Carrickfergus. Susan Mckay. Source 28 Autumn 2001

They’re selling plastic swords outside Carrickfergus castle. Up on the parapets, a redcoat soldier in a black tricorne hat aims his musket into the crowd below. On the grass, young soldiers in khaki from the Royal Irish Regiment are lifting little boys up into an armoured assault brigade vehicle. The children reach up on tip toe to try out the big guns on their swivels. ‘That’s a real soldier, son. See his gun?’ says a young man to his boy.

A young woman soldier sprawls against a wall, legs apart in her fatigues, telling a story to a muscular young man in civvies. He has a hard face. She hoists at her breasts, part of the story. He draws on his cigarette, rocks a little on his heels. The assault vehicle is strewn with camouflage foliage.

There is a pall of burger and chip smoke over Carrickfergus harbour. Three vans have parked between the squat castle wall and the supermarket car park, generators humming. Men in kilts with mirrored shades pocket their change, taking their first big bite as they turn away. Wedding guests. An ice cream man lies back in the driver’s seat of his van, smoking. He has a huge belly, like a made bed. There is drumming in the Castle. A luminous sign says this is a Medieval Fayre.

I ring Gareth McConnell at his parents house. ‘I’m at the Castle,’ I say. Whereabouts?’ he asks. ‘There’s a statue’, I say. I am looking at it. It is of a short man with long hair and big boots, hands poised, ready to draw his sword. His stance is agitated, his expression exceedingly crabbit. ‘I’ll meet you at the statue, then’, says Gareth. ‘Who is it, by the way?’ I ask. ‘King Billy’, he says, laughing at my ignorance. ‘He landed at Carrick, you know.’

When he arrives, Gareth says the councillors of Carrick had been displeased by the statue. It was too small. They’d expected something grander. ‘Apparently, he was a small man,’ he says, defending the sculptor. ‘Did you see the anchor at the side of the Boat Club? It’s from the Clyde Valley.’ This was the ship from which Edward Carson’s unionists landed guns at nearby Larne in 1912, ready to arm the Ulster Volunteer Force for rebellion.

On the seafront, tall, grey concrete slabs commemorate the 1914 battle of the Somme, to which Carson sent his men, an act of loyalty which would, it was understood, be repaid. The plaque records what King George V said: ‘the men of Ulster have proved how nobly they fight and die.’ The pare wreaths of red poppies are for soldiers who died then, in the Second World War, and, right through to the present – Royal Ulster Constabulary policemen, Ulster Defence Regiment and RIR soldiers.

Carrick has always been a warlike town. The poet Louis MacNeice, whose father was the town’s Anglican rector, described how ‘a huge camp of soldiers/Grew from the ground in sight of our house’. The UVF hadn’t gone away. A Carrick man was one of the gang that carried out one of the first sectarian murders of the Troubles in 1966.

