Where Strangers Take You by the Hand

by Matthew Collin

Sometimes myths can be more powerful than reality. And sometimes ‘reality’ can appear to be little more than a patchwork of myths, held together by people’s desire to believe – a desire so strong that occasionally, in moments that cannot be predicted beforehand or fully explained afterwards, they are actually brought to life through the sheer force of will… or so it might seem as the warm Ibizan night opens up into the glow of dawn…

Ibiza is a place that draws people through the power of its myths. They will come again this year in their hundreds of thousands, seeking to live out their dreams of excess and epiphany, as they will next year and the year after that, to this little outcrop of rock in the Mediterranean Sea which has captured the imagination of travellers, hippies, ravers, musicians, writers, artists, sensation-seekers and freaks of many nations for decades.

“I was in harmony with the world for the first time…” The words of a spaced-out traveller in Barbet Schroeder’s 1967 film More – shot on Ibiza with a Pink Floyd soundtrack – will not sound unusual to those who have sought and found bliss here. But the contemporary myth of Ibiza has been formulated and embellished across decades, taking in centuries of influences that have washed up upon the shores of the Balearic island.

The first settlers came to Ibiza around the seventh century BC; the Phoenicians, who were looking for a staging post to service their maritime trading routes. They named the isle after Bes, their god of protection, safety and dance, and developed a flourishing cosmopolitan port. Over the centuries that followed, Carthaginians, Romans, Moors and Arabs also controlled the island, leaving behind their traces in its culture, until it finally came under Spanish rule in the thirteenth century.

Those seeking mystic precedents cite the naming of Ibiza after Bes as an indication that its spiritual magnetism meant that it was fated to become a place of revelries – and that the worshipping of another Phoenician deity, Tanit, the goddess of love and war, also foreshadowed its eventful destiny. But the contemporary Ibiza – or at least the clubbers’ paradise with its extravagant pleasuredromes and wild terrace debauches under the airplane flight paths, its sunset bliss-outs and clandestine outdoor parties – is also a product of the military dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain from his victory in the Civil War in 1939 until his death in 1975. Franco opened up seaside havens like Ibiza to mass tourism in an opportunistic hustle for foreign revenue to prop up his regime. In the late 1950s, the island only received a few thousand tourists each year, but by 2000, more than two million were arriving.

In the decades before tourist developments sprang up amid the rustic agricultural landscape of the ‘White Island’, the visitors were mainly bohemian adventurers and artistic freedom-seekers – people like the Berlin Dadaist Raoul Hausmann, who had fled Germany fearing repression in the 1930s after his art was branded ‘decadent’ by the Nazis, as well as other writers and painters from around Europe spooked by the rise of fascism and Stalinism.

The idea of Ibiza as a tolerant haven had been already been established when the island gave refuge to Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition, and was compounded when another wave of Jews escaping repression from mid-twentieth-century oppression also found safety here.

The 1950s brought beatniks seeking alternatives to San Francisco, Paris and Tangier as well as sunshine, laidback tolerance and cheap booze. Among them, according to Stephen Armstrong’s book The White Island, was a shady ex-US soldier known as Bad Jack Hand, who started to organise jazz gigs and beach parties – one of the many foreigners of dubious reputation and licentious appetites who have taken temporary refuge on the island. Bad Jack may have helped to develop Ibiza’s nightlife, but it seems that he was, as his name suggests, not such a nice chap, and he ended up in a Spanish prison serving time for murder.

With the 1960s came Americans dodging the Vietnam draft and also the beatniks’ spiritual descendants, the hippies, who were seeking to bask in the cosmic aura for which Ibiza had already become known; at the same time, their presence enhanced the image of an ‘isle of liberty’. Although Franco still ruled mainland Spain, life was believed to be more relaxed on Ibiza, attracting Spanish gays, who added another layer to the image: as a playground for sexual nonconformists.“Ibiza may be one of those centres where the representatives of the avant-garde of a new civilisation are experimenting with a new way of life. It is more primitive, more spiritual…” Barbet Schroeder once suggested, apparently touched by the utopian vibes (or possibly by the sun).

But while the impecunious hippie peluts (‘hairies’) enjoyed their nocturnal bongo parties, increasing numbers of wealthy jet-setters and showbiz celebrities were also starting to buy villas on the island; among them actors like Errol Flynn, Ursula Andress and Diana Rigg. Just like the hippies, they were taking the opportunity to live as they wanted in what was then a relatively wild rural environment where few people were watching what they got up to, and those who did notice, didn’t care too much.

Musicians followed the actors as Ibiza started to cloak itself in a sheen of glamour as well as countercultural chic. By the 1980s, pop stars were regular holiday guests: charismatic hedonists like Freddie Mercury and Grace Jones frolicked at the hotel run by another iconic Ibiza renegade, Australian Tony Pike, who claimed to have presided over a poolside oasis of post-prandial cocaine binges and intoxicated lust. Pike’s hotel was also used as the set for the video for Wham!’s chirpy cocktail-bar hit Club Tropicana, whose lyrics unintentionally seemed to encapsulate some of the island’s charms: “Let me take you to the place where membership’s a smiling face,” the song begins. “Where strangers take you by the hand and welcome you to wonderland…”

By the 1980s, with strongman Franco dead and a new Spain emerging, most of the elements that would define Ibiza’s image as a disco paradise were in place. Channelling the jet-set glamour along with the post-hippie afterglow, seminal clubs like Amnesia, Pacha and Ku had grown from ramshackle origins into lavish arcadian palaces. Amnesia’s DJ, Alfredo Fiorito, was another of the island’s many fugitives. He had sought shelter from the dictatorship in his homeland Argentina that was persecuting journalists and rock promoters like him, and at Amnesia he started to play the open-minded mix of Euro-dance, early house and funky alternative rock that would later be codified as ‘Balearic Beat’. Meanwhile another DJ, José Padilla, who was to define the sunset sound of San Antonio by playing the Art of Noise’s Moments in Love at the Café del Mar as the orange sphere eased gently down beneath the Mediterranean skyline, had arrived from mainland Spain seeking the liberties prohibited by Franco’s rule. Perhaps just as importantly, a colony of devotees of the millionaire guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (later known as Osho) was bringing in supplies of MDMA to use in its rituals. The little-known ‘love drug’ would soon percolate through to Ibiza’s dancefloors.

And then another turning point: the summer of 1987, when four working-class lads from South London arrived for a week’s holiday, as so many had before. But this quartet of relatively unknown British DJs was destined to complete the contemporary Ibiza myth and instigate a global dance-drug movement, although they could hardly have known it at the time. It started when these four unlikely history-makers, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker, took Ecstasy for the first time and then went off to hear Alfredo playing records at Amnesia.

As they danced into the Mediterranean dawn alongside glamorous girls and flash Spanish boys, wealthy dilettantes and flamboyant transvestites, designer-clad extroverts and tanned fiftysomething libertines, they realised they had discovered something special, as Oakenfold said much later: “We’d found the holy grail; we’d found this spirit, this music, this energy that changed our lives.” But what was more significant was how they succeeded in reappropriating their seemingly ephemeral experience, demonstrating again the British entrepreneurial flair for repackaging pop-cultural ideas. Desperate to keep the MDMA vibe alive, they decided to take their holiday back with them to dreary London and started clubs like Shoom, Spectrum, Future and The Trip – clubs that would launch the acid house movement, turn Ecstasy into a mass-market narcotic and transform Ibiza into Europe’s nightlife mecca.

Their attempt to export their idea of Ibiza to a tougher northern climate coincided serendipitously with Britain’s industrial decline under Margaret Thatcher’s government when economic decay left behind empty spaces that were perfect for reinvention as illicit dancefloors. The oceanic Ibiza feeling was reinterpreted, the music hardened up, and the experience was recharged with renegade thrills.

Britain’s scandal-hungry tabloid media helped by effectively promoting the scene with shocked reports of bizarrely-clad youths dancing in their thousands to weird electronic music at outlaw parties in open fields, disused factories and aircraft hangars, all under the influence of some mind-bending new narcotic. Three attempts by Conservative governments to legislate against raves – most notoriously with the 1994 Criminal Justice Act which proscribed (under certain circumstances) the playing of “repetitive beats” – scared off many of the party pirates and drove mass rave culture back into the clubs. But it continued to thrive, and would dominate the country’s nightlife for more than a decade, in turn inspiring yet more young Brits to seek out the Balearic motherlode.

