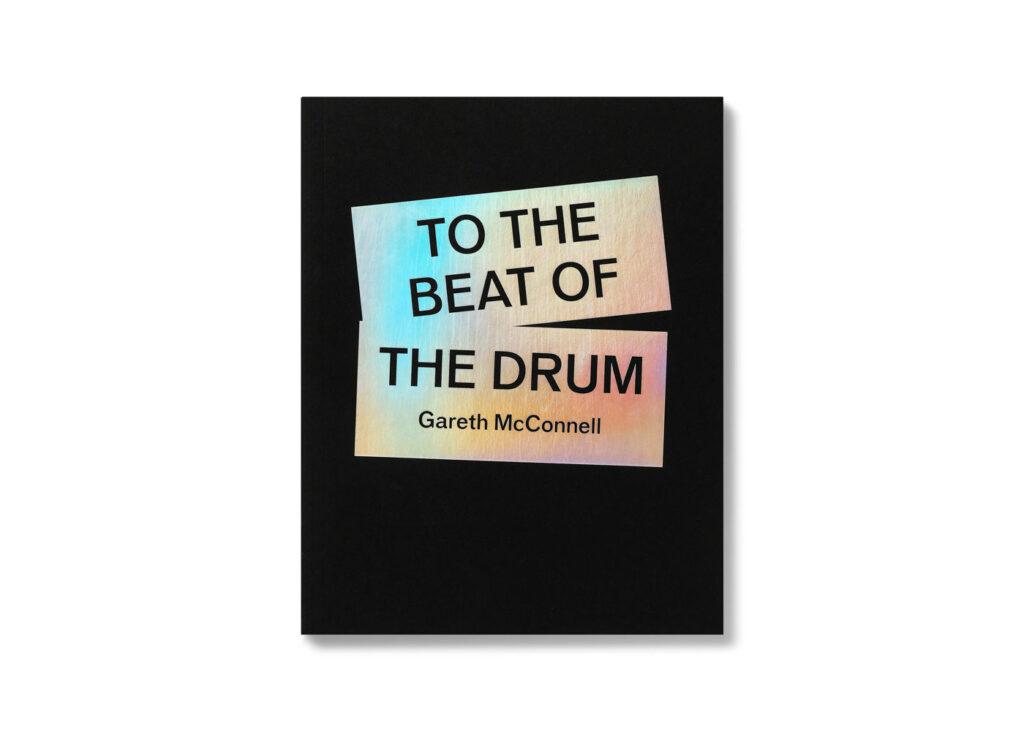

To The Beat Of The Drum, by Sean O’Hagan, feature writer for The Guardian and The Observer

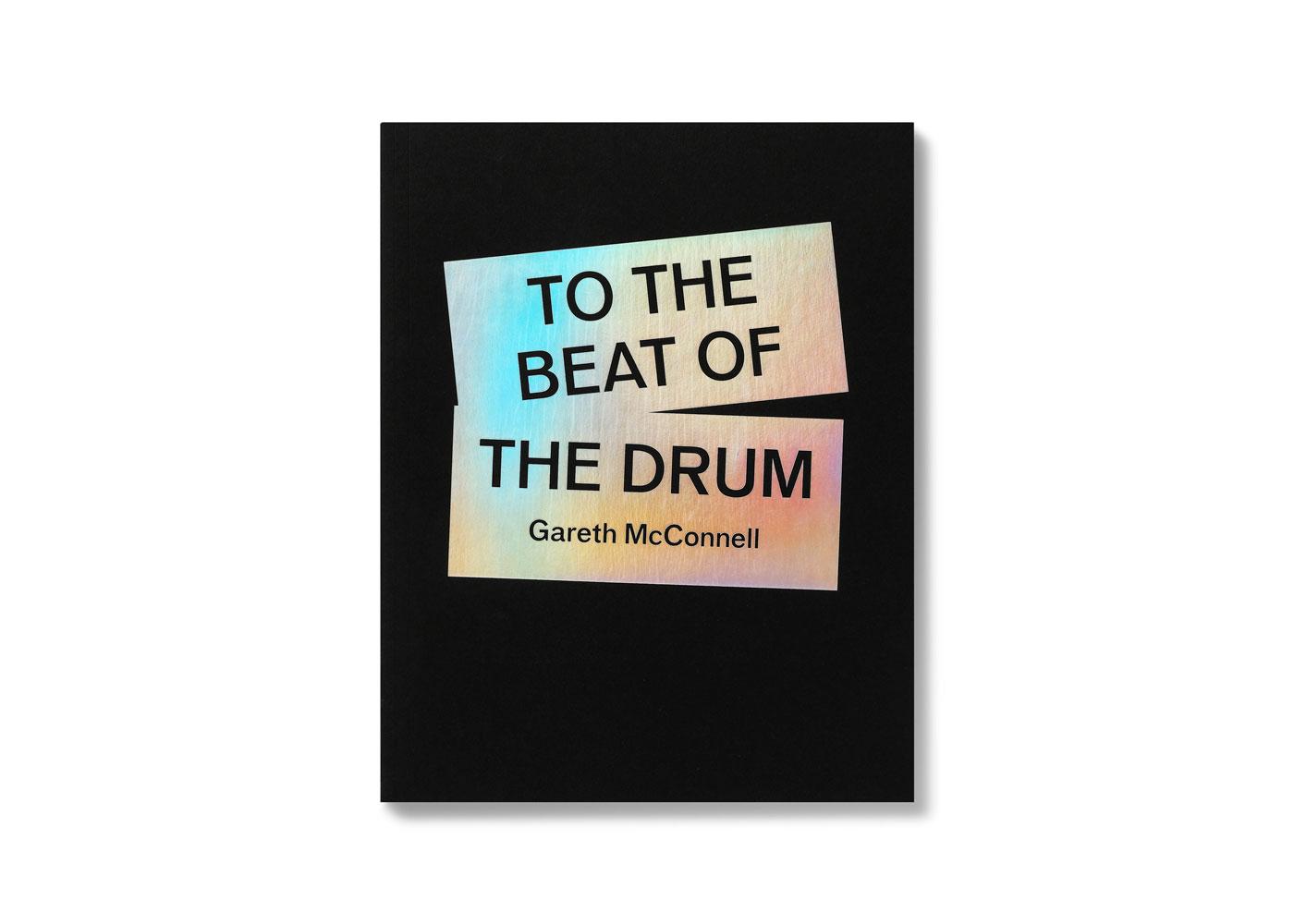

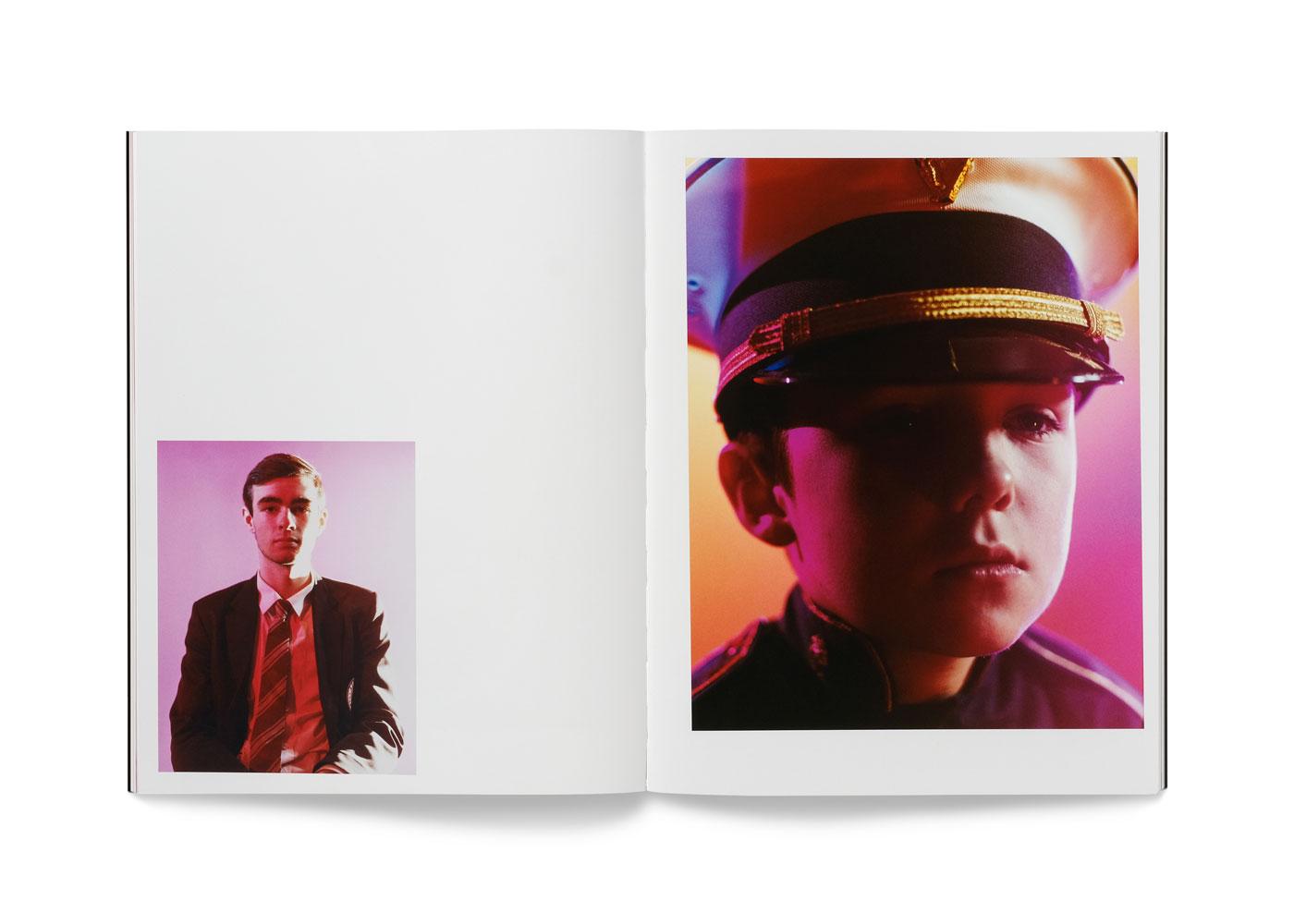

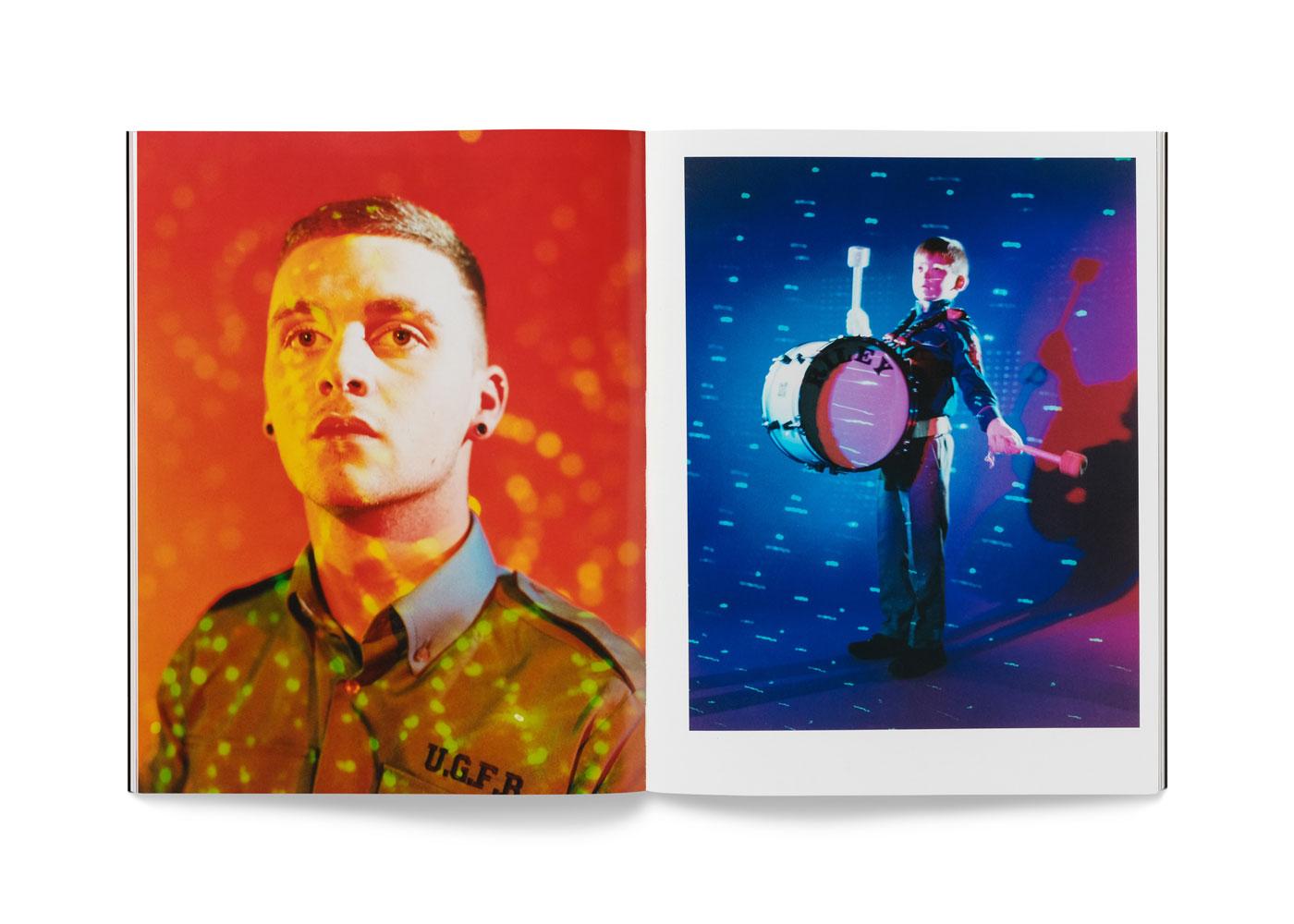

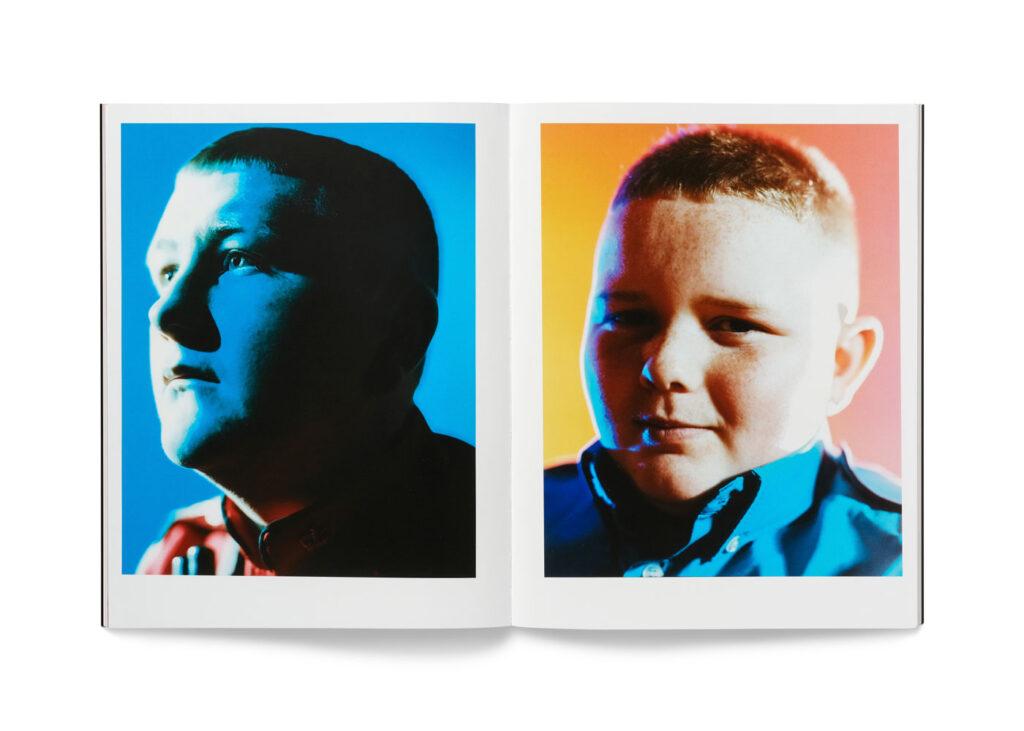

Towards the end of March 2021, the London-based photographer Gareth McConnell returned to Northern Ireland to shoot a series of portraits of young people in his home town, Carrickfergus, and nearby Larne. The portraits were commissioned by Intercomm, a Belfast-based cross-community project, and the subjects, aged between seven and 26, were members of local loyalist marching bands. McConnell’s primary aim, he says, was “to try and transcend the familiar depictions of young people from Protestant working-class communities by seeking to evoke the more primal instincts that underlie these rituals of belonging”.

