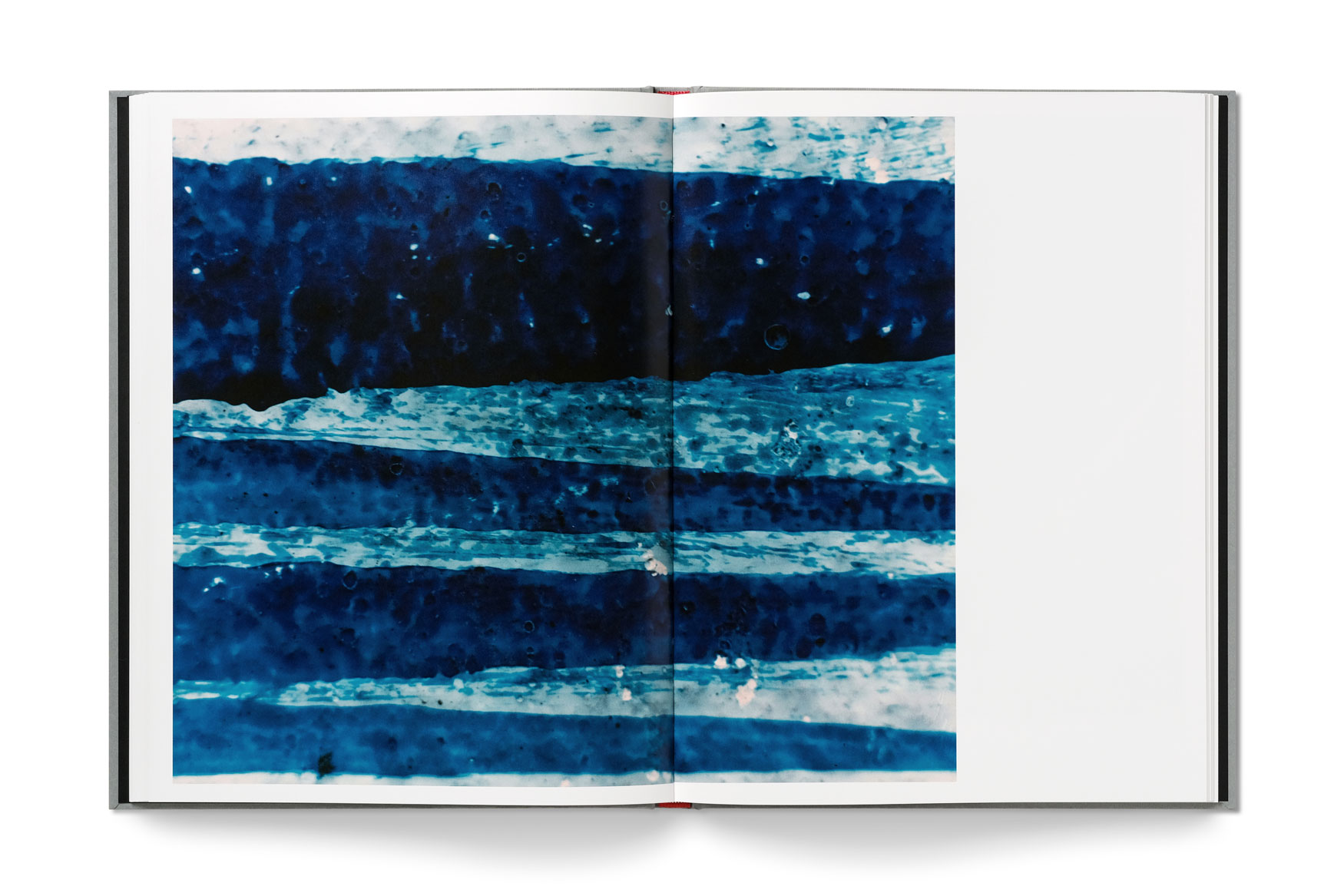

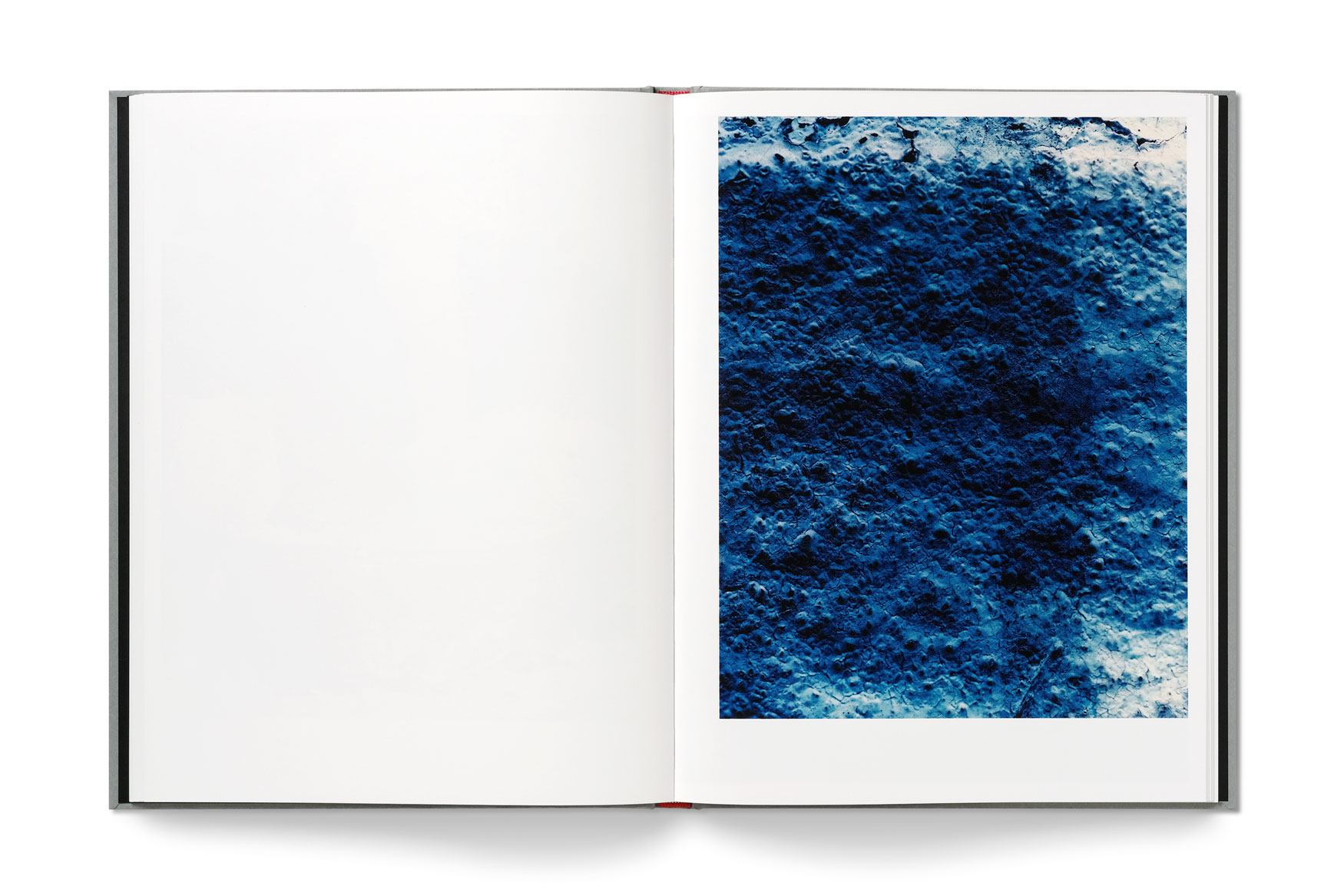

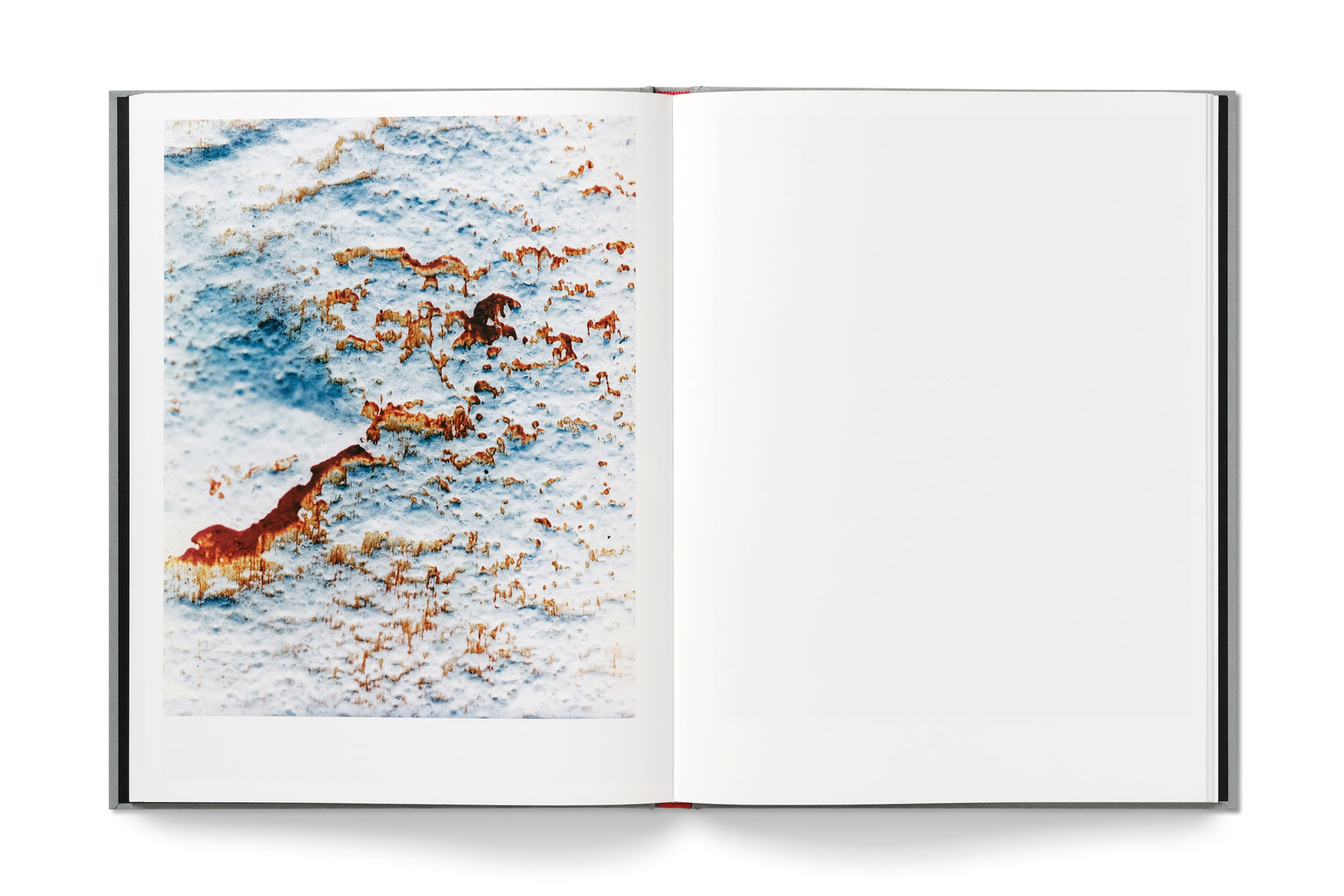

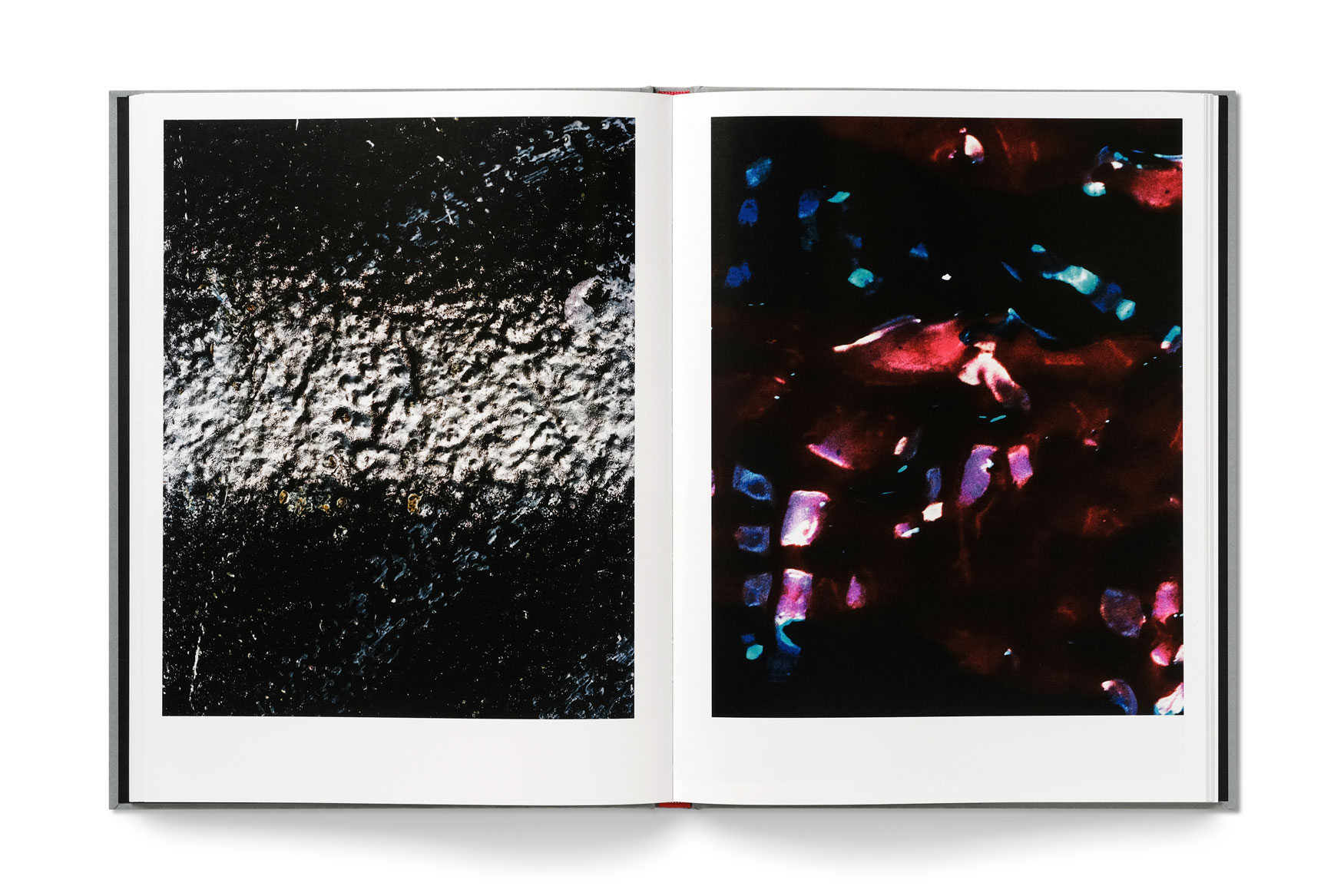

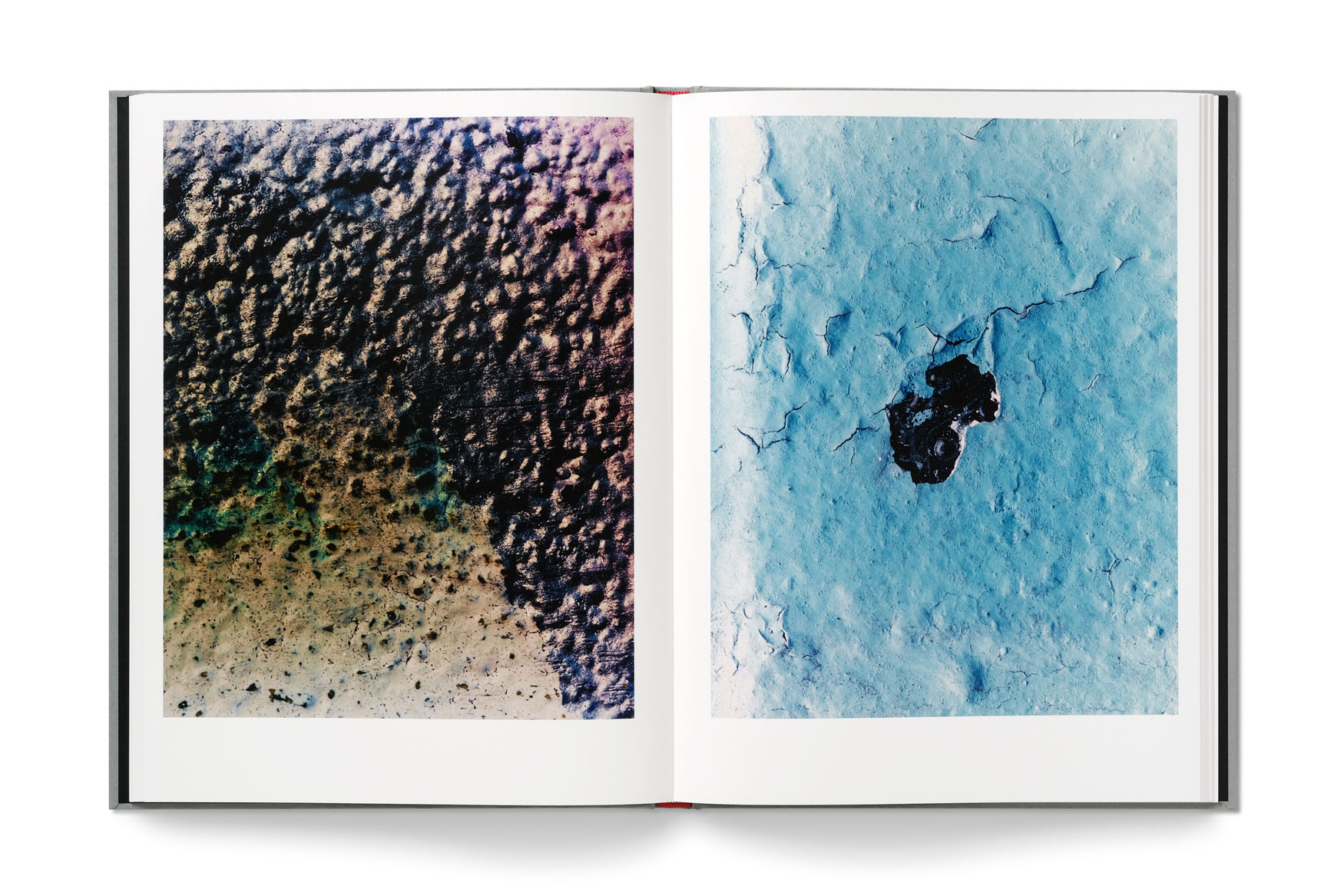

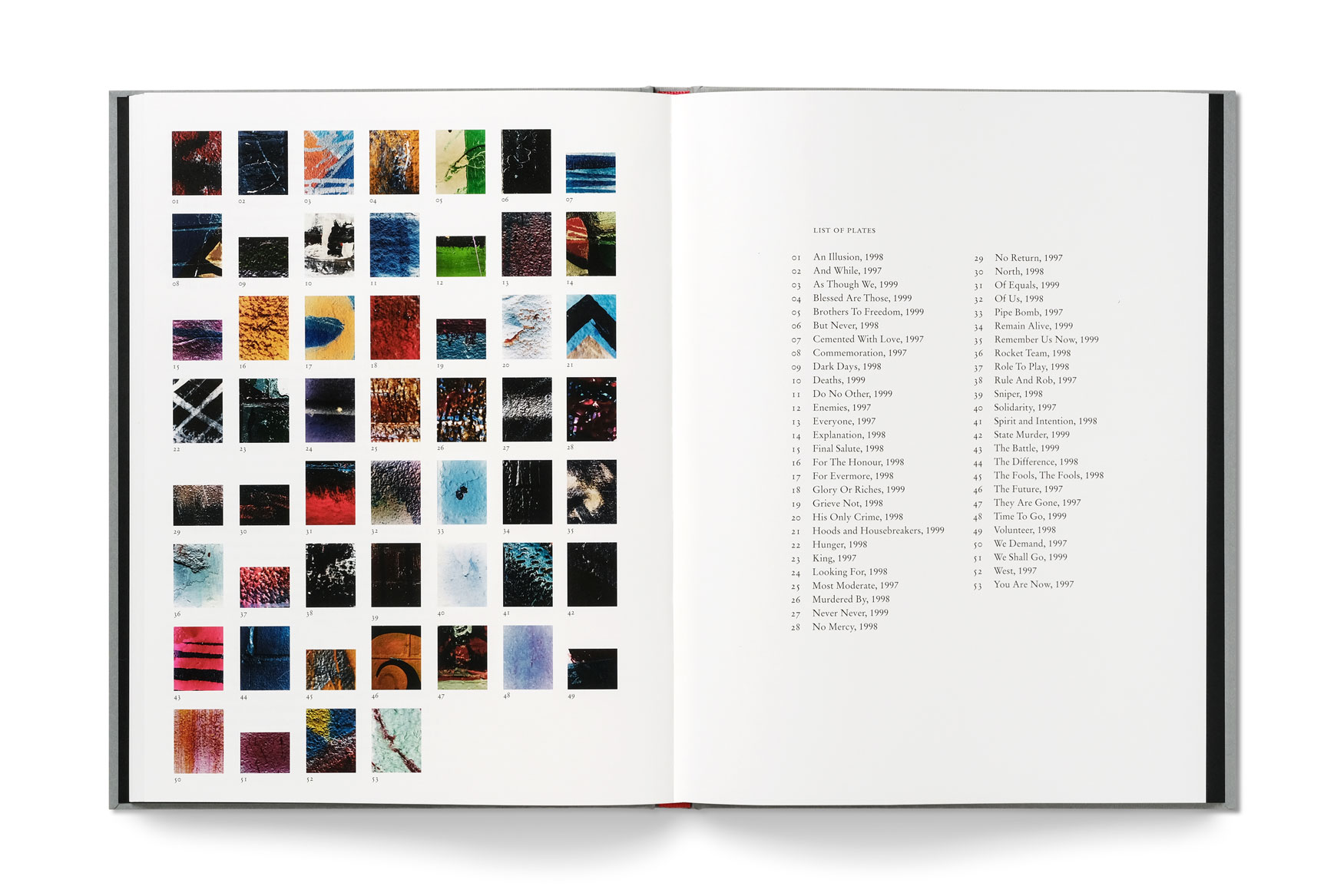

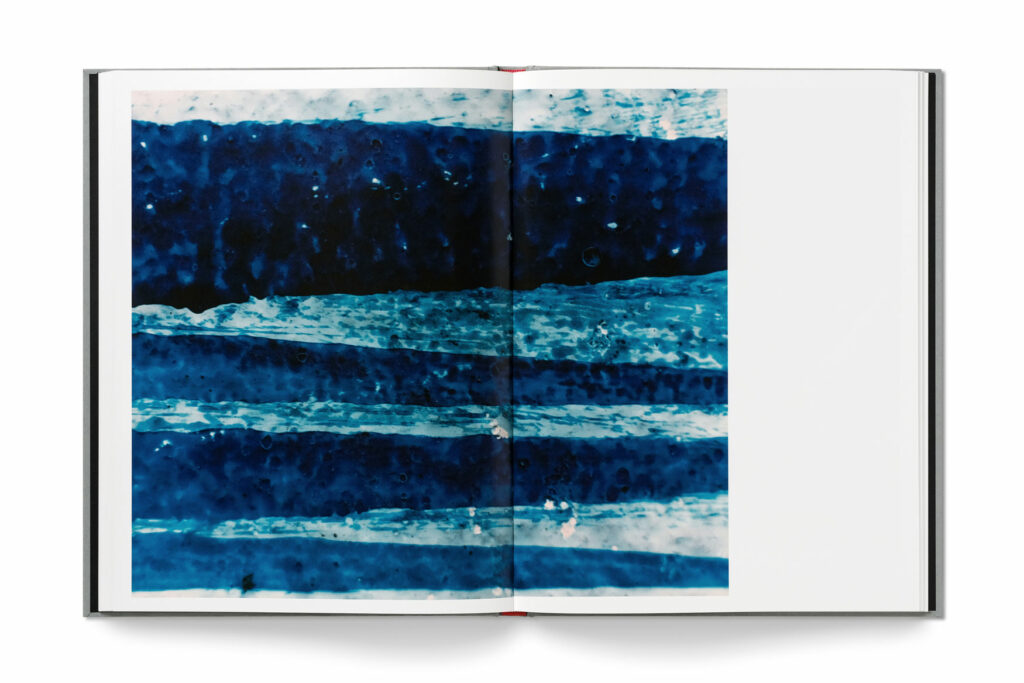

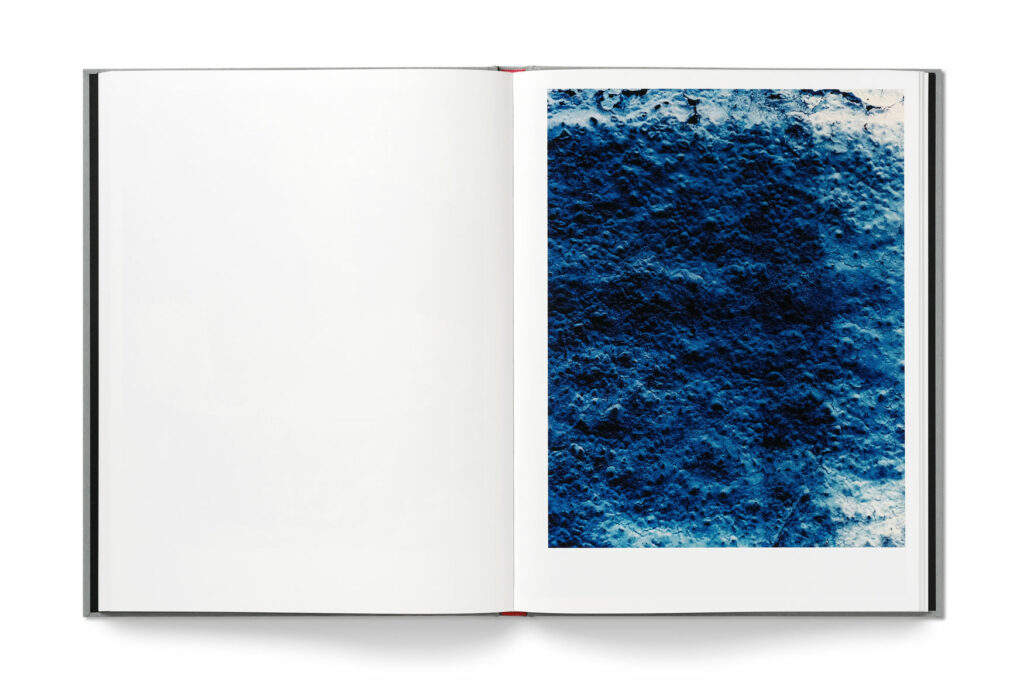

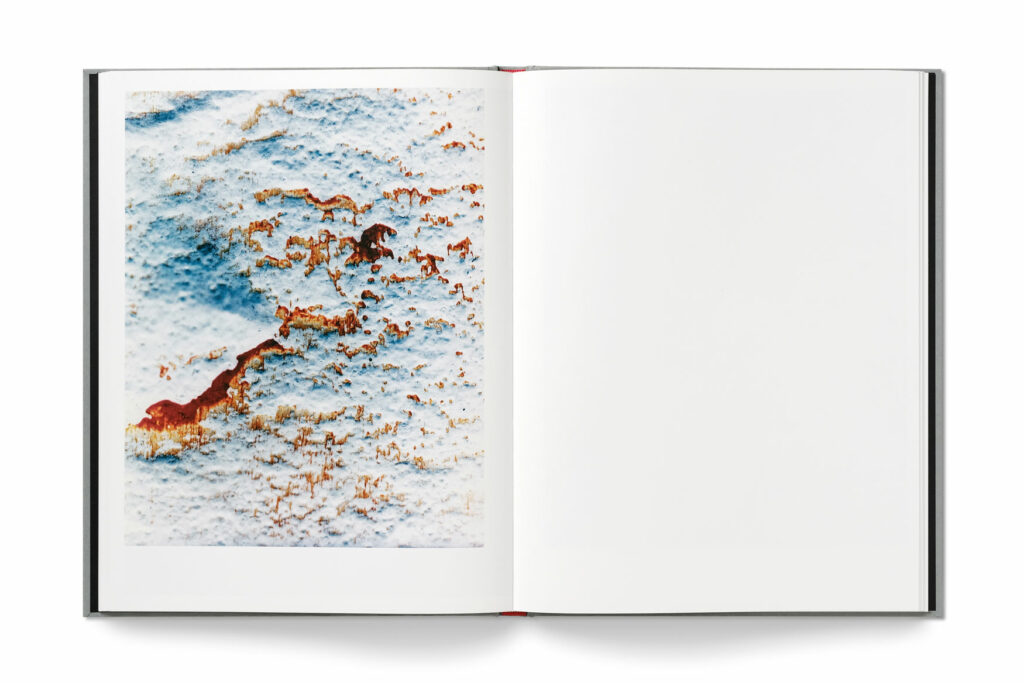

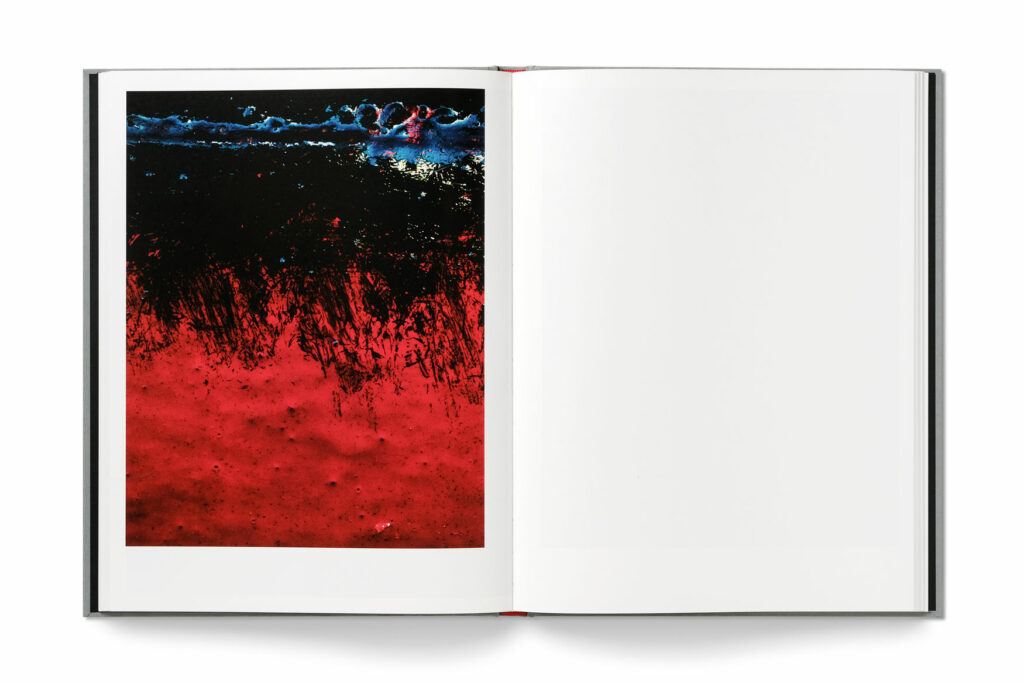

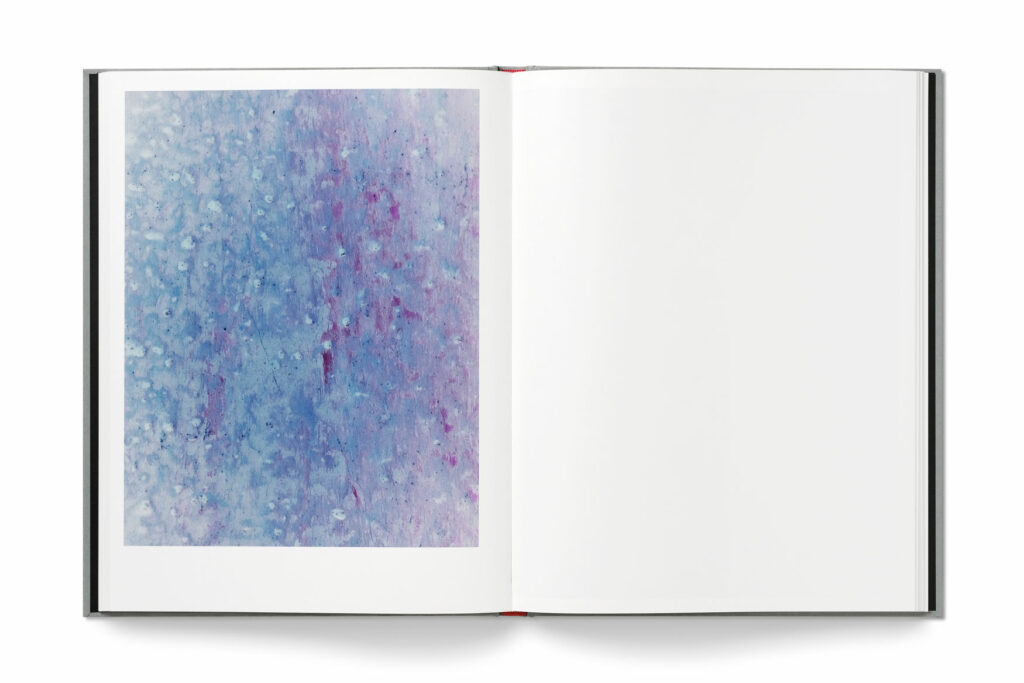