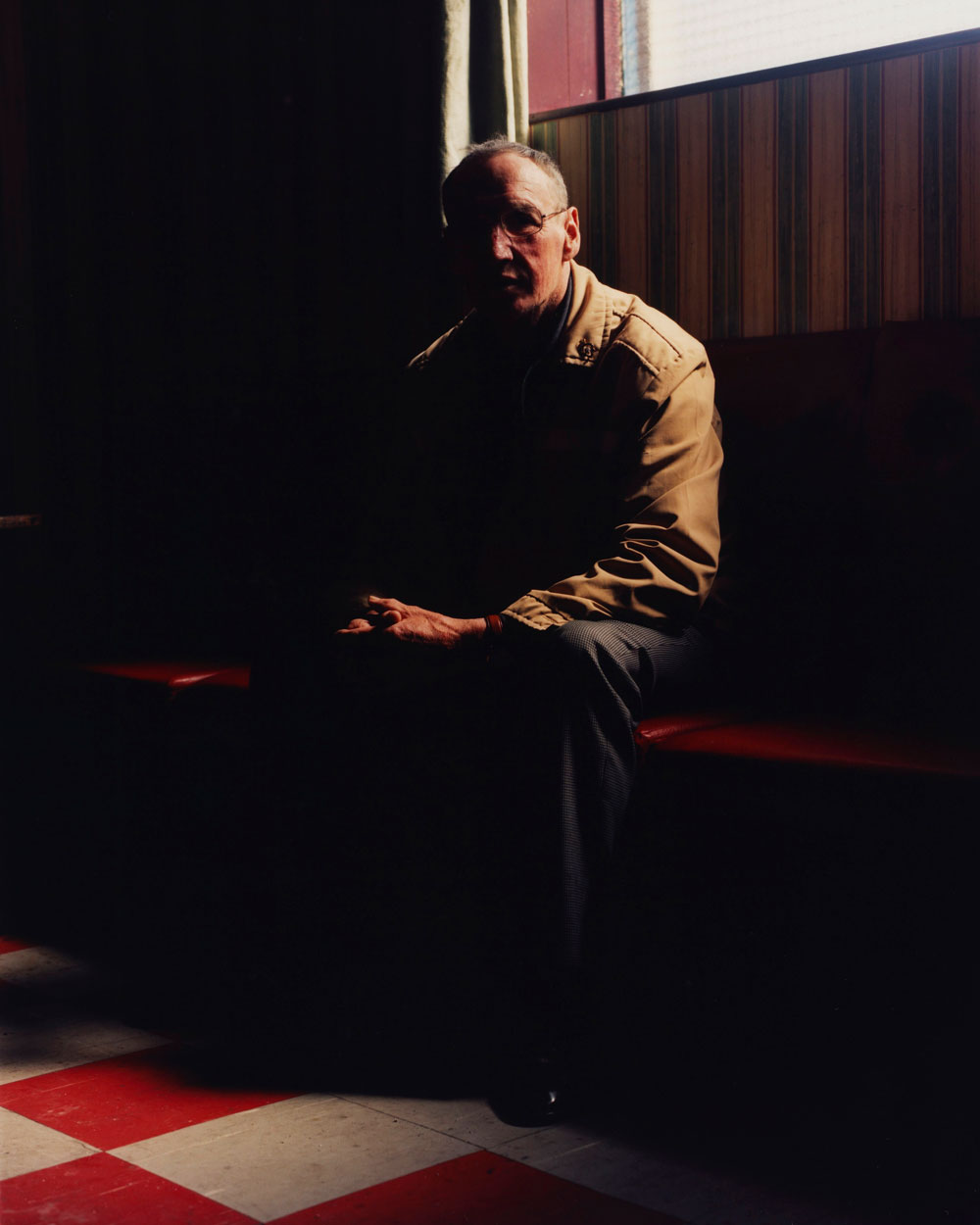

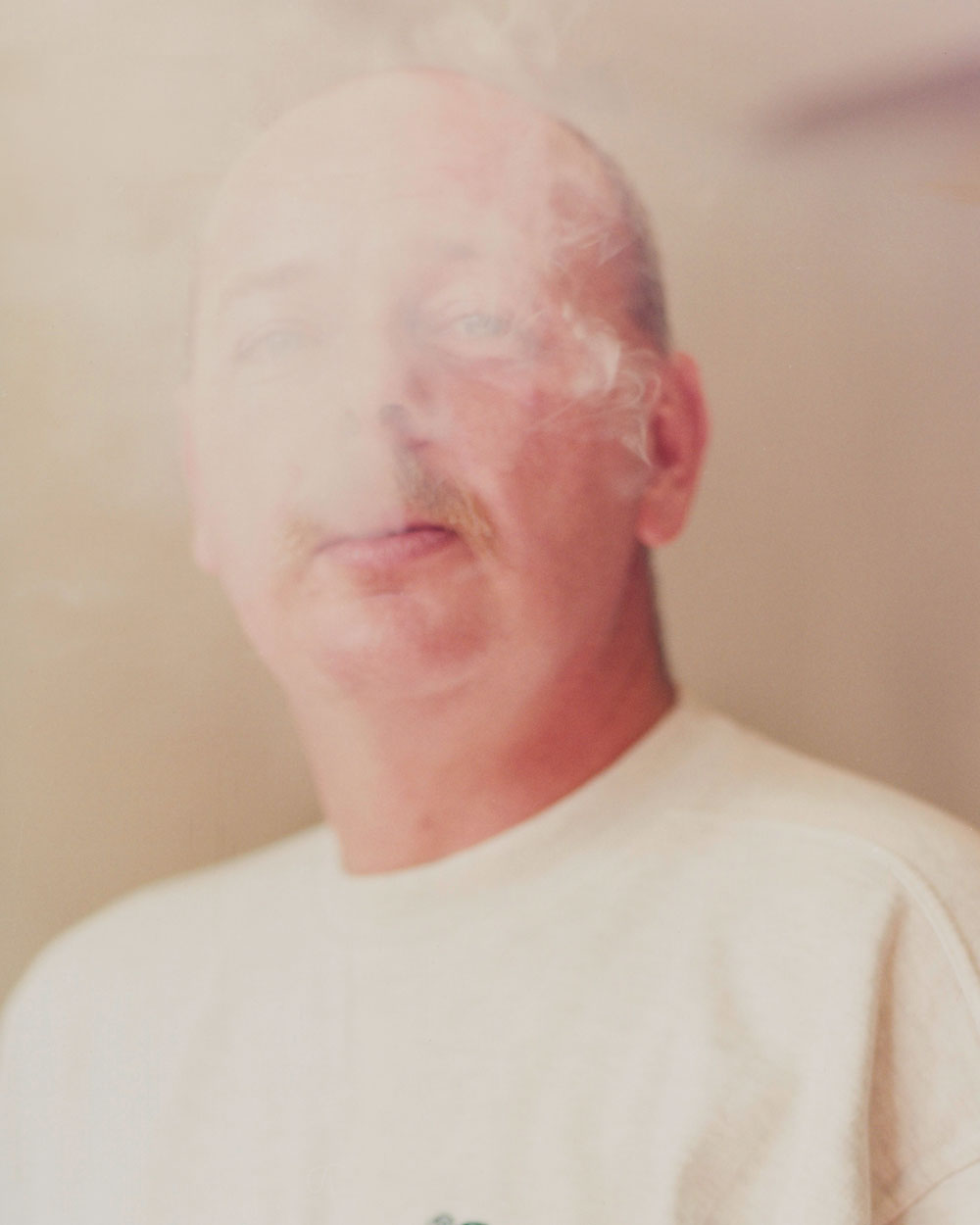

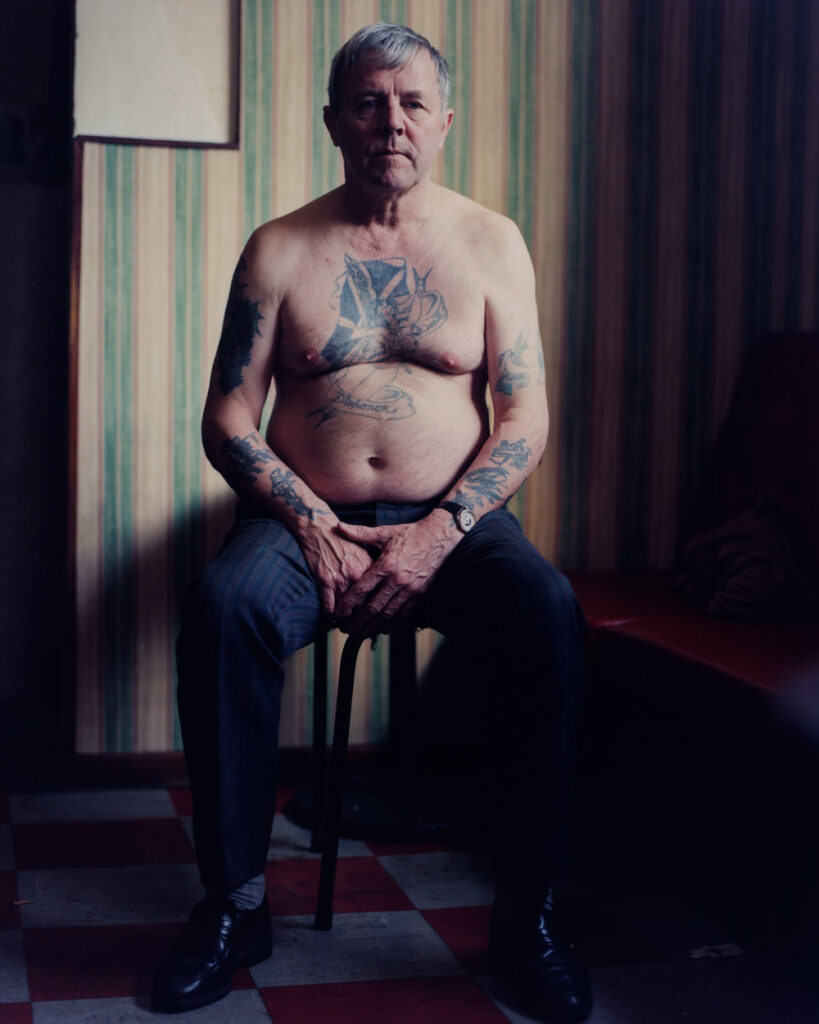

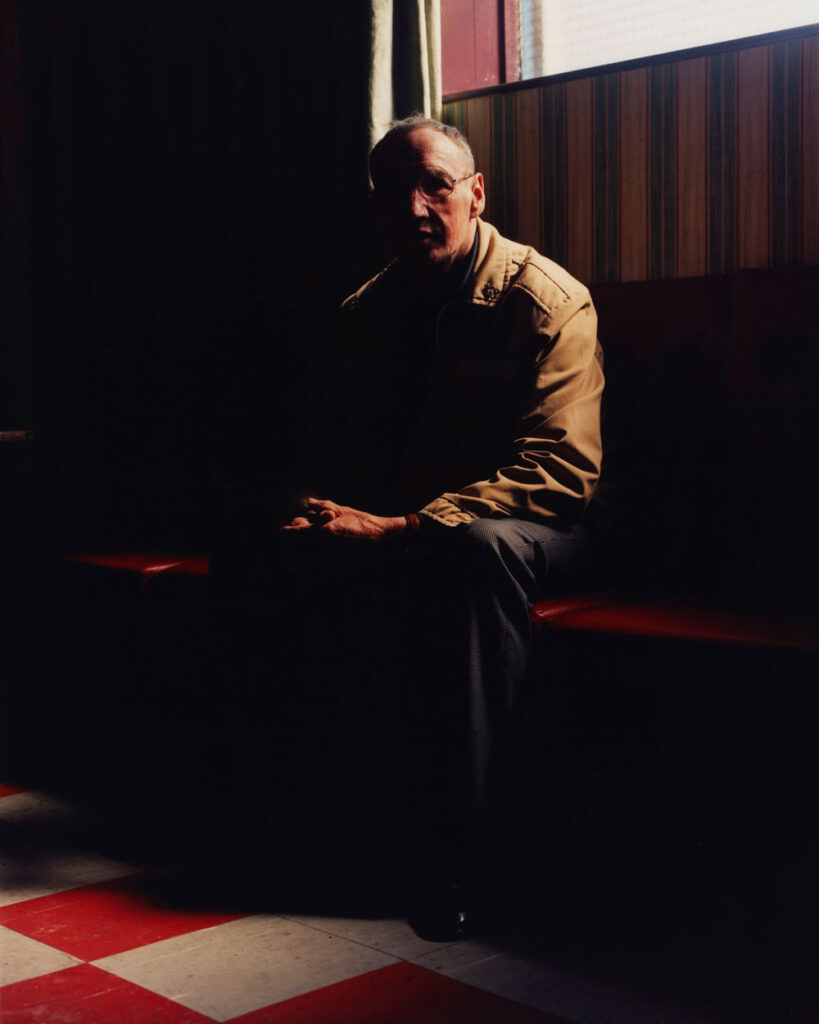

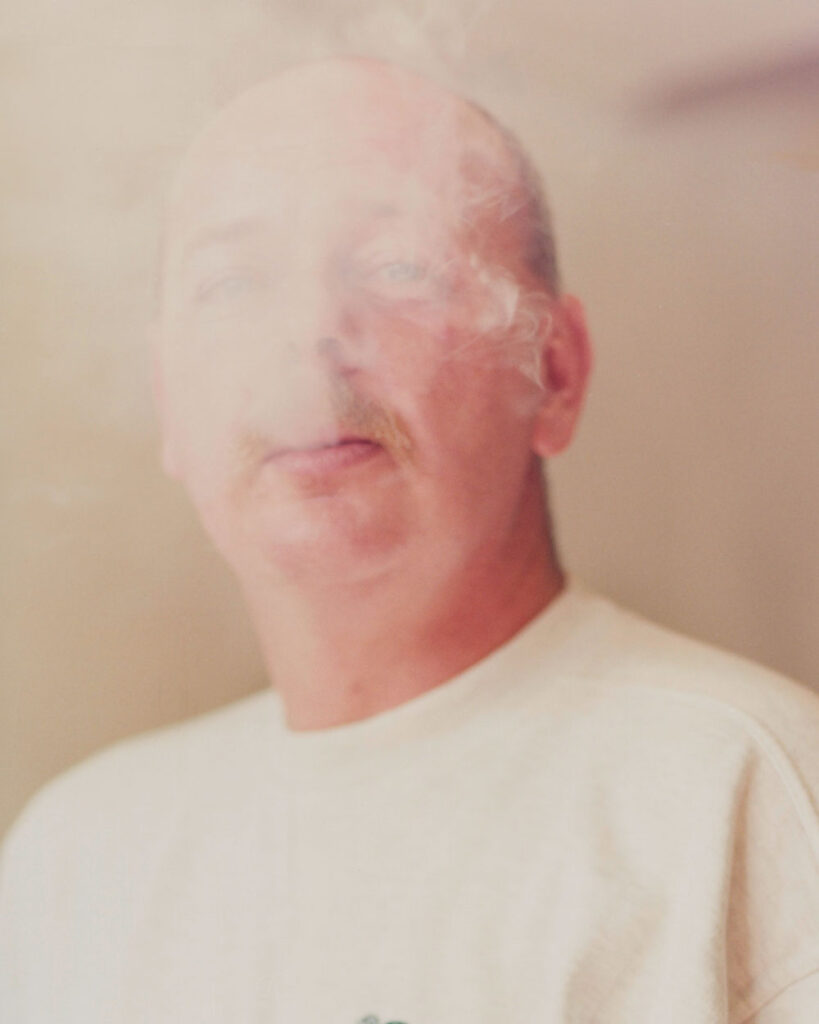

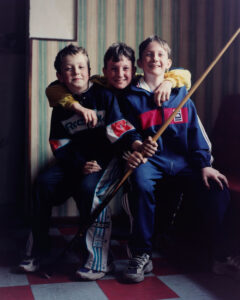

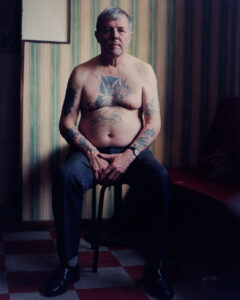

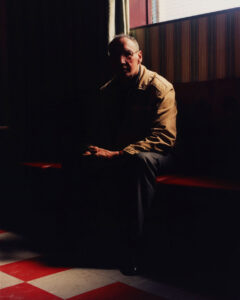

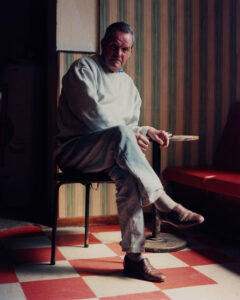

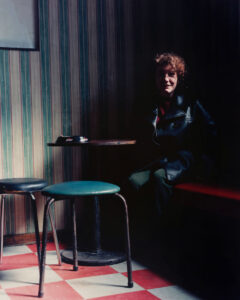

Some of those in Gareth’s photographs were soldiers in the paramilitary armies . ‘The three men in Loyalist Prisoners on Easter Parole were due to go back to prison in an hour or two’, he says. Loyalists are normally photographed in furious confrontation. Here, in this Carrick bar, they are among their own. A people who wear tattoos and gold. Calm. In repose. These are, as Gareth says, ‘dignified portraits’.