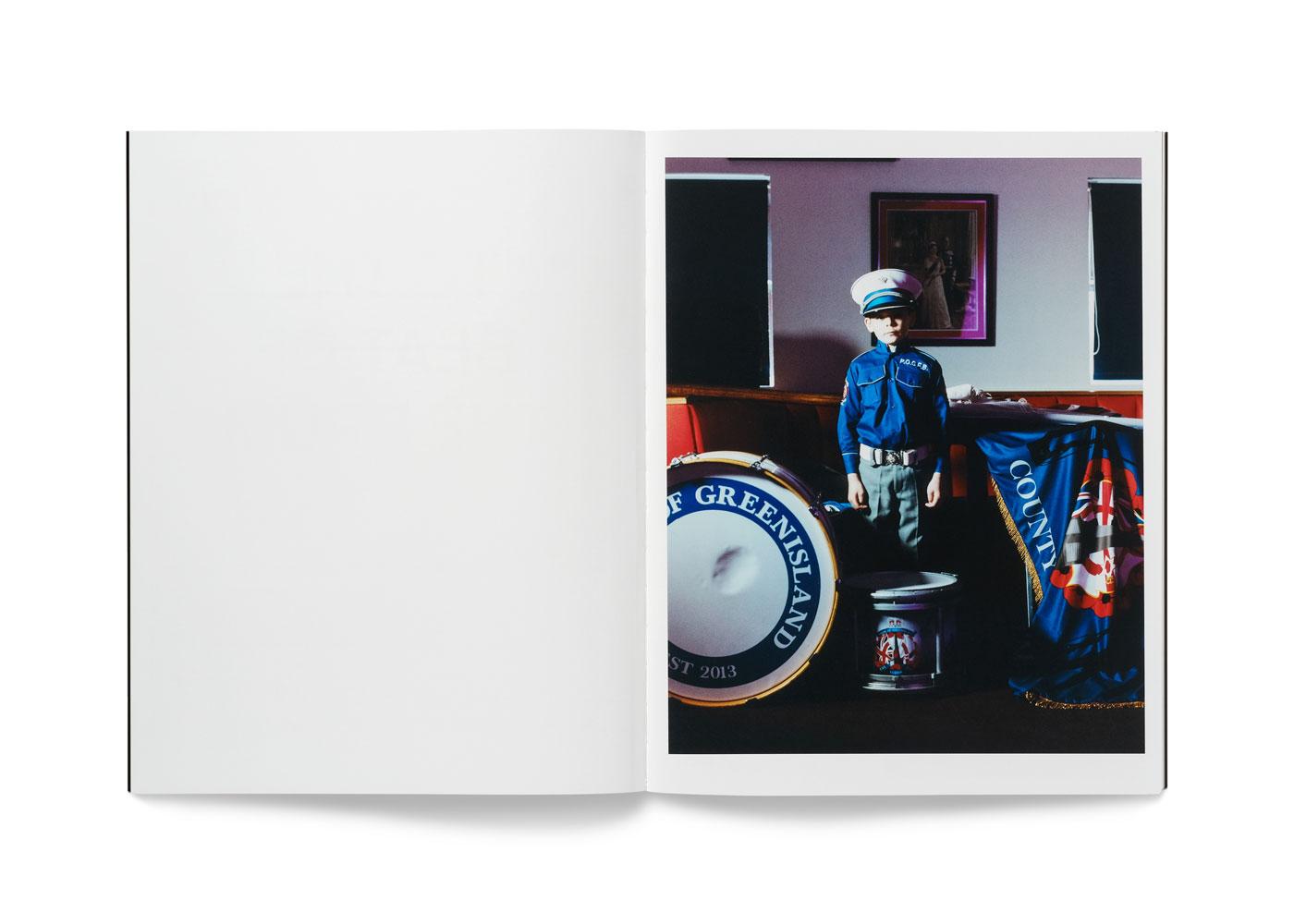

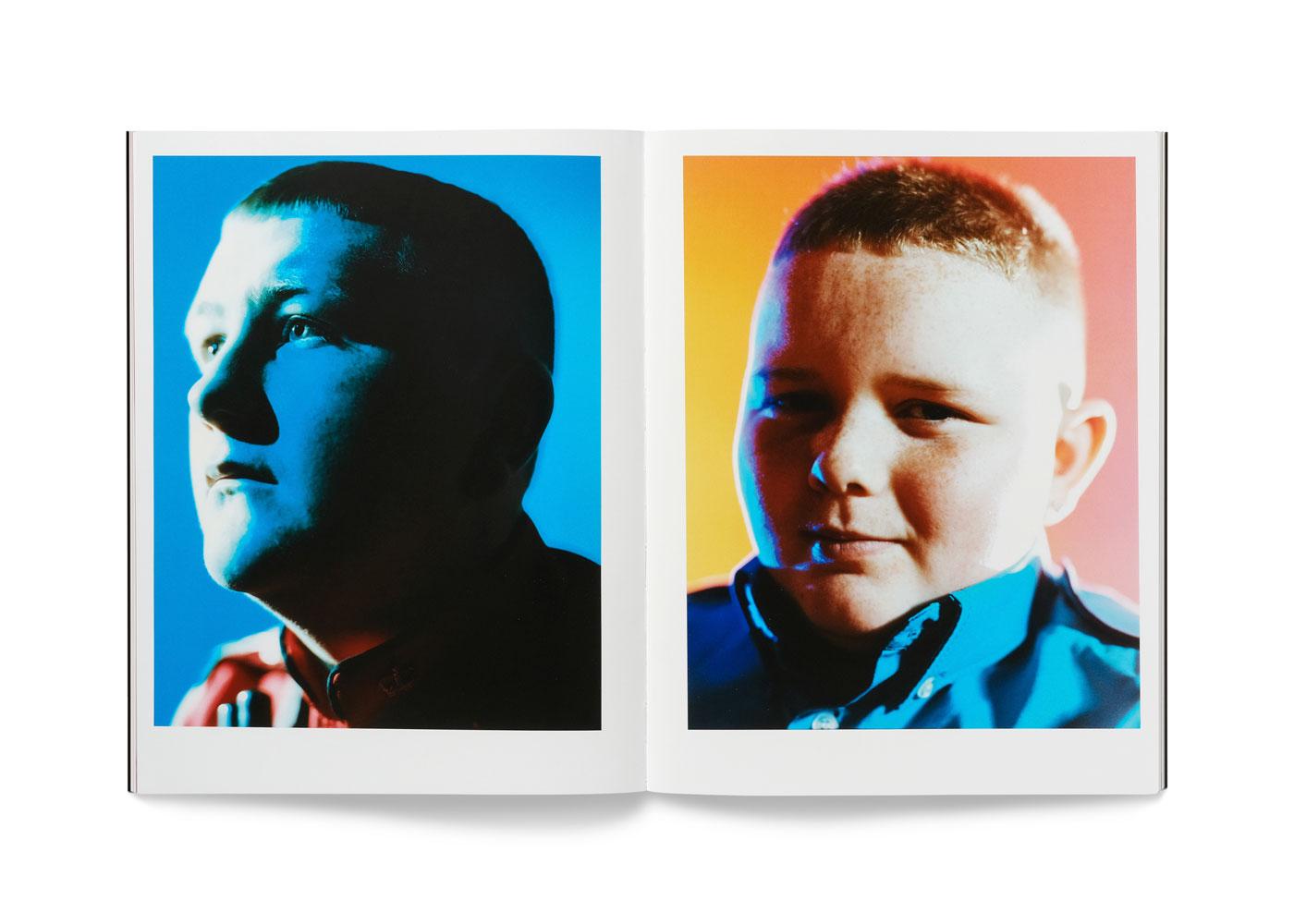

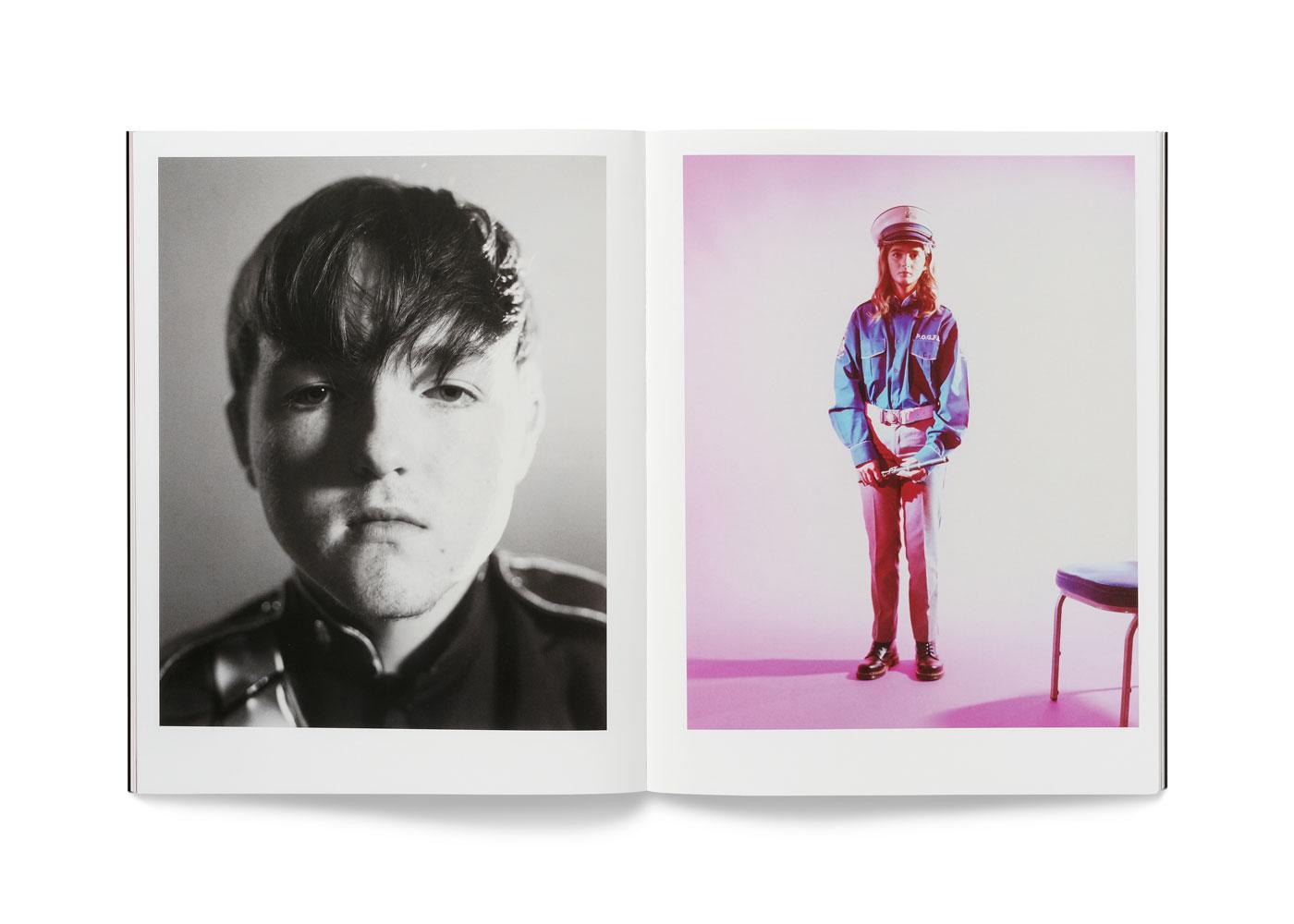

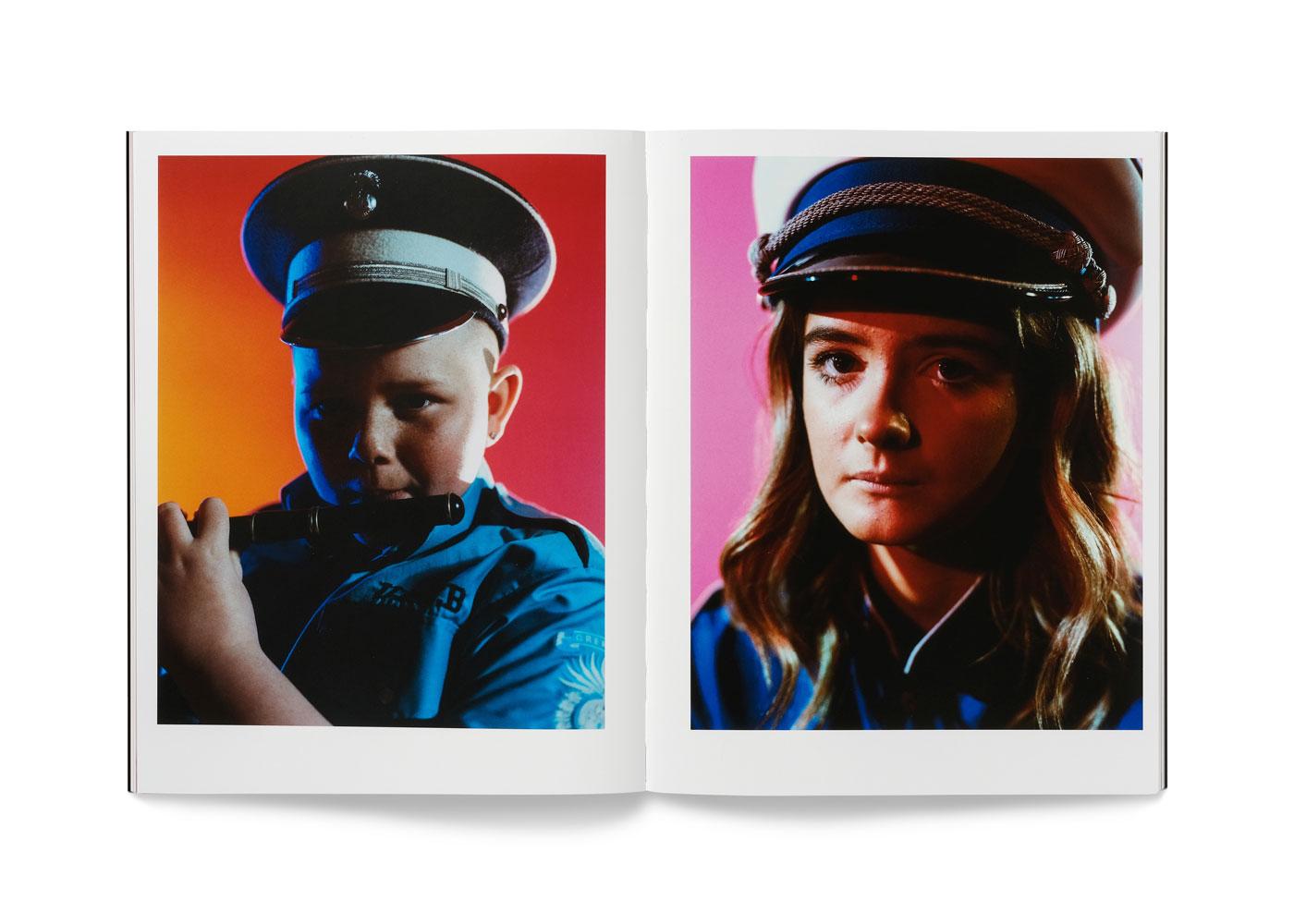

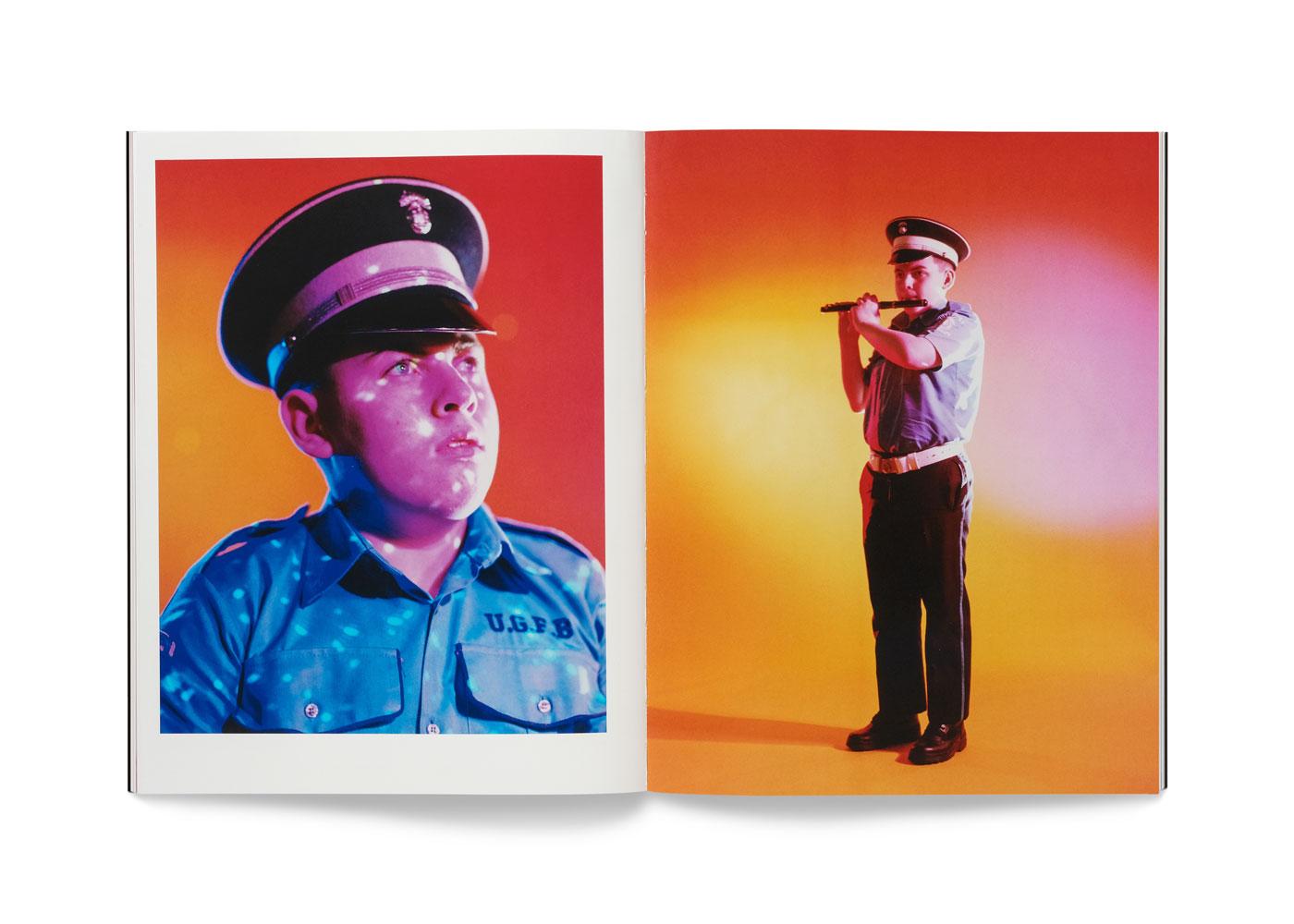

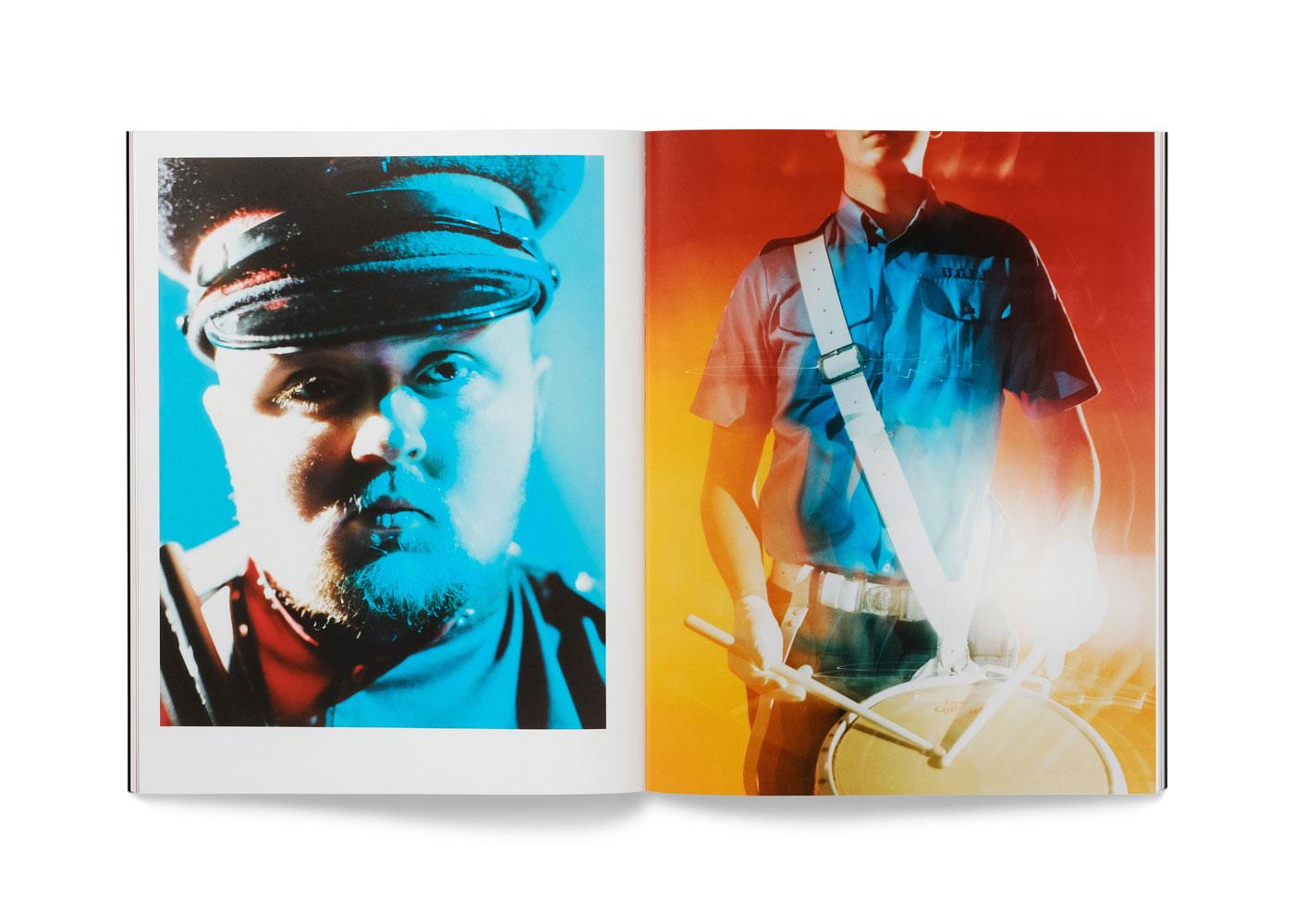

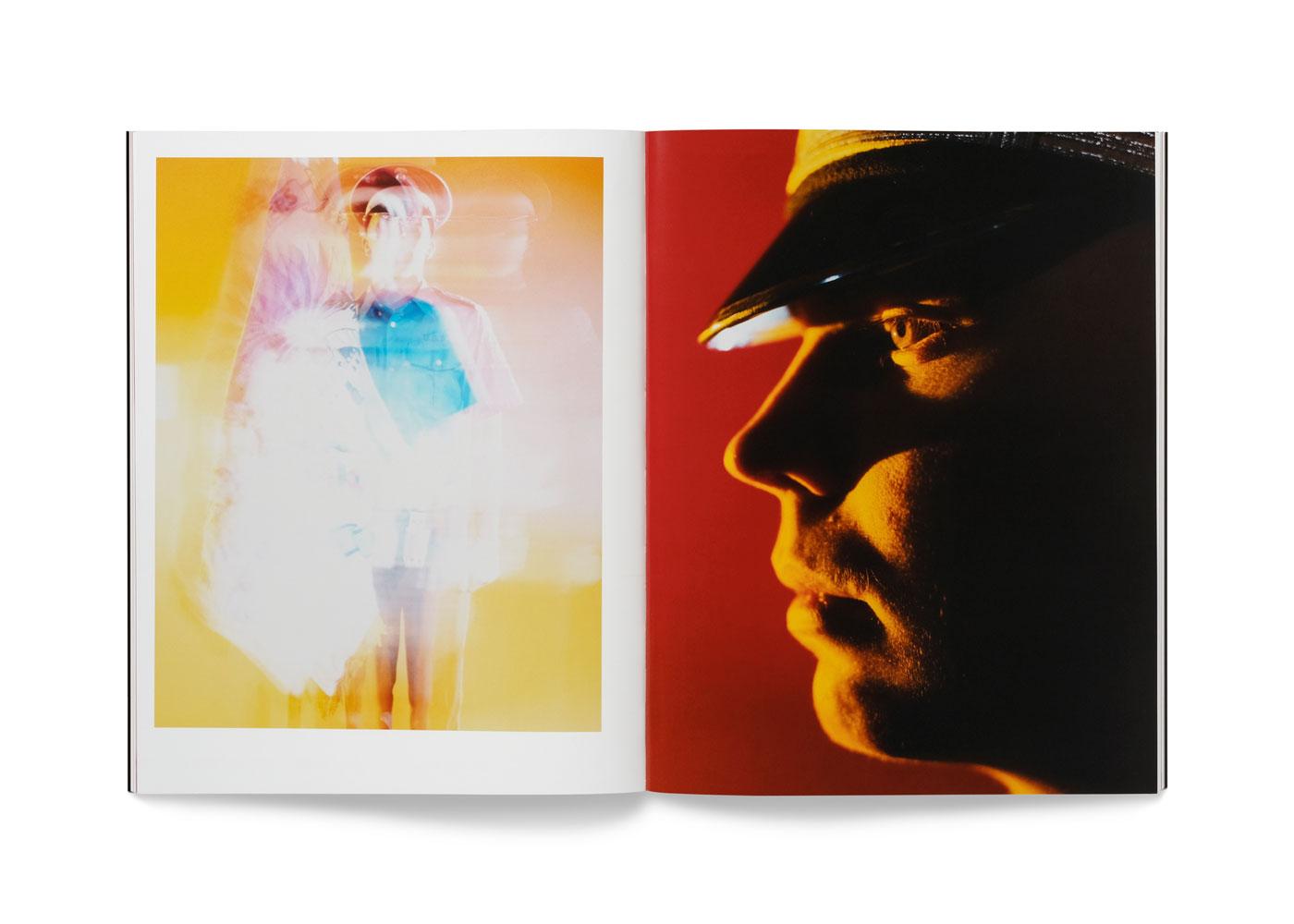

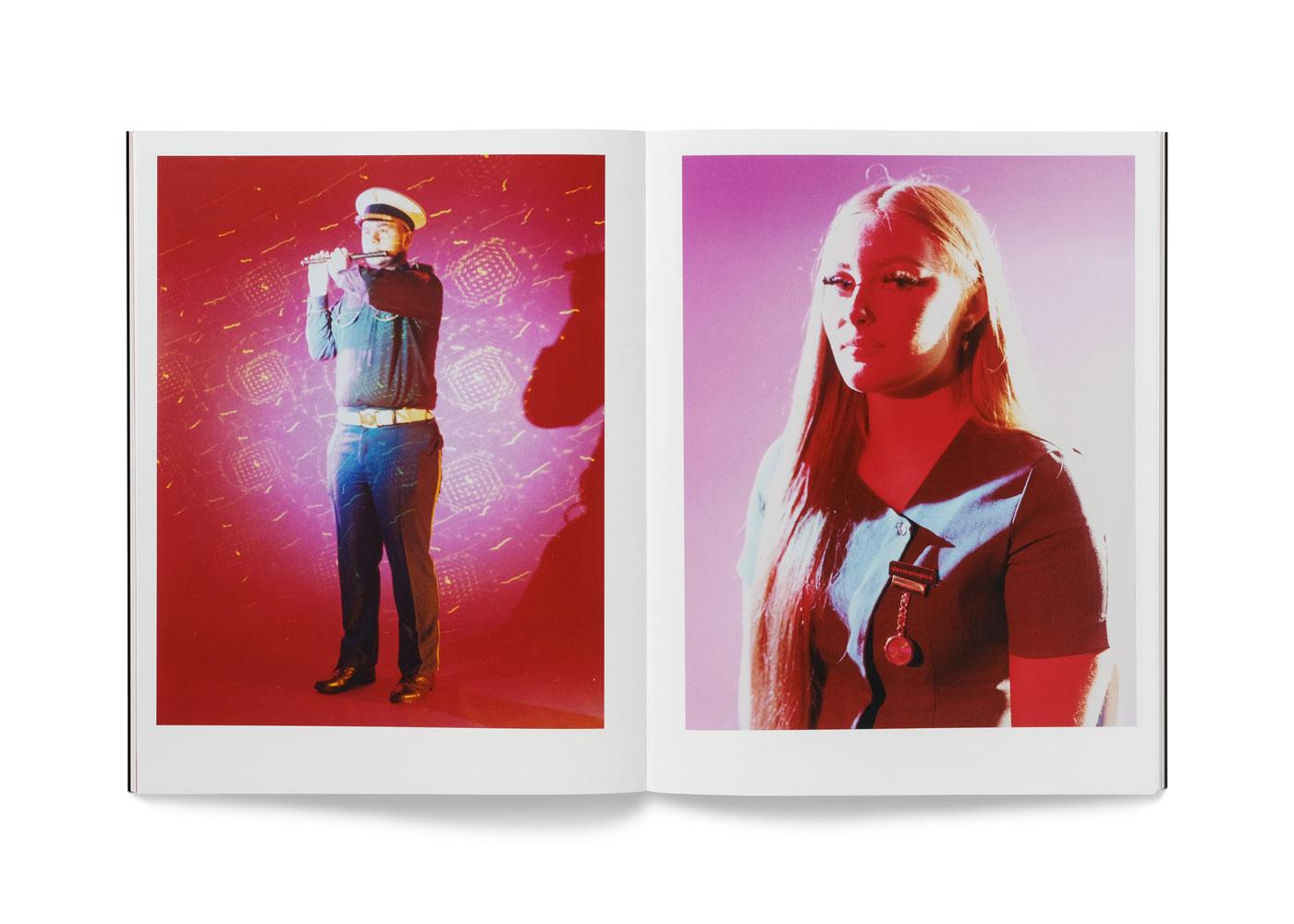

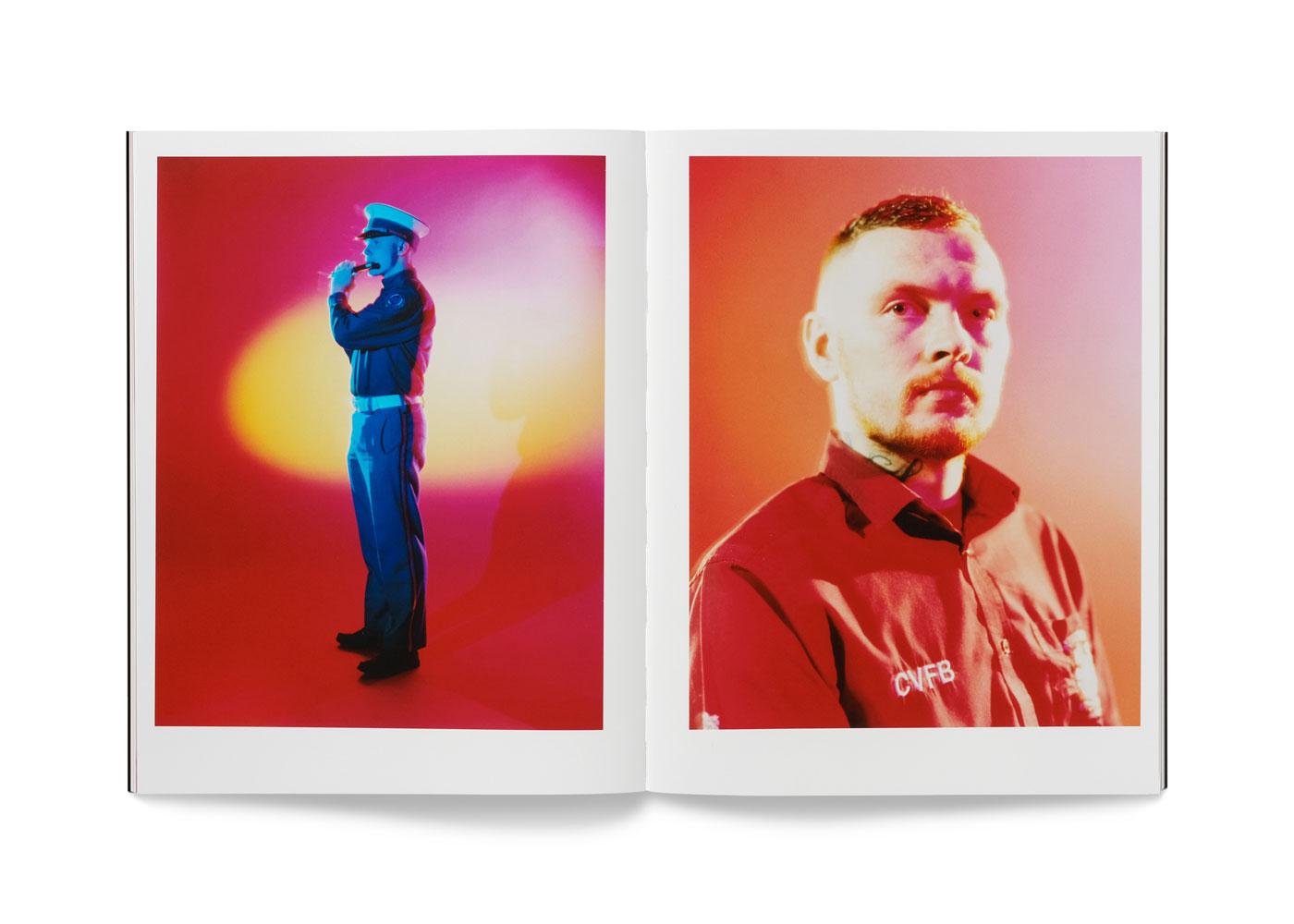

