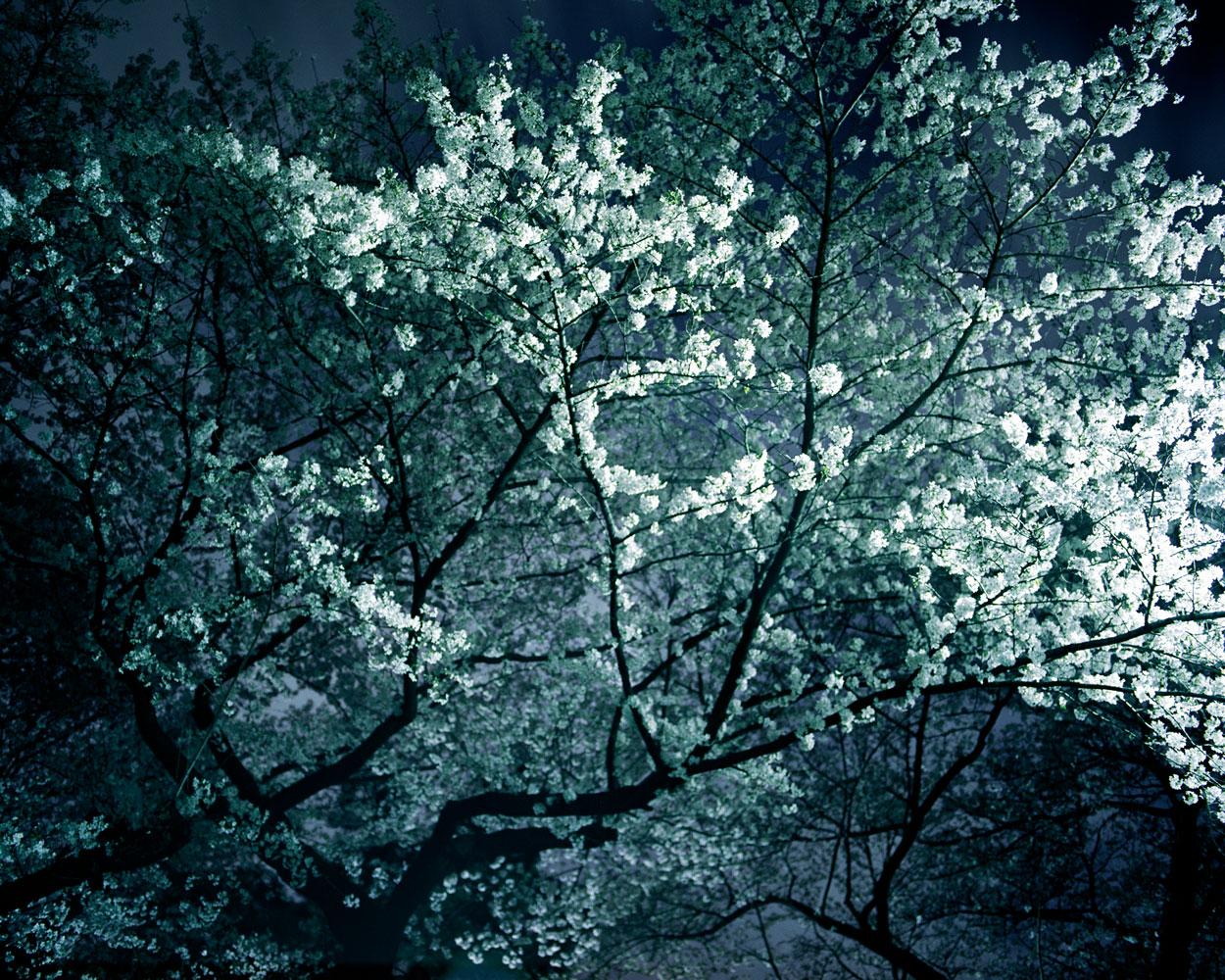

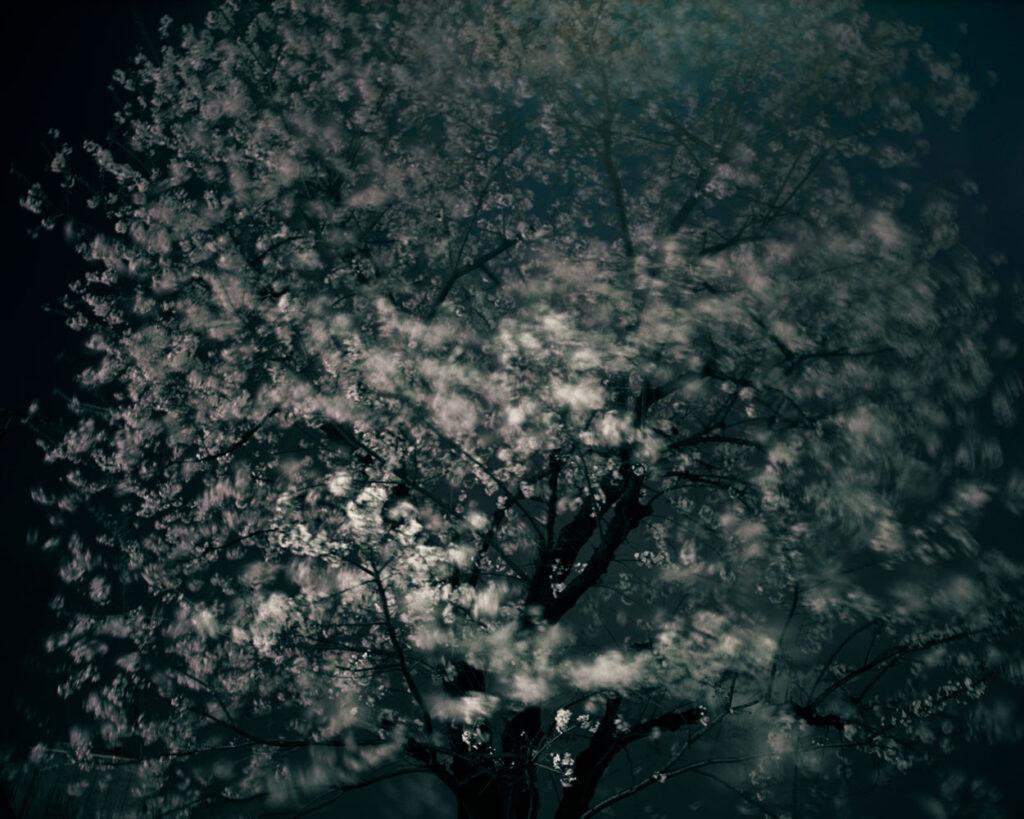

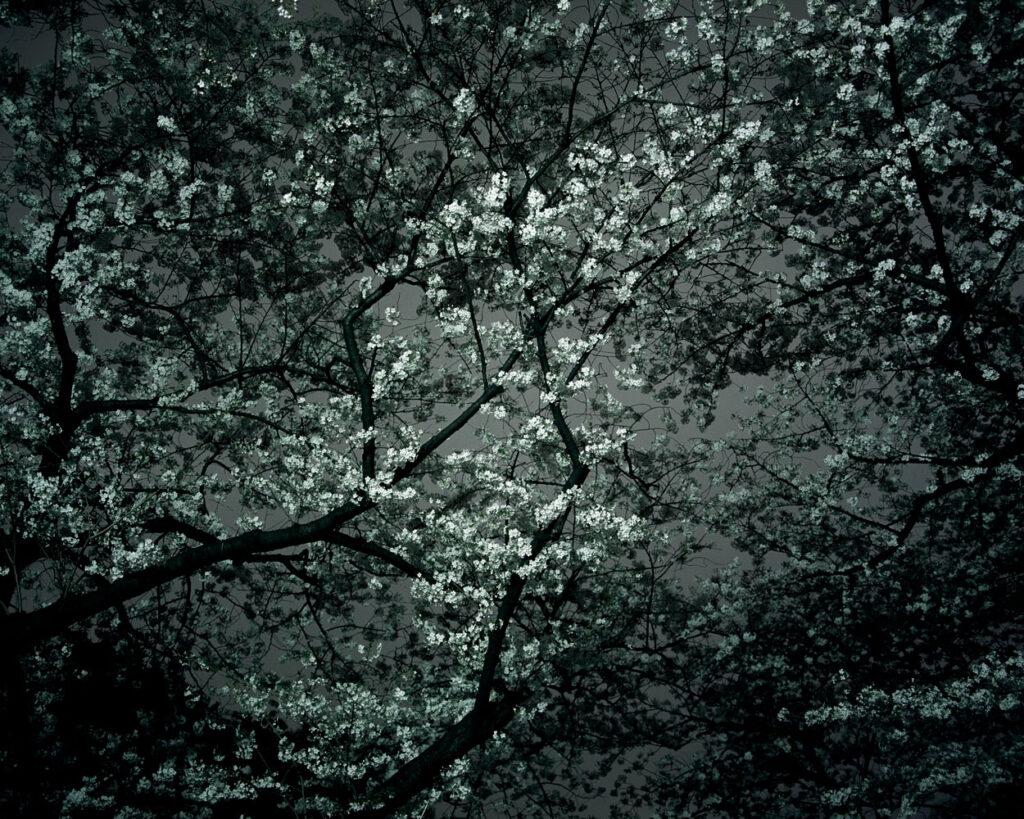

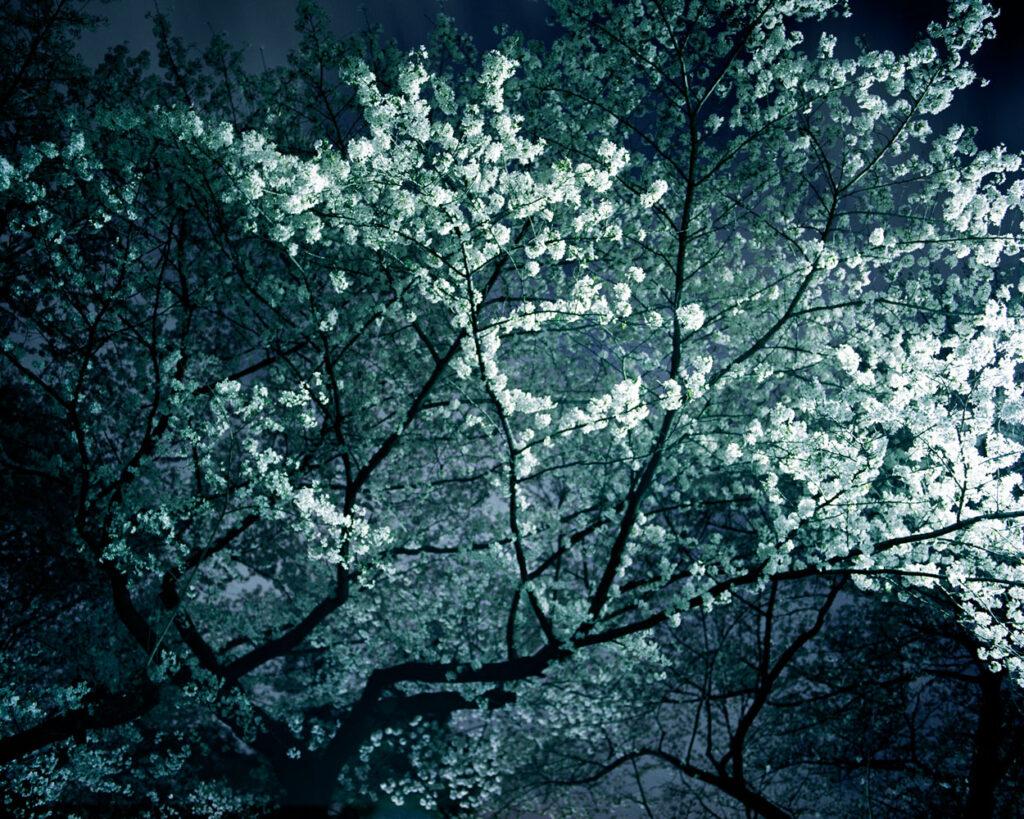

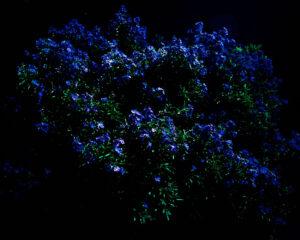

‘It’s Springtime and it’s dark and the city sleeps. Flowers emerge in strange places and he notices the flowers and then he photographs the flowers. Medium format. Tripod. Extended exposures, no flash. Tungsten-balanced film and available street lighting. And the camera sees the flowers quite differently from the eye. It offers up a glimpse into the optical unconscious. It shows us things that we never expected to find. Things that we never expected to see.

For McConnell the sublime and the monumental and the oh-so-fucking-sad-and-beautiful always reside in the people and the places and the things where you’d least expect to find them. In the Sectarian mural. In the Undertakers. In the Crackhouse. In the violated body. In the maligned and the marginalized. In the half-way-home. The oh-so-fucking-sad-and-beautiful. In people and places and things where you’d least expect to find it.

The Night Flowers are no different. They are a series of minor photographic revelations. Revelations in the sense that they reveal what the eye cannot see and what the night will not give up and what the city’s chaos and filth and concrete foreverness largely denies. They reveal a chance encounter with fragility, stillness and beauty. In the middle of a traffic island. In the shadow of a Corporate HQ. On a street in the ghetto. They offer transcendence, escapism and redemption. They reveal it where you’d least expect to find it. Colour in the dead of night.’