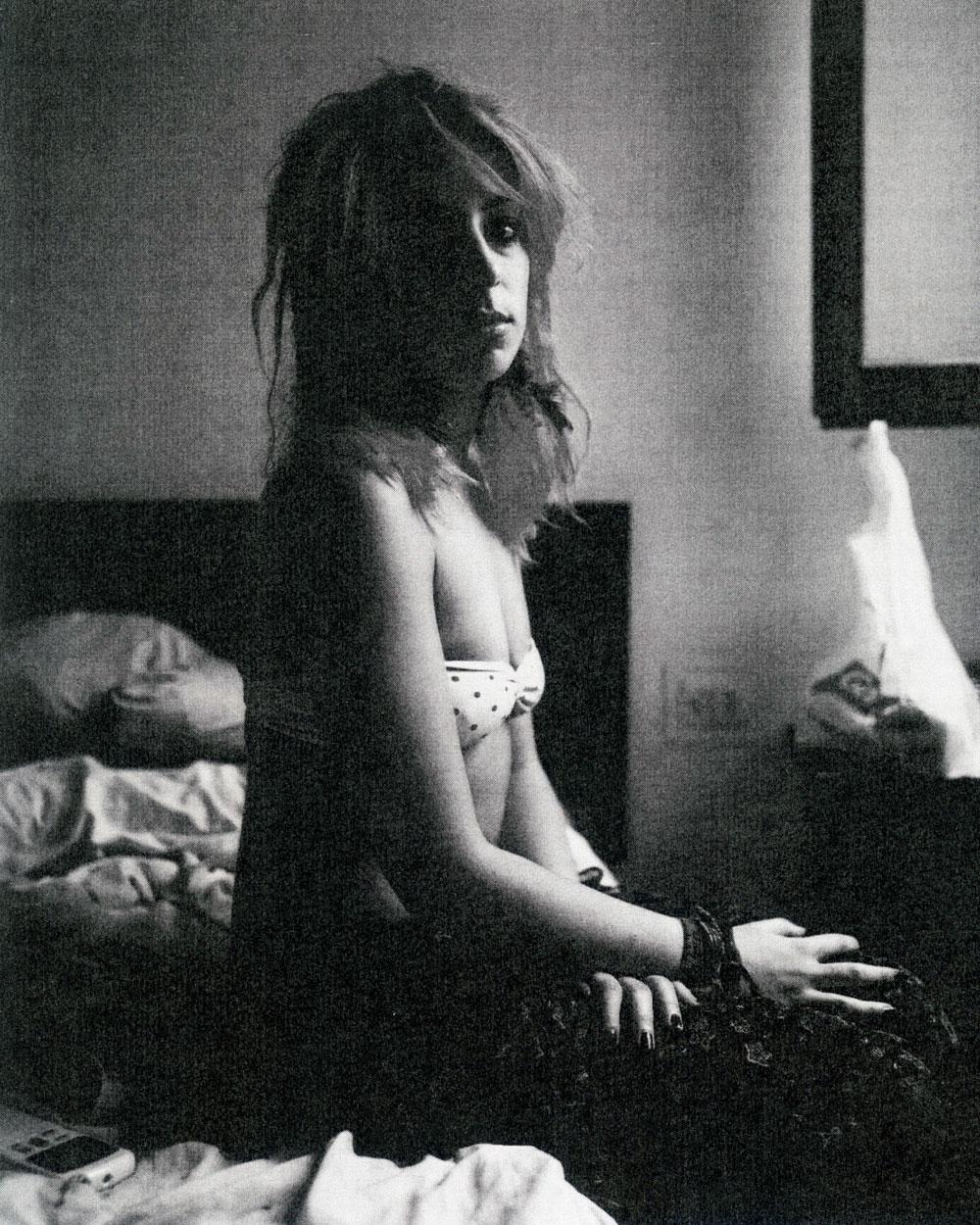

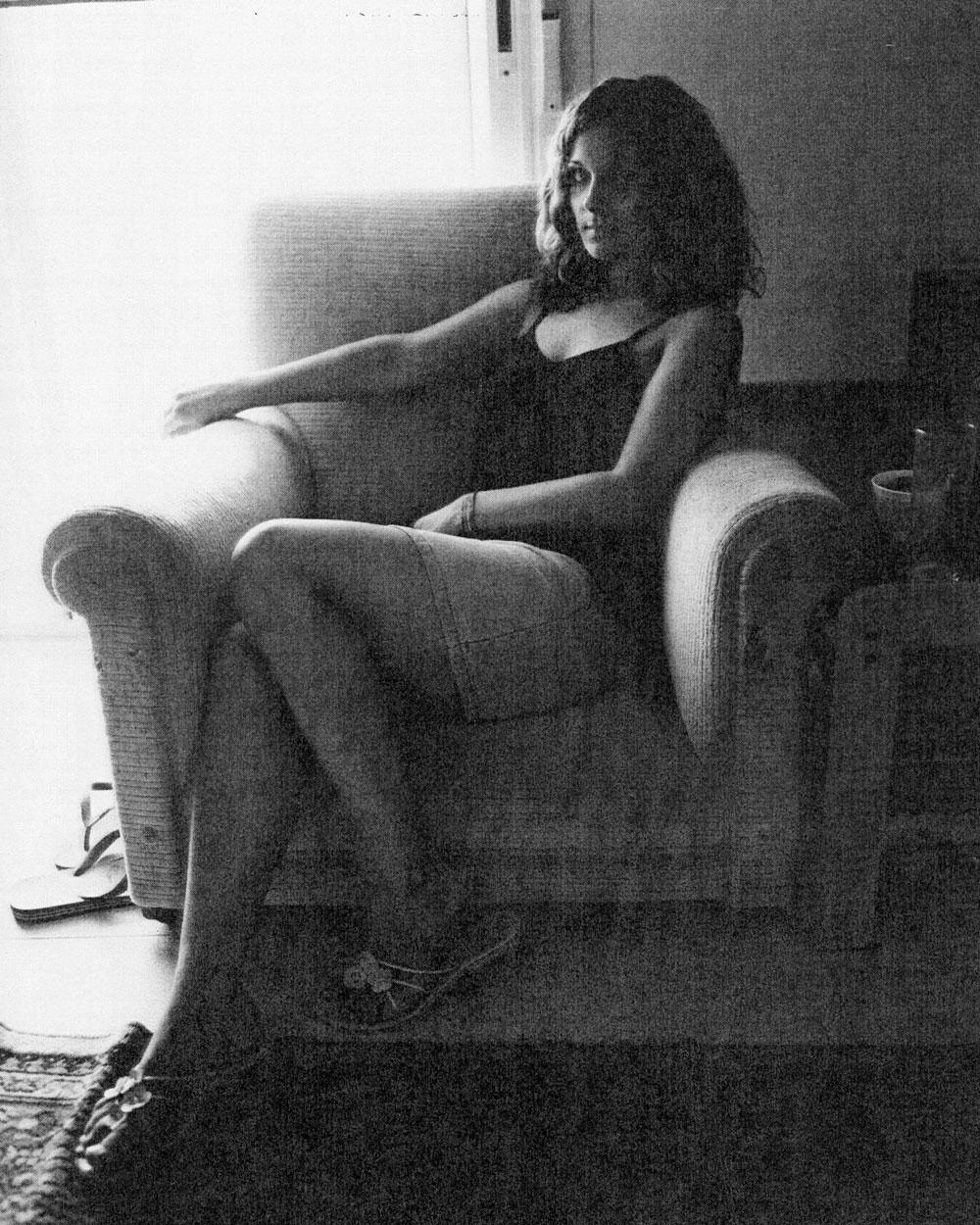

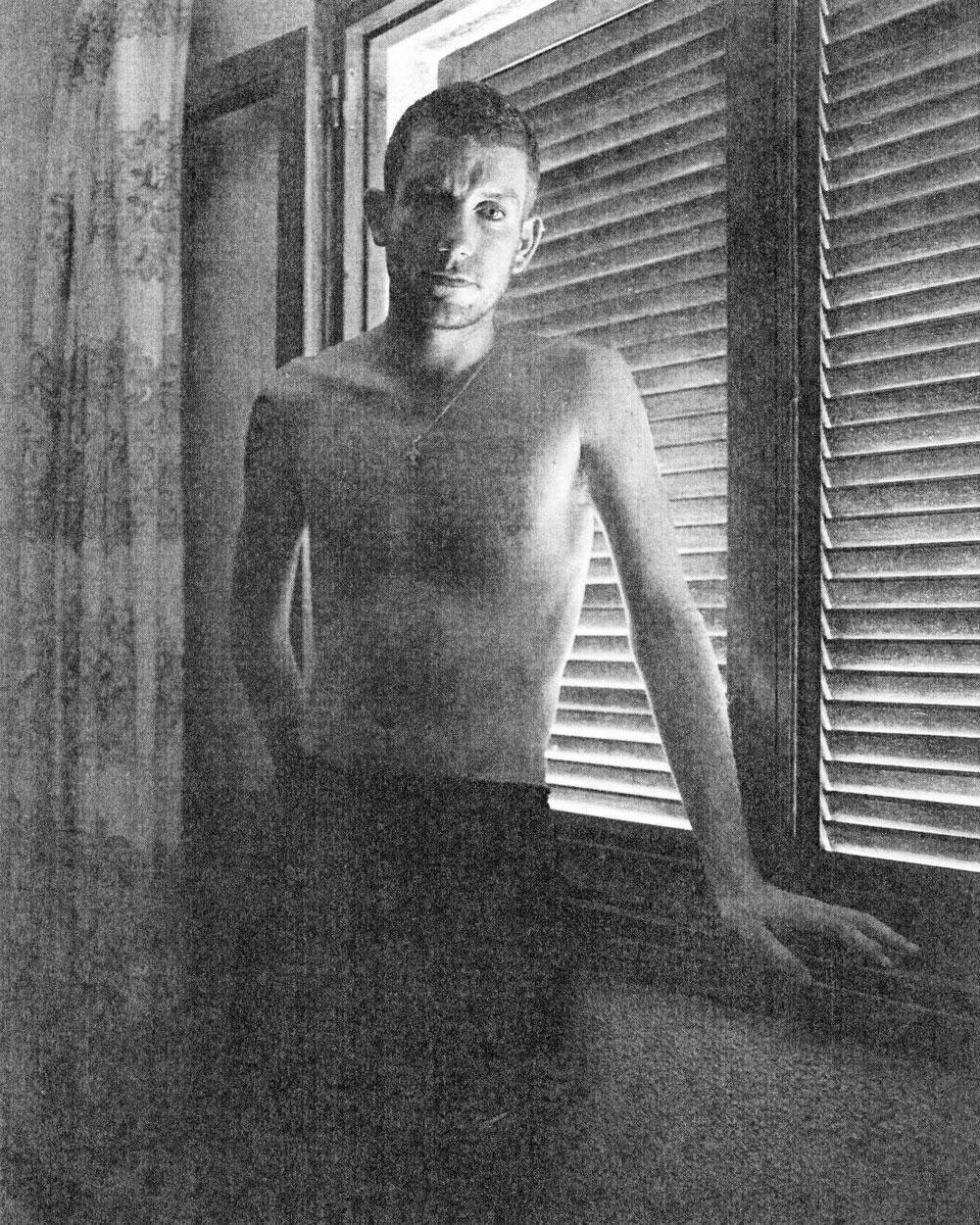

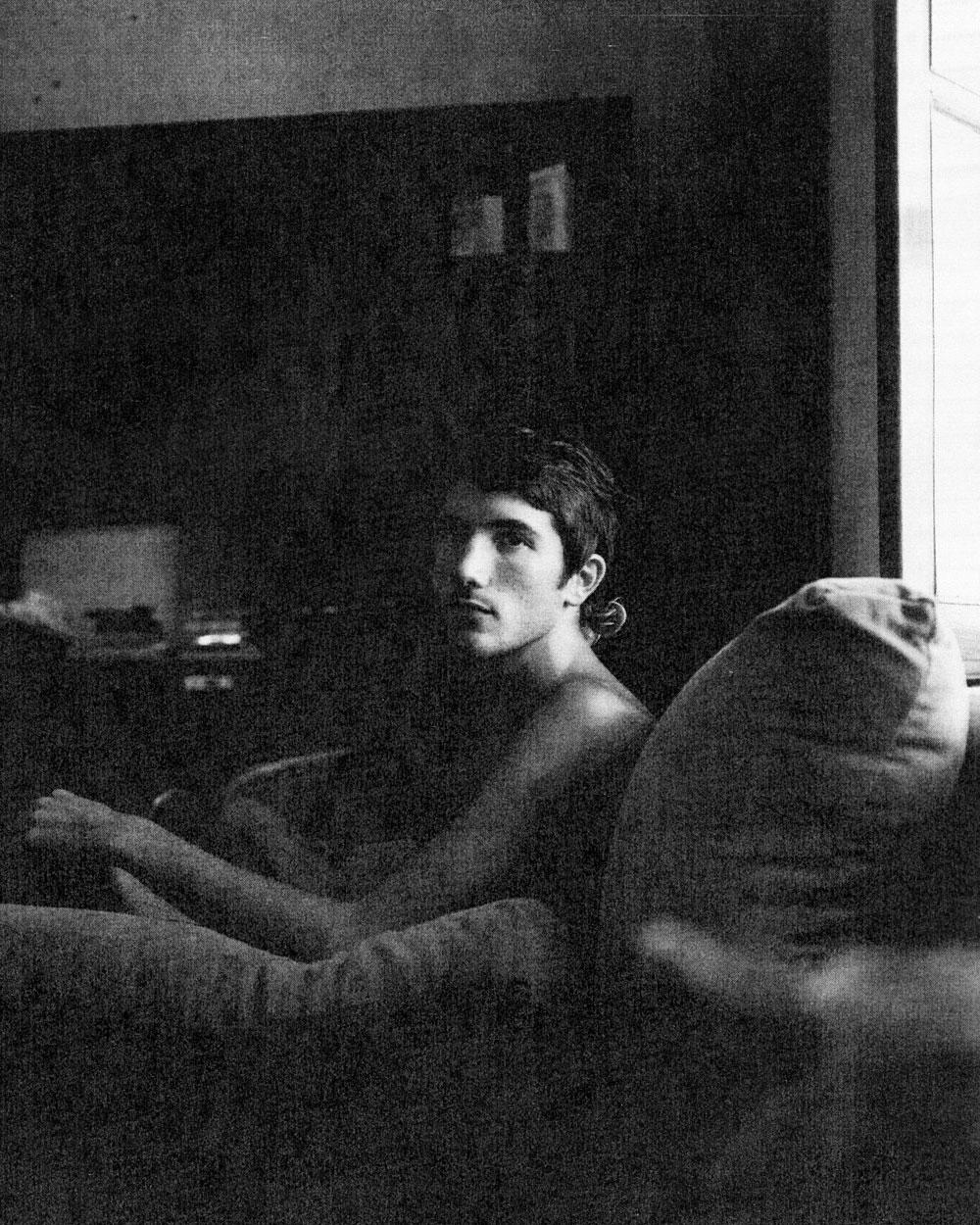

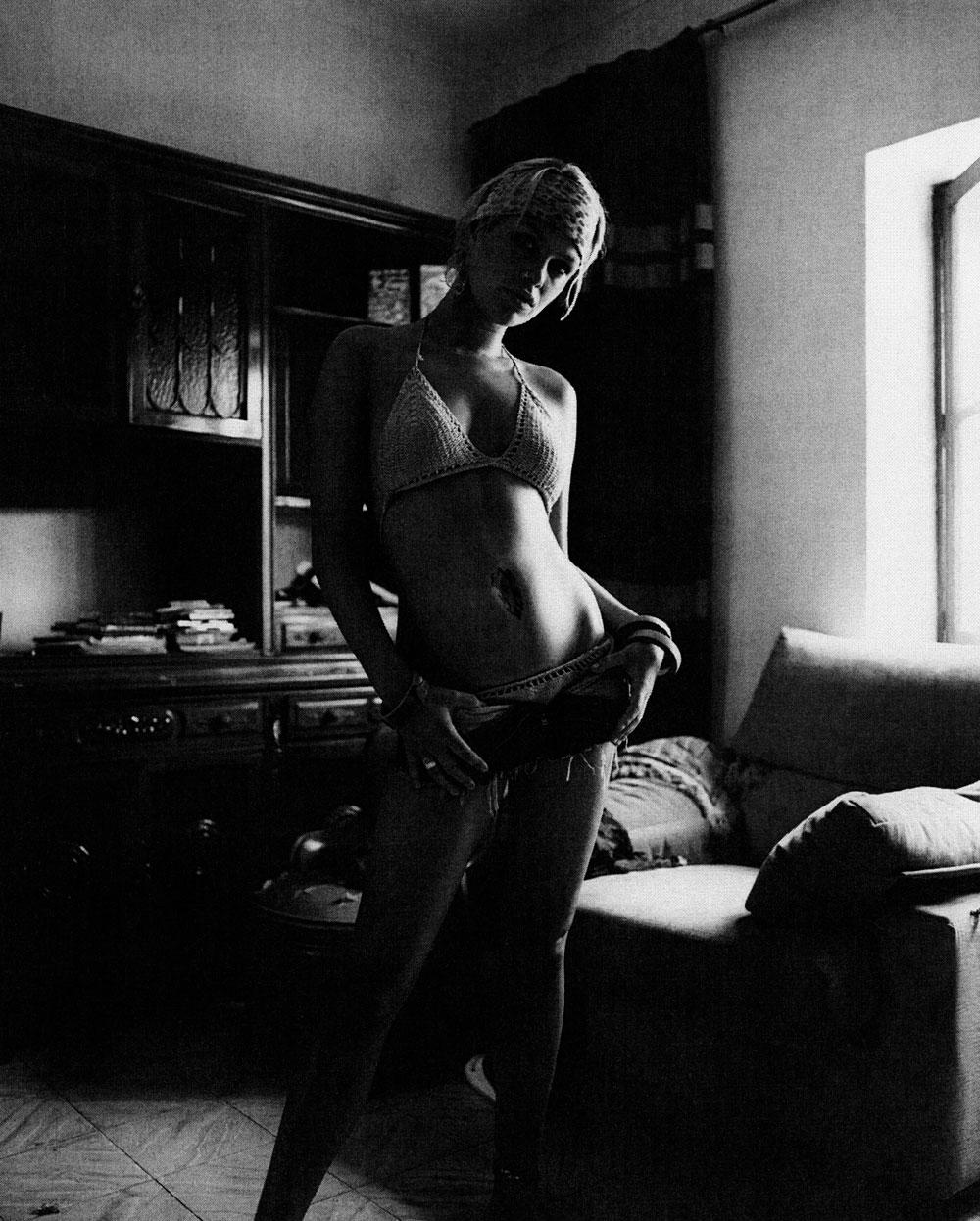

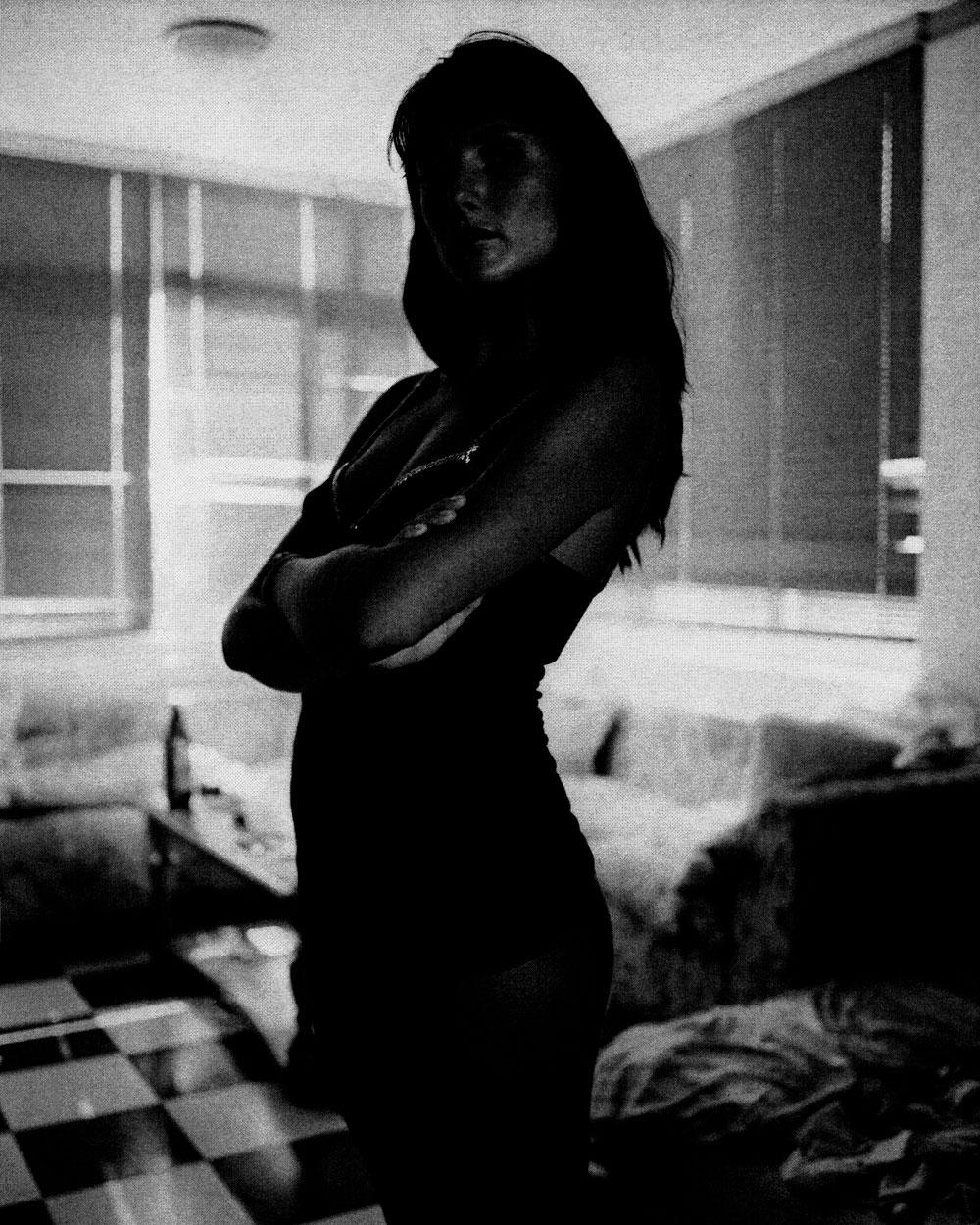

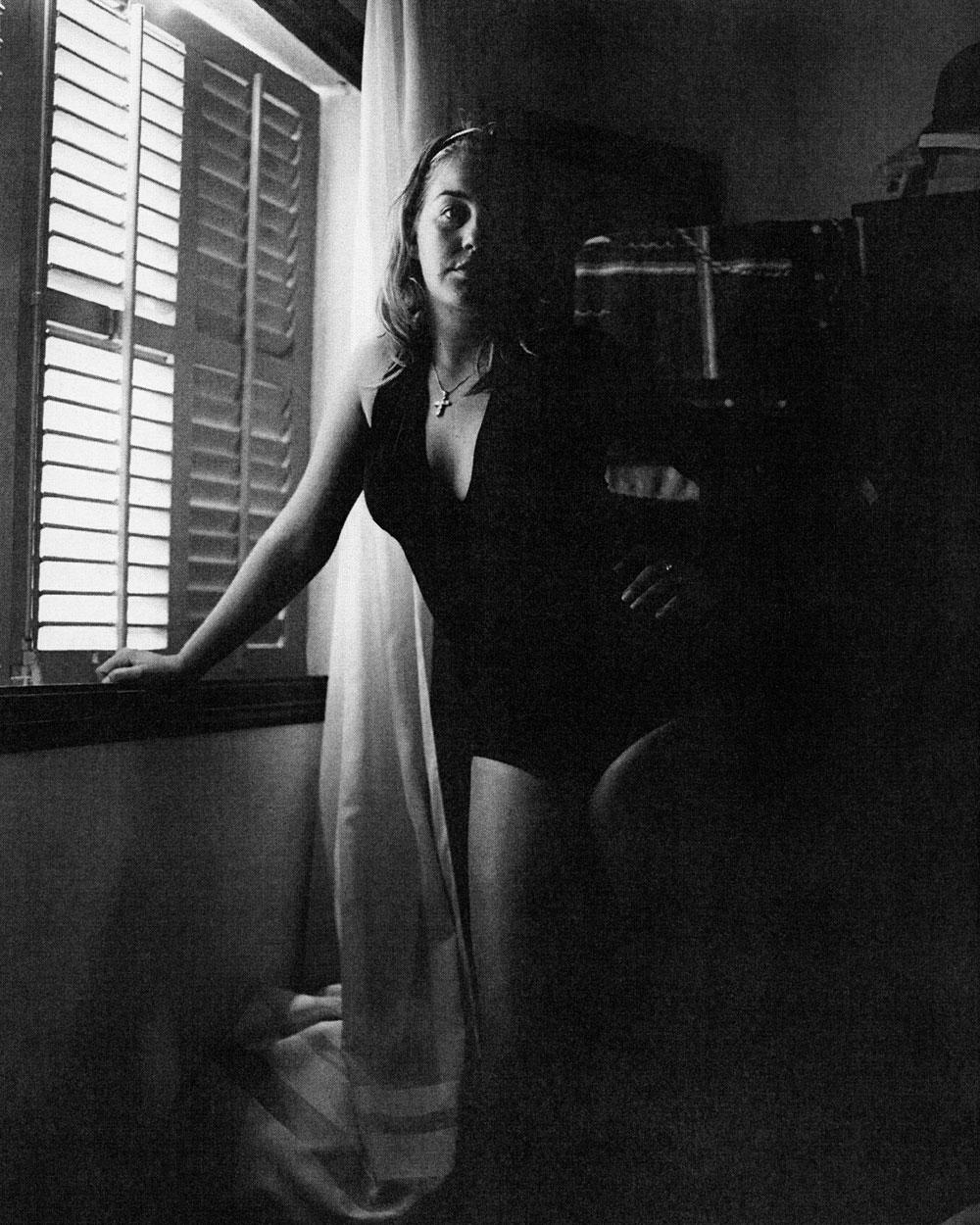

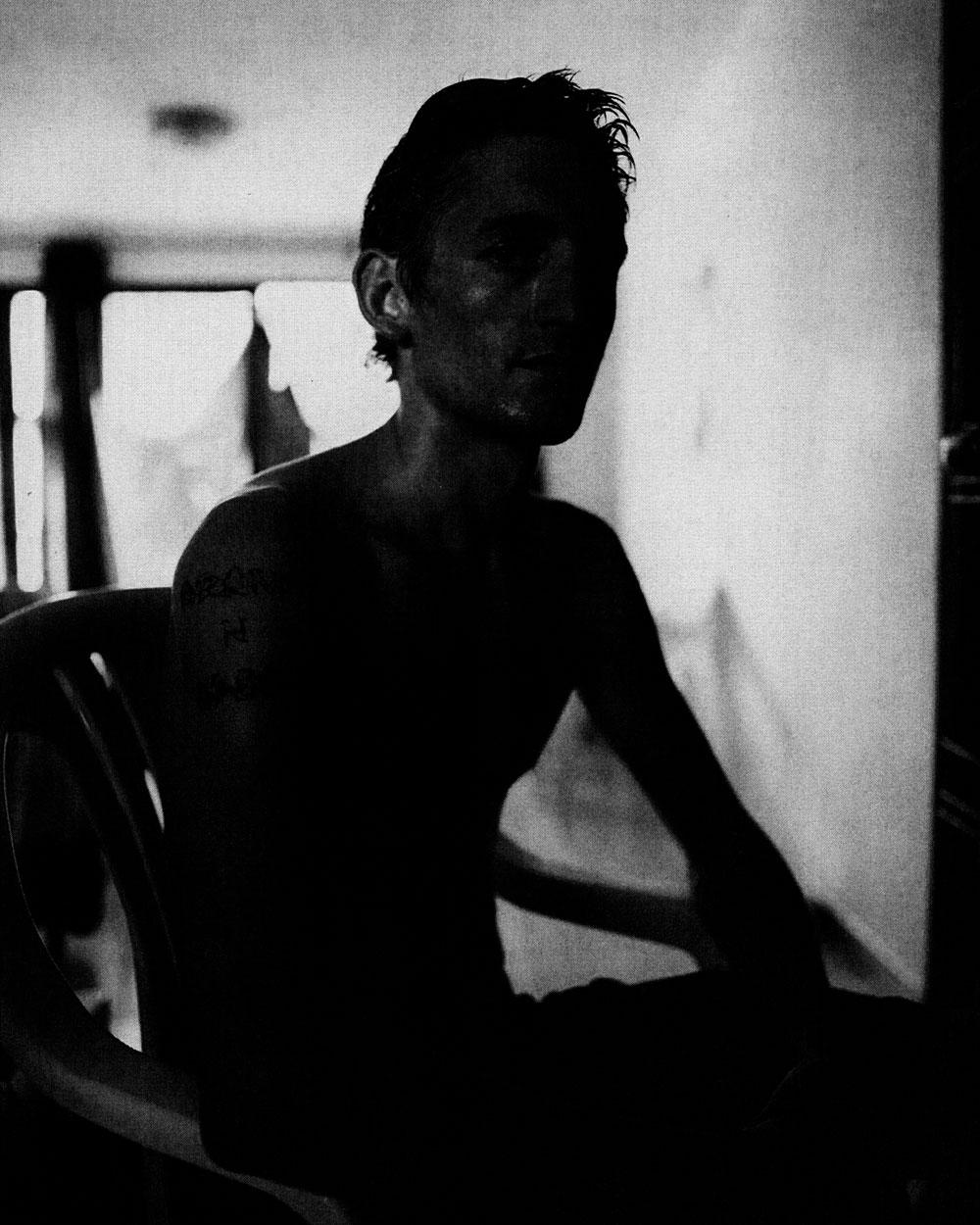

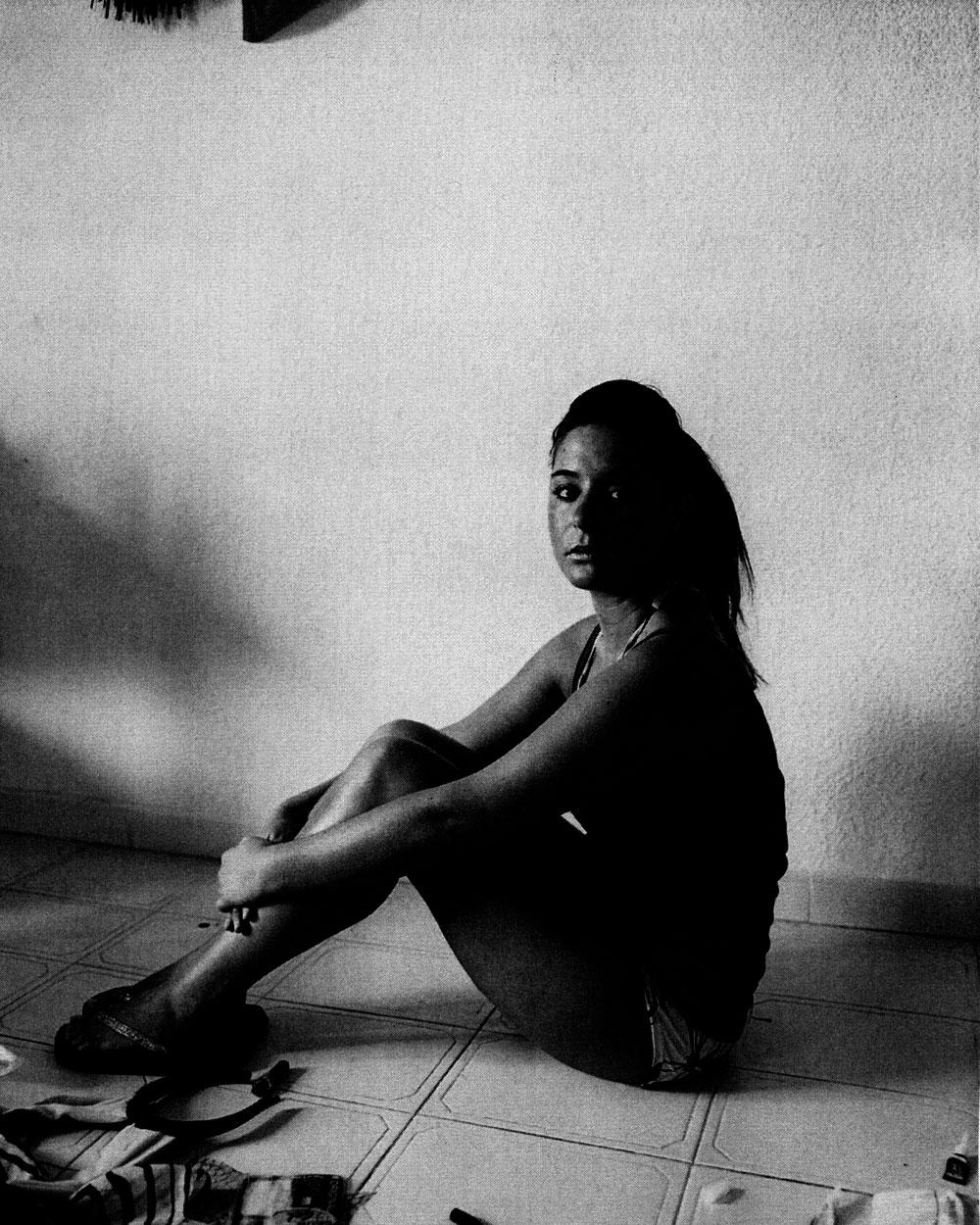

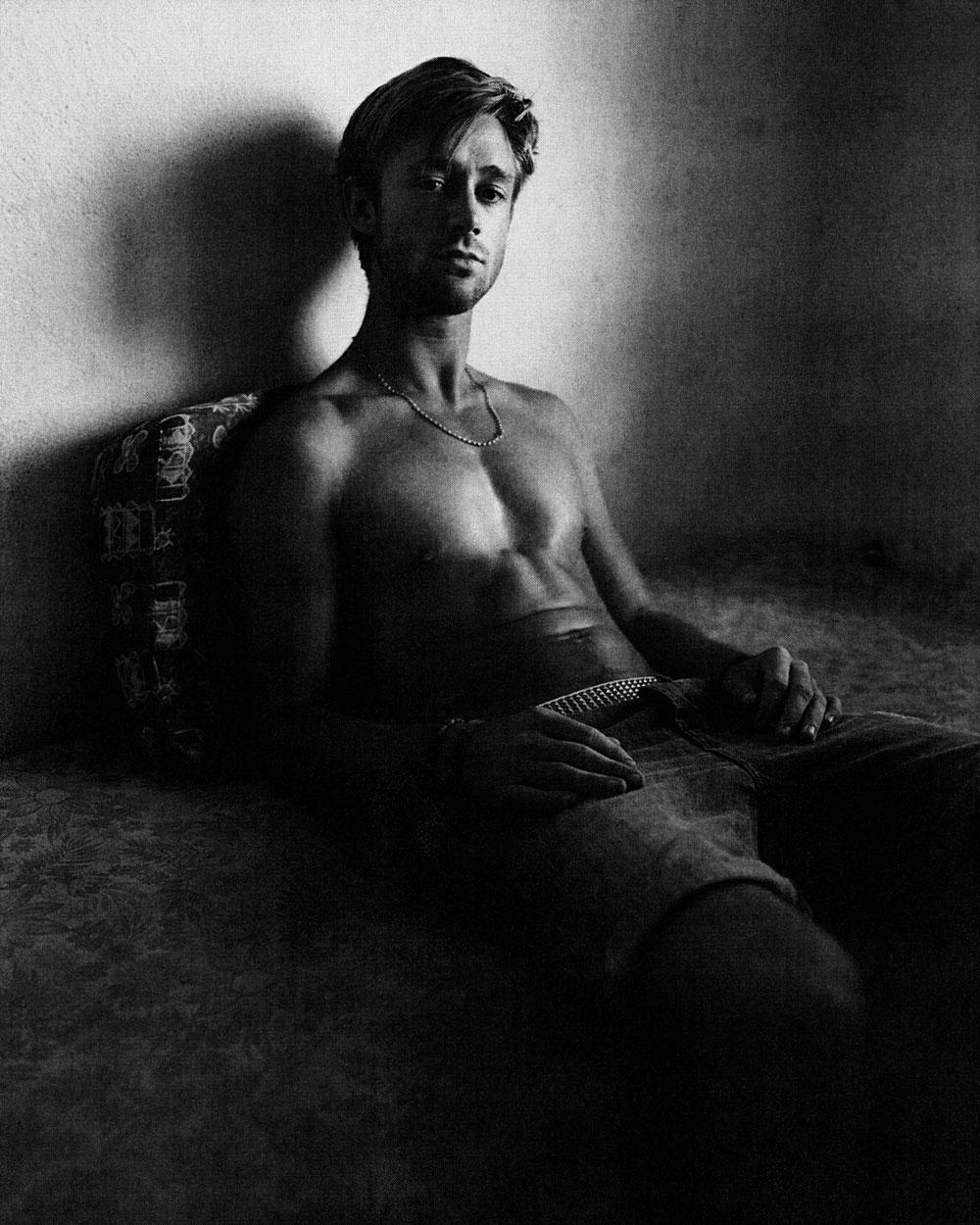

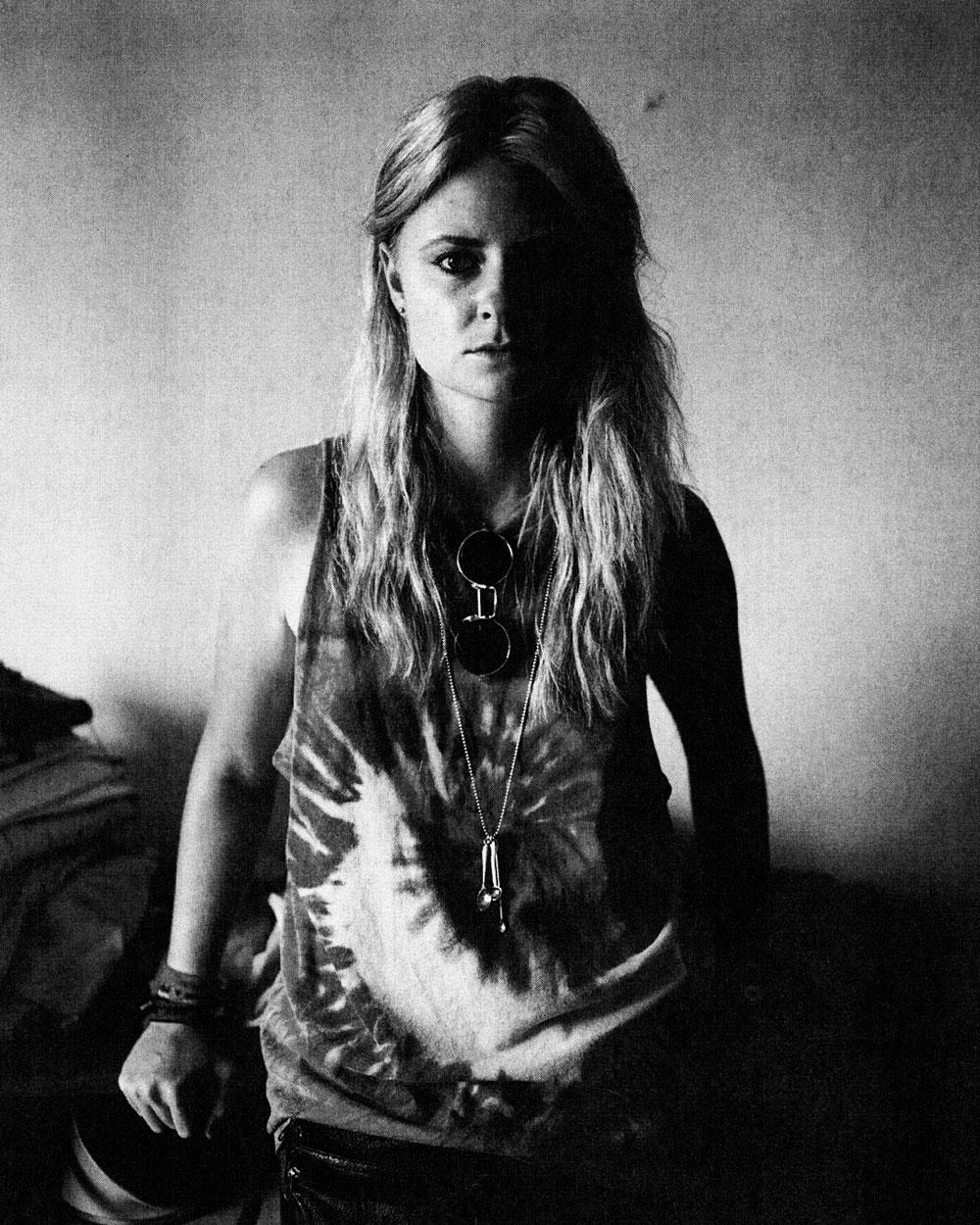

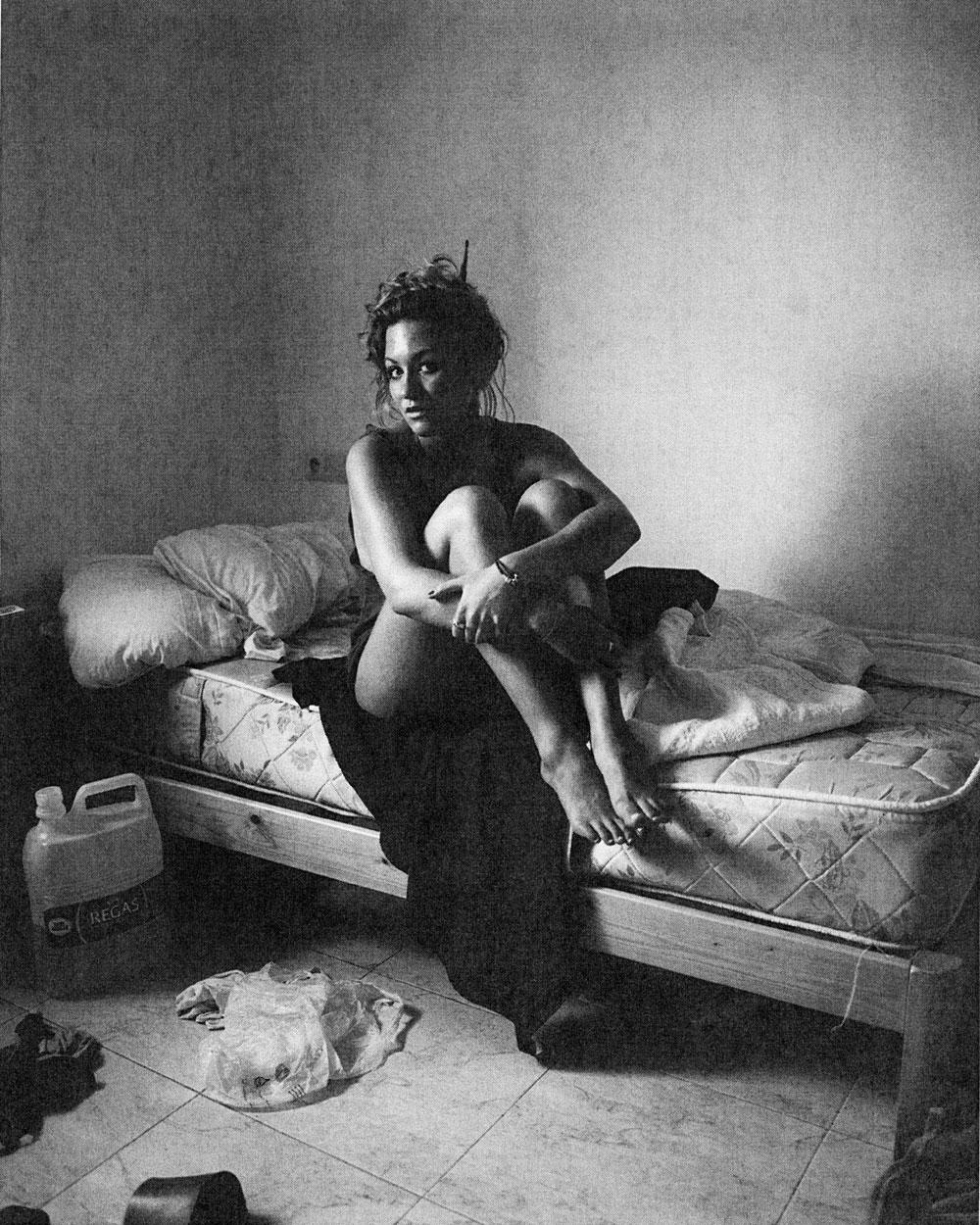

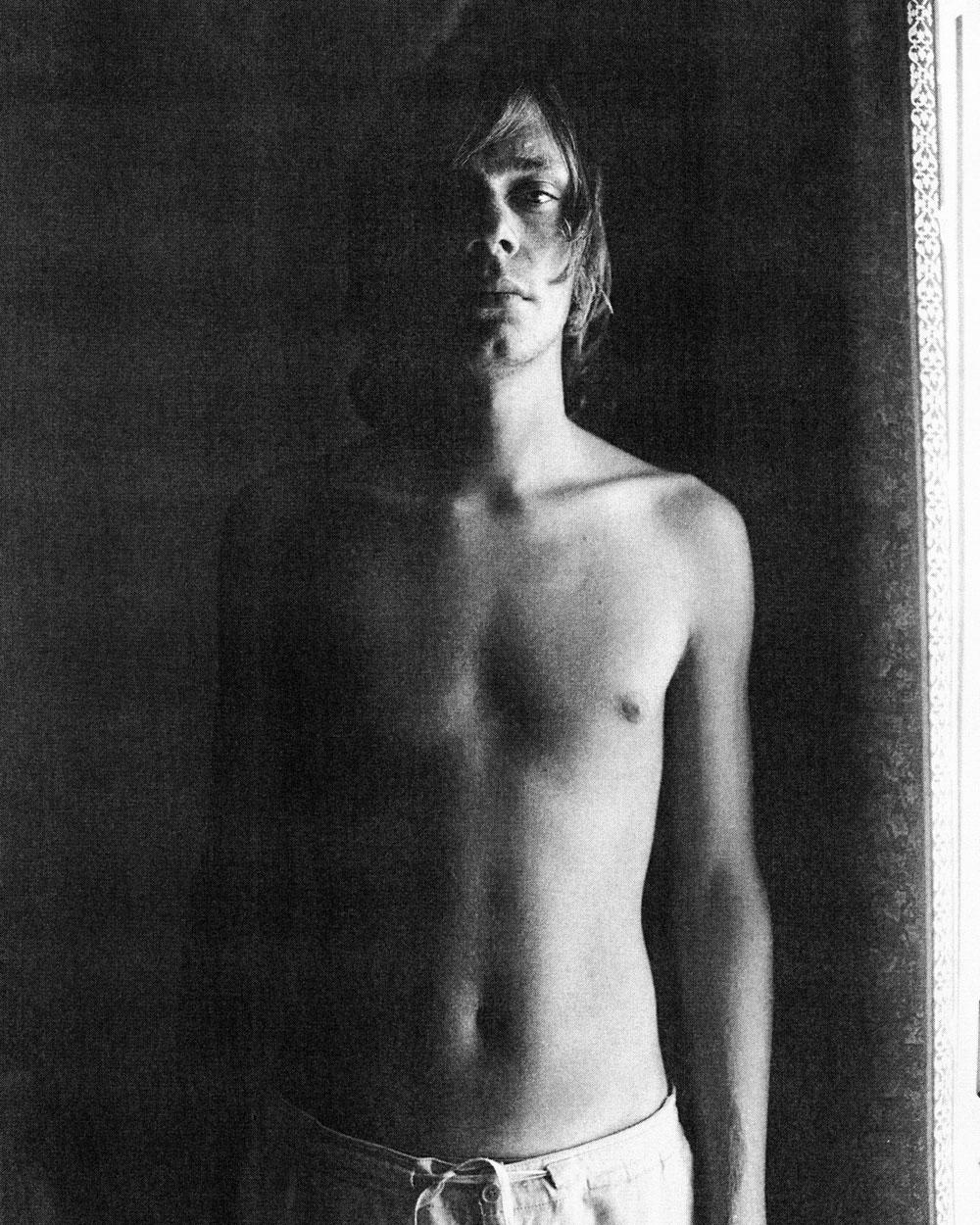

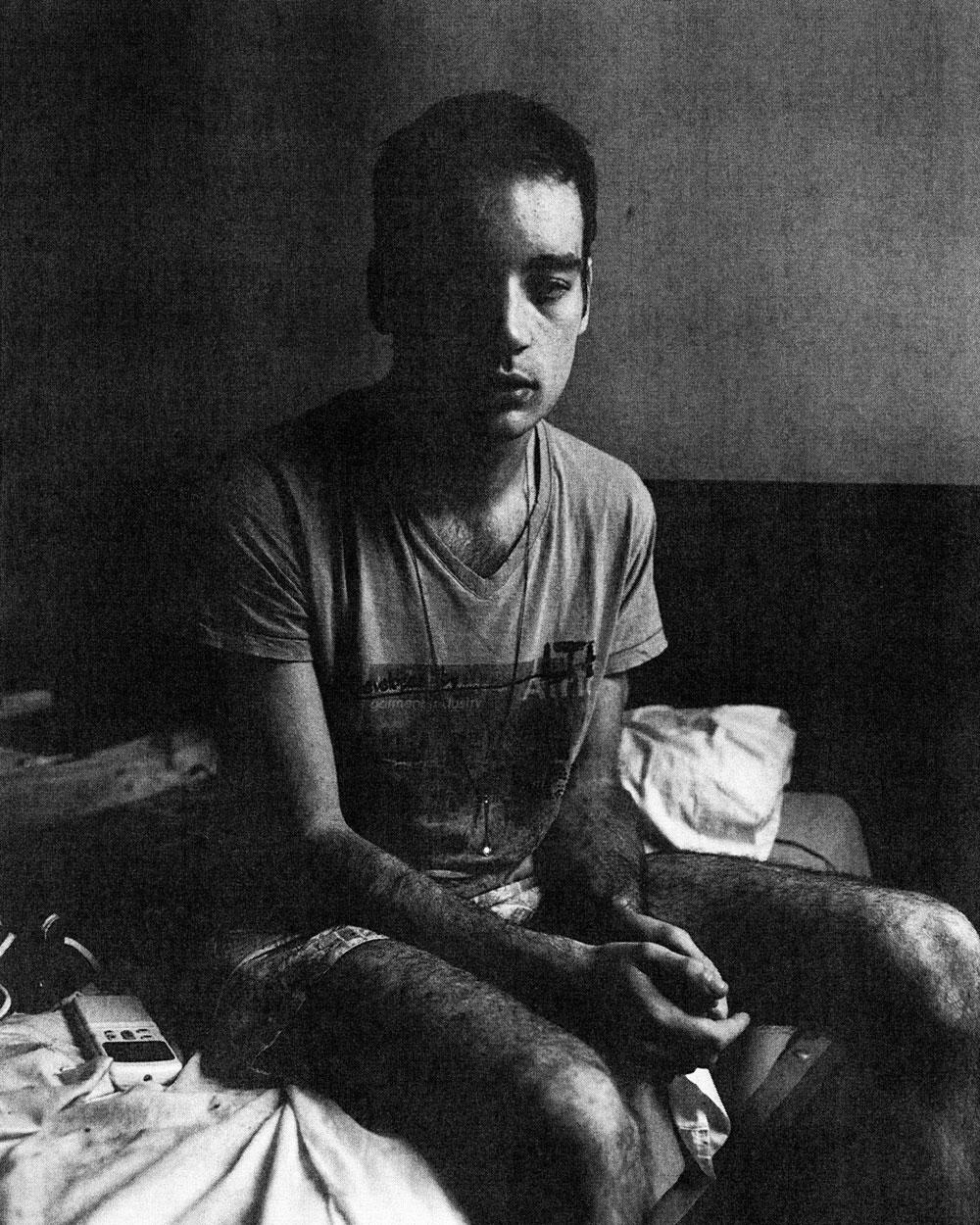

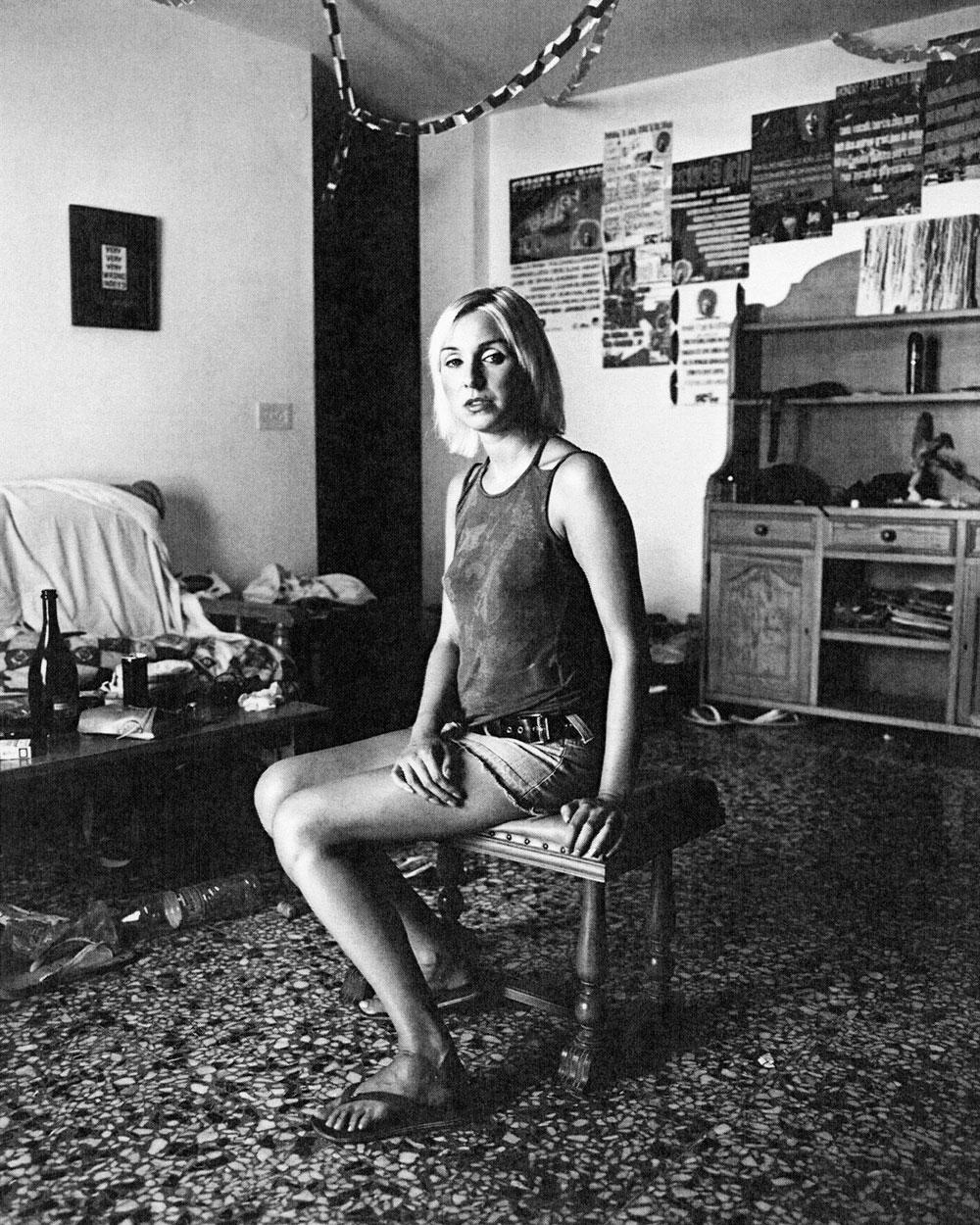

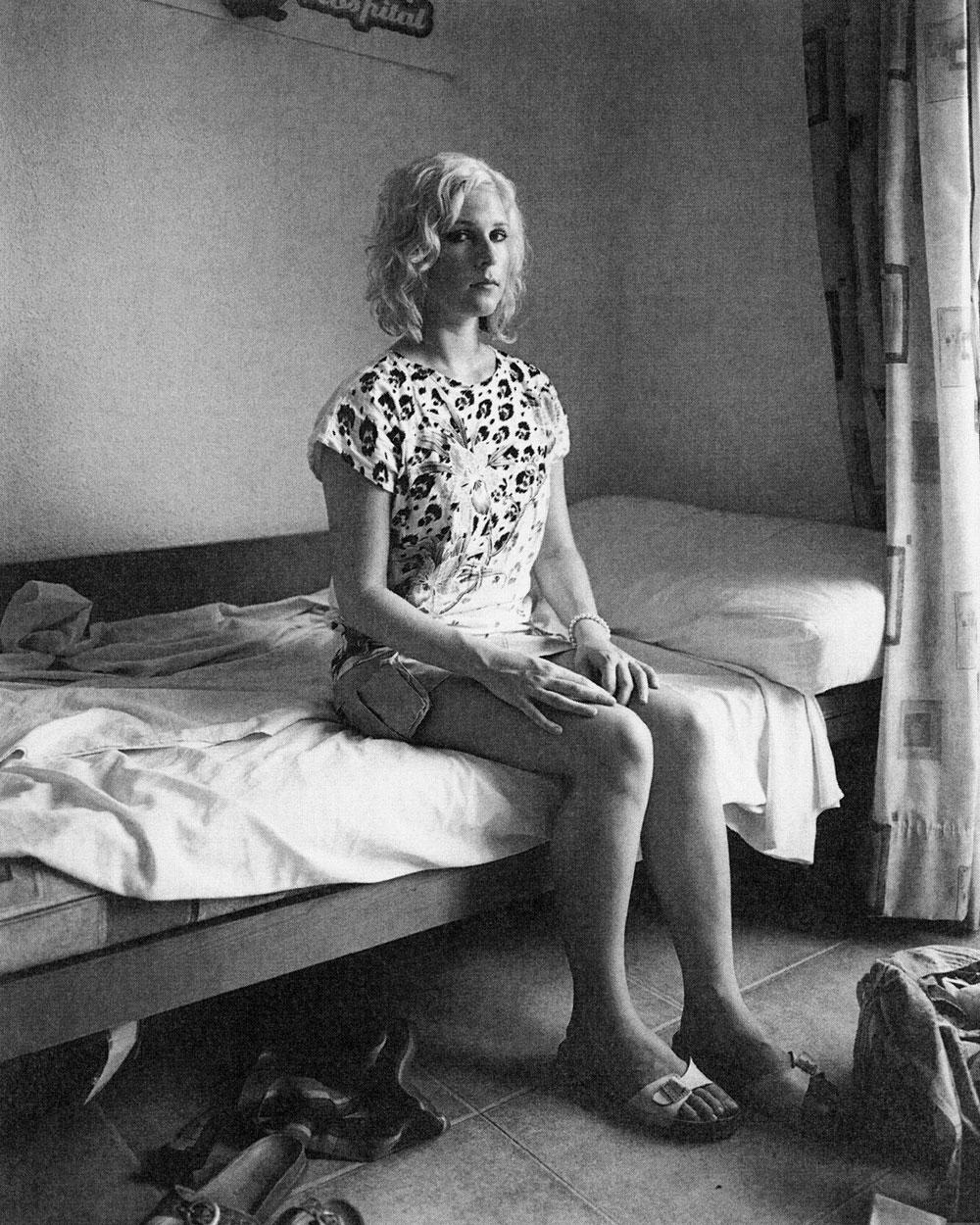

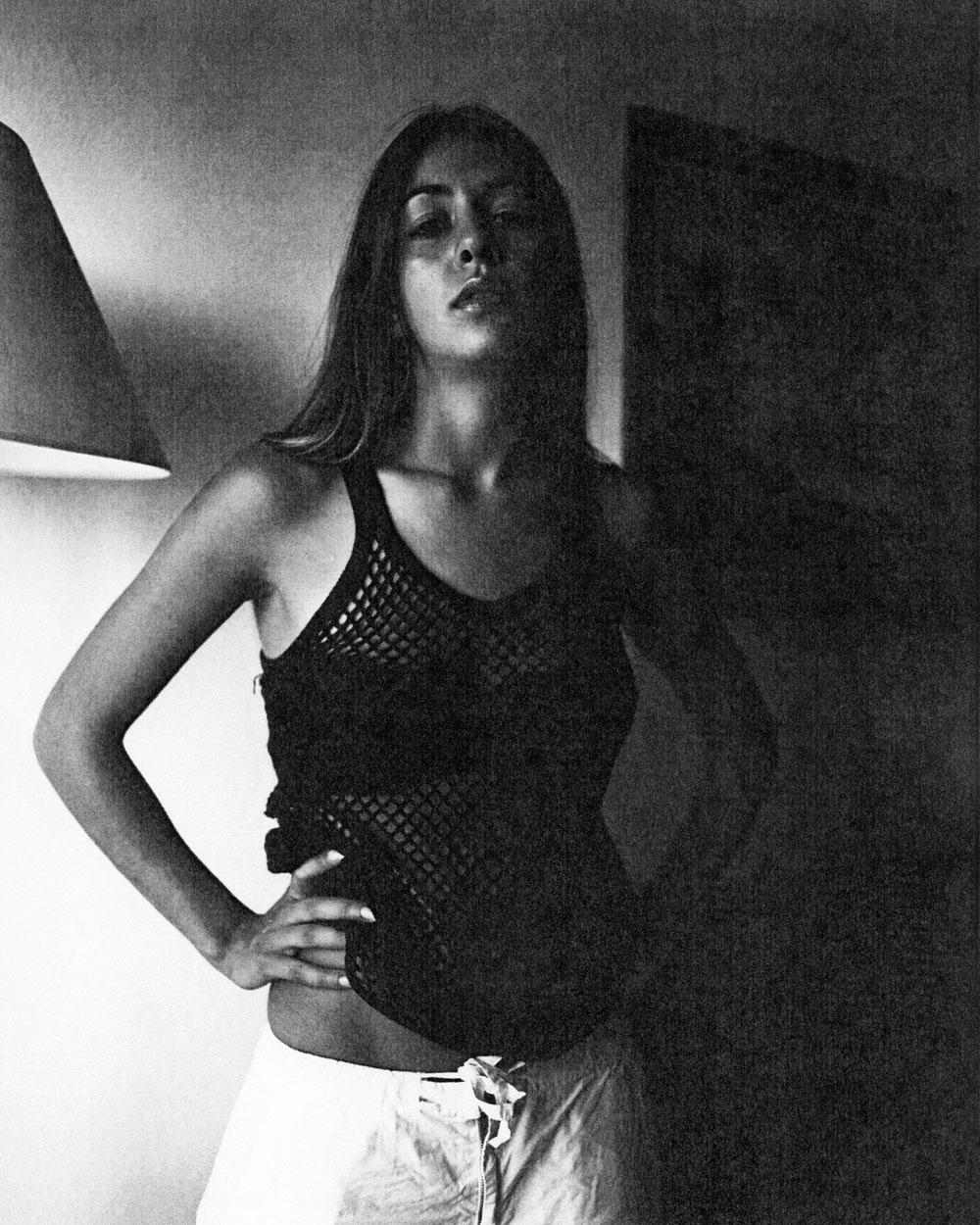

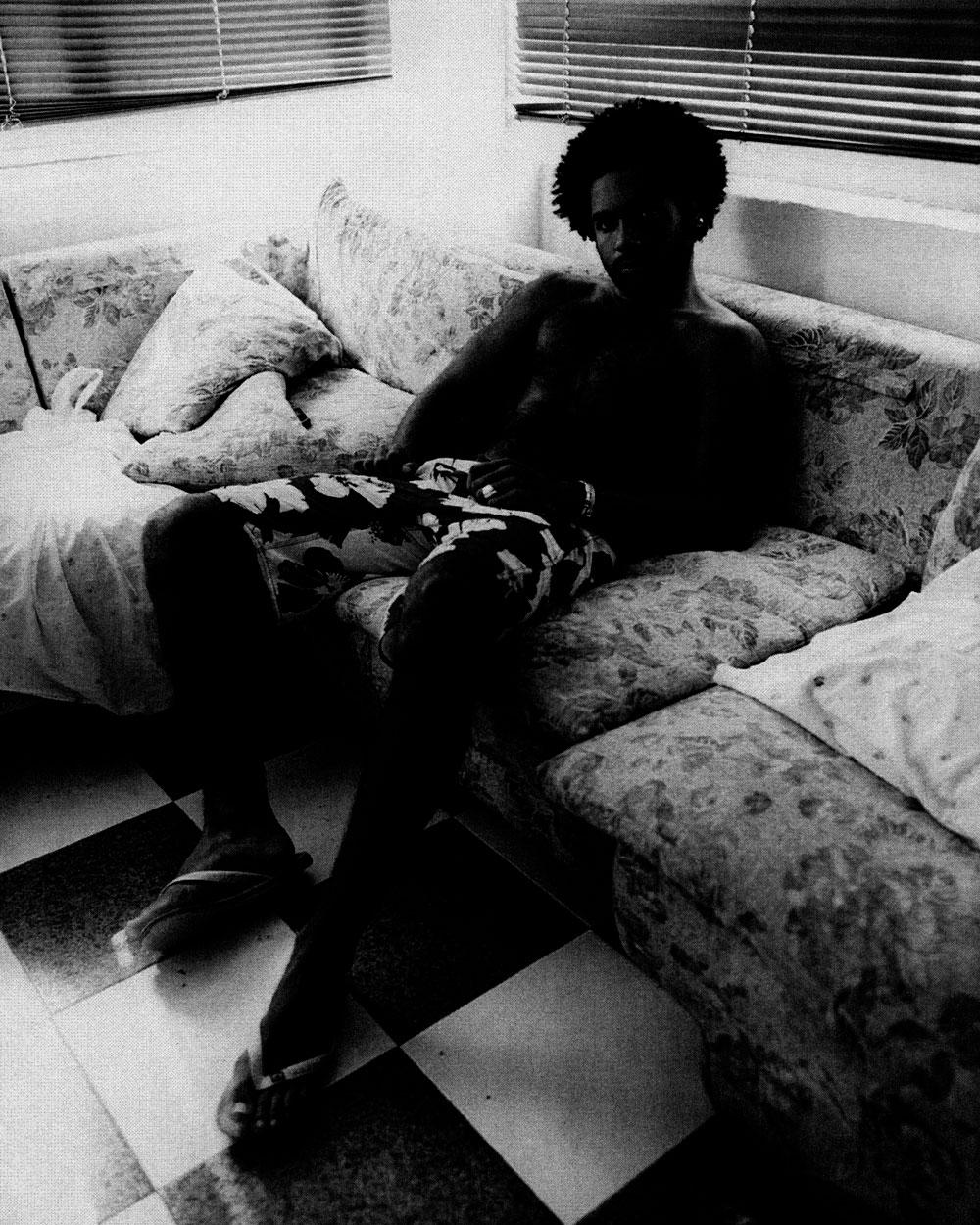

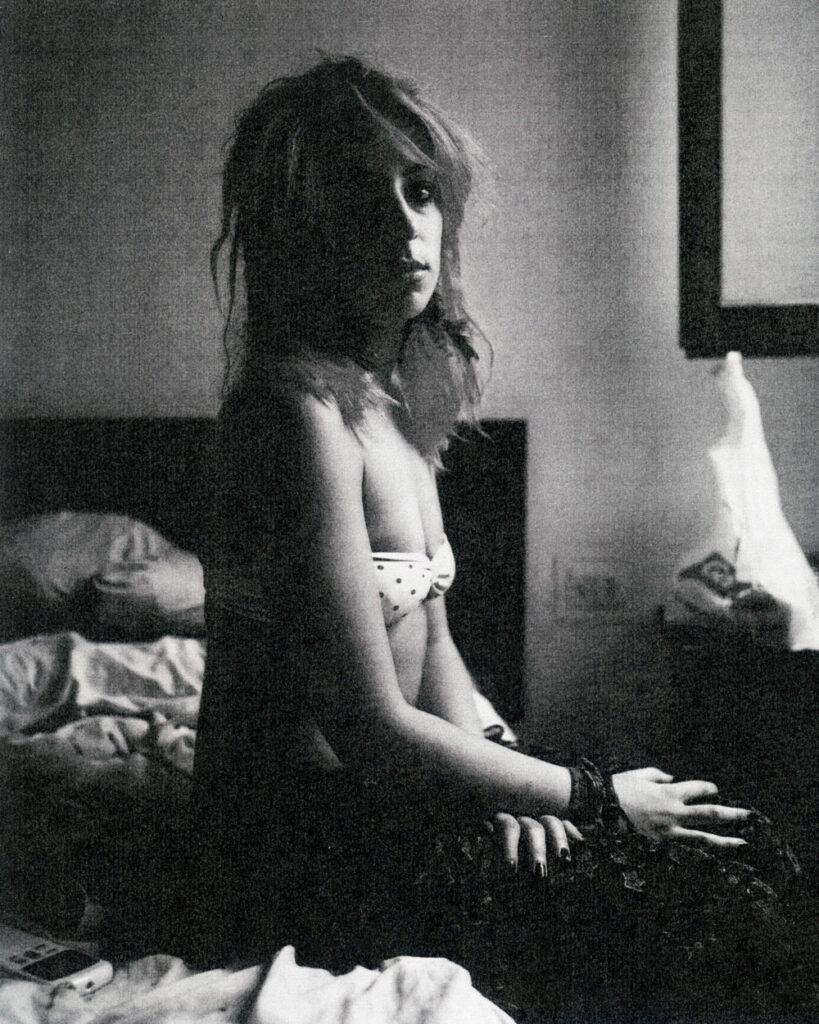

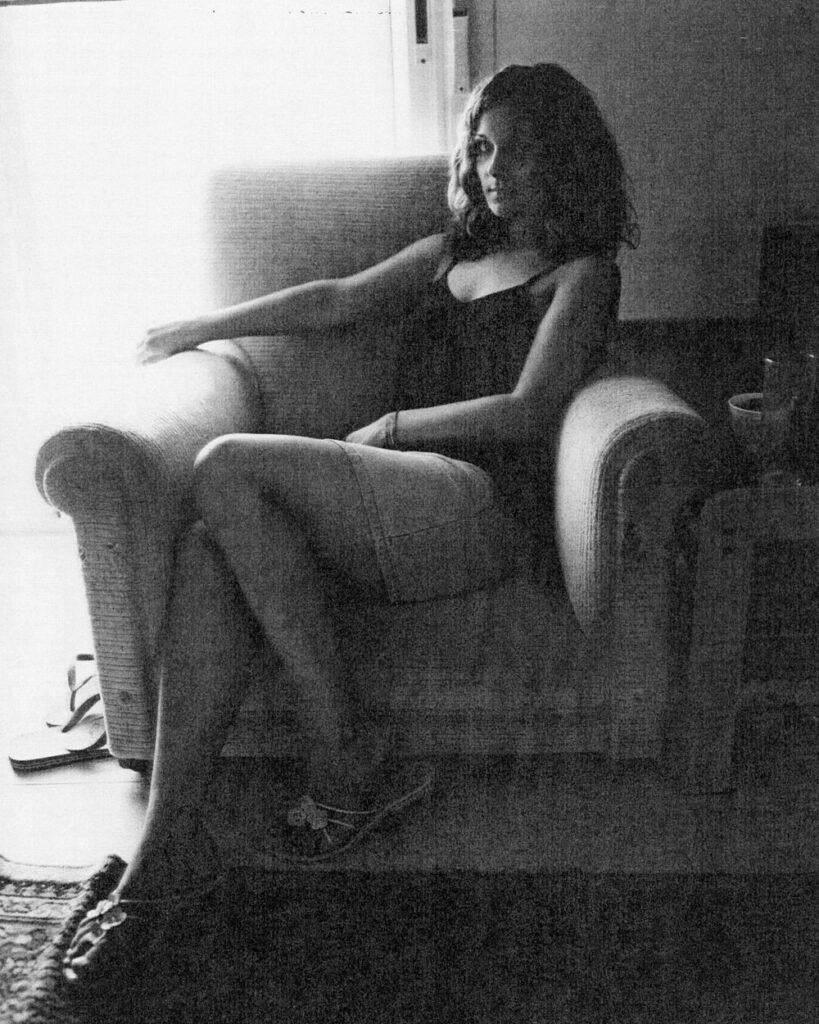

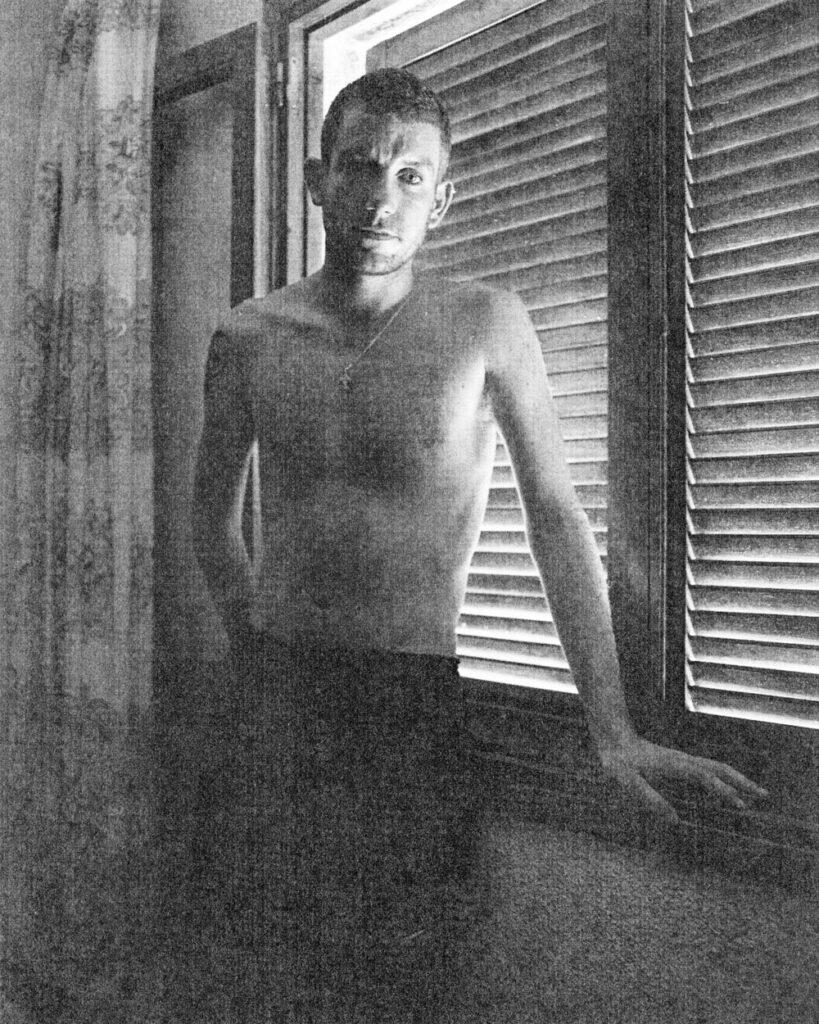

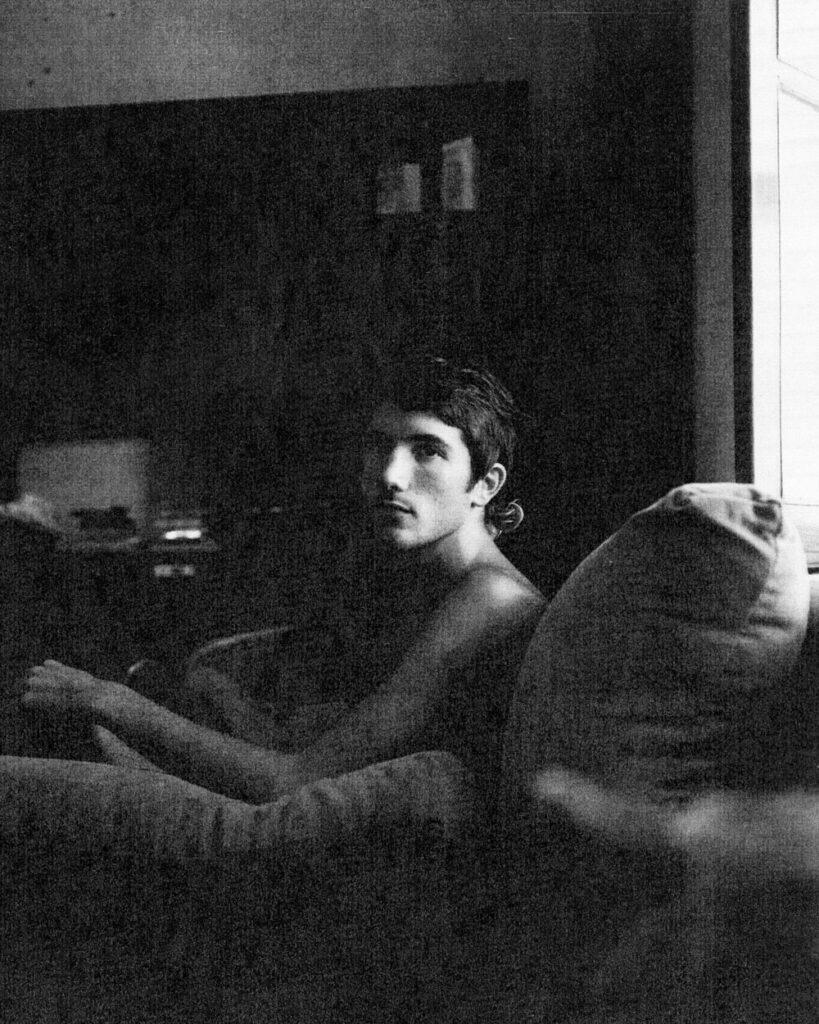

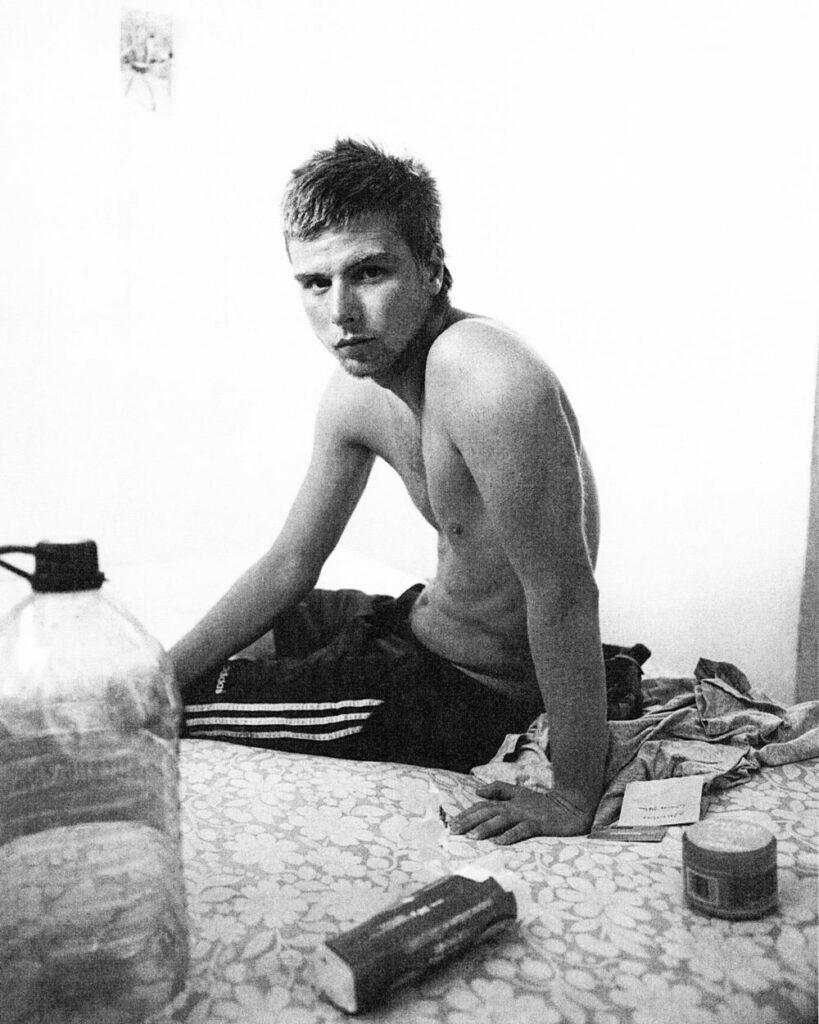

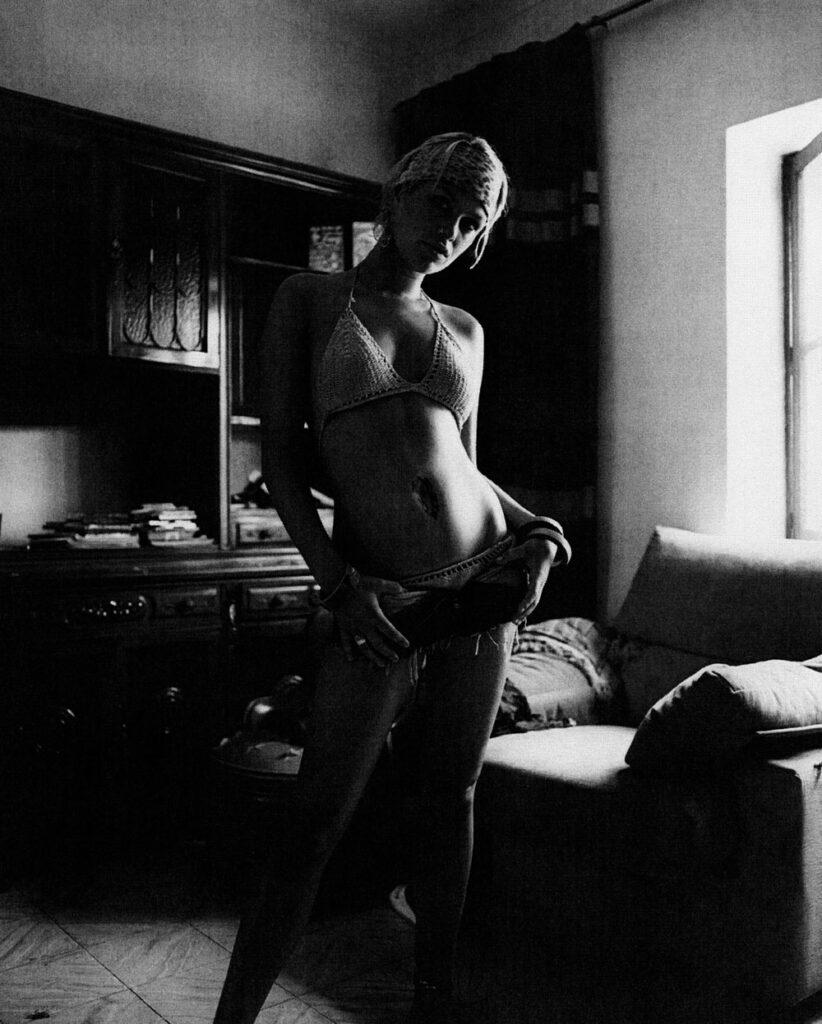