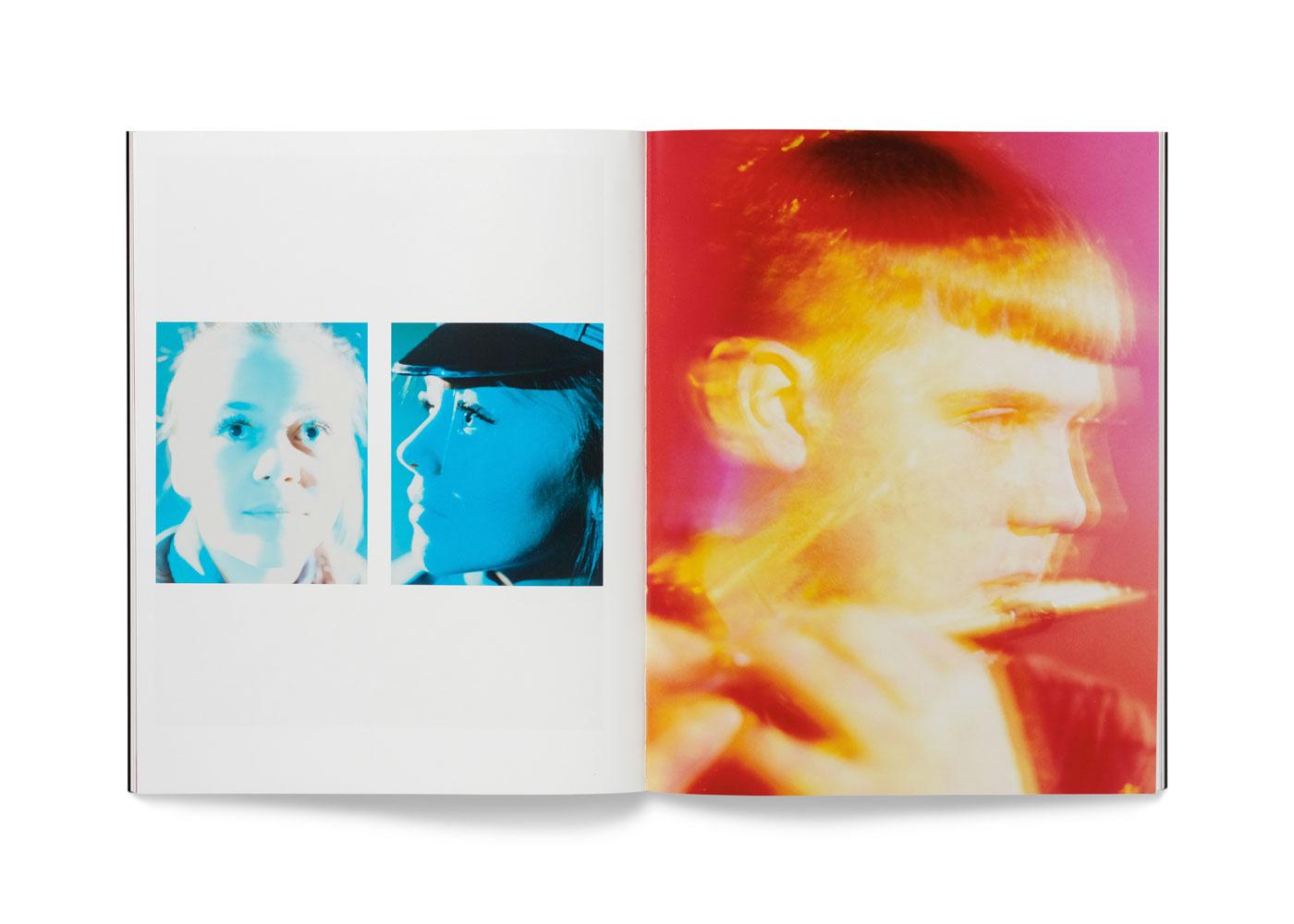

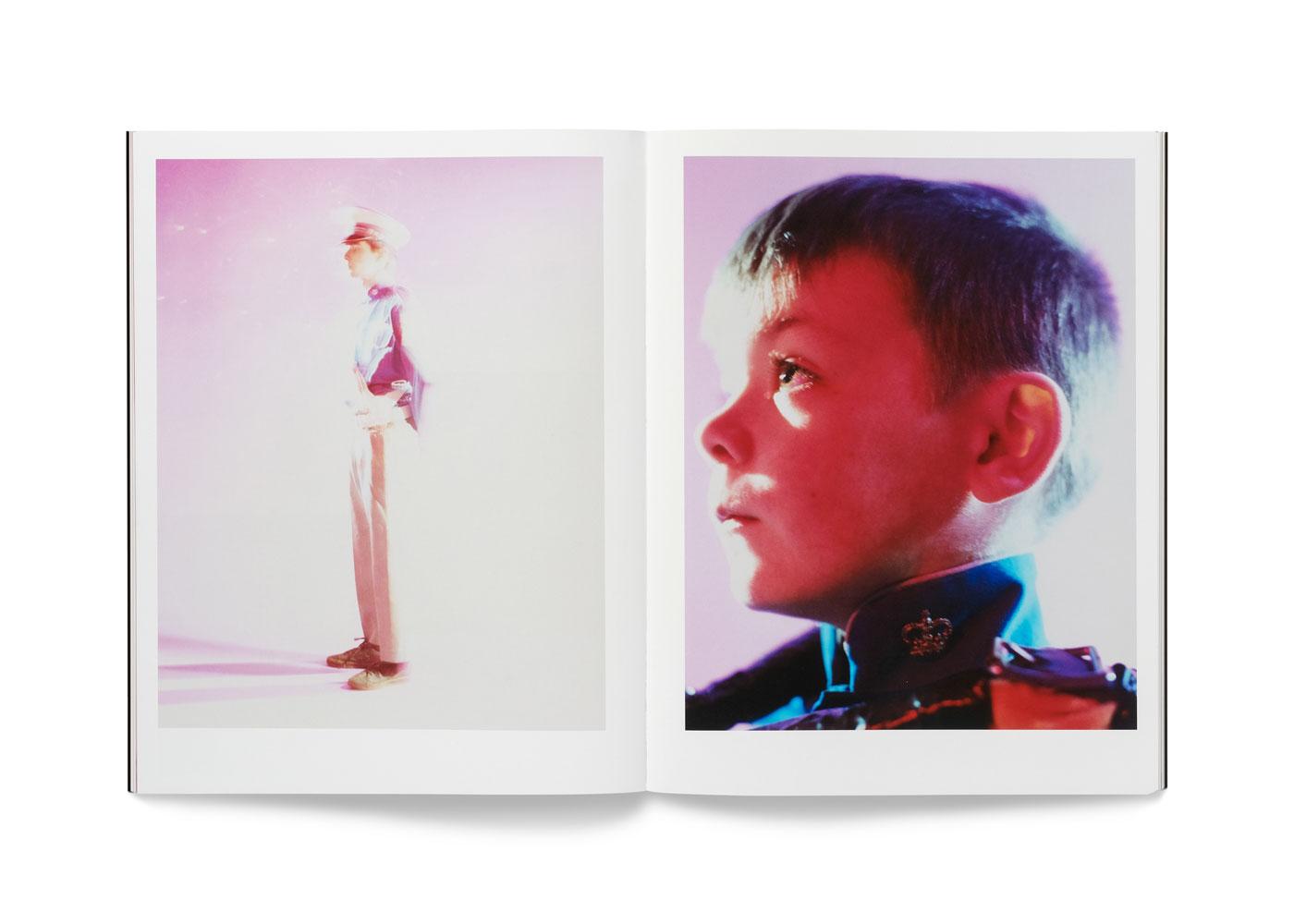

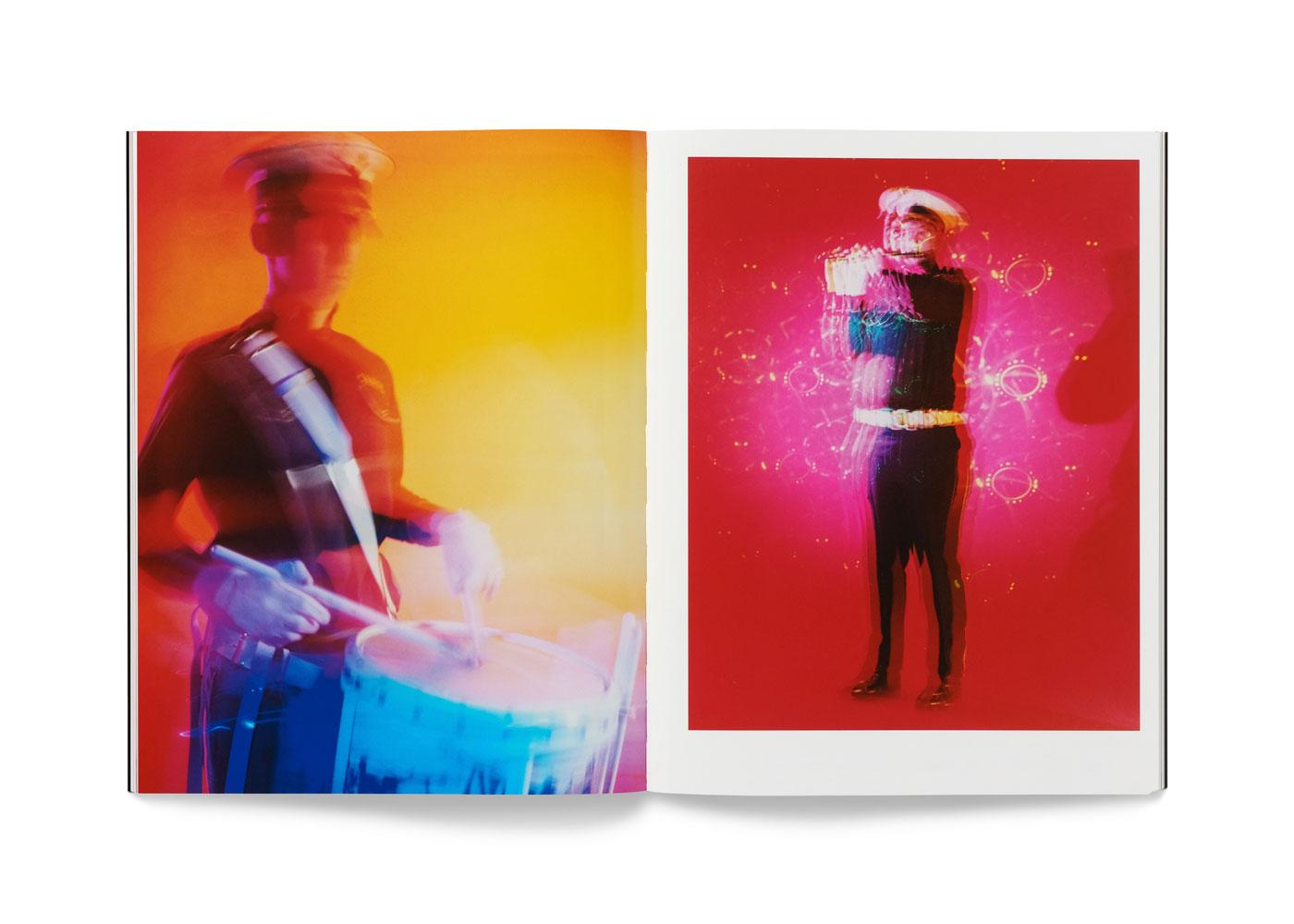

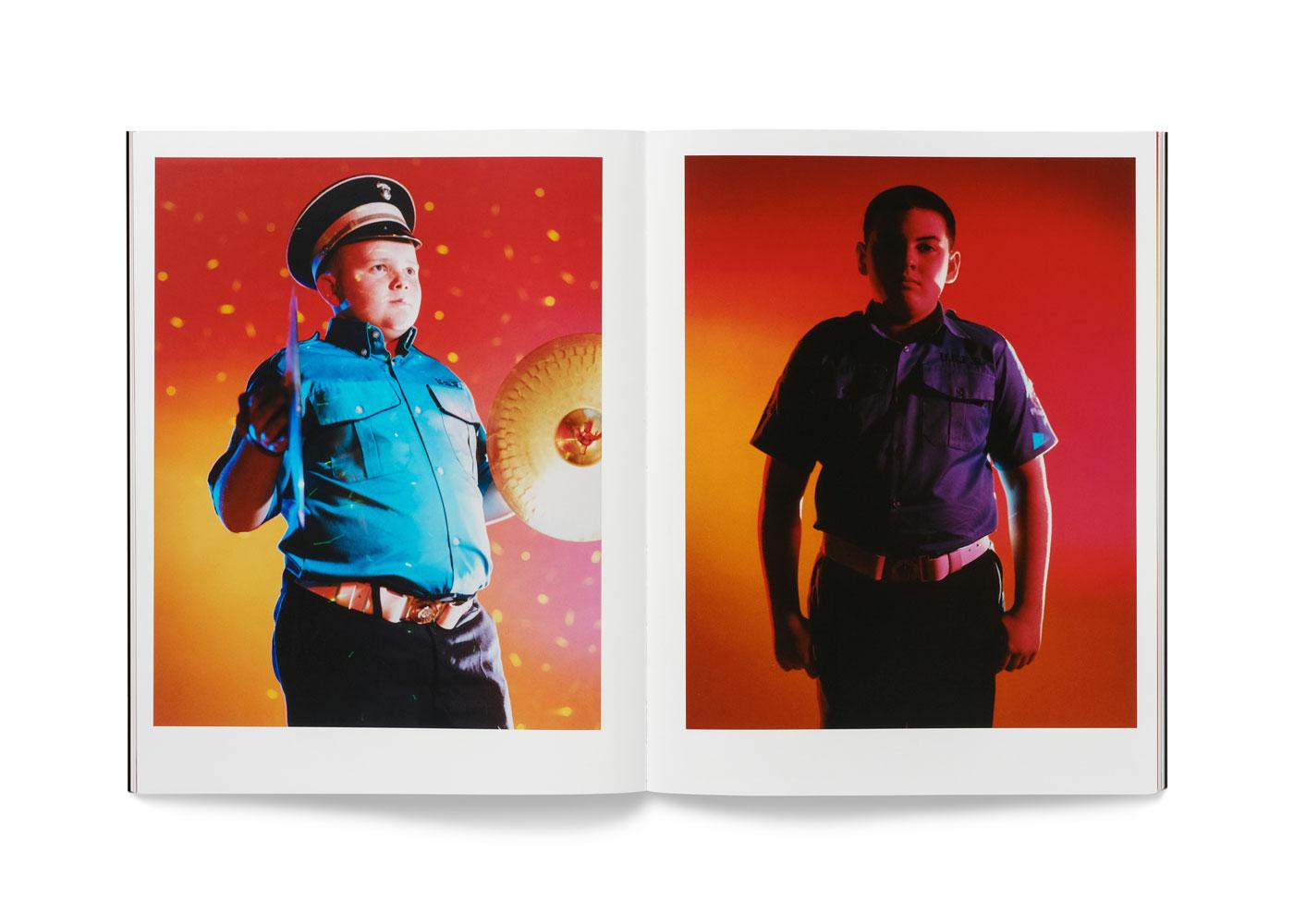

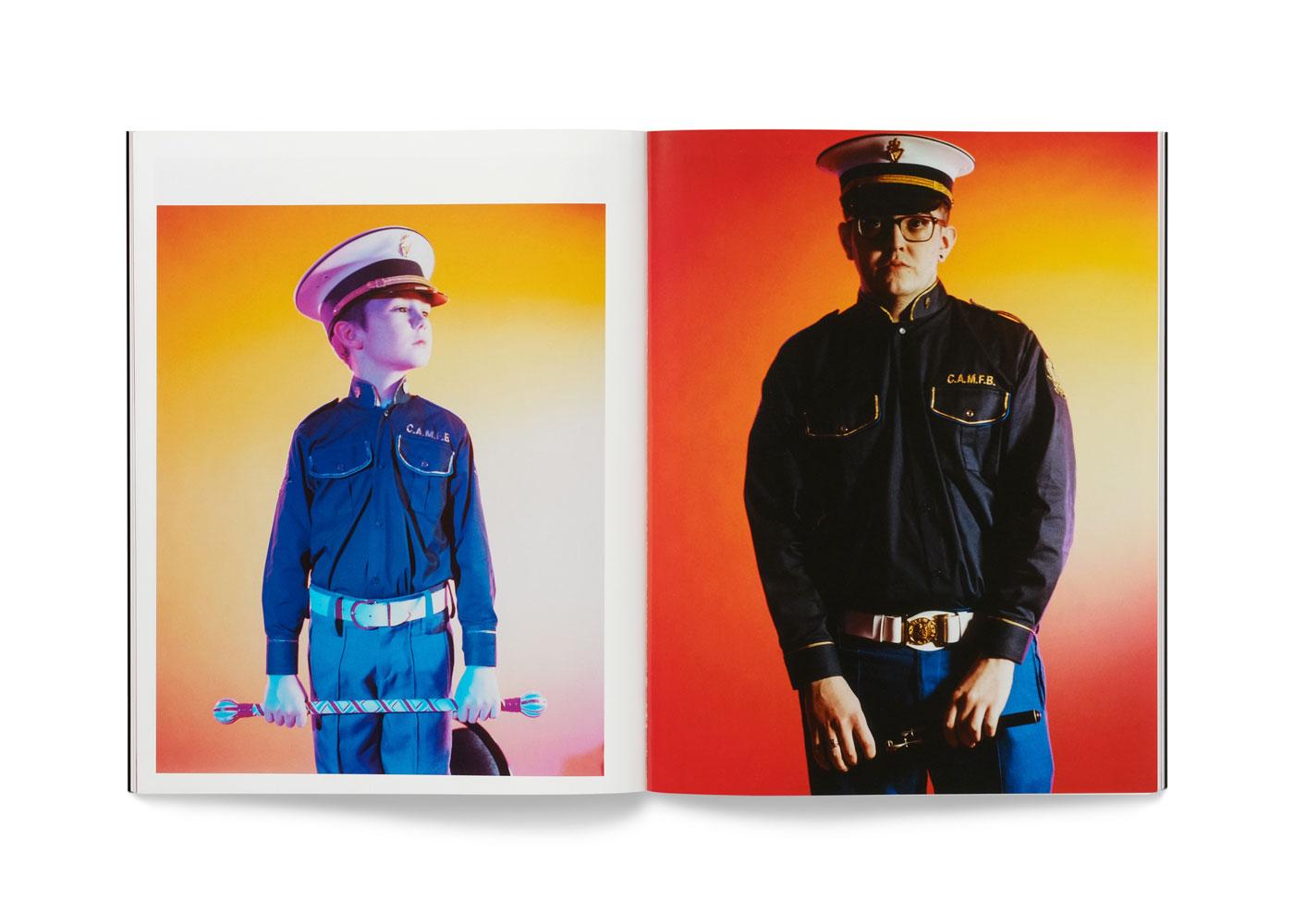

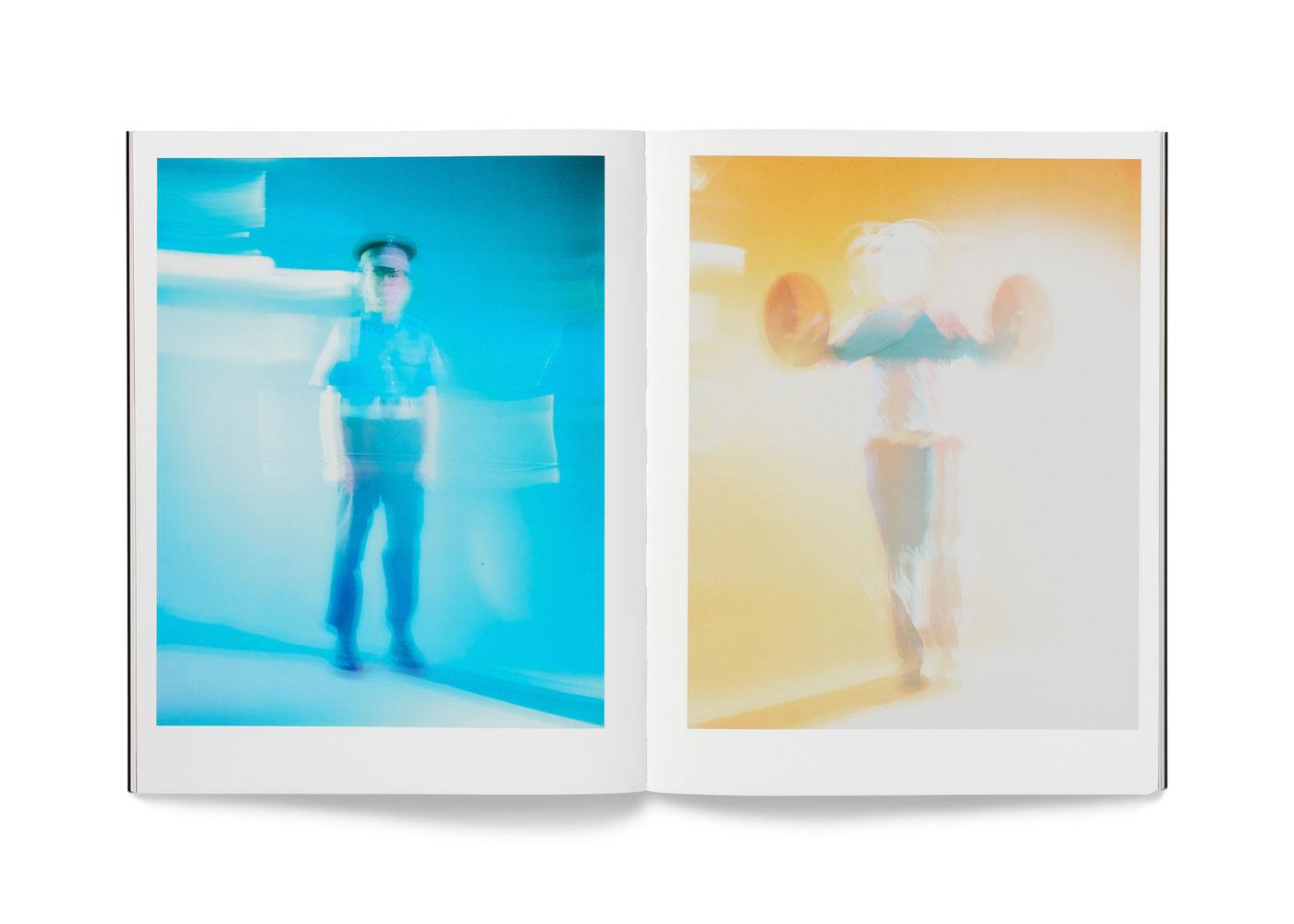

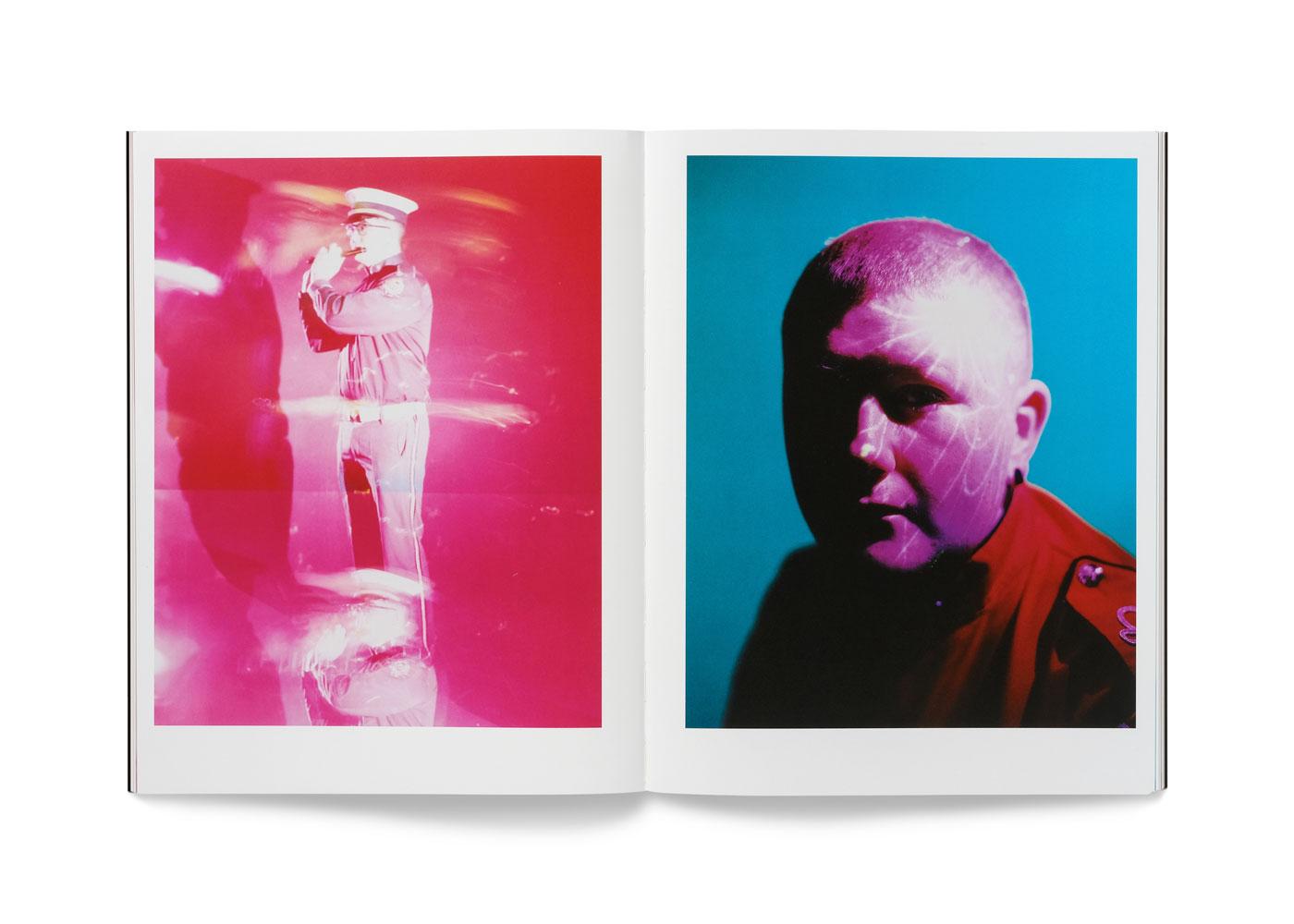

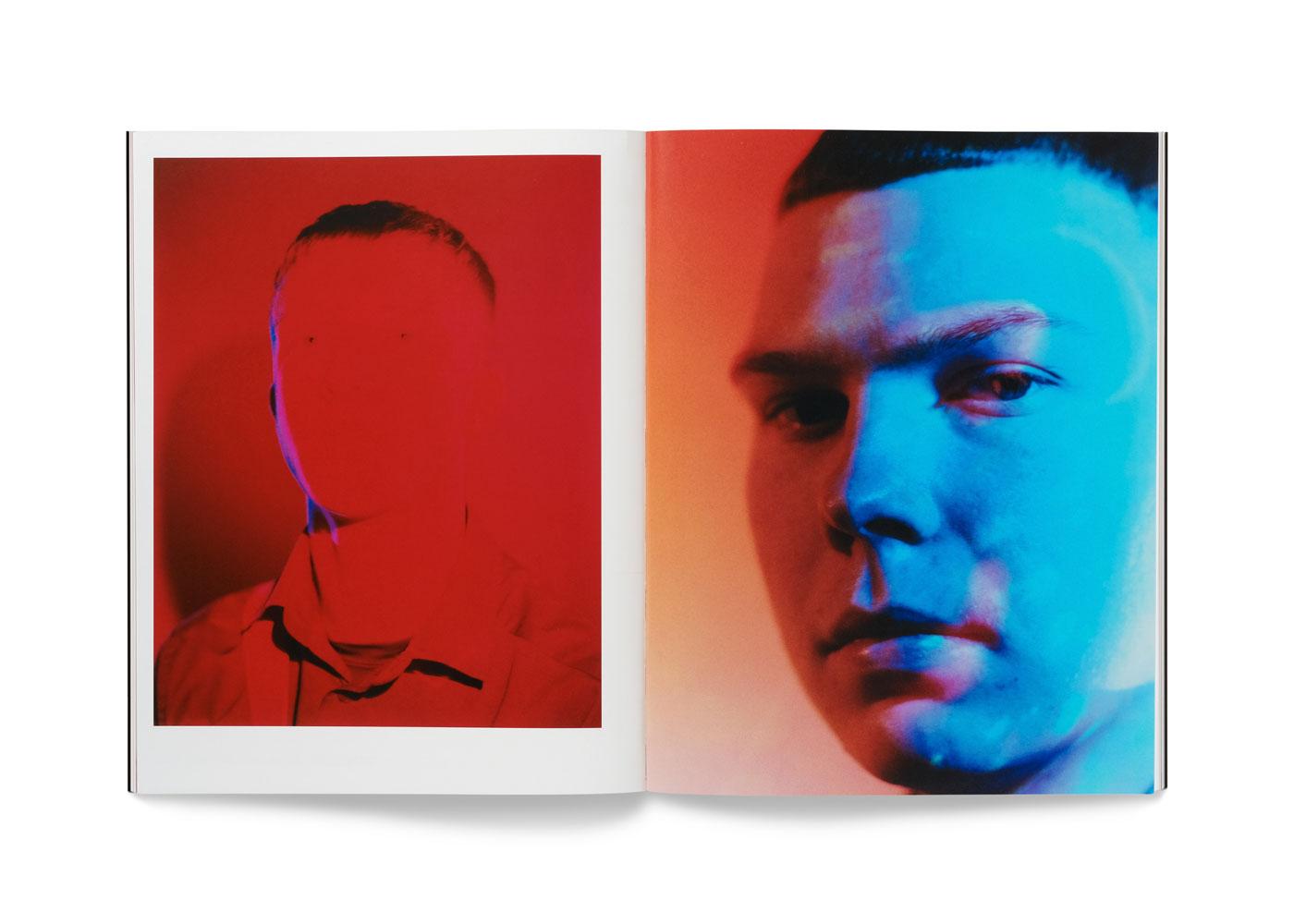

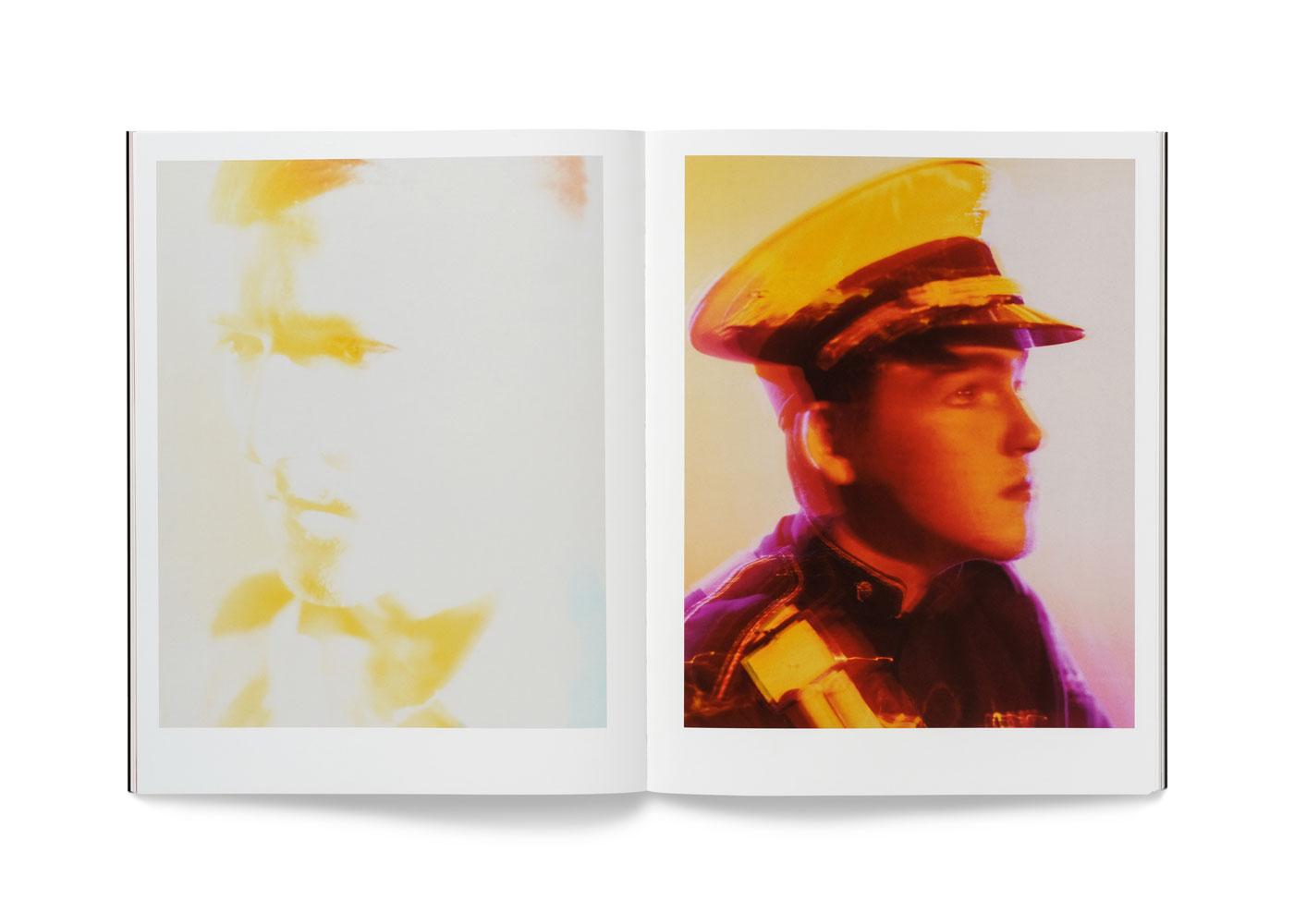