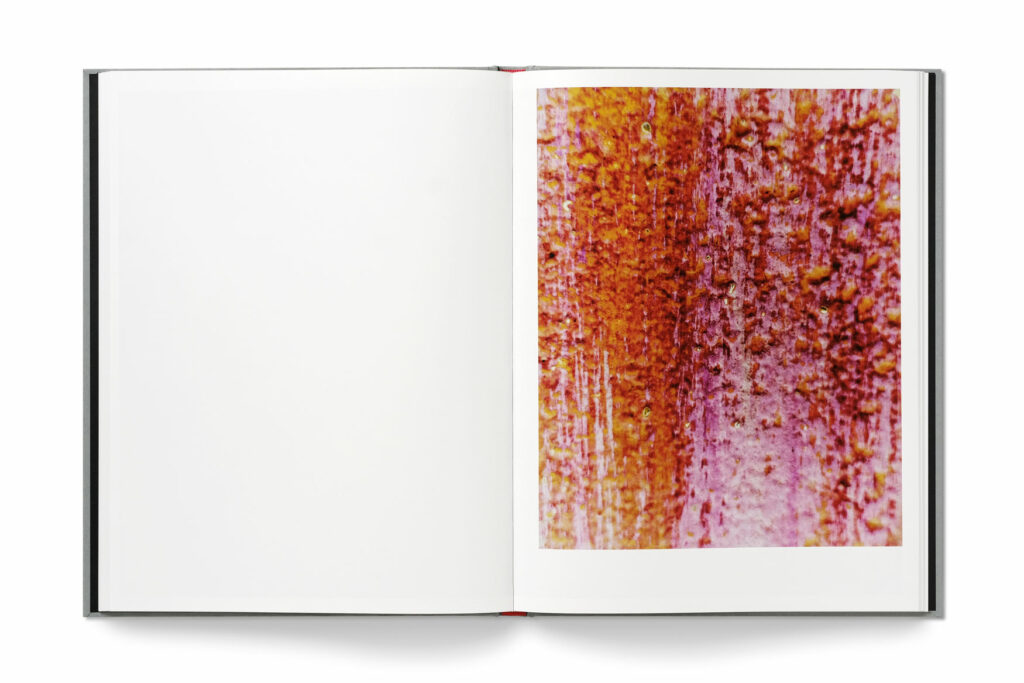

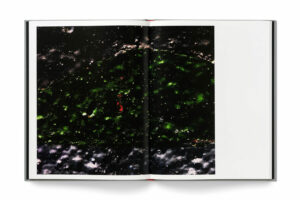

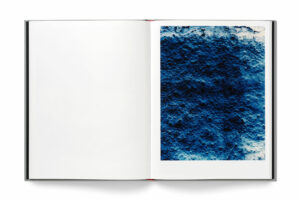

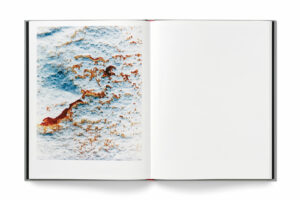

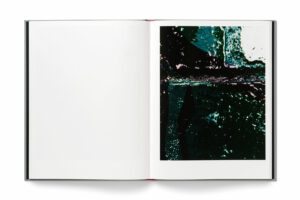

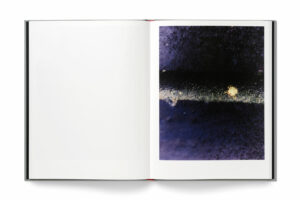

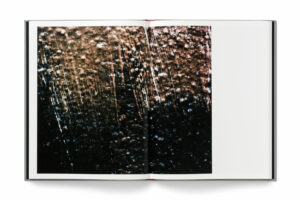

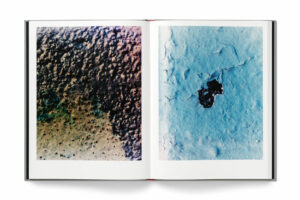

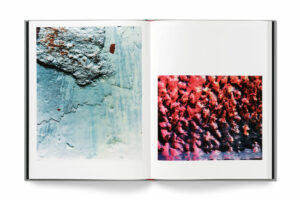

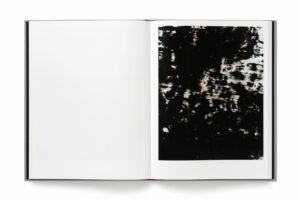

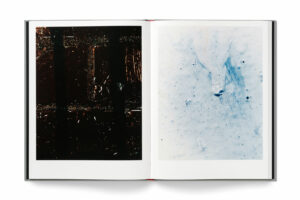