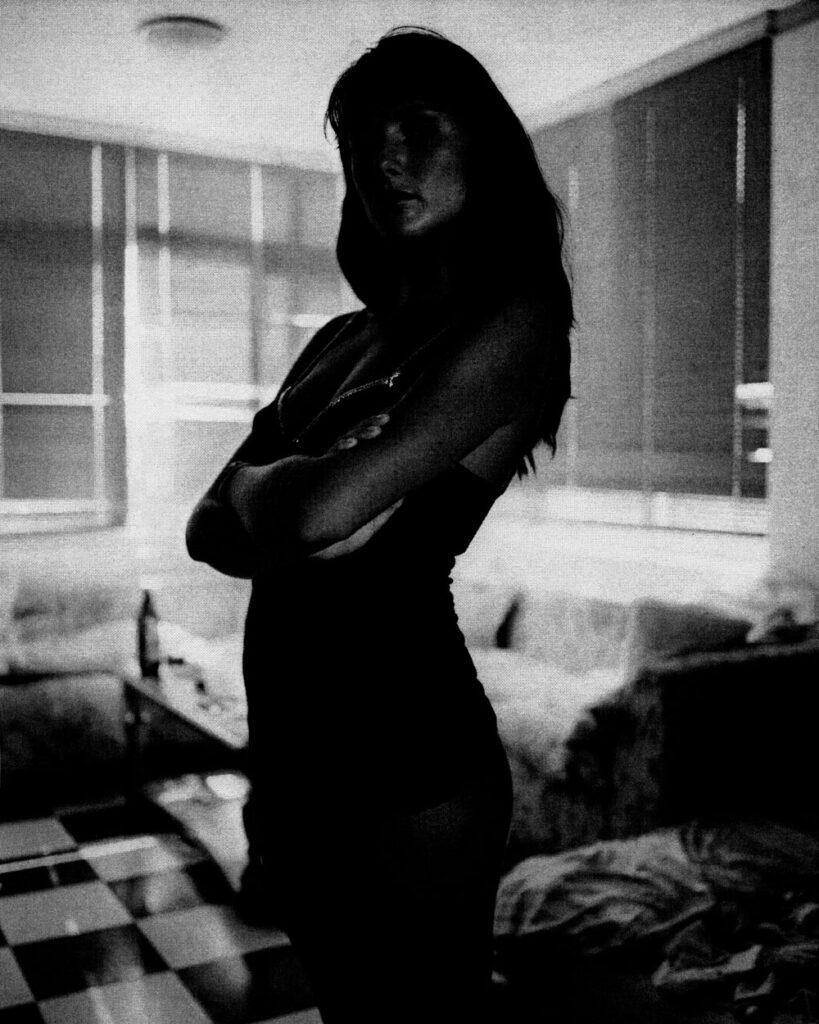

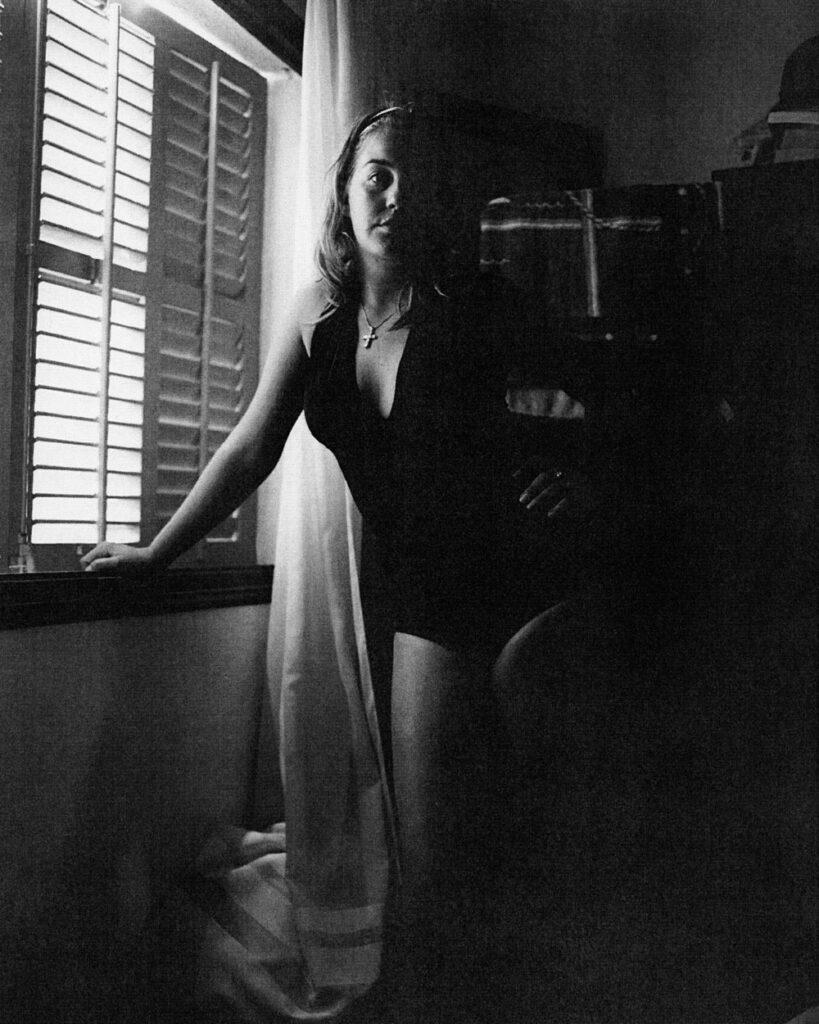

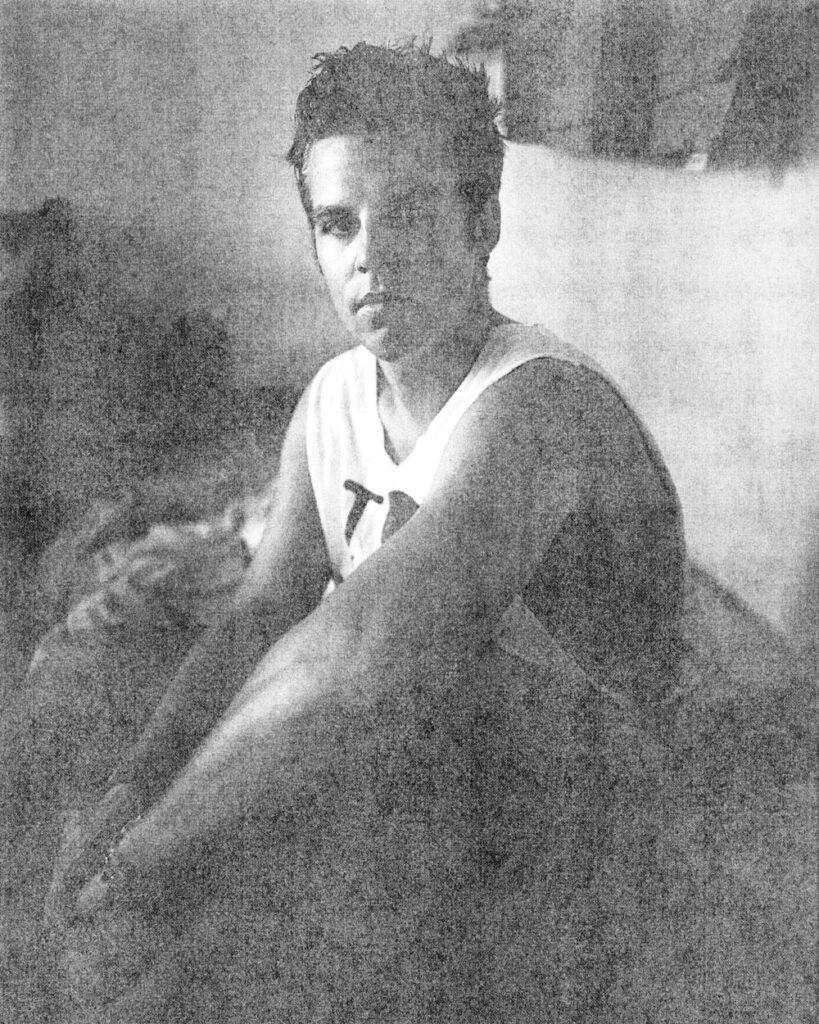

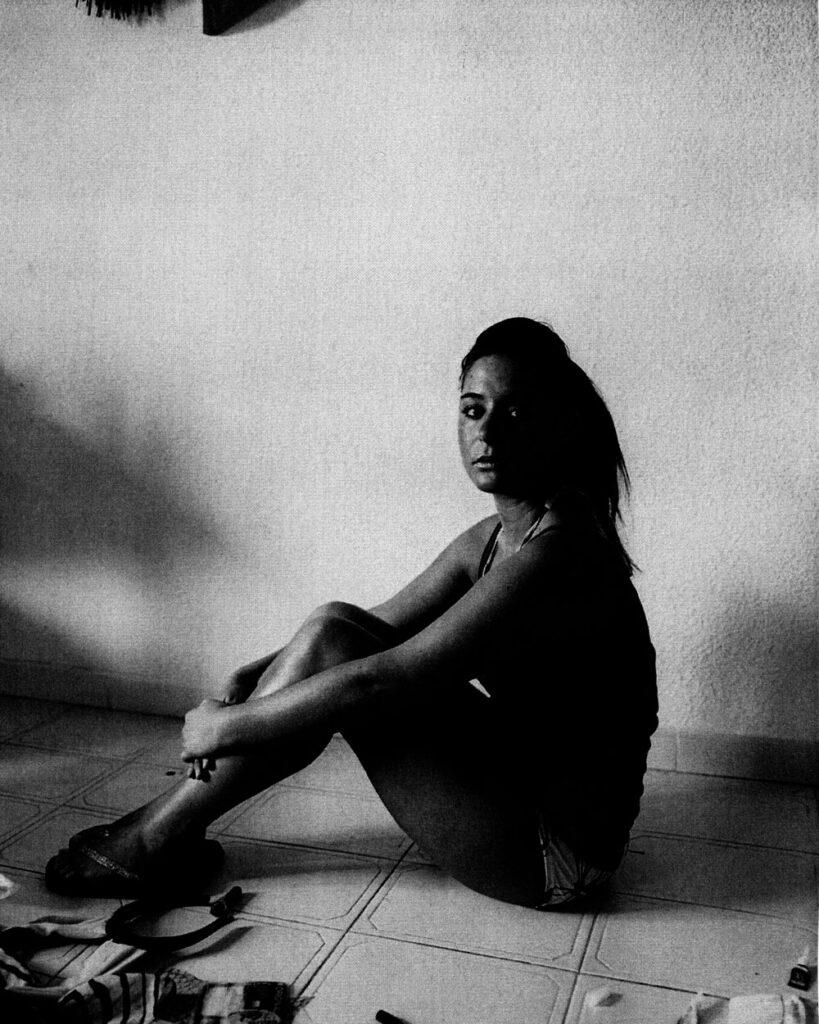

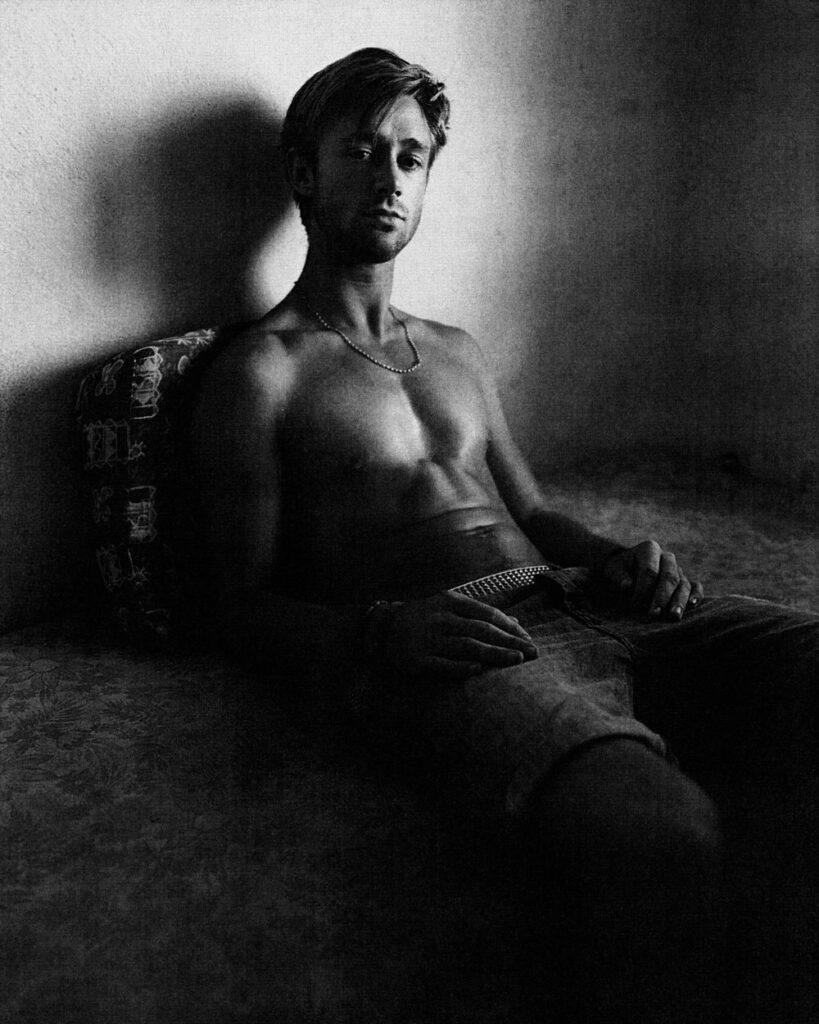

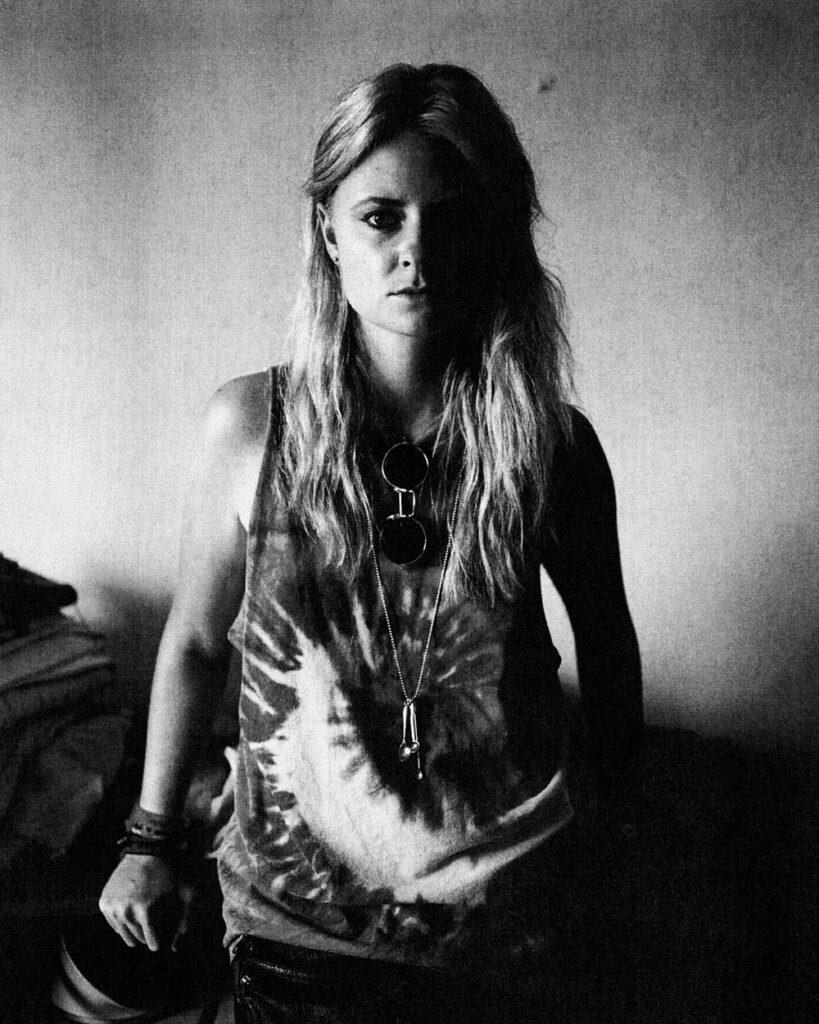

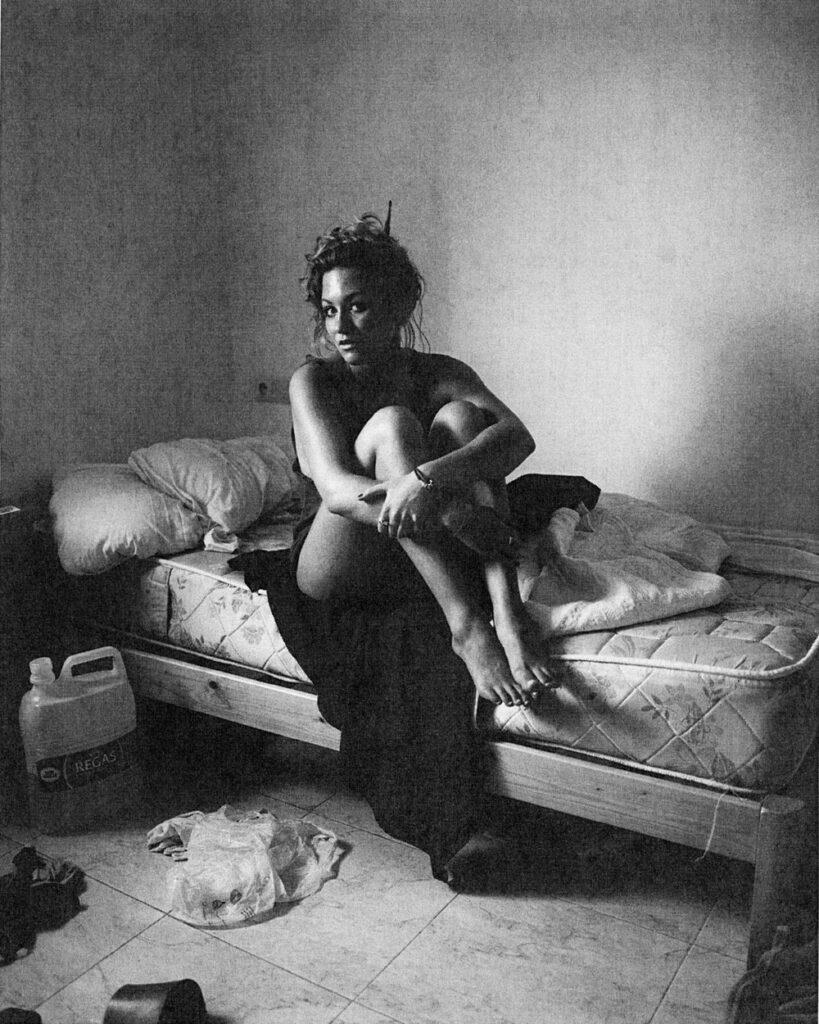

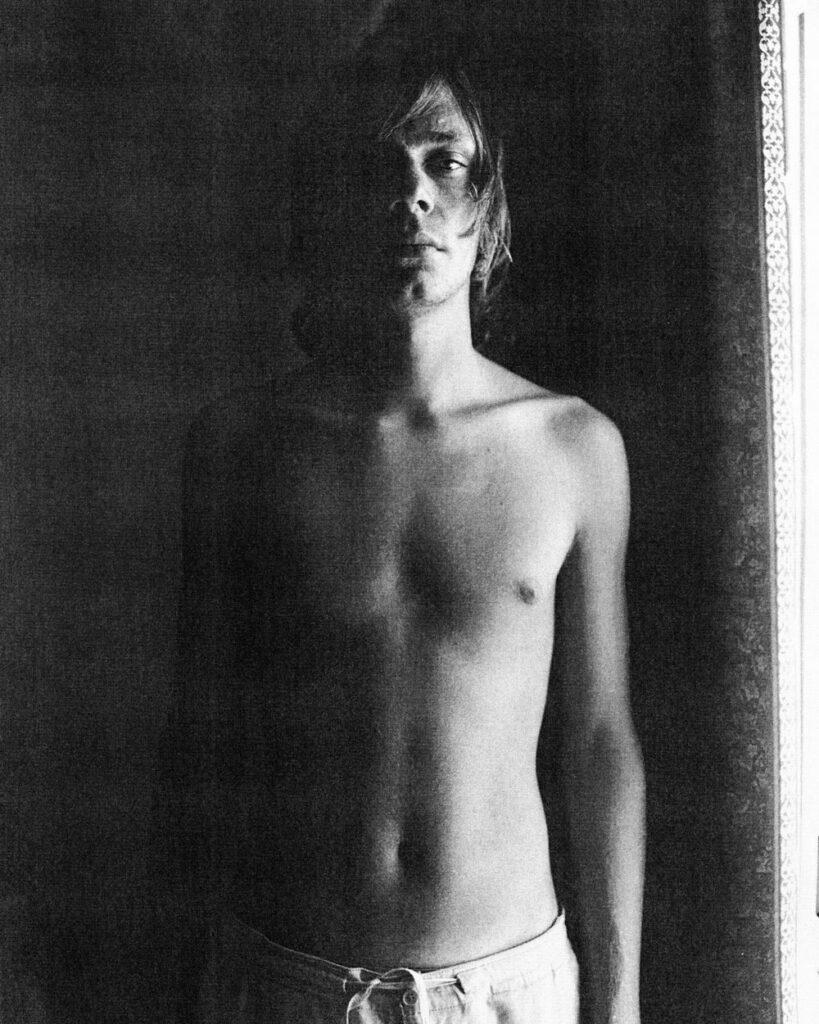

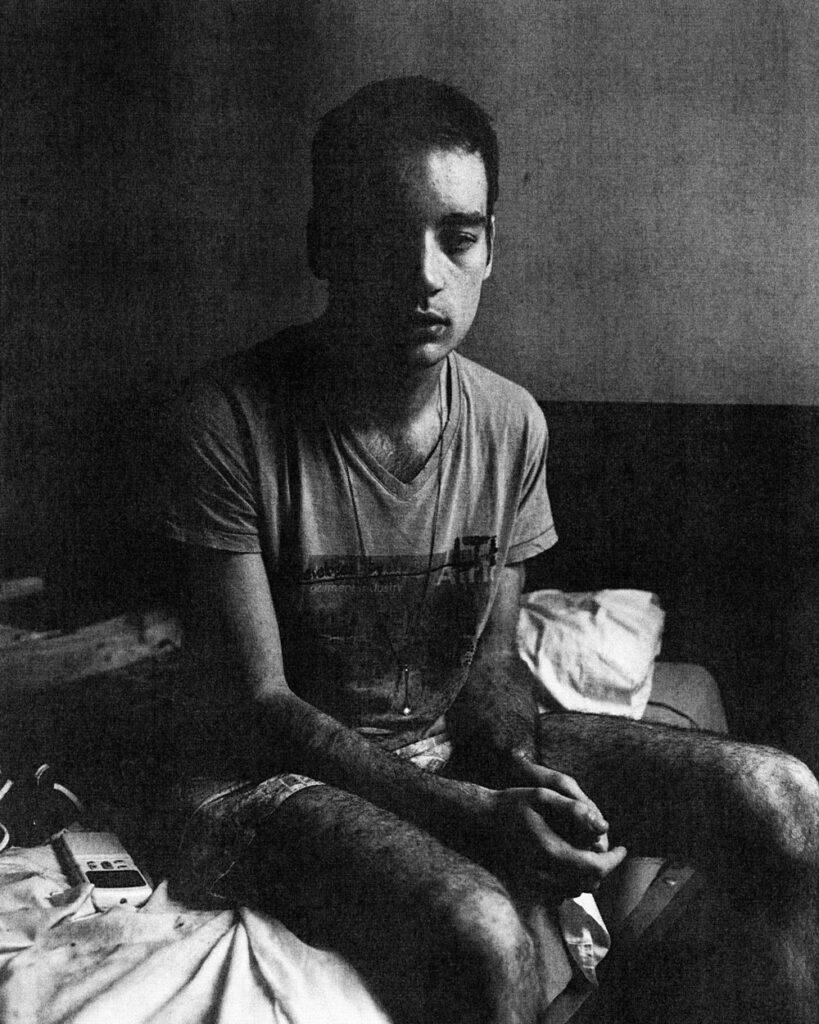

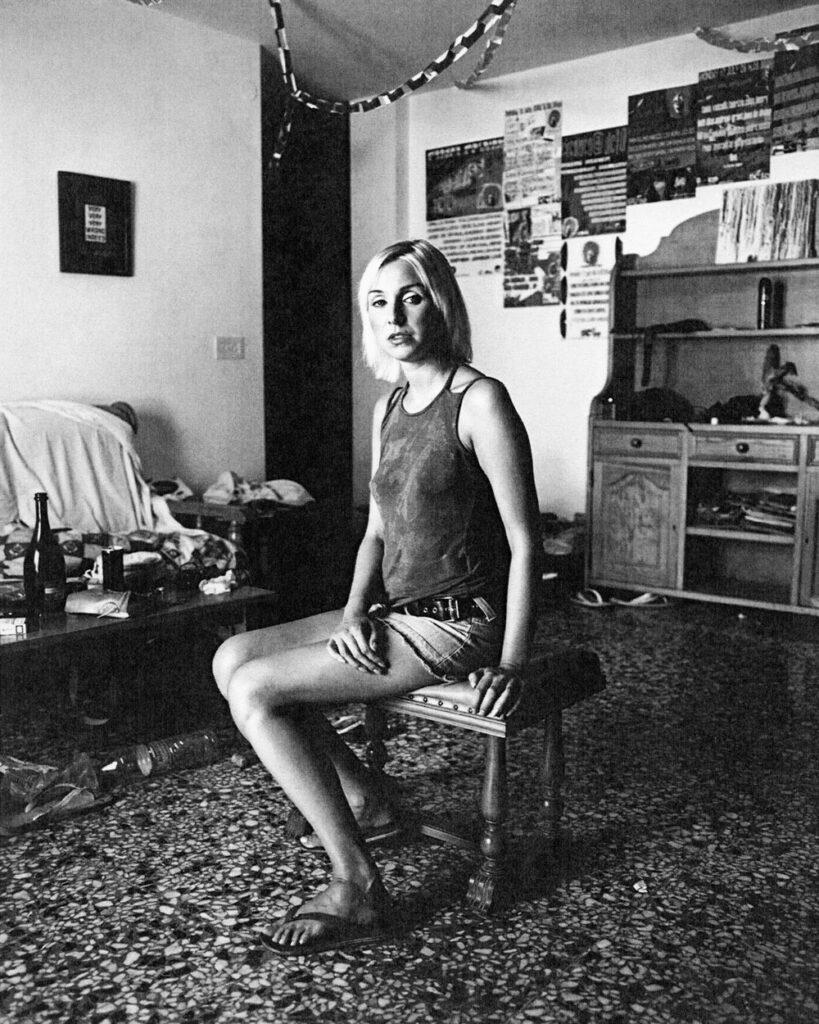

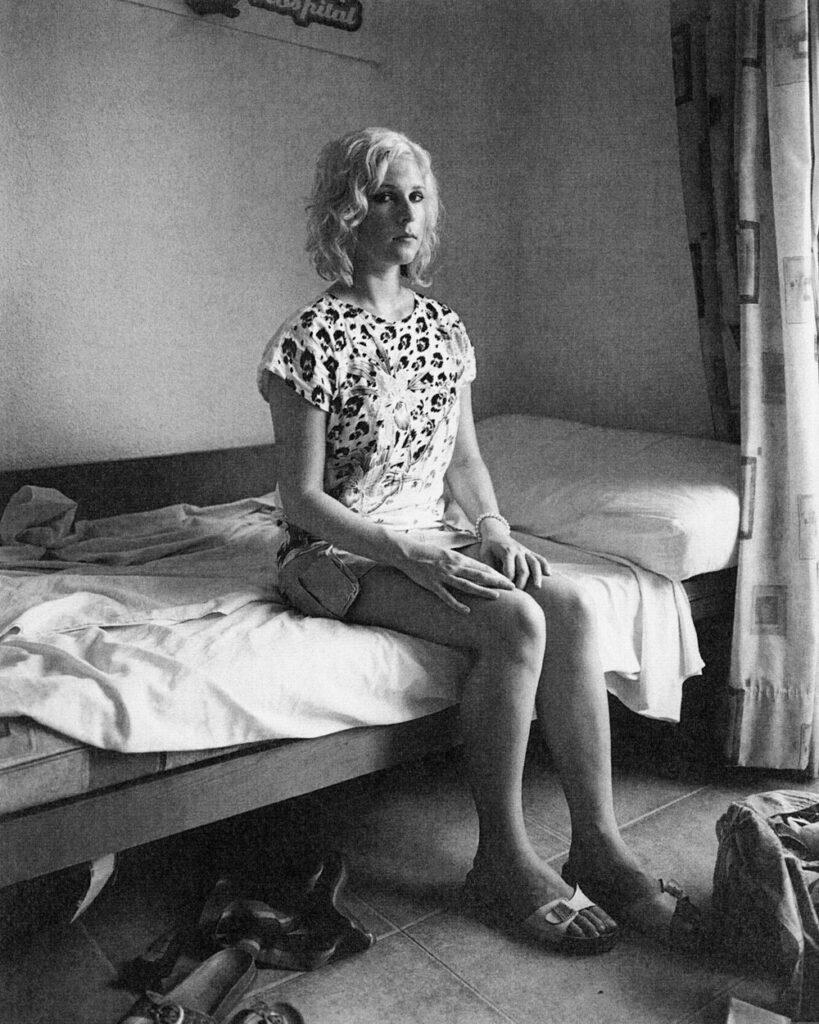

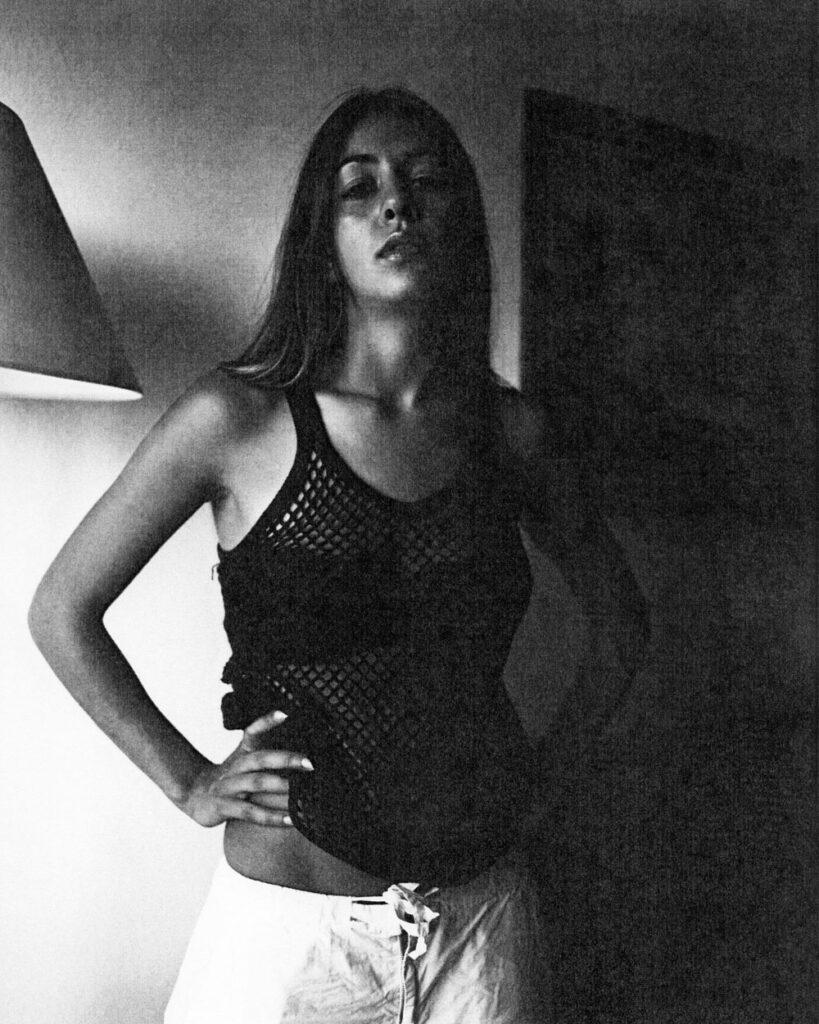

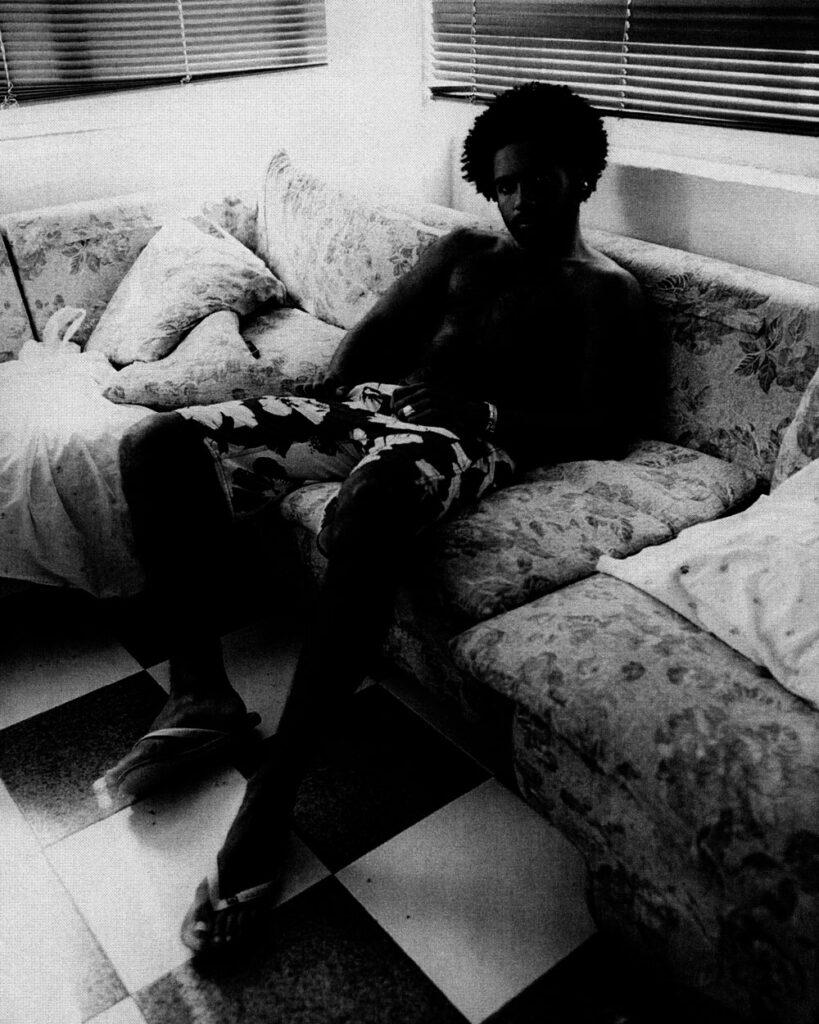

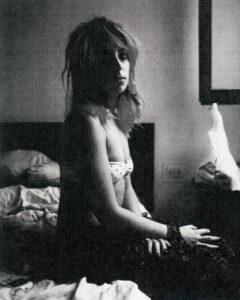

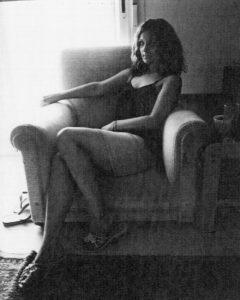

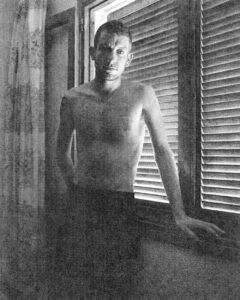

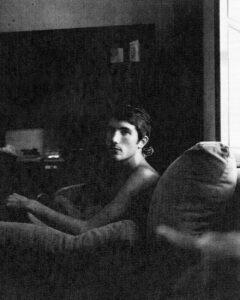

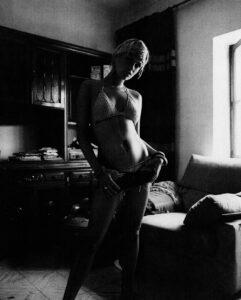

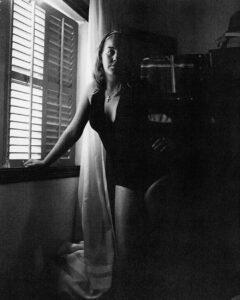

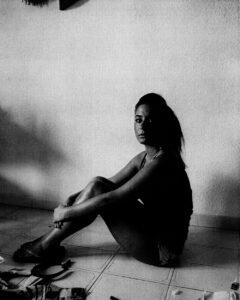

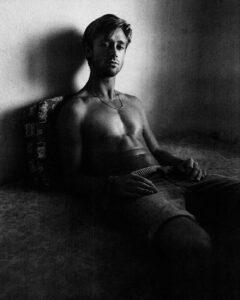

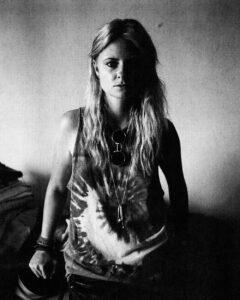

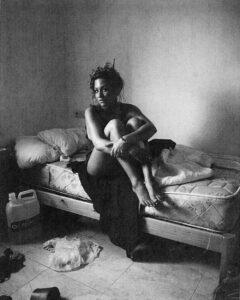

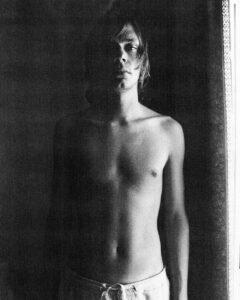

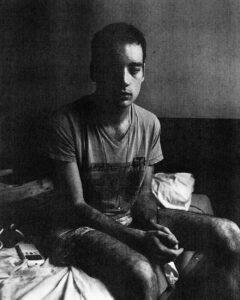