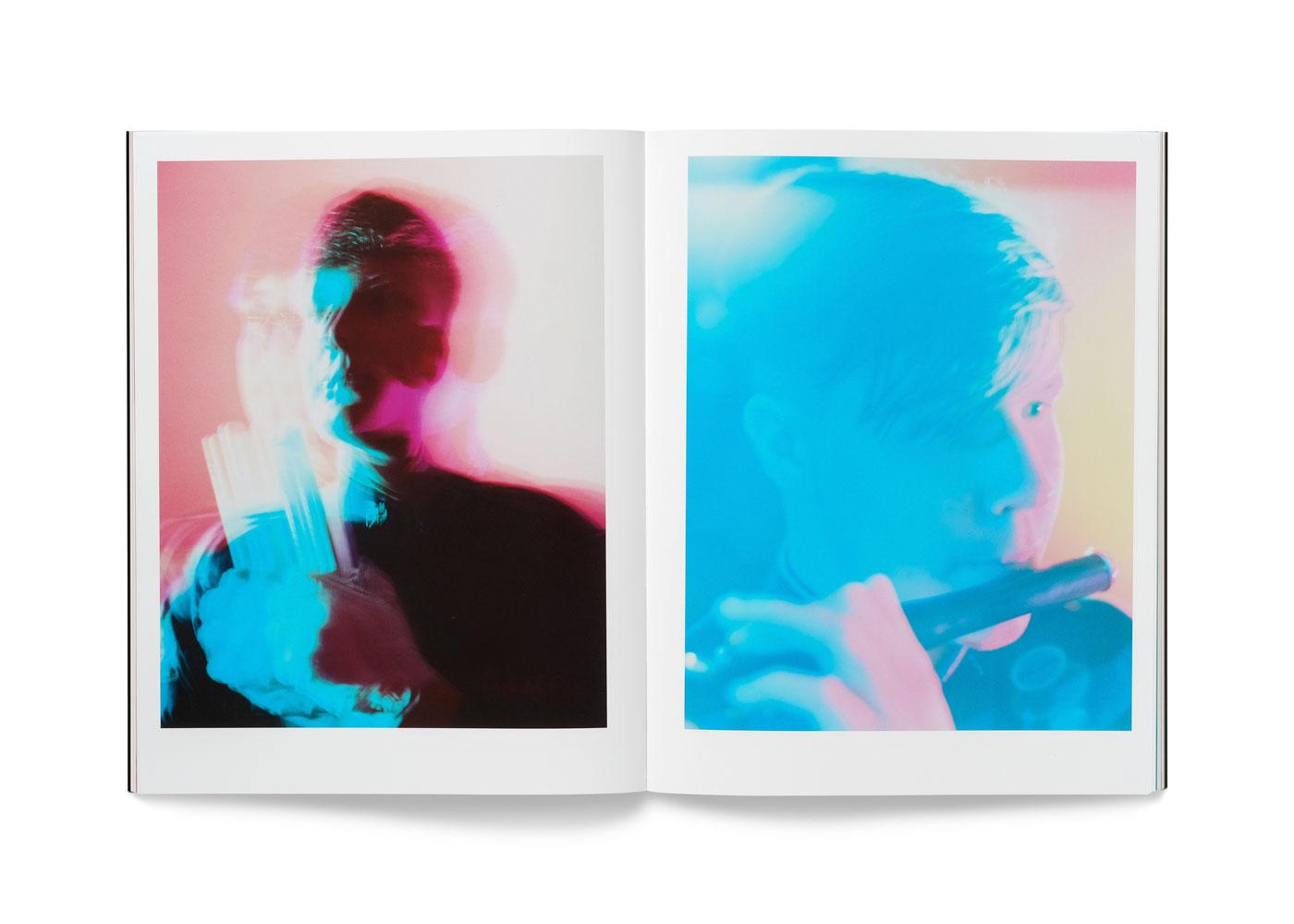

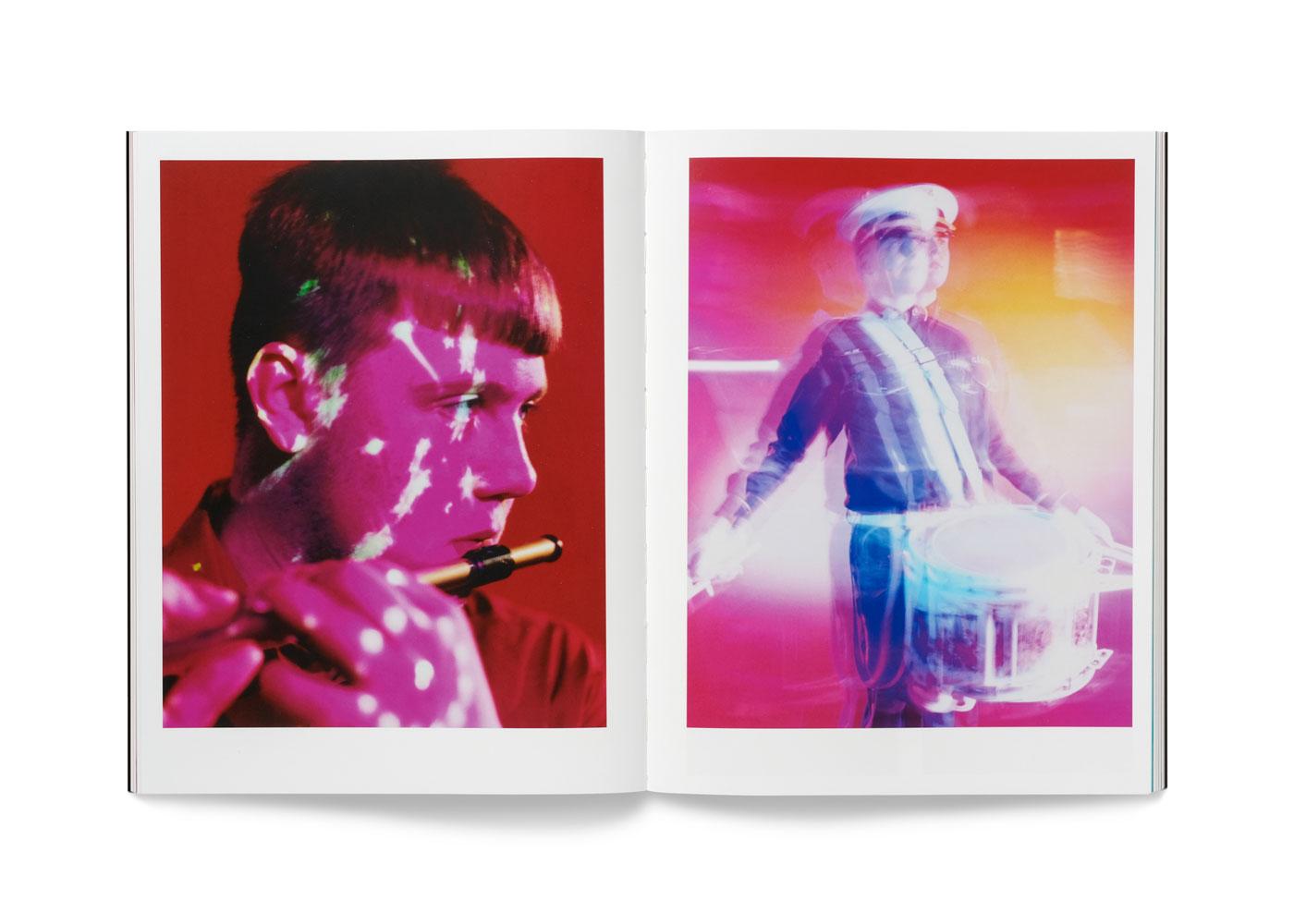

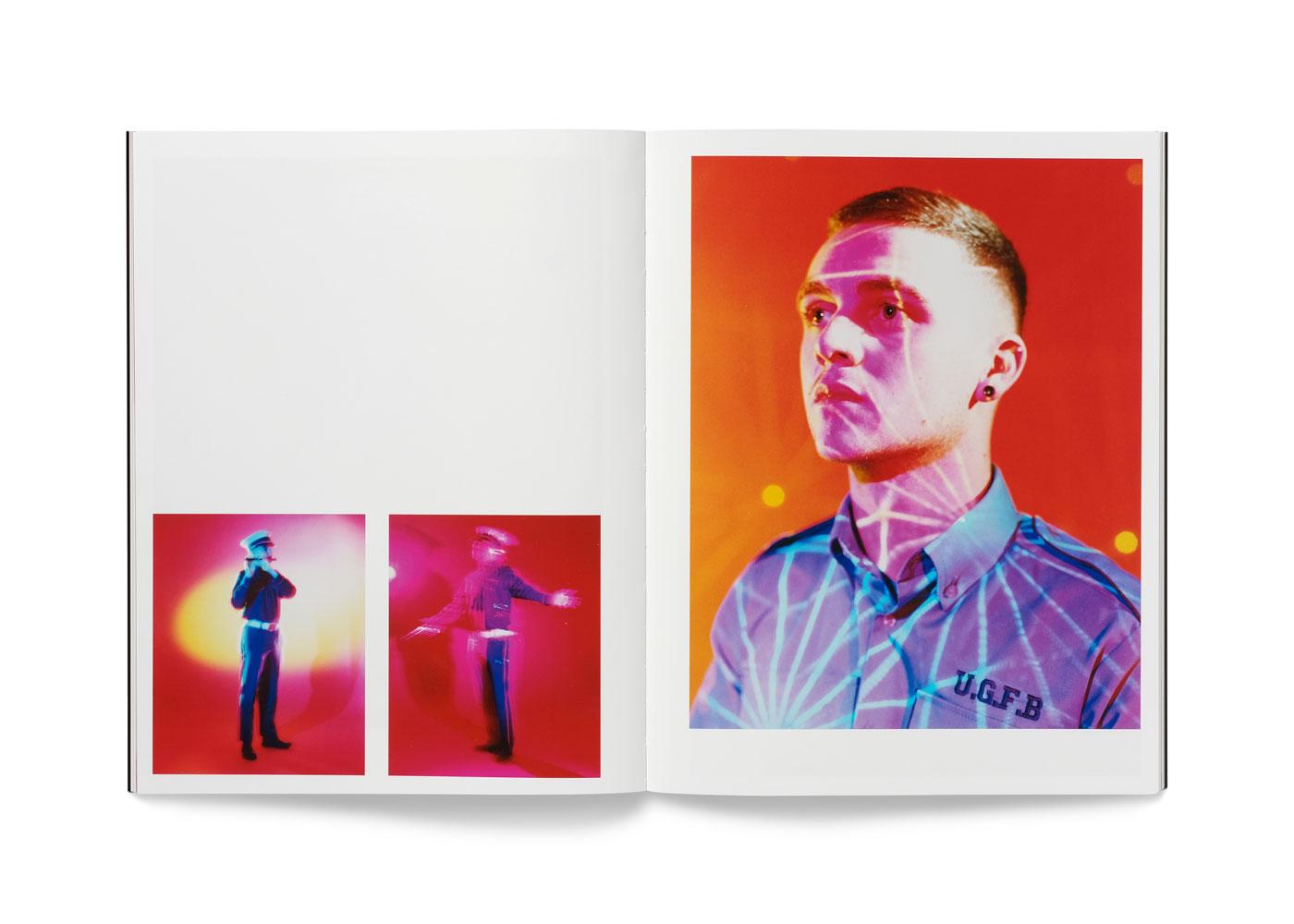

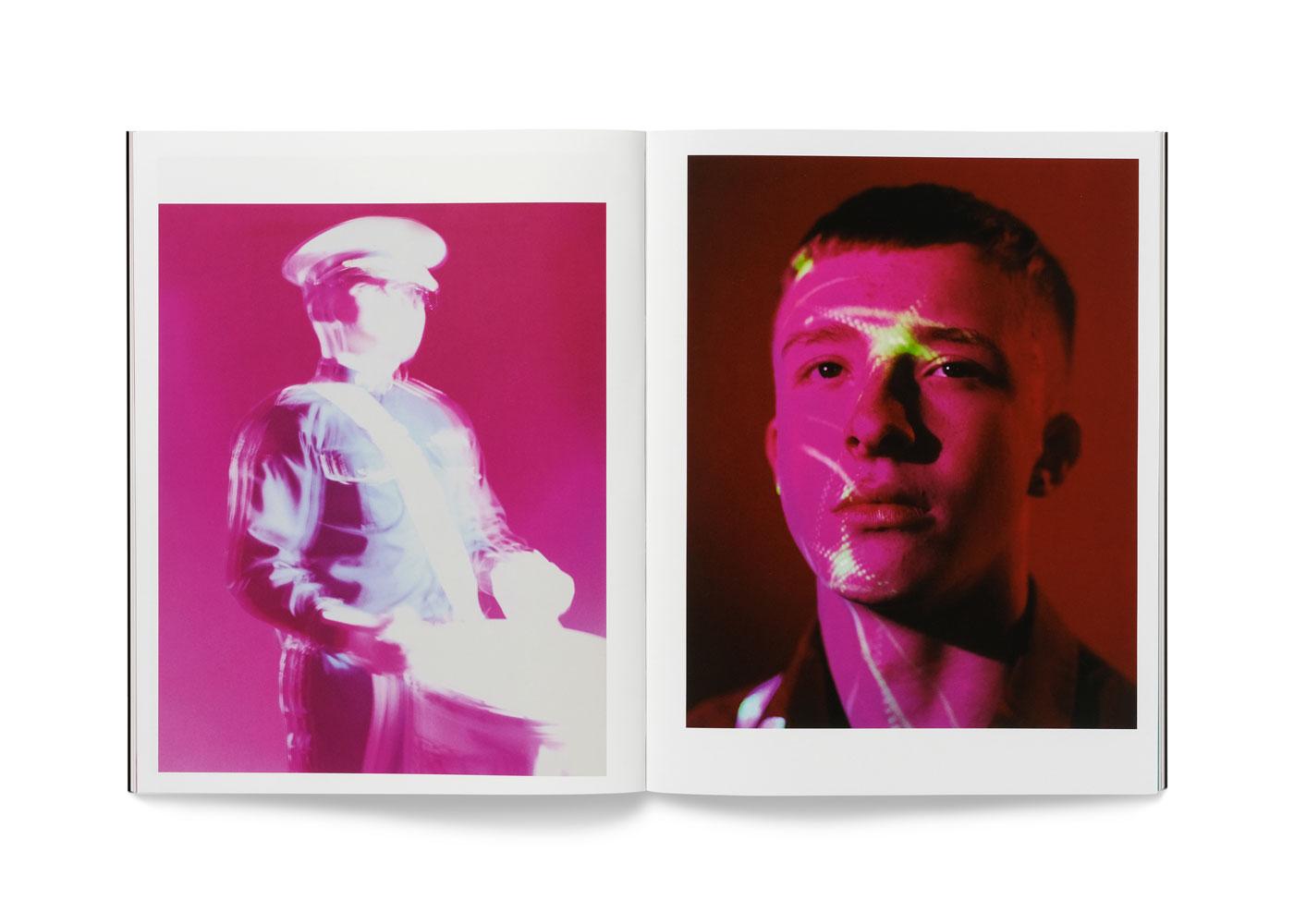

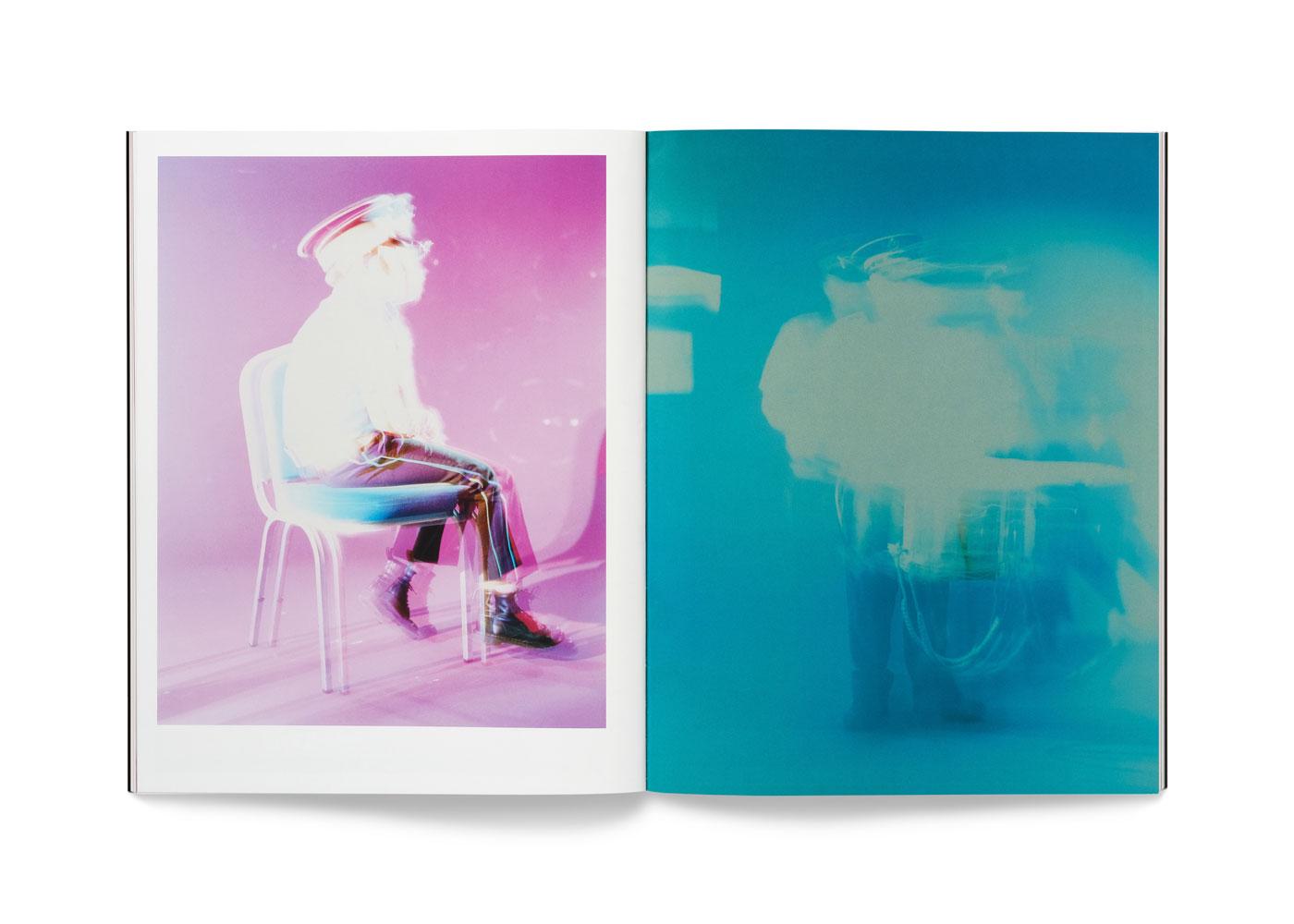

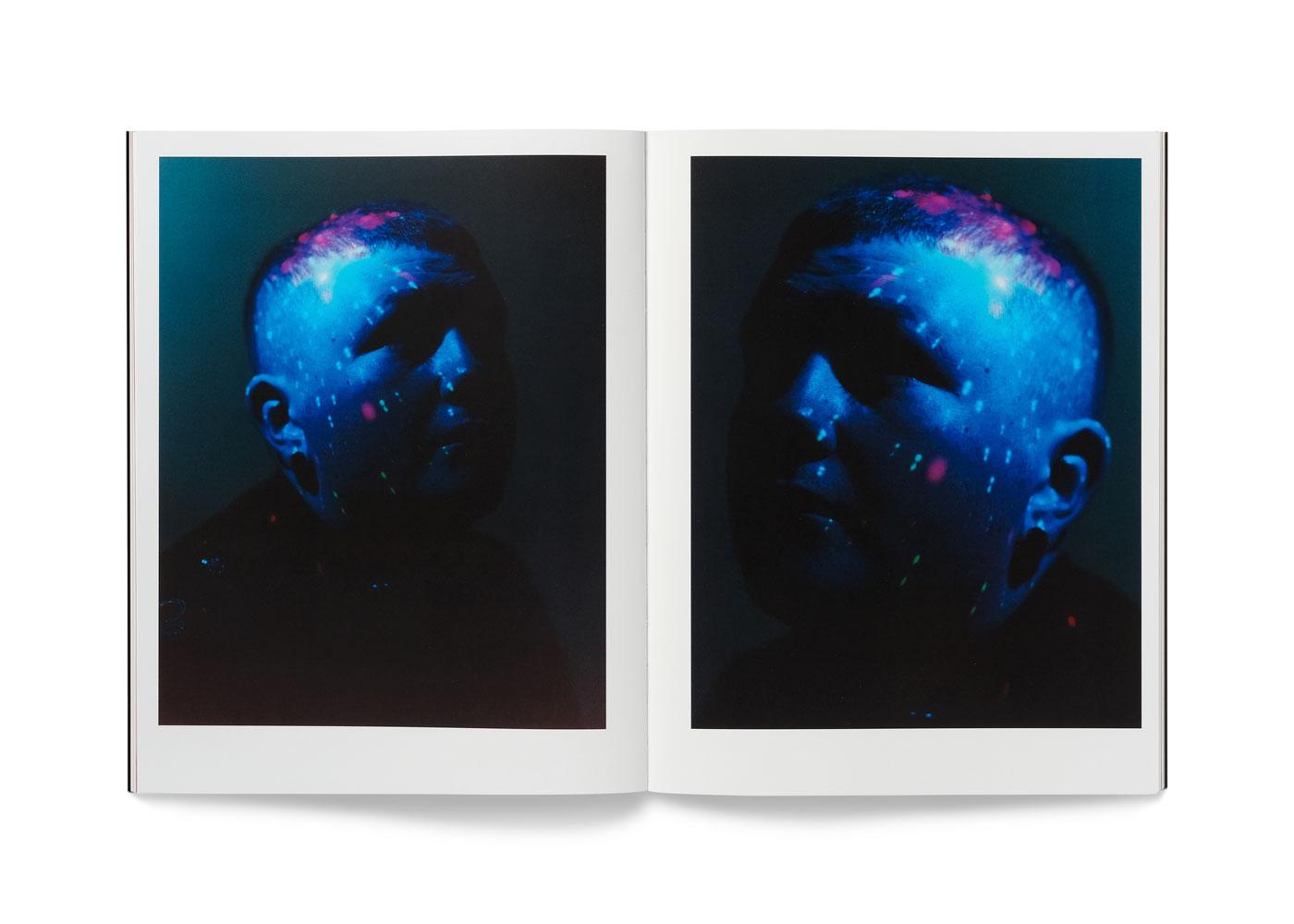

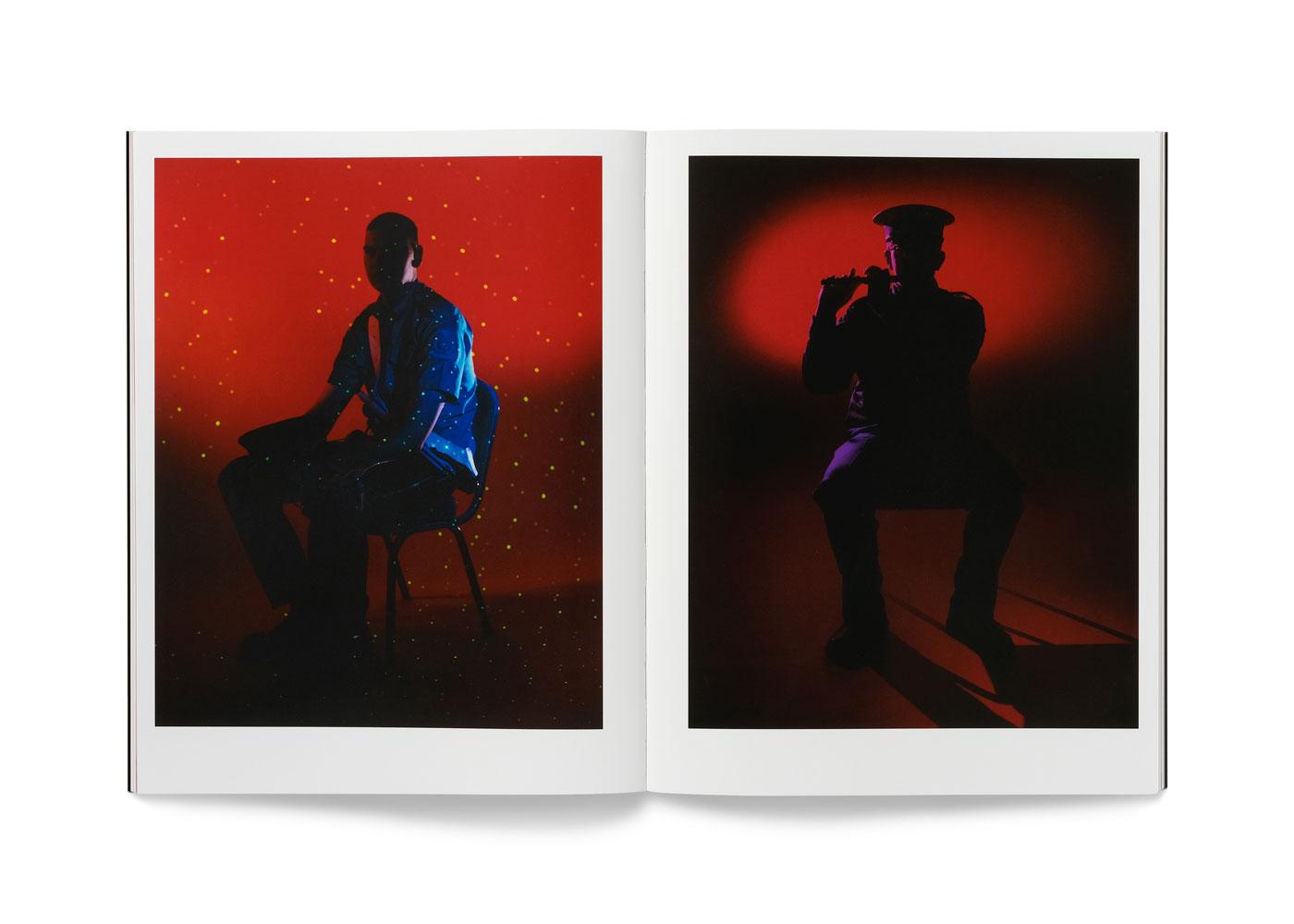

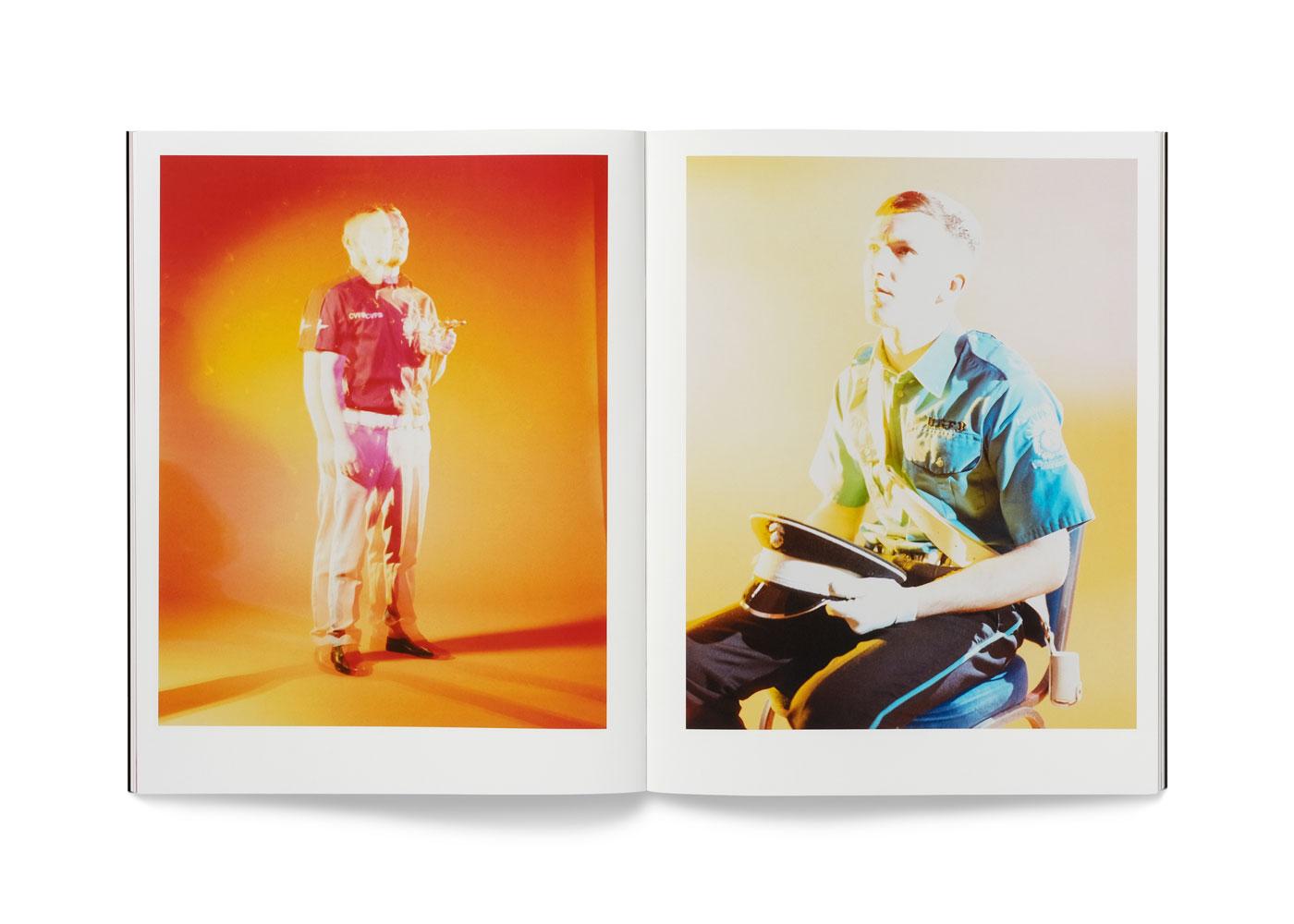

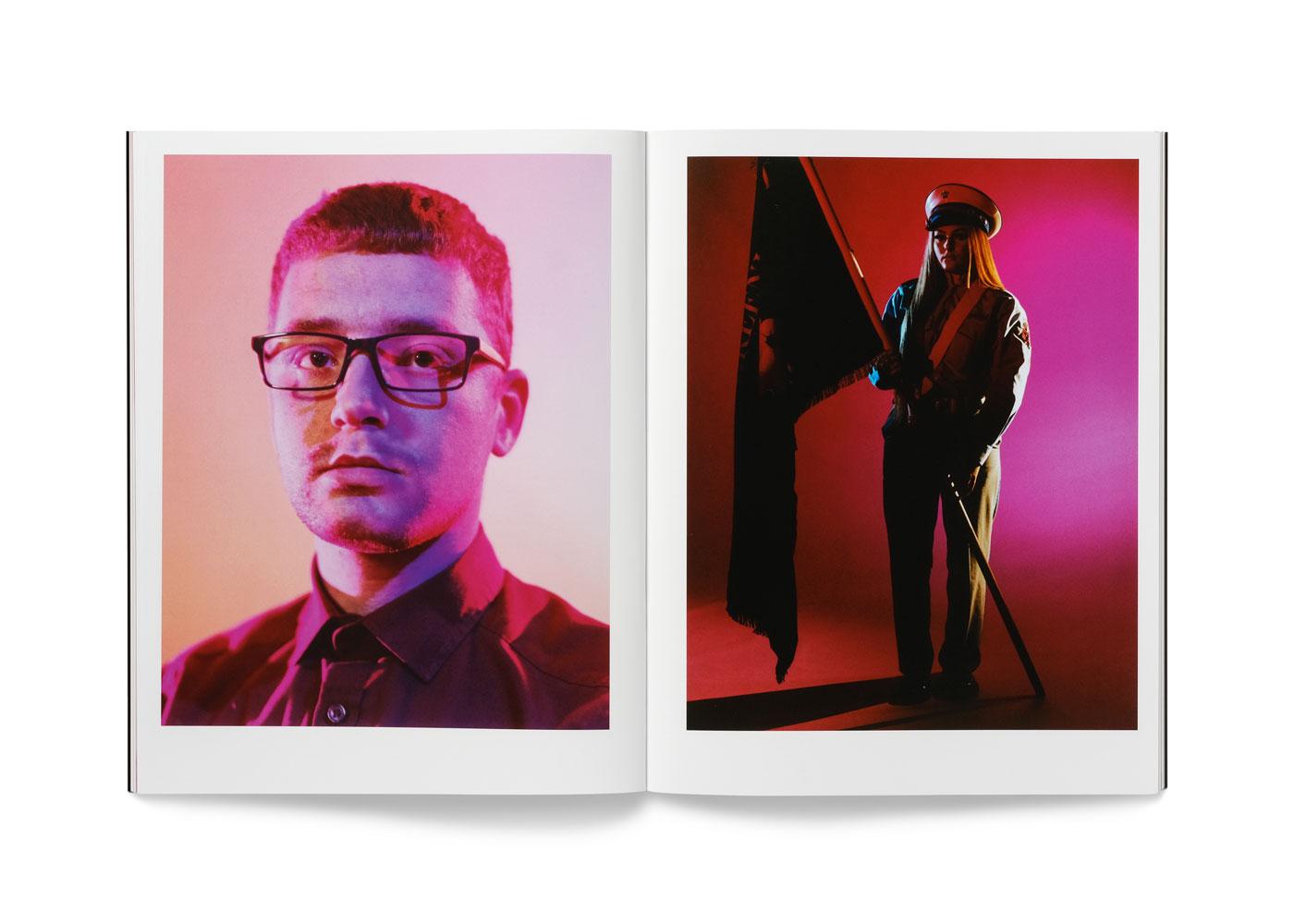