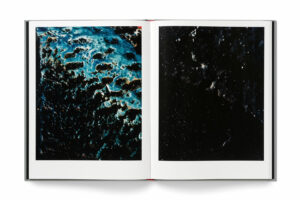

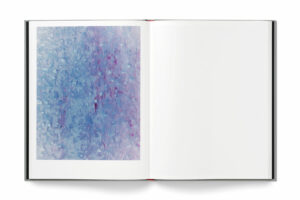

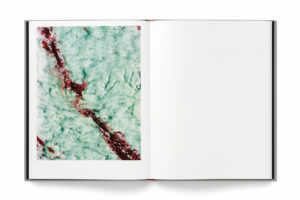

The survival strategy at play here is not solely defined by with what it rejects, but also by what it embraces. Details of Sectarian Murals delights in aspects of form in photography. The paint’s scratch, splatter, dot, and drip are revealed in tactile detail through a process of photographing at a 1cm distance from the murals. The images also invite a total immersion in a riot of colour – deep purples, piercing blues, and poppy reds. Here the words of Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, a reference point for the artist in this series, have resonance: “Colour directly influences the soul. Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another purposively, to cause vibrations in the soul.”[v]

Kandinsky’s words also remind us that abstraction in photography has often served as a spiritual pursuit, as well as a metaphor for the photographer’s emotions. If this is the case, Details of Sectarian Murals boil over with confusion, yearning, despair, and soul-searching. Yet there is also something uninhibited and wild with each image seeming to vibrate with sound. Rave music is an abiding influence for McConnell and indications of this are hidden within the work – the letter ‘E’ throws us a wink from one particular image. The sequence within this