He took the pictures in 1999. The Good Friday Agreement had been signed. It was regarded as another betrayal in a history of betrayals. ‘The talk was along the lines of, ‘we’ve made an unconditional surrender to the IRA’, he says. ‘There was an air of resignation’. But there’s rage in those eyes, too.

Sometimes it seems in Northern Ireland, that the fiercer the town, the more flamboyant the hanging baskets of flowers. Carrick has lots of them, swinging in the North wind. A tourist board poster in a glass display board says, ‘I wish I was in Carrickfergus’, even though the song is about somewhere in Kilkenny.

A policeman told me once that there were Catholic girls in Carrick married to UVF men. As well as the sectarian murders there have been petrol bombs, pipe bombs, beatings and burning. The annual frenzy of Drumcree in 1999 say the town designated by the graffiti writers as a “Taig Free Zone’. The night after we met in Carrick, loyalists threw a pipe bomb into the home of a Catholic family in nearby Eden. The people in the huge houses on the coast road, with boats and cars and four wheel drives in the drive, seem oblivious.

Glenfield estate is above the above the town, with fine views over Belfast lough to Bangor, (‘under the peacock aura of a drowning moon’, in MacNeice’s poem). The estate is largely derelict now, the shuttered houses stained by paint bombs and petrol bombs. A local Ulster Defence Association big shot has made this his own. Catholics were driven out, rival paramilitaries, even a woman who had given her child a suspiciously Catholic name.

I’d written an article about the estate, and, soon afterwards heard on the news that shots had been fired there. I rang someone to find out what this was about. It turned out a man had called at the UDA leader’s house to see about his unpaid