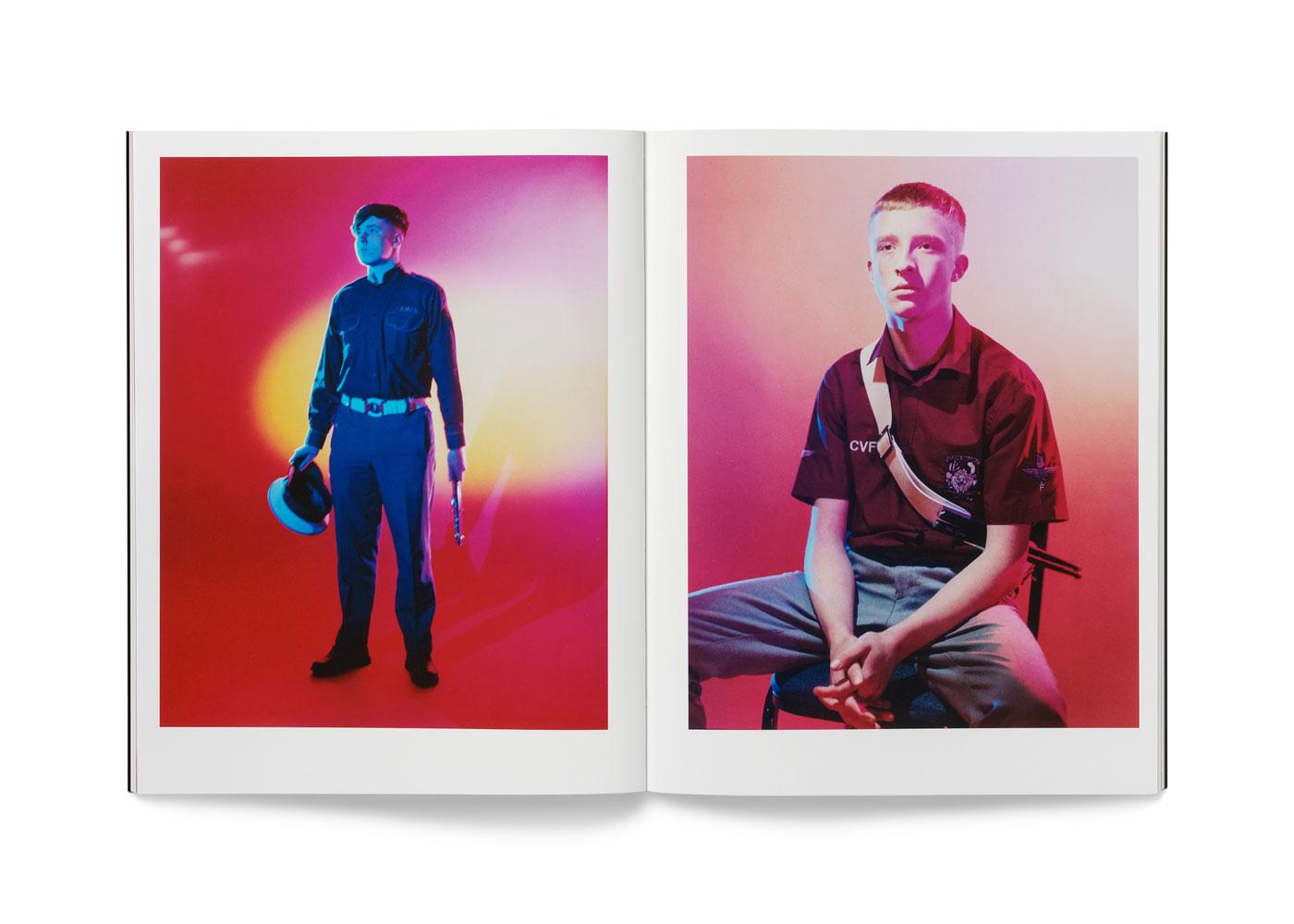

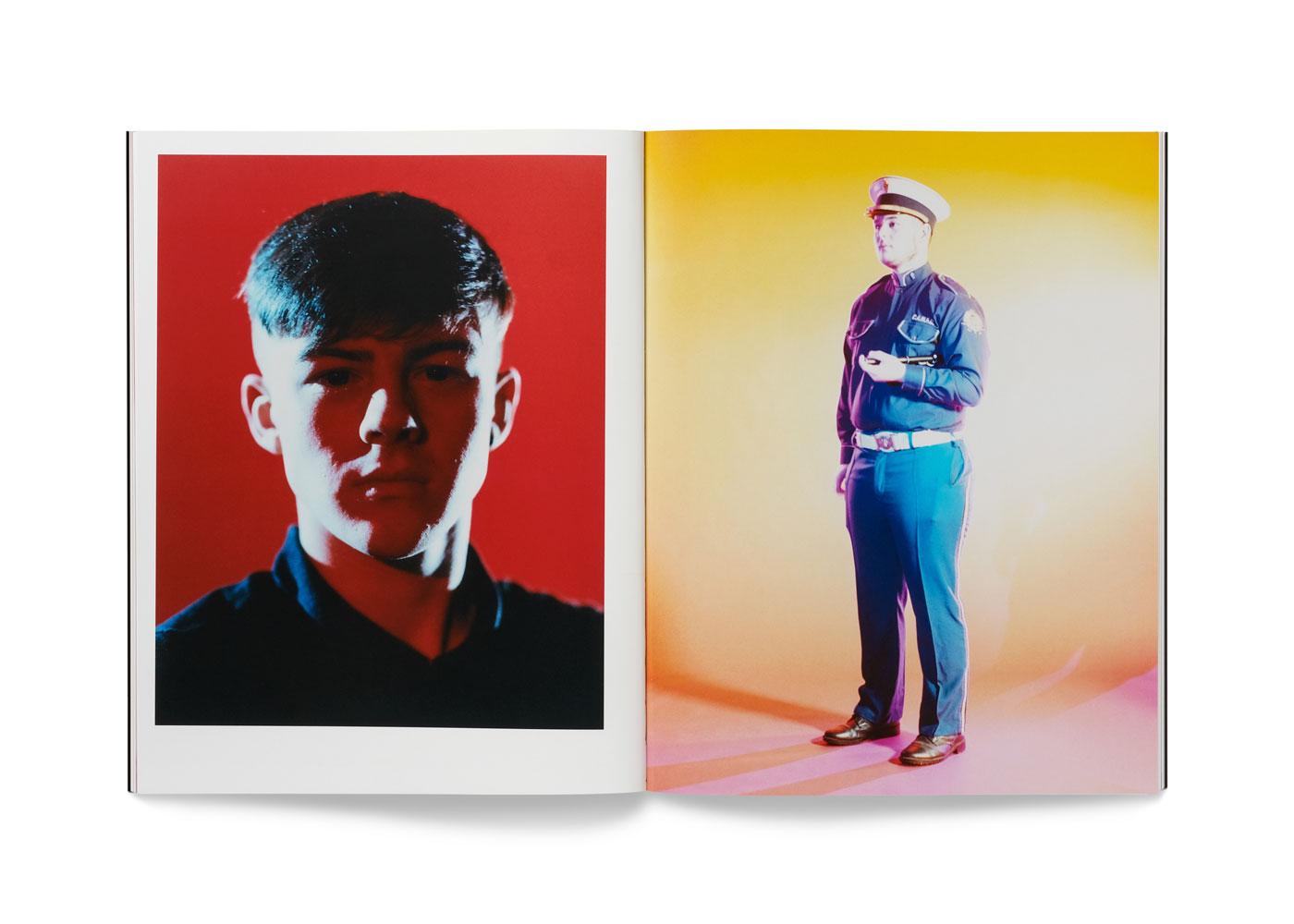

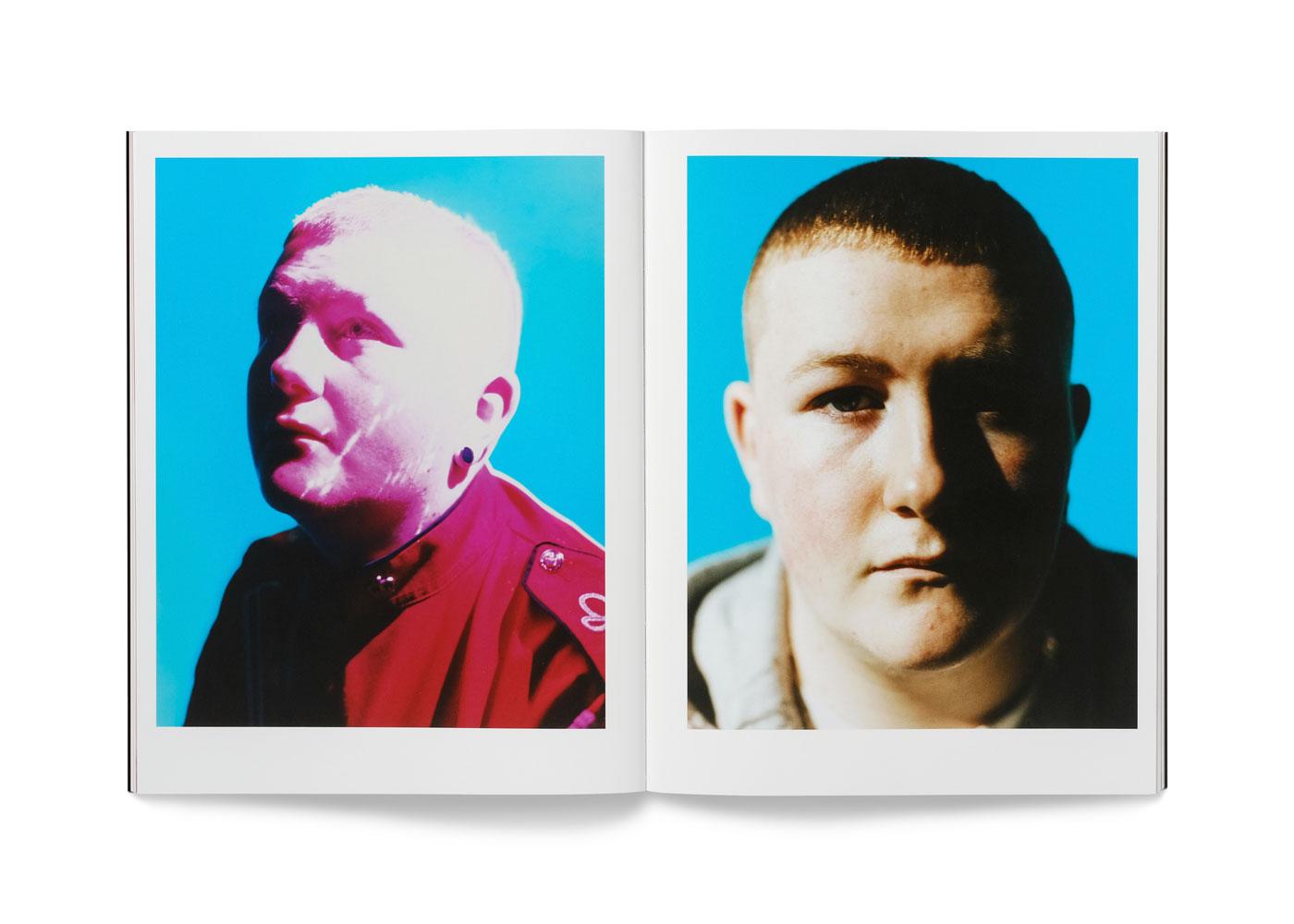

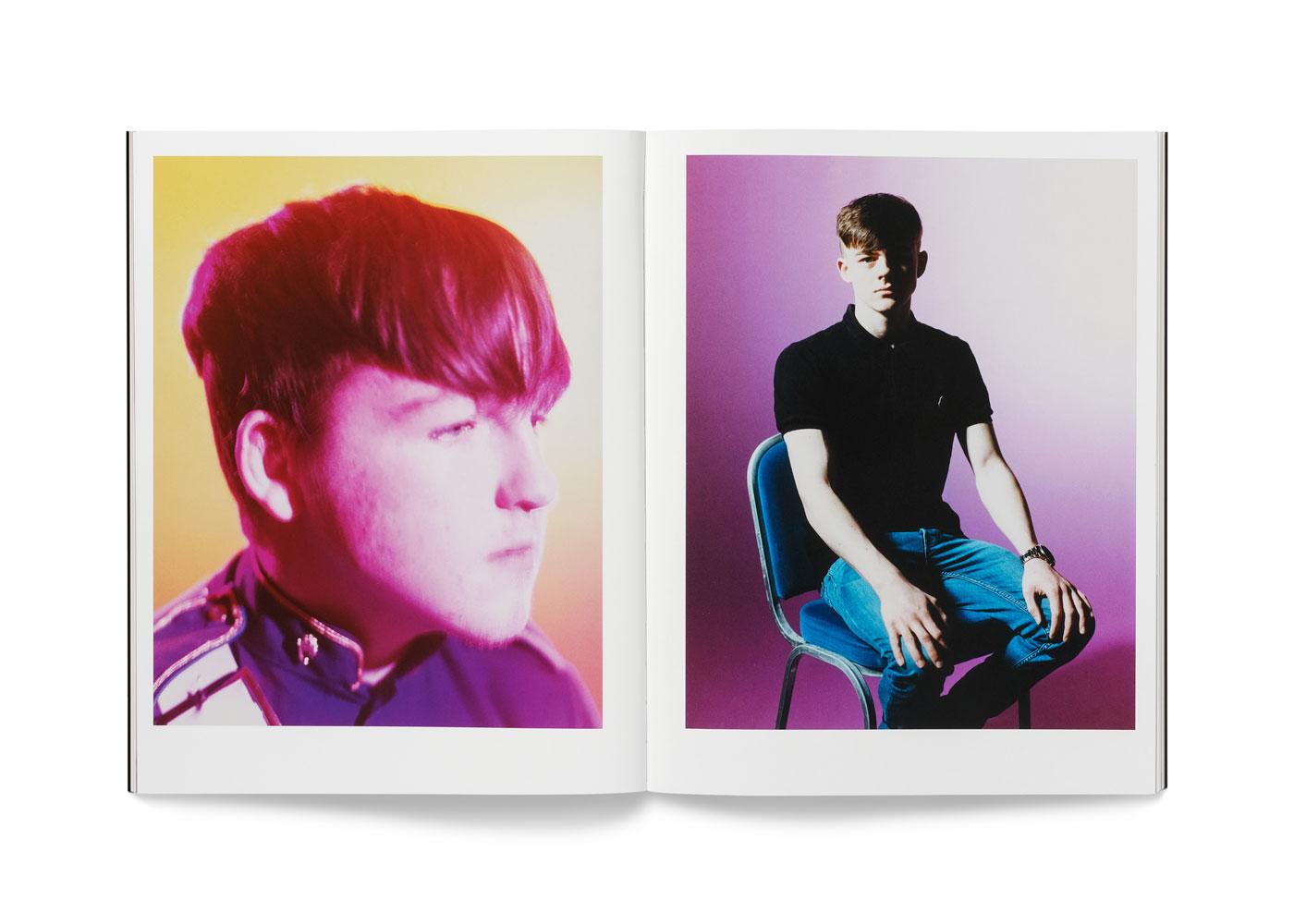

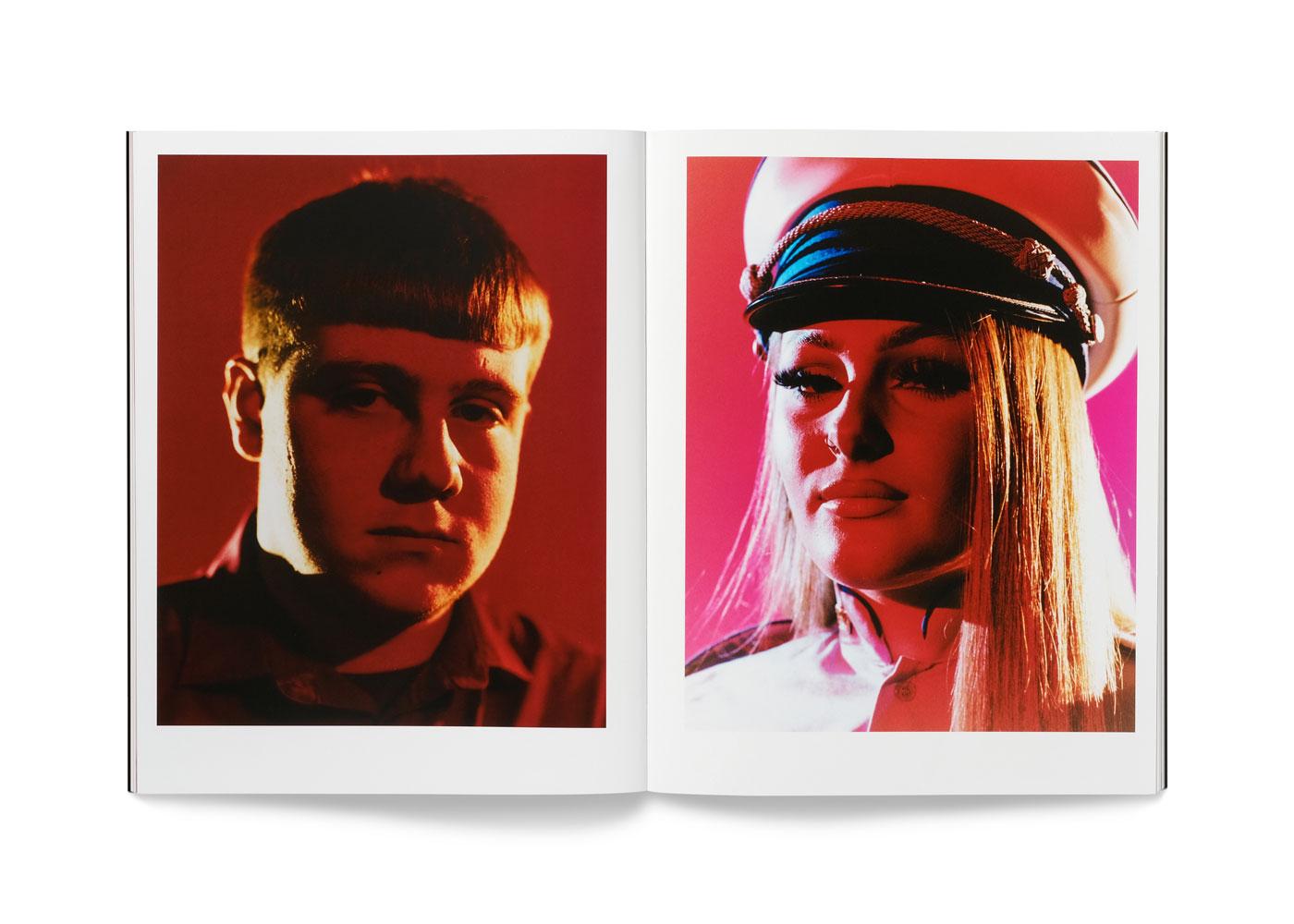

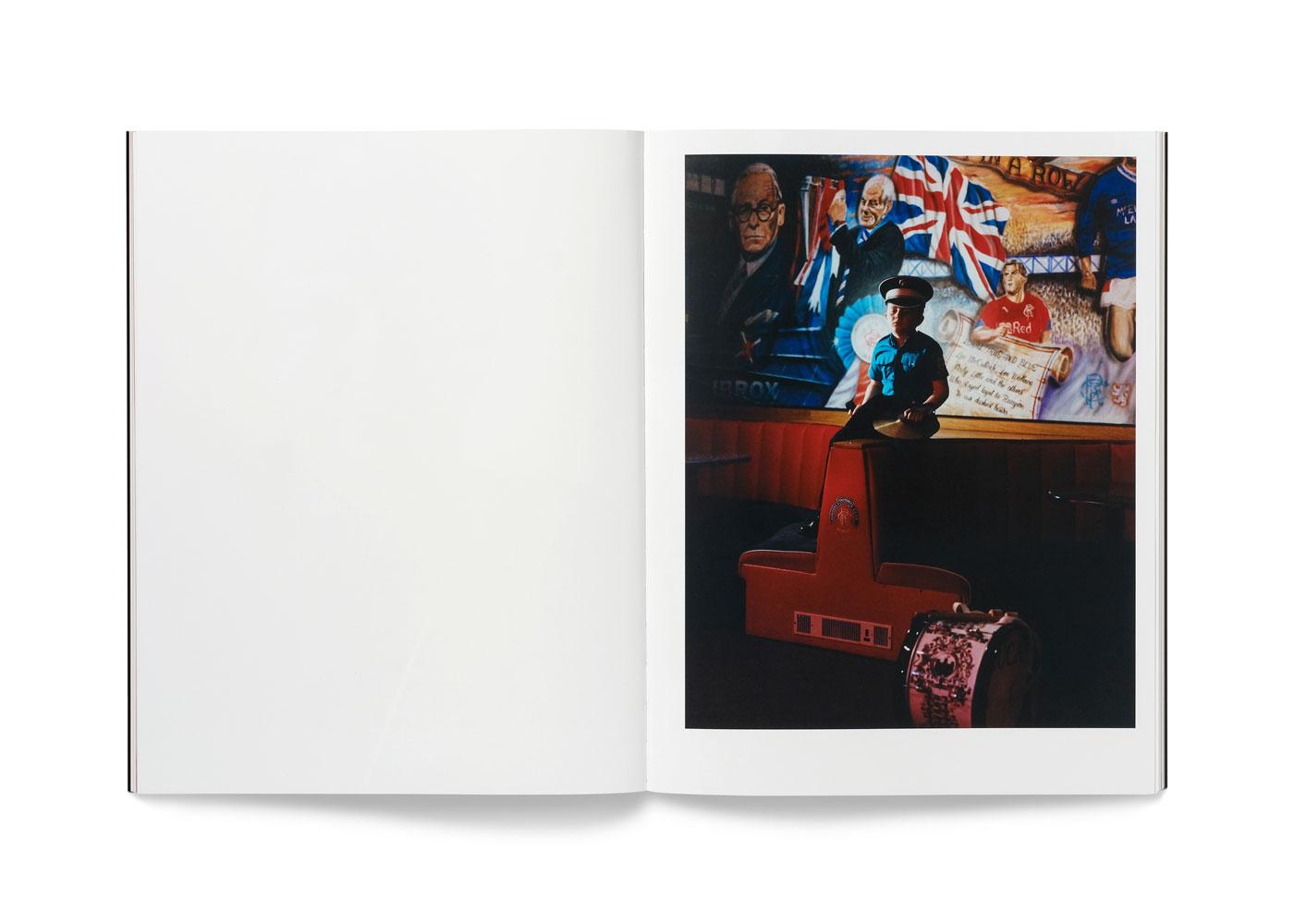

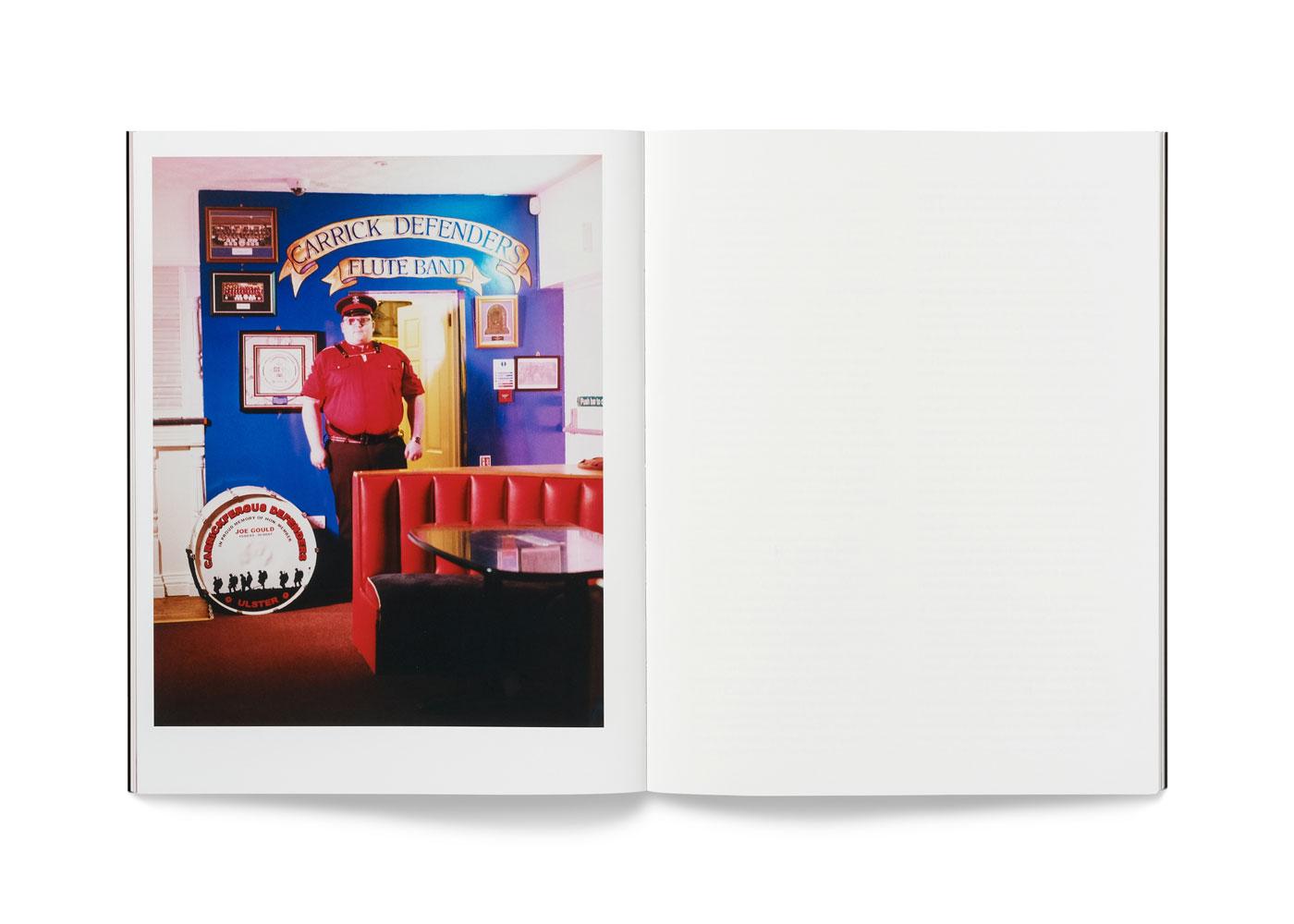

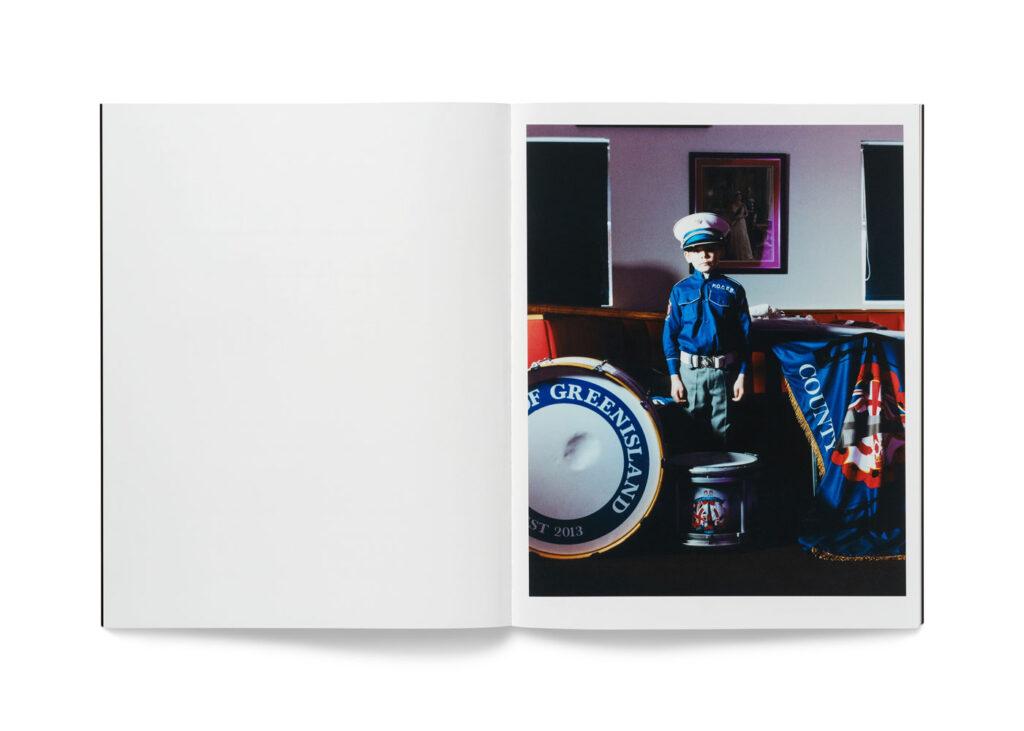

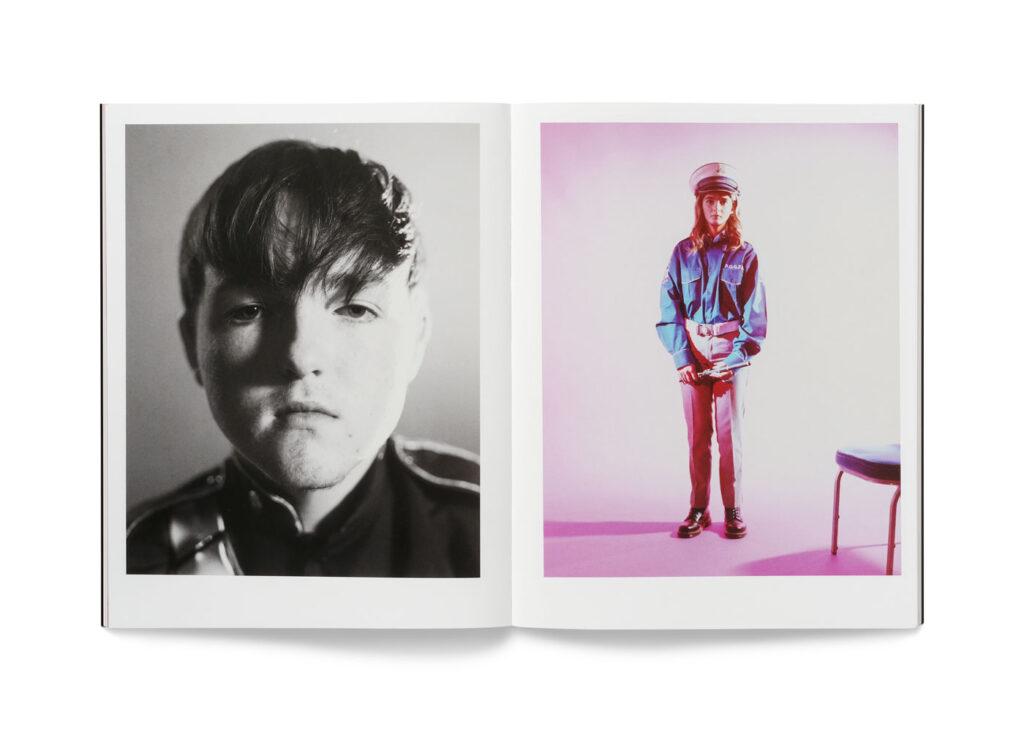

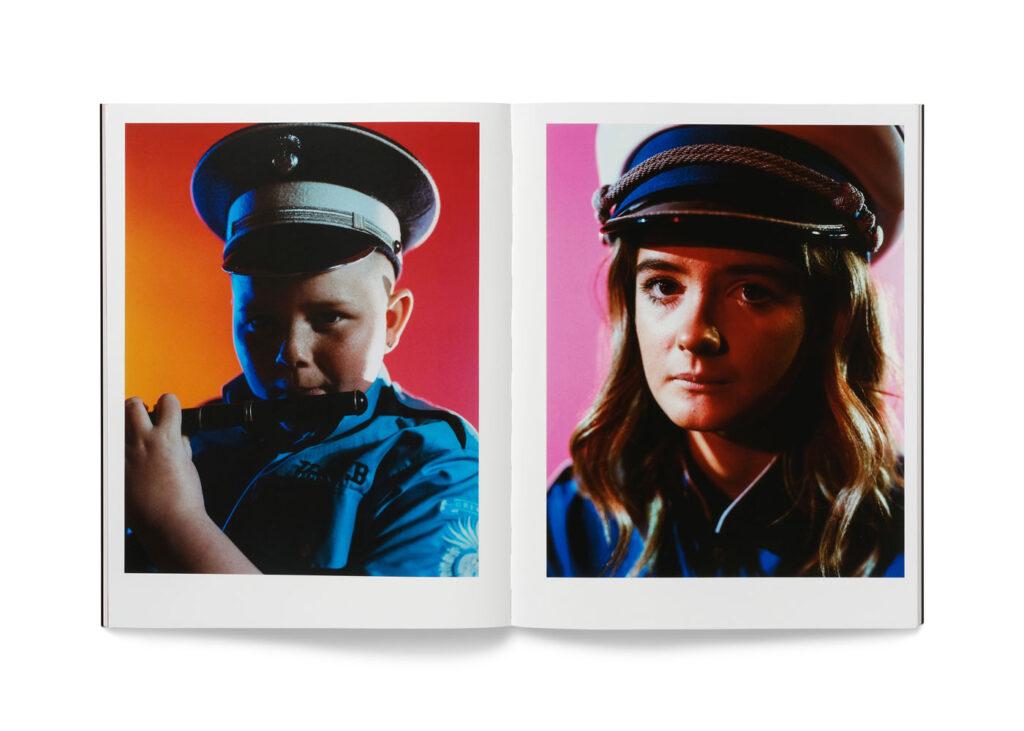