Simon Pooley

_____

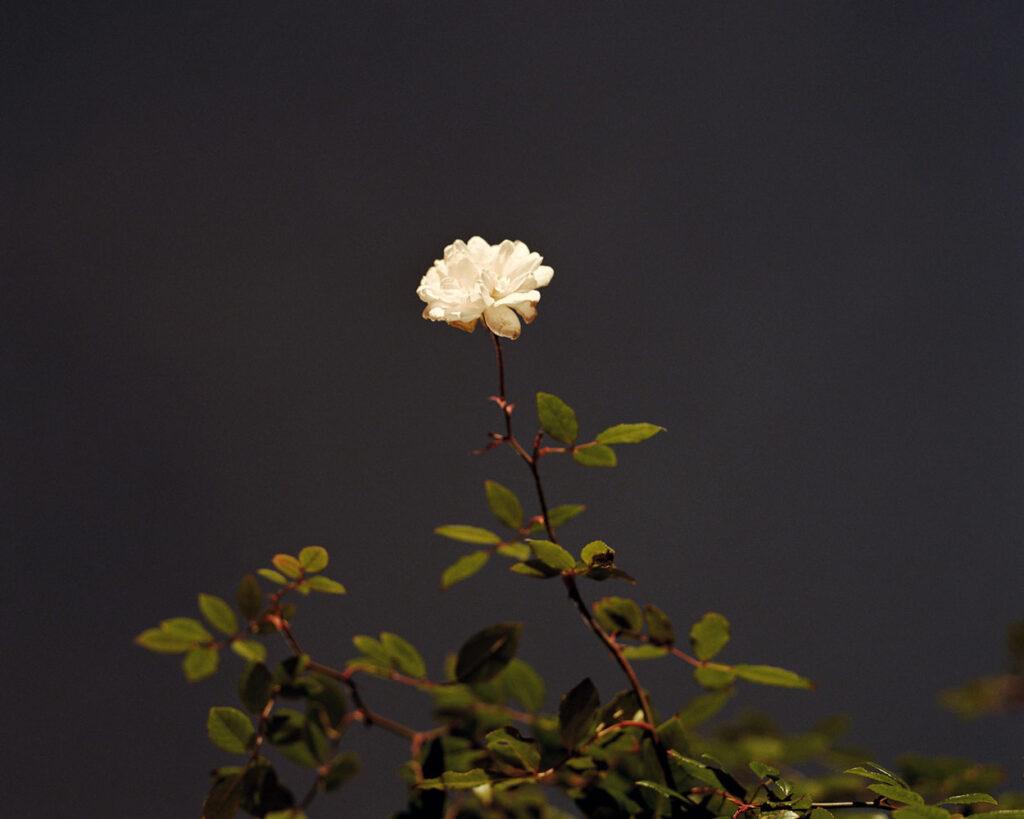

‘Flowers are, of course, deeply symbolic of renewal. Their beauty is bound up in the knowledge that it is momentary. Beauty pierces your heart because it is painful. It is about loss, transience, and wonder at its very existence.

Gareth McConnell’s photographs of his bed and flowers have to be understood with his other work in mind. The motivation and poignance behind the images in Meditations (2004–08), Night Flowers (2002–10), make little sense if you don’t know McConnell’s shocking and affective images in the series Anti-Social Behaviour Parts I & II (1995) — victims of paramilitary punishment beatings in his homeland of Northern Ireland, or IV drug users who were his friends and sometime community. This is true of beautiful things, isn’t it? Beauty is cloying and saccharine when it’s too easily granted.

McConnell shoots Night Flowers in ambient light and with a long exposure. He takes the pictures during nocturnal walks, another temporal experience out of the workaday. Similar to the beds, the flowers become still, central objects, isolated from their context (they are not hothouse but urban flowers, growing alongside commercial strips and housing estates). In some, a spray is classically composed against a background, blossoms burgeoning; in others the image is blurred, or the light intensely artificial, acidic. They are the dusty, forlorn cultivars grown on the streets of any city, but they are prize winners, too. McConnell asks with these pictures, can you find hope when and where it’s least expected?’

Alison Green

_____

‘…There is a another tap on the door. Which you now, slowly, pull open …knowing who is going to be there – a psychopath with fermenting breath and too much beer inside, someone who is both Republican and Loyalist, and who informs you that you are considered a burden on your community. It is you. THE PERSON AT THE DOOR IS YOU: YOU HAVE GRASSED YOURSELF, AND YOU ARE GOING TO BEAT YOURSELF UP. Holy God – not only are you the wrong religion, politics or faction, or a druggie instead of an alkie (or perhaps a figurative painter, whereas you should be a conceptually based visual artist, working in photography, or vice versa), but your trousers/ cardigan/ skirt are indeed quite, quite wrong. You are deeply uncool, AND YOU ARE GOING TO BEAT YOURSELF UP …

Thus insulted, your low self-esteem or helplessness requires you to bow to the inexorable righteousness of a profoundly negative auto-destruction, which means there is no exit out back – no lightly jumping over the garden wall as is done in films. Silhouetted in the murderous sodium streetlight you stand, the two yourselfs, each looking at the other, in an ancient complicity of divided torment. Into the rain and cold you go – maybe observing out of the corner of your eye something incongruously inappropriate to your situation. Something like Night Flowers, (2002) whose strange beauty causes you to wince.

On you go, each of the two of you, to a place where you will inflict on yourself crude agonies of pain, of such miserable effectiveness, that you may be permanently disfigured, mentally and physically; suffering a trauma so severe that you may – blessedly – lose consciousness, or worse: perhaps lapse into coma, or bleed to death …motherless, fatherless, alone.’

Neal Brown