television licence. He had been seen off with shots in the air. ‘You could buy a house up here for next to nothing,’ says Gareth. On the gable wall of his Granny’s house, on a more settled estate, someone has painted up the words: ‘Thugs rule’.Jonathan Swift was a curate in Carrick. A town with its share of Yahoos.

We drive past many churches. The church of the Nazarene, the Elim Pentecostal, Free Presbyterian, First Presbyterian, Presbyterian, Church of Ireland, Baptist. ‘The Catholic church has just been rebuilt after it was burnt down’, says Gareth. The poet Derek Mahon wrote about his ‘credulous people’, of ‘bleak afflatus’, the temptation to ‘close one eye and be king’.

There are a lot of off licenses too. On our way back into the town centre, we pass under a bridge over which a banner has been draped: ‘Happy 40th BS’, it says. Gareth smiles. ‘I remember that guy knocked me out’, he says. ‘I was drunk and we were having an altercation. I said, “Listen, BS, if you are going to hit me, at least do me the honour of hitting me properly.” So he did’.

There was much drink and meaningless violence in his youth, he recalls. The secondary schools had to finish at separate times because of the amount of afternoon fighting on the street. ‘All Protestants’, he says. ‘What did you drink?’ I ask. ‘Thunderbird, QC sherry, Martini, Buckfast, Tennants, Bass Export… you name it’, he replies. He got into photography through his mother, who joined a class and came home with photos of Stiff Little Fingers. Then he went to art college in London.

Back at the statue, we sit on the wall and he shows me some more of his photos. This is a photographer drawn to the damage done. A man from a town with a history of ten centuries of wars which have never really ended.