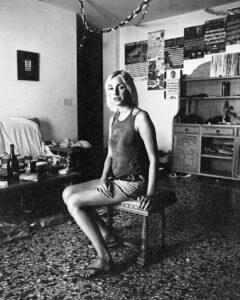

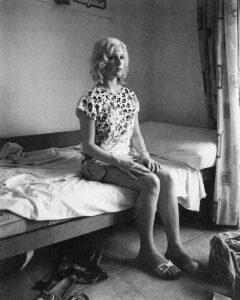

This search for the spirit of Ibiza, defined and redefined over decades of myth-making, still brings young initiates to the White Island for the first time every year. You can see it in the faces of the people photographed by Gareth McConnell; in their barren, functional rooms sparsely decorated with party posters and strewn with crumpled bedsheets, discarded clothing and the detritus of the previous night’s celebrations: their determination to endure privation in search of the dream.

Some of them come for a week, some for two; others try to stretch out their pleasures over a seemingly endless ‘summer of love’, taking ill-paid work promoting clubs and bars or dealing drugs to their fellow Brits, just like the bright young doleites, football casuals, itinerant chancers and criminal entrepreneurs who formed the original British E crowd back in 1987 when Paul Oakenfold and his friends flew in. Not all of them last out the season; not all of them go home friends. Sometimes the money runs out, drug deals go wrong, relationships splinter as chemical derangement bends the consciousness out of shape, hired motorbikes crash, like the one that killed Velvet Underground singer Nico on the island in 1988. Others return, year after year for decades, a few even choosing to make their home there, leaving the northern European drizzle and chill behind them. The sun-dappled Balearic Beat, meanwhile, has become a musical genre with a life of its own, independent of the island itself.

Clubbing is not, of course, Ibiza’s only reality. Many of the island’s 130,000 inhabitants never visit places like Amnesia or Privilege and do not care to do so. And even the nightlife tourists don’t all come for the Ecstatic highs: some British holidaymakers still prefer the more traditional pleasures of sun, sand, superlager and the chance of a bit of drunken sex, congregating in their raucous masses in the glitzy ghetto of San Antonio’s West End, the scene documented