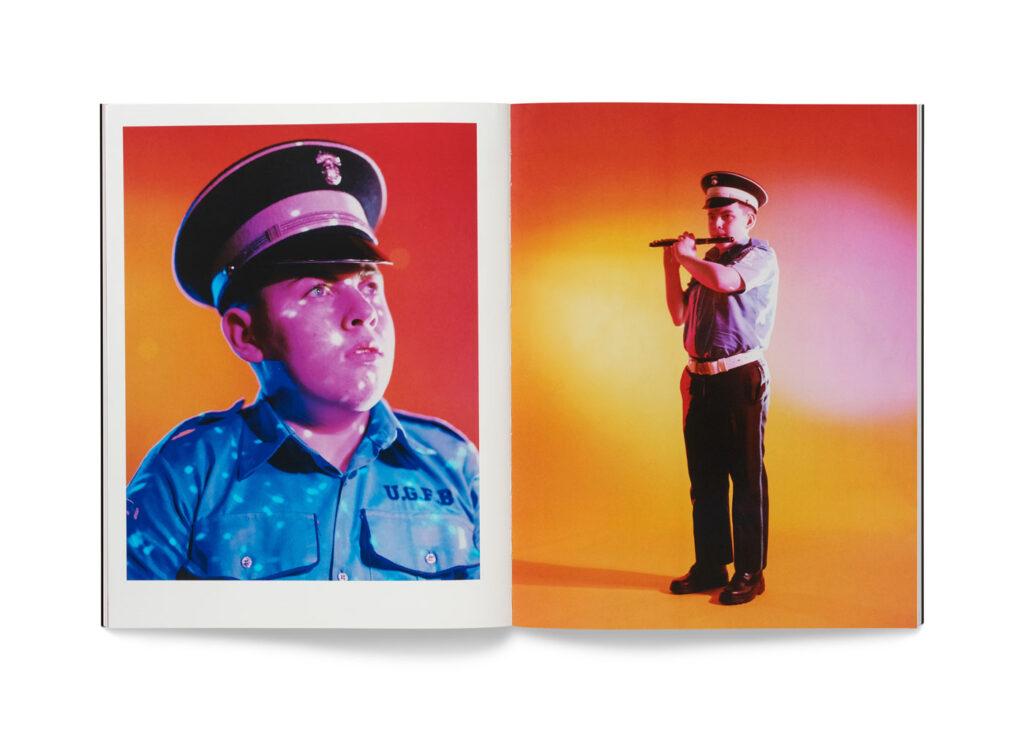

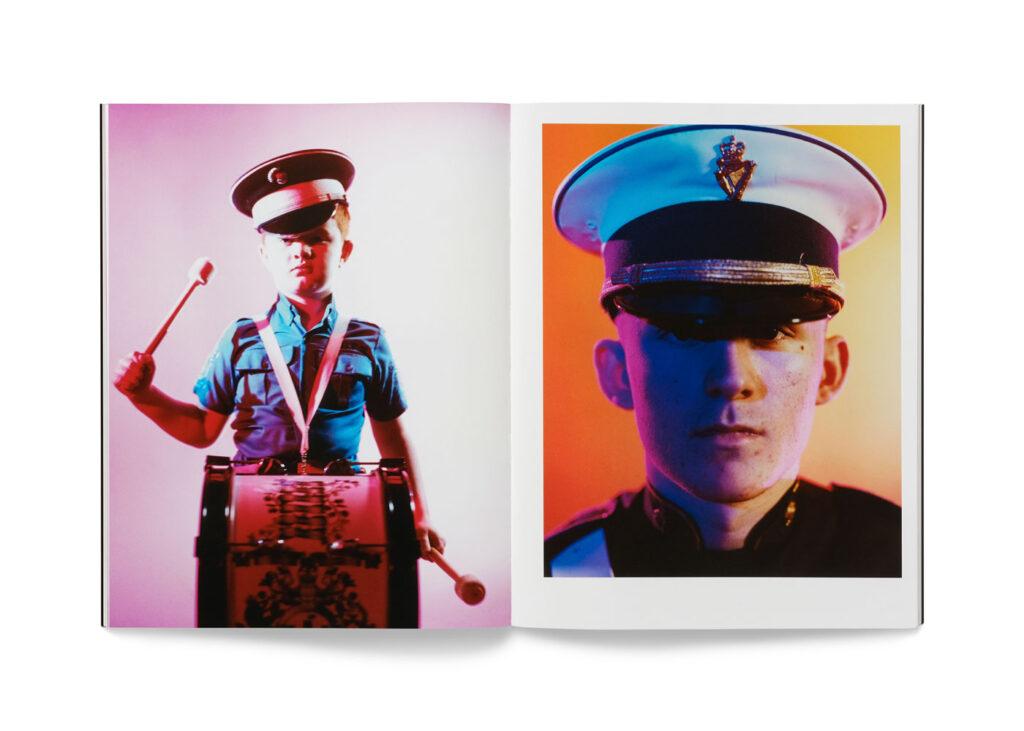

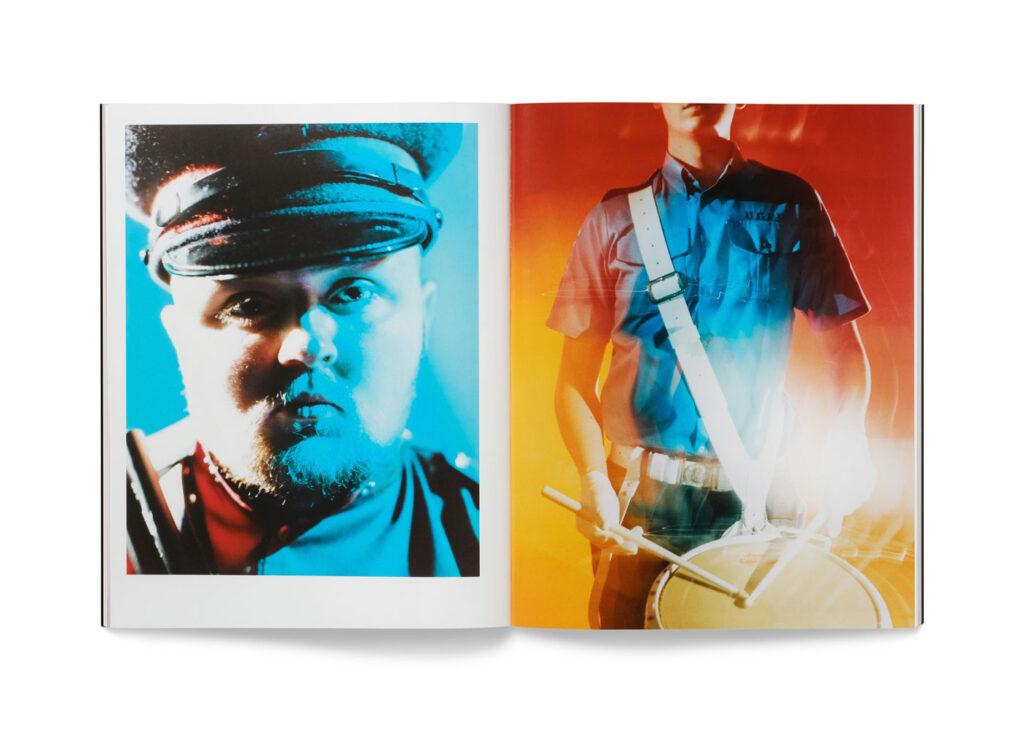

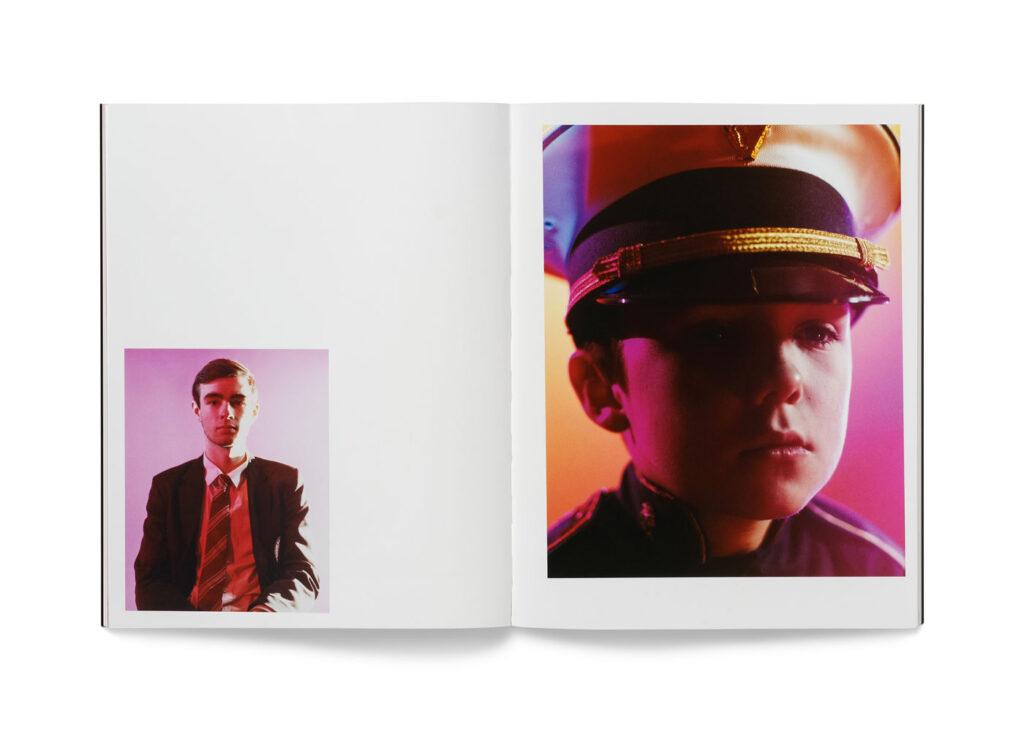

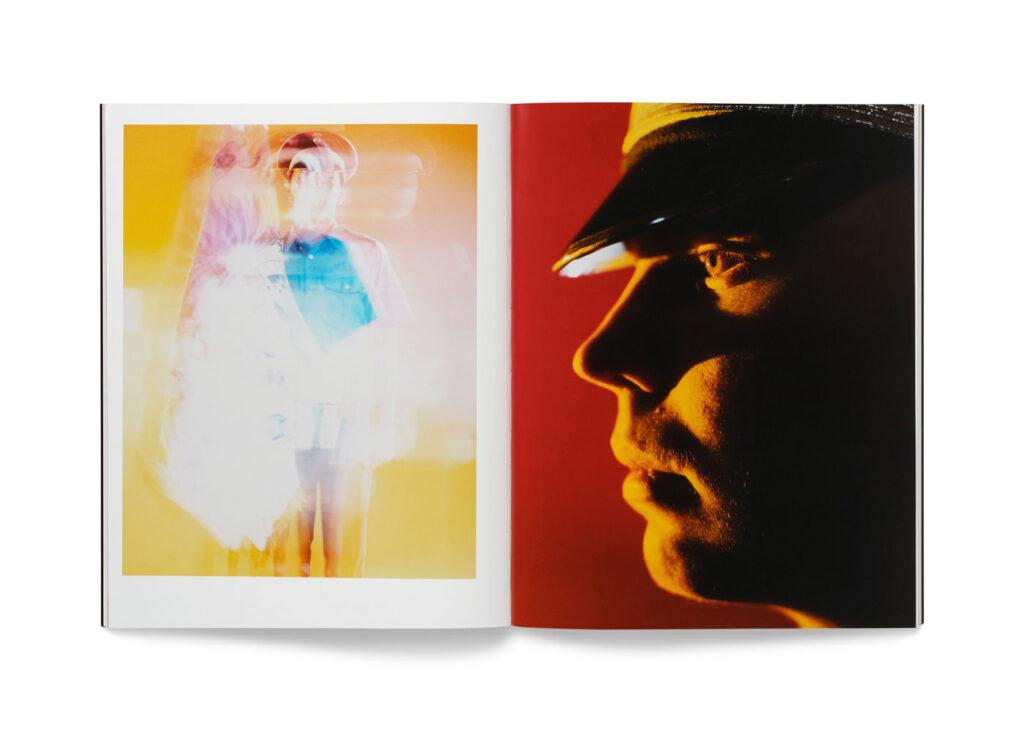

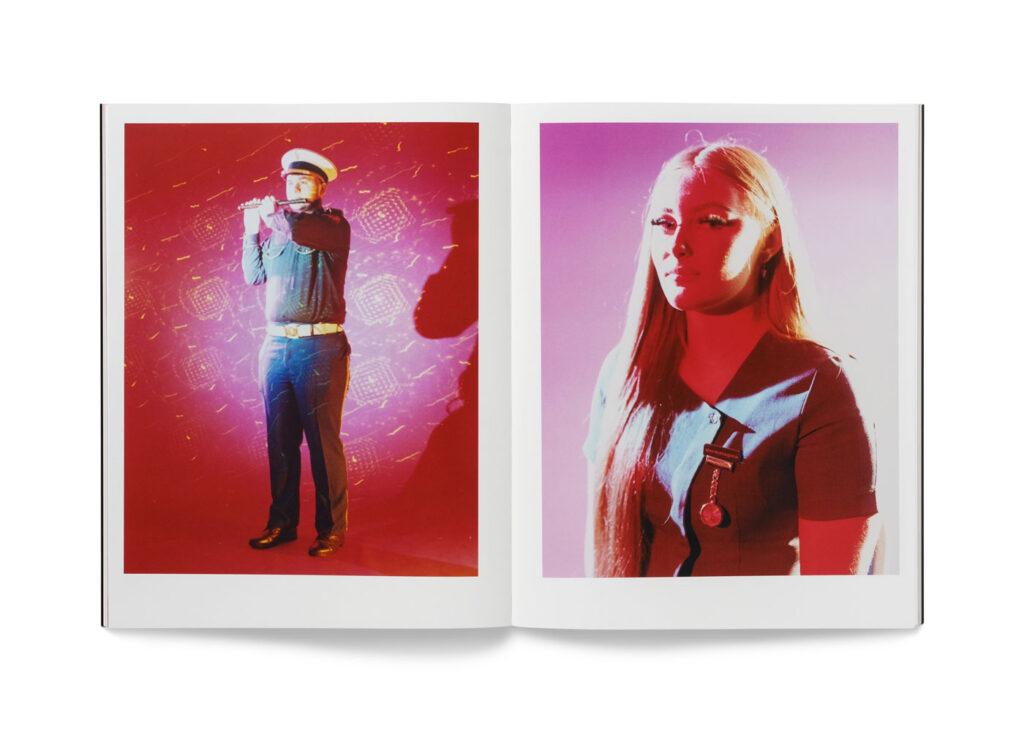

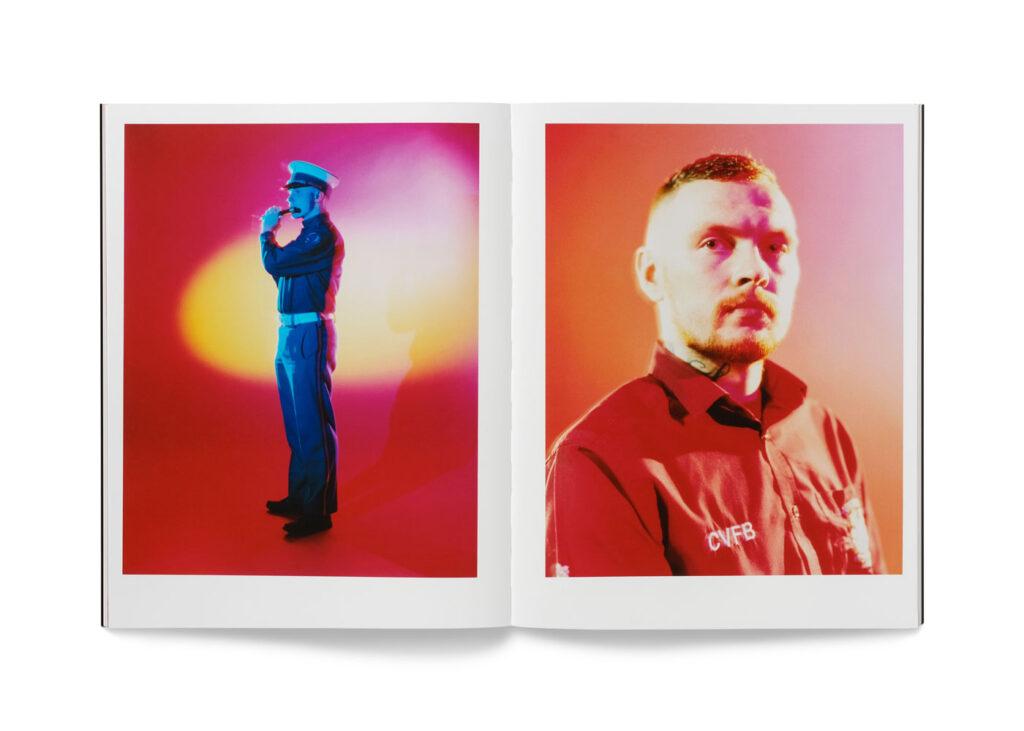

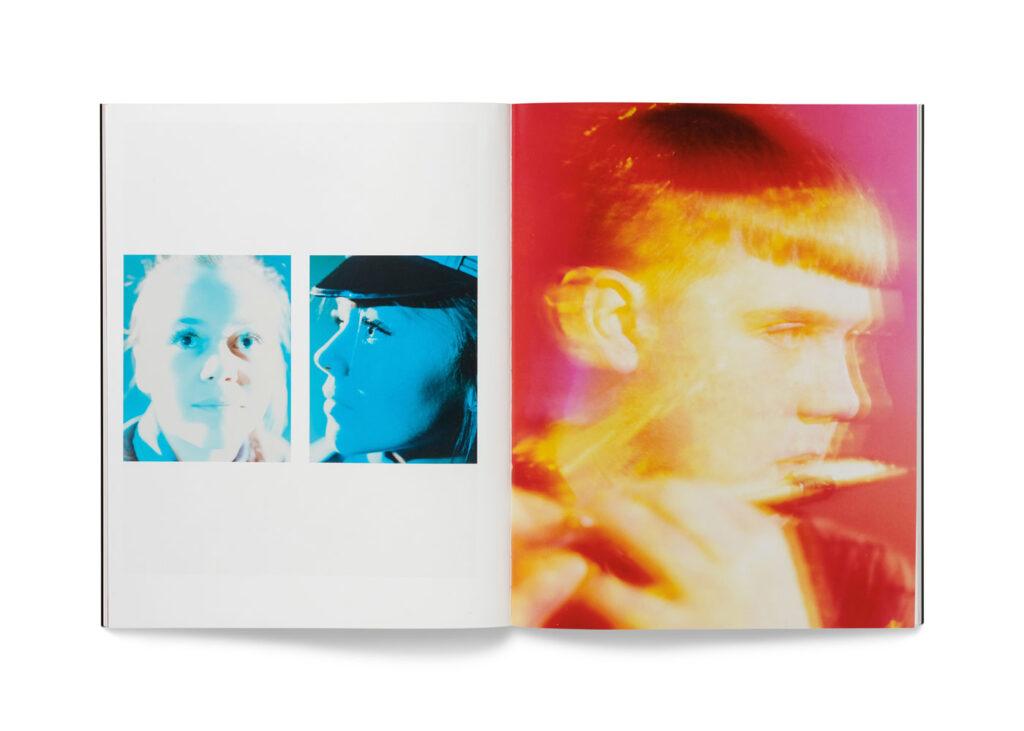

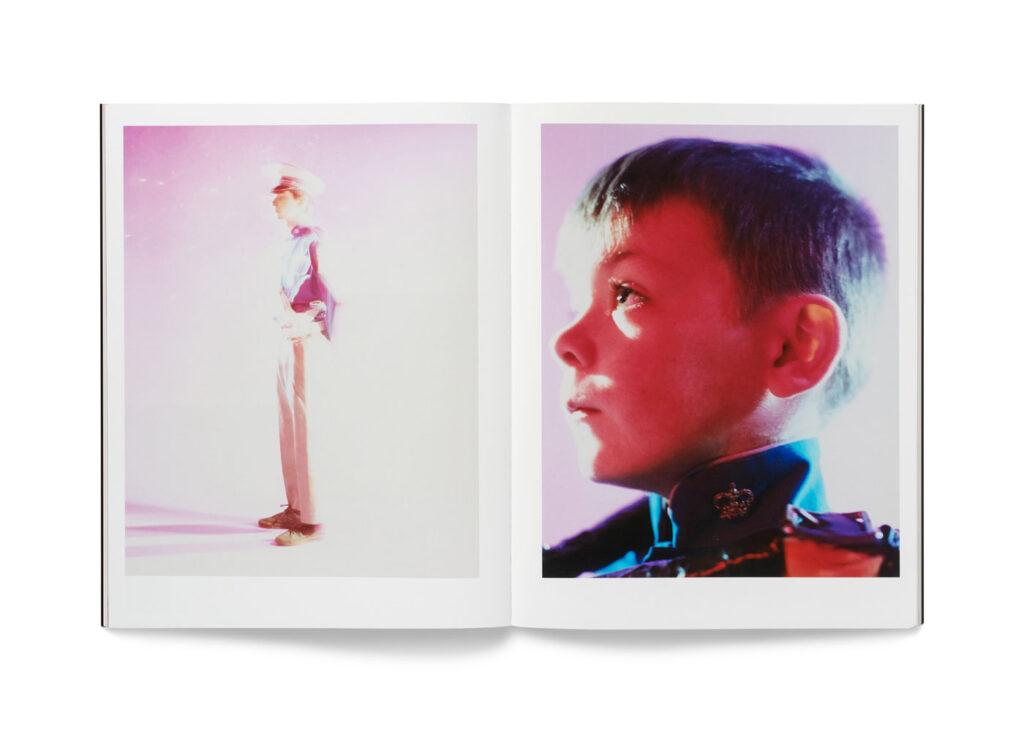