series feels as though it unfolds to De Niro by Disco Evangelists – a track powered by the era of ‘E’, pulsating with the euphoric promise of rave, but sampled with the sound of a threatening helicopter. Broken from the reverie, it is as if we could look up and see the British Military helicopter cutting through the Northern Irish sky overhead.

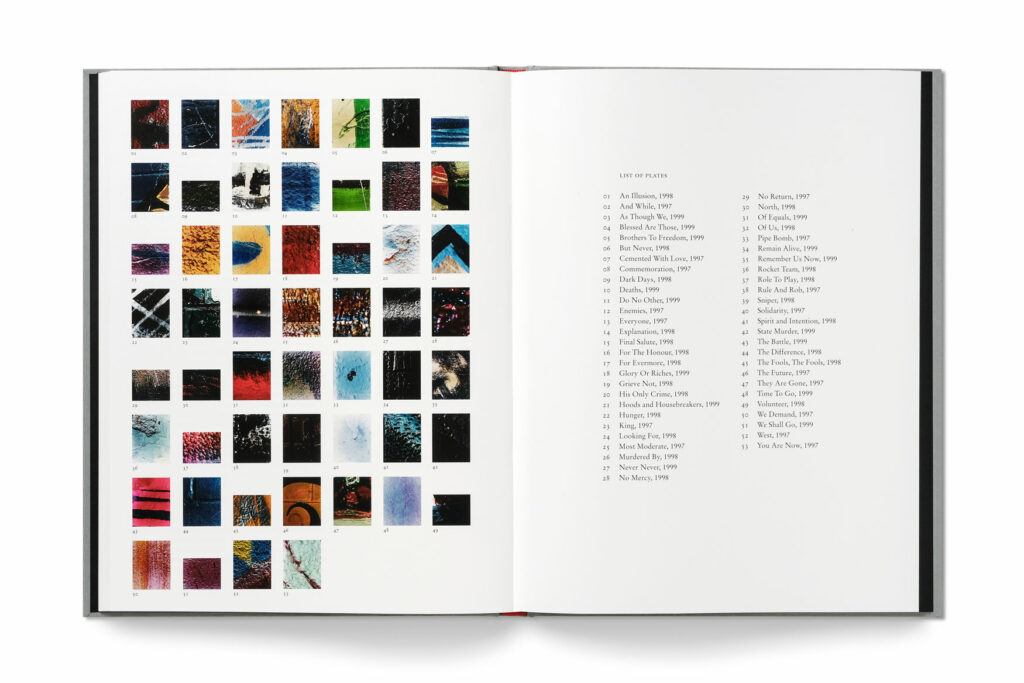

That sense of threat is also evoked by several of the image titles which are words and sentences extracted from phrases and slogans that appear in Northern Irish murals. They are clues towards a certain reading: ‘Hoods and Housebreakers’, ‘State Murder’, ‘Sniper’, ‘and ‘Grieve Not’. Other titles like ‘Dark Days’, ‘An Illusion’, ‘Spirit and Intention’ and ‘For Evermore’ remain open to multiple meanings. They are fragments that could be plucked, reshuffled, and repurposed so that the game of making new meaning from old murals might continue.