for the alcopops-and-pills generation in the reality-TV series Ibiza Uncovered, which focused on the boozy antics and amorous blunderings of Brits on their annual pilgrimage to foreign shores: the world-within-a-world where Amnesia just means something you wake up with the morning after the night before.

Ibiza has often been mythologised in film as a decadent idyll – but strangely, not always in a positive way. More, with its ‘beautiful people’ losing their minds to heroin, is an elegy for the death of the 1960s hippie dream, while Michael Dowse’s 2005 film It’s All Gone Pete Tong, which chronicles the decline of a cocaine-addled celebrity DJ, could be seen as an end-of-era film for the money-crazed ‘superclub’ era of the 1990s that saw the beatific visions of acid house torn apart in a savage, drug-debilitated, materialistic frenzy.

But few films have ever really managed to capture that intangible Ibiza spirit. Even a ravers’-favourite documentary from 1990, A Short Film About Chilling, was undermined by the inability of many people who spoke on camera to fully explain the island’s magic, and signed off with the vaguest of banalities: “It’s just a really wonderful feeling…” Tourists offering their wisdoms to documentary-makers have failed to come close either: “Everyone’s buzzing, everyone’s loving it,” one clubber told a BBC radio programme called ‘Britain’s Balearic Soul’: accurate perhaps, but somewhat lacking poetic inspiration.

And yet somehow that spirit (or the idea of that spirit) cannot be extinguished, however hard it is to explain in words. For me, it was the twisted early-afternoon peaks on the terrace at Space where everyone seemed to be locked into the same chemically-enhanced harmonic groove, or watching in wonder as the righteously blasted Happy Mondays turned Ku into a riot of freaky dancing, or seeing the sun go down on the beach outside Café del Mar for the first time, lost in reveries about the endless possibilities of the long night’s journey into dawn. For others it might be Manumission’s erotically-charged extravaganzas at Privilege, or the mayhem of DC10, or the more luxurious pleasures of Ibiza Town, of lavish villas and opulent restaurants, the secluded beach bars far from the holiday crowds, or a spiritual pilgrimage to the goddess Tanit’s shrine in a hilltop cave, or to meditate among the mystical carvings and rock-sculptures at the remote beach of Atlantis…

The Ibiza myth that has enchanted so many has been embellished over the years by a cast of colourful characters – by Freddie Mercury and Bad Jack Hand, Raoul Hausmann and Grace Jones, Errol Flynn and Danny Rampling, Wham! and Pink Floyd. But perhaps more importantly, it has been enhanced by all those nameless bohemians and artists and writers and hippies and ravers who have passed through and are still passing through; still contributing to what Ibiza is today, and to the myth that will bring others here in years to come.

Matthew Collin is the author of ‘Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House’ (Serpent’s Tail).