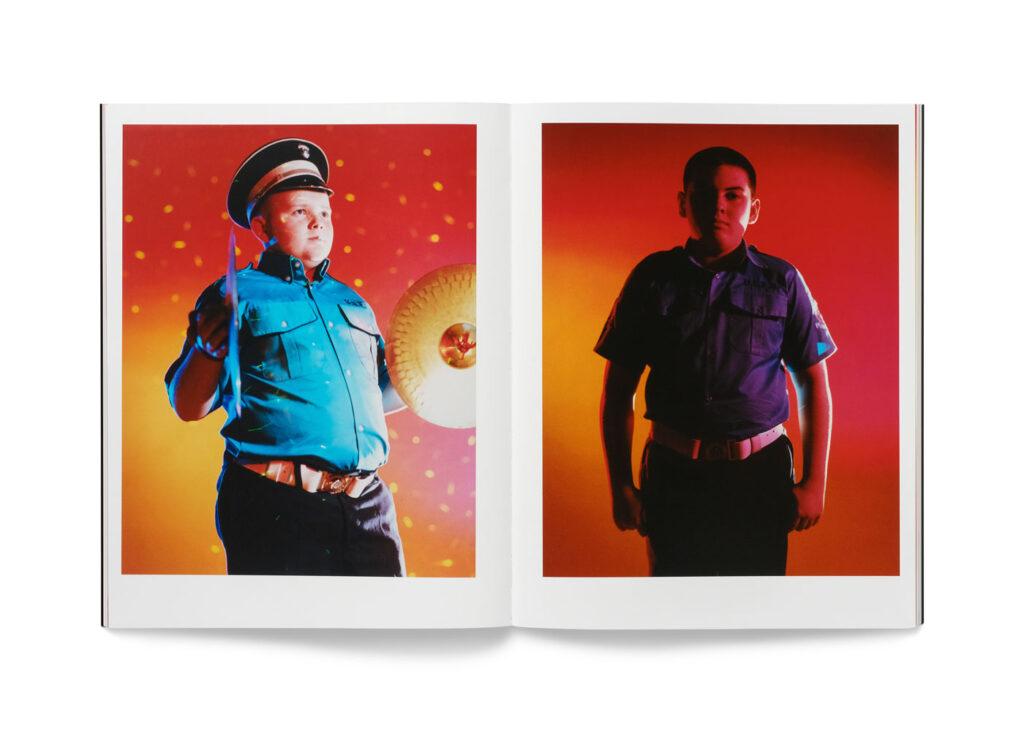

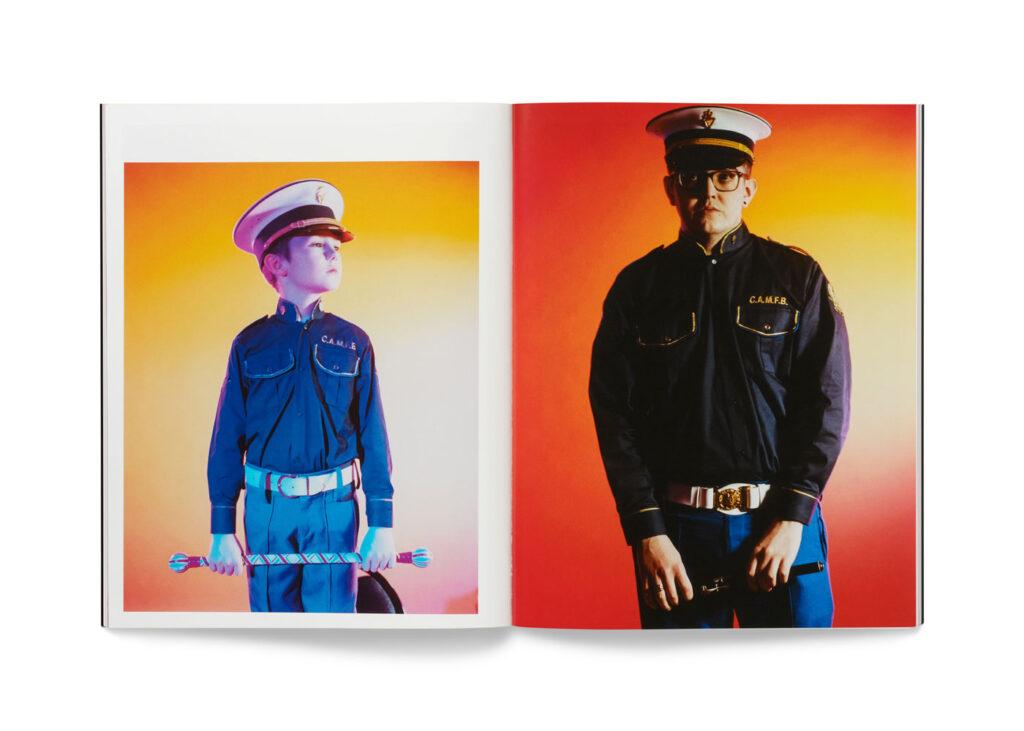

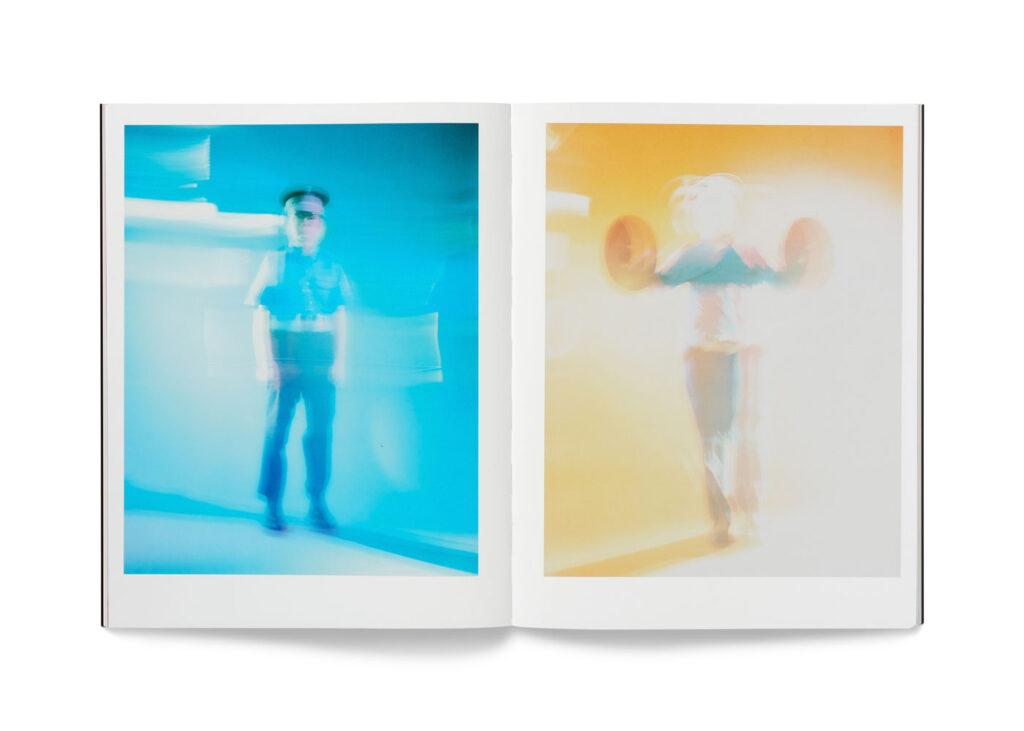

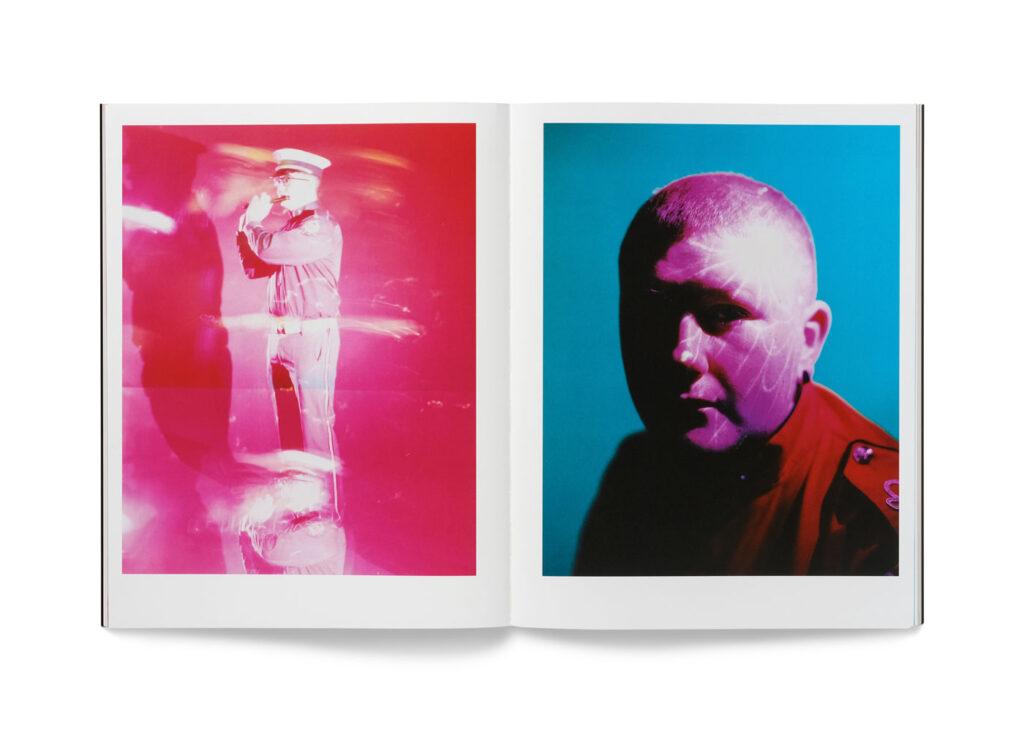

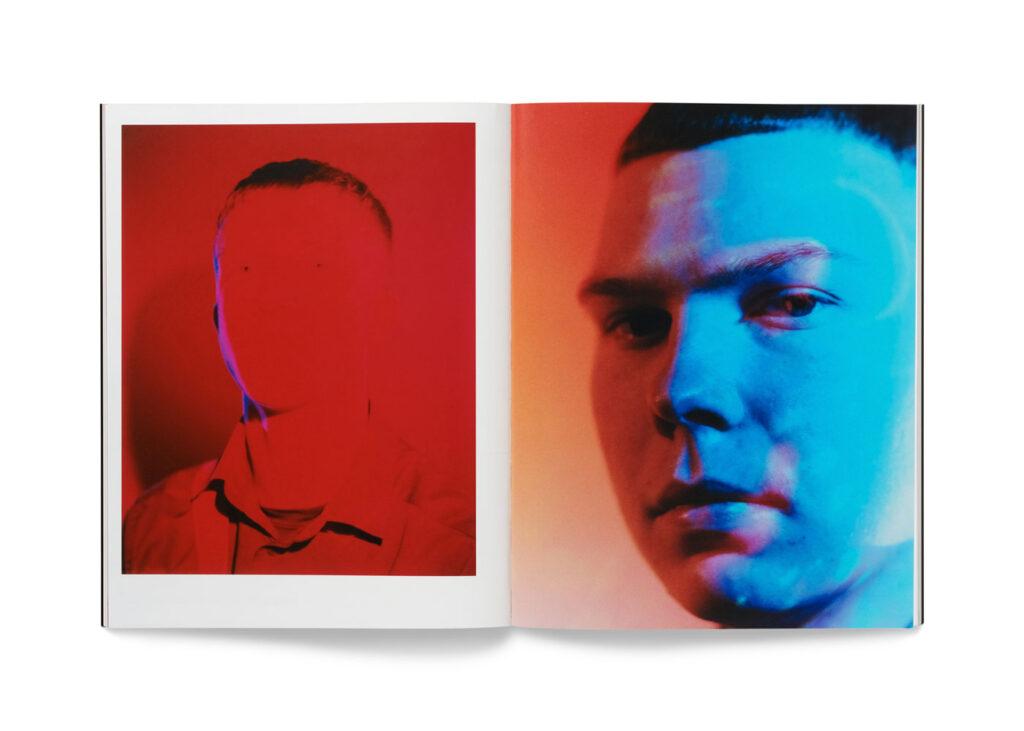

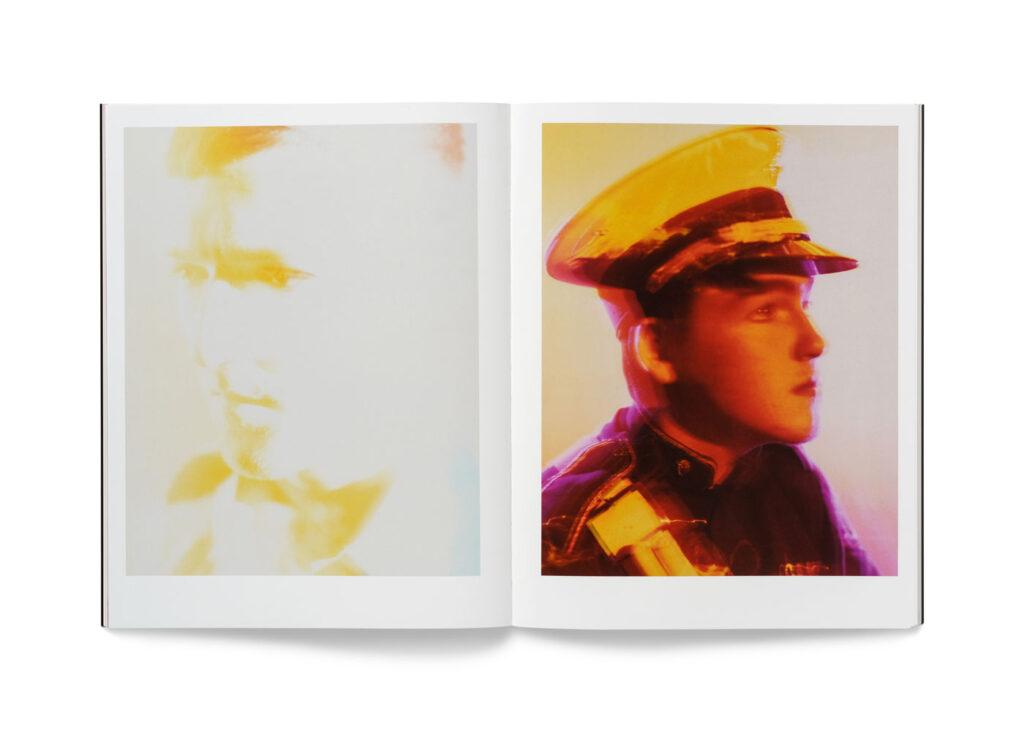

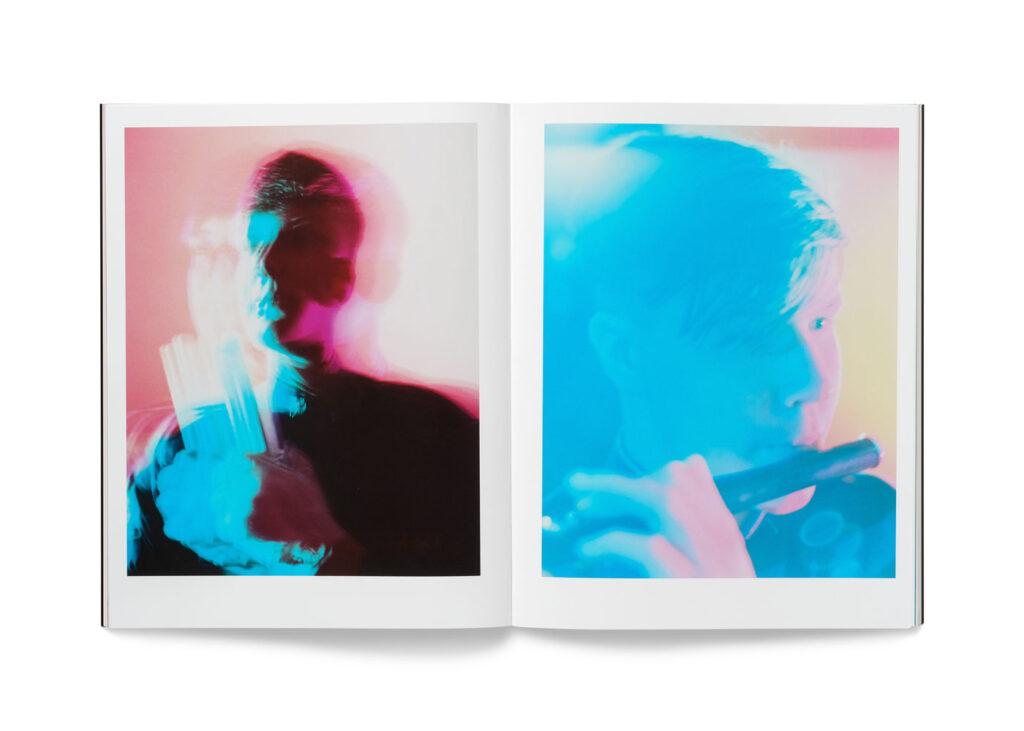

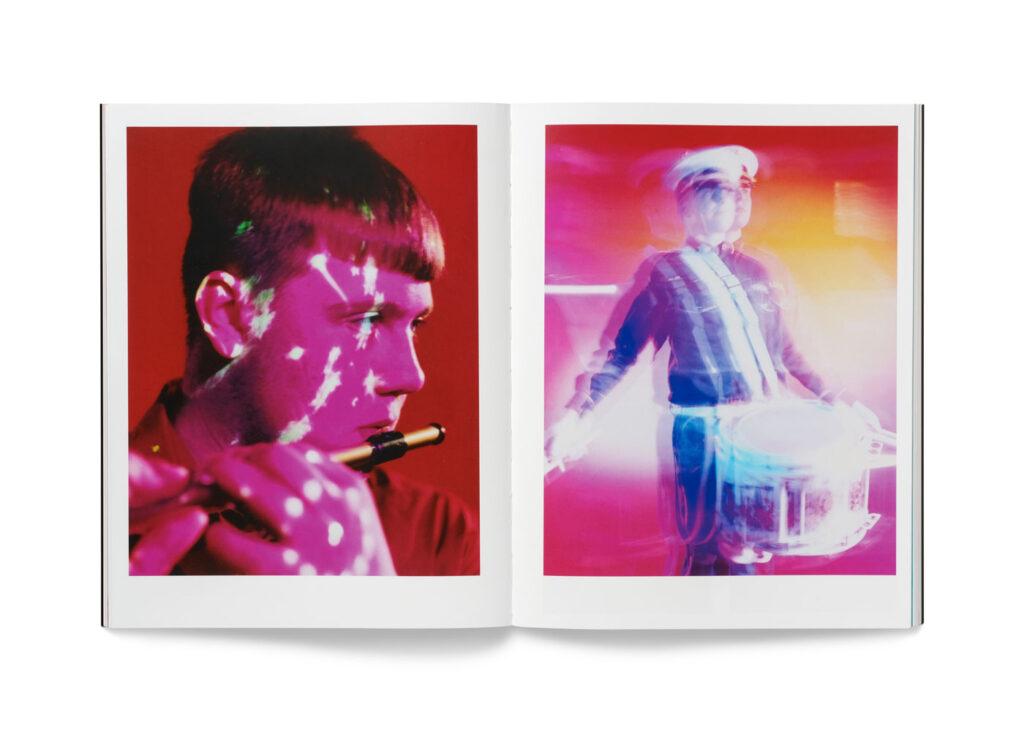

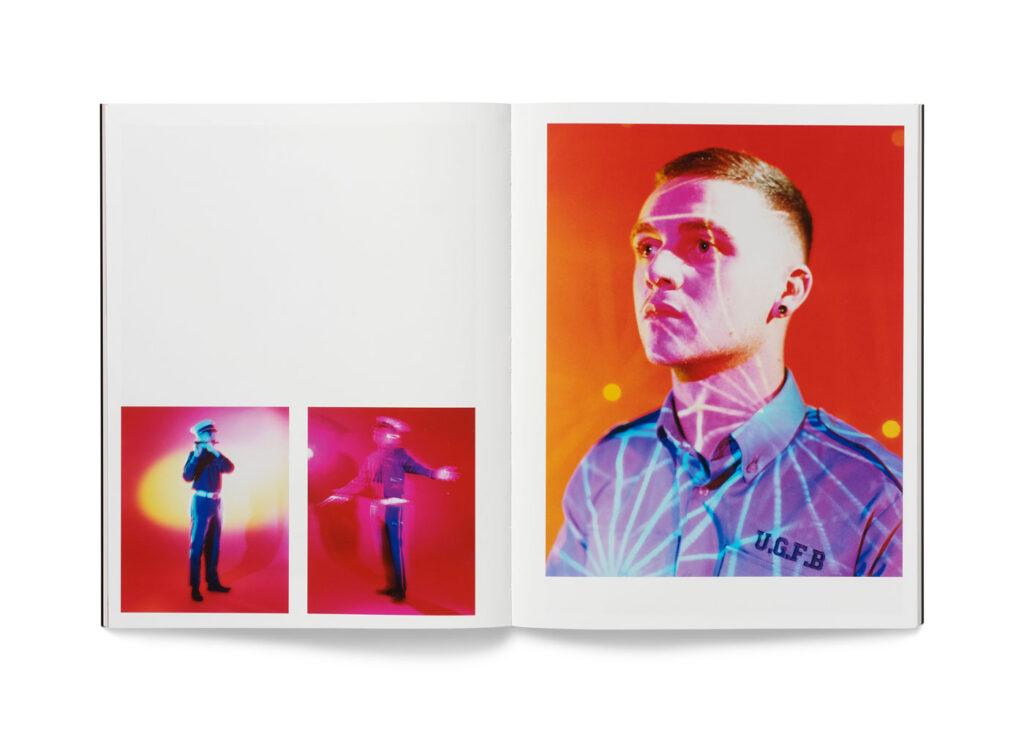

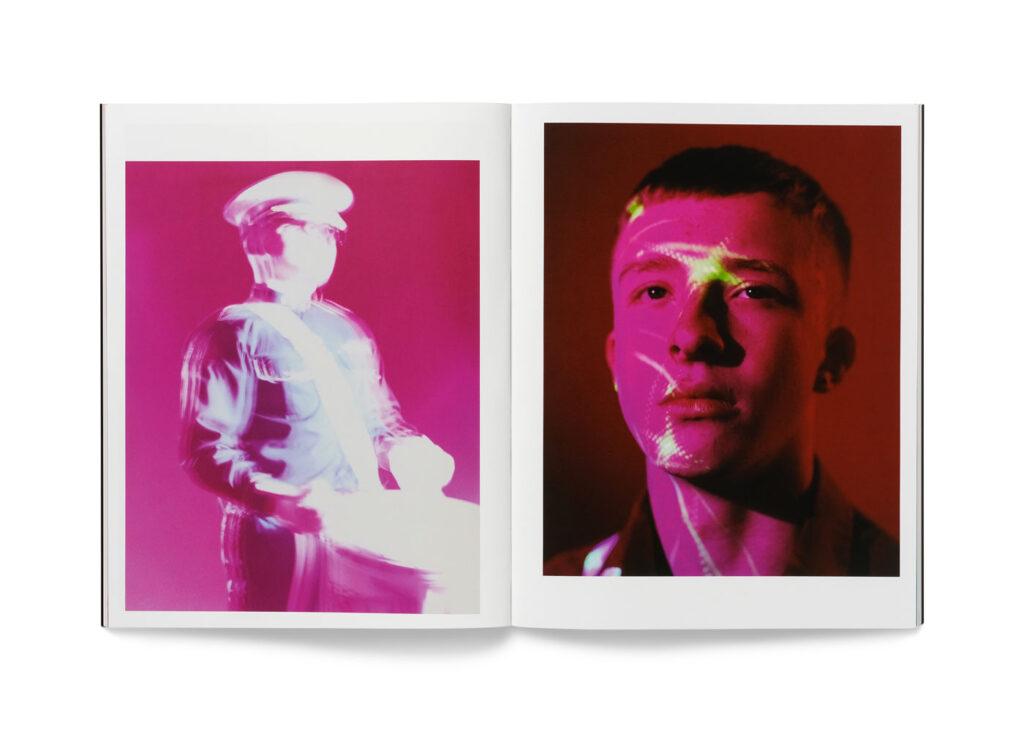

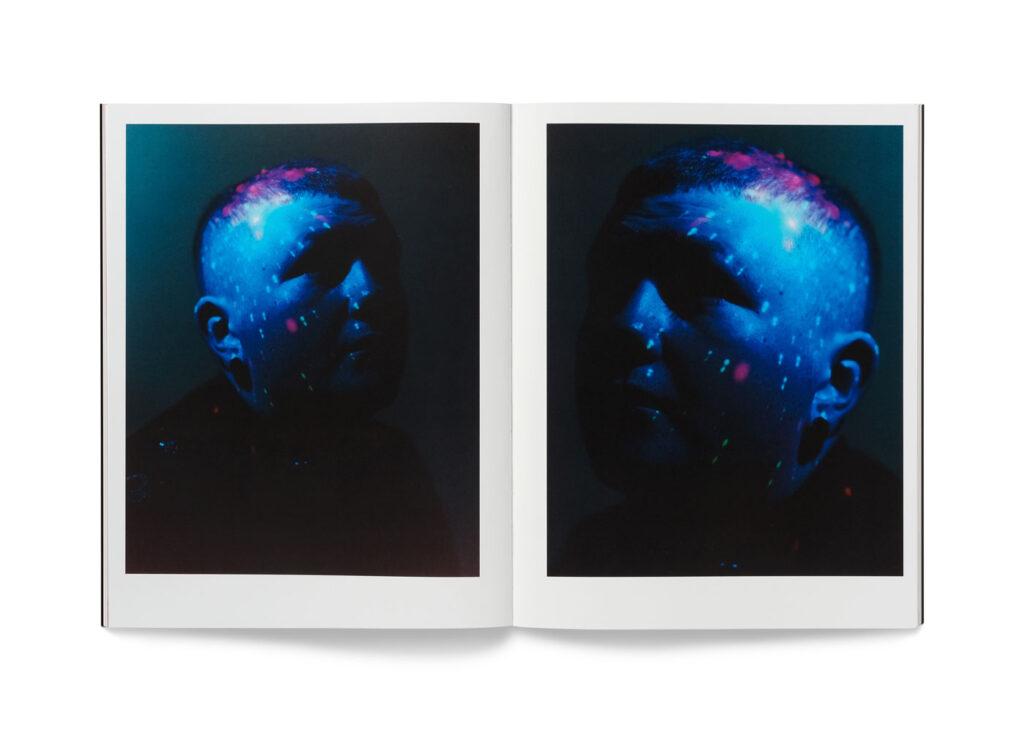

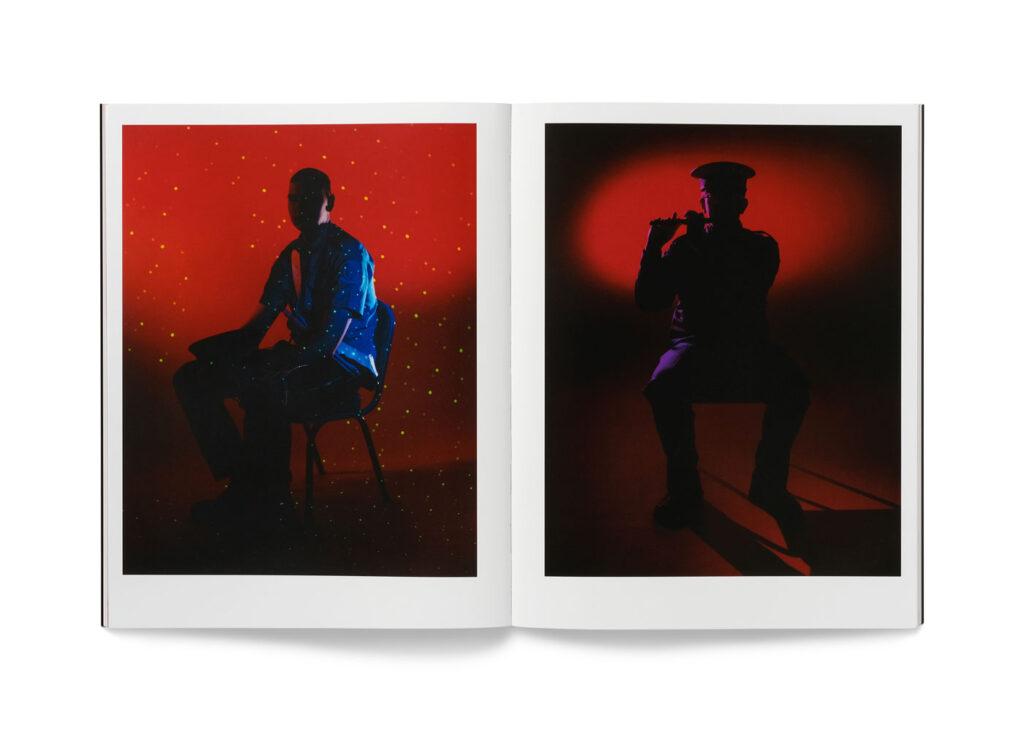

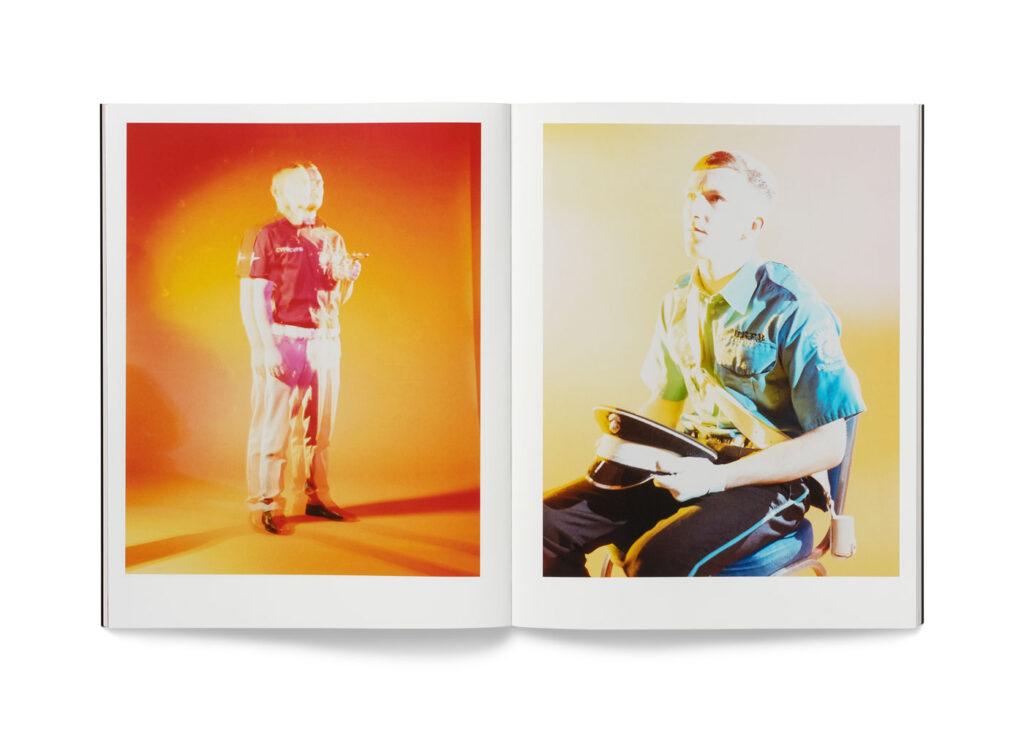

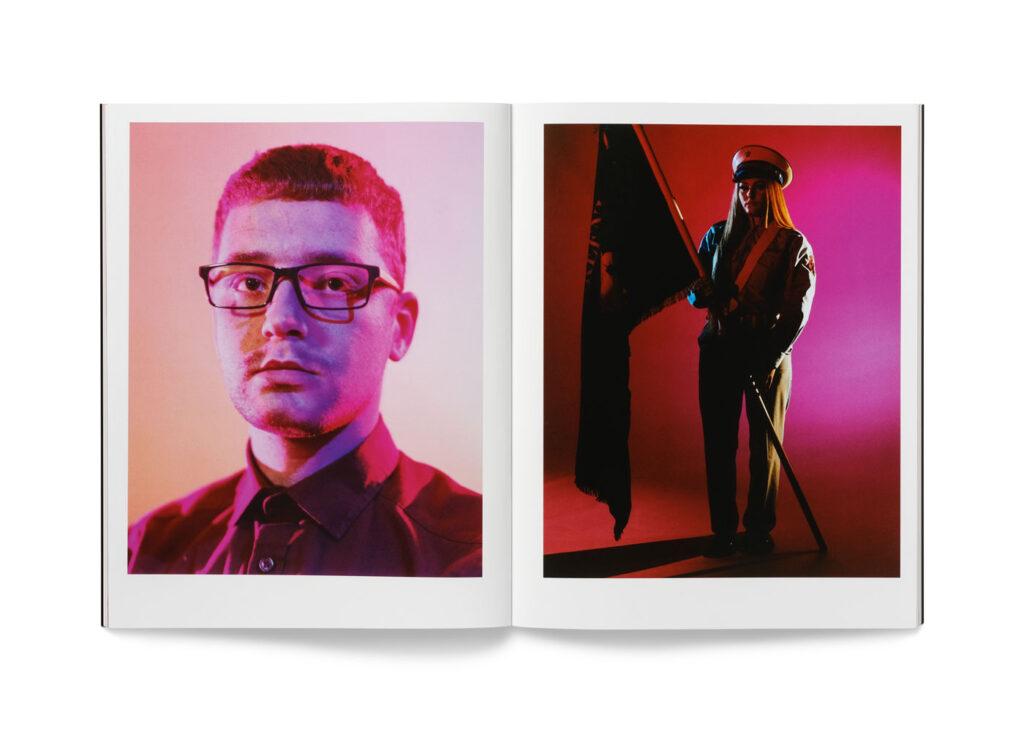

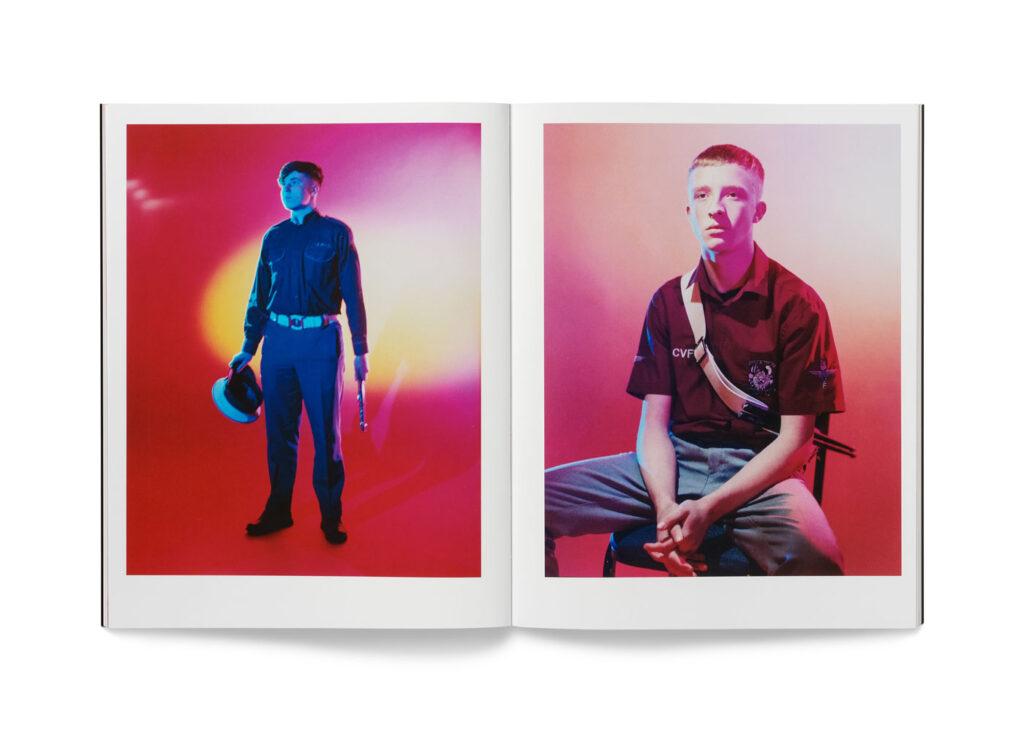

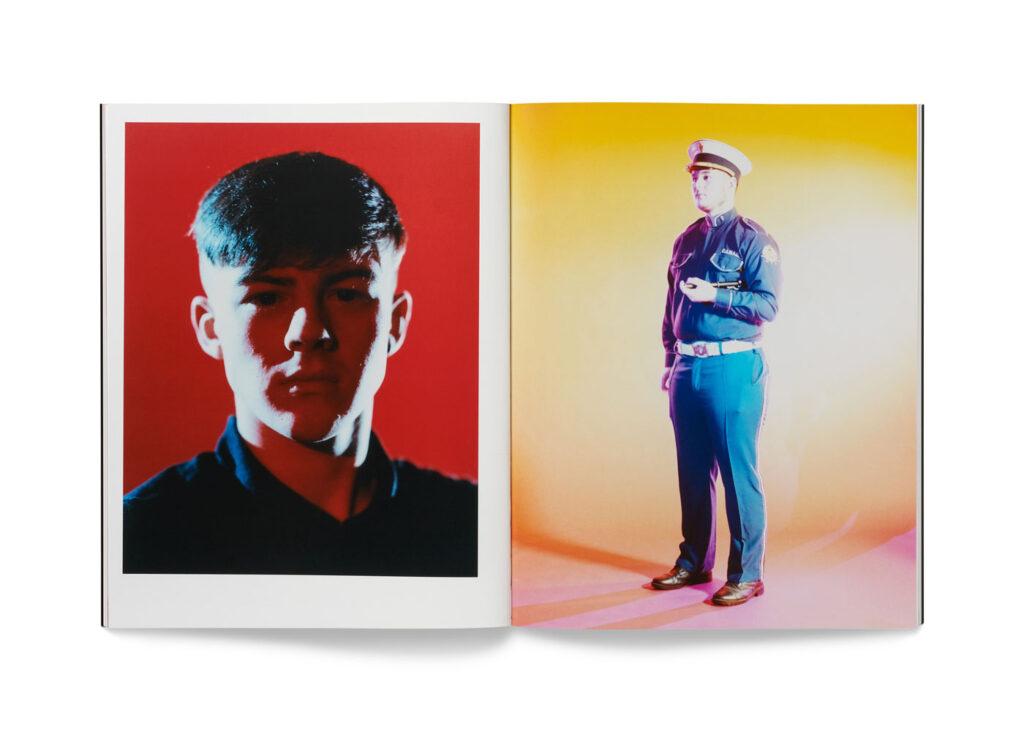

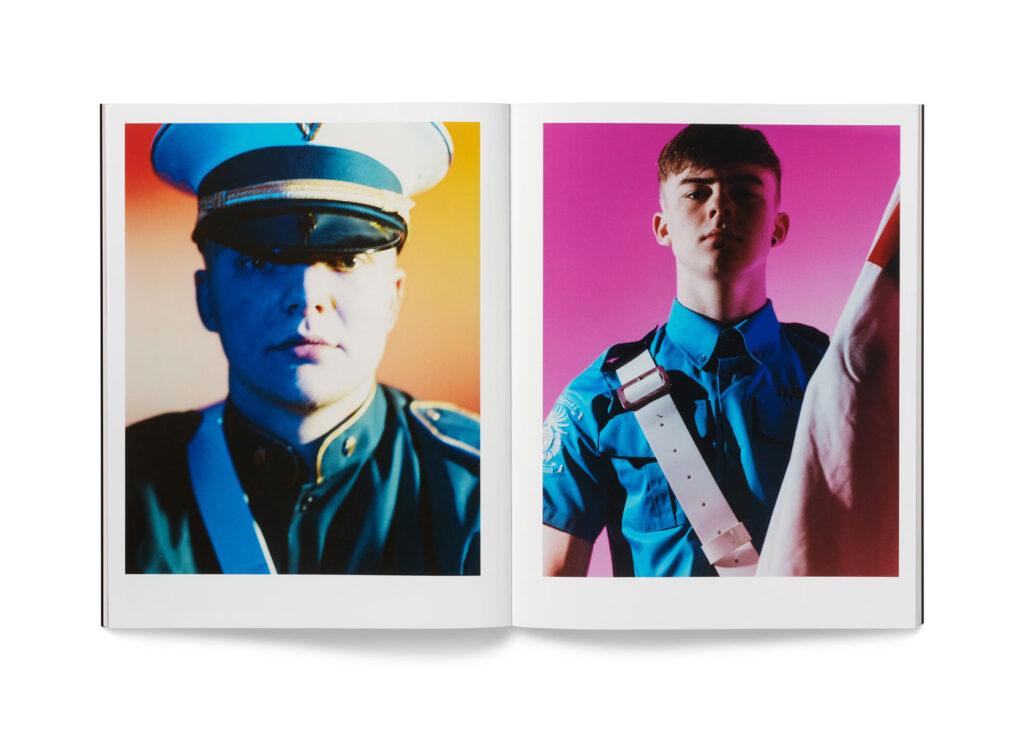

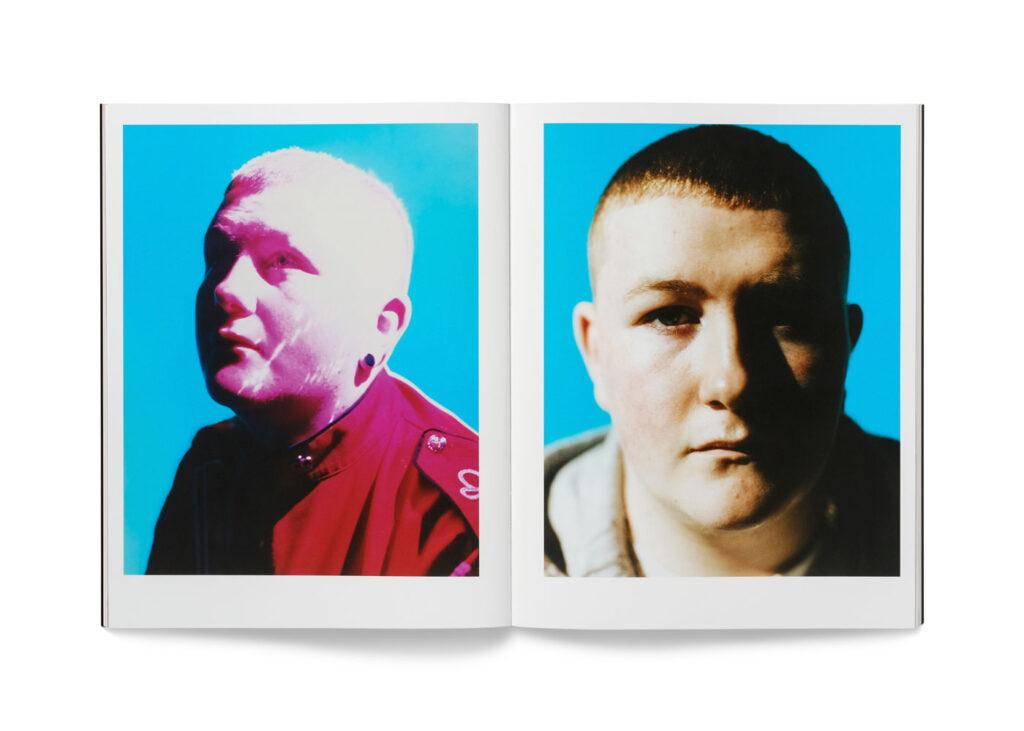