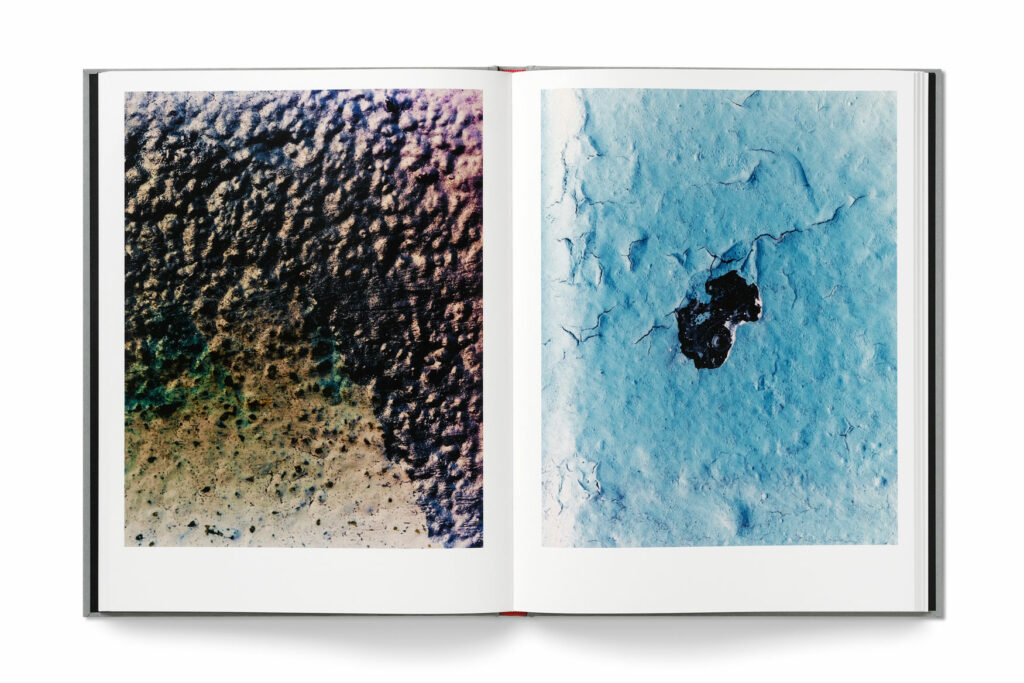

By honing in and extracting details from the urban landscape this series is situated within a trajectory of abstract photography. In the early 1940s, American photographer Aaron Siskind began making abstract photographs of weathered signs, graffiti, and peeling paint. More pertinent than the formal similarities that can be drawn between Siskind’s abstract images and McConnell’s is a degree of kinship in turning towards abstraction. Siskind began his career as a deeply political photographer but left aside the belief that photography was solely a medium at the service of social change. Instead, his goal became to make a photograph that was “an altogether new object, complete and self-contained, whose basic condition is order – (unlike the world of events and actions whose permanent condition is change and disorder)… ”[vi]

Do Details of Sectarian Murals also reach towards an altogether new object beyond a sense of disorder that attended Northern Irish civic society at the time? While the images appear spontaneous they are considered and insist on an internal order through the crop and frame.The series was shot at a time of heighted change between 1997 and 1999, these were the years just before and after the Good Friday Agreement was signed. Given this context speculation on what Details of Sectarian Murals might proffer in relation to hopes for the peace deal is tempting. Do they suggest that peace was all too abstract a concept? Or perhaps that for any peace deal to succeed the devil would be in the detail.

In 1994, when British photographer Paul Graham returned to Northern Ireland to capture an image that he felt represented the ceasefire he too turned towards abstraction. He photographed the skies across locations in Northern Ireland. Graham’s images were dark and ominous, revealing a haunting echo of the unionist slogan – ‘we will never forsake the blue skies of Ulster for the grey mist of an Irish republic.’ Perhaps then at watershed moments it is abstraction that is uniquely positioned to express unknowability, uncertainty and precarity – a pause or a gasp of air before a leap into the unknown.

For Evermore

In focusing on formal qualities of Details of Sectarian Murals it could be easy to forget that they are part of a complex social history and ever-changing physical reality. Murals in Northern Ireland are the subject of constant defacement, repainting, and erasure, like palimpsests one layer of history conceals another. Following the Good Friday Agreement, many sectarian murals have been painted over. In many ways it is a fitting metaphor for what some argue was a culture of amnesia and erasure on which The Good Friday Agreement was predicated.[vii] Northern Irish photographers Paul Seawright and John Duncan both documented whitewashed murals in their respective series Conflicting Account and We Were Here. Yet, as academic Justin Carville points out, visual seepages of the murals appear through the painted whitewash reminding us that “aesthetic cleansing is no panacea for the trauma of the past.”[viii]

So, what is the significance of revisiting Details of Sectarian Murals at this juncture in history as we mark twenty-five years since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement? The act could suggest that remembering the past and imagining a future are part of the same process. And what future might this series envisage? Details of Sectarian Murals are visual extracts from both sides of the divide. Brought together they mix traces of both identities, yet they are something entirely new at the same time. They might encourage us to ask what common ground we share beyond binaries. In 1991, the Irish critic John W. Foster noted that Northern Ireland was a community “yet to be imagined by the majority of its inhabitants.”[ix] Thirty-two years since Foster made this comment, we are poised to consider how this new community has been imagined, and how it will be re-imagined in years to come. Through abstraction Details of Sectarian Murals ultimately envisage something more universal, peaceful and serene – a utopic appeal that something might bind us beyond whether we are orange or green.

[i] Northern Ireland is the official name of the region. However there are several other names for the region which reflect differences in politicalviews. These include, but are not limited to: The North of Ireland, The Six Counties, The Province and Ulster.

[ii] Neil Jarman, “Painting Landscapes: the place of murals in the symbolic construction of urban space”, in Anthony Buckley (ed), Symbols in Northern Ireland, https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/bibdbs/murals/jarman.htm accessed on 1.5.23.

[iii] Seamus Heaney, North, Faber and Faber, 1975, unpaginated.

[iv] Belinda Loftus, “Photography Art and Politics How the English make pictures out of Northern Ireland’s Troubles”, Circa, 13, (1983), p.10.

[v] Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/22/92.pdf p19, accessed on 7.5.23.

[vi] A Siskind, “Statement”, in Aaron Siskind: Photographer, George Eastman House, 1965, p.24.

[vii] John Bew, “The lessons of Northern Ireland: collective amnesia and the Northern Ireland model of conflict resolution”. IDEAS reports, London School of Economics and Political Science, (2012), p.19.

[viii] Justin Carville, Photography and Ireland, exposures, 2011, p.159.

[ix] John Wilson Foster, Colonial Consequences: Essays in Irish Literature and Culture, Lilliput Press, 1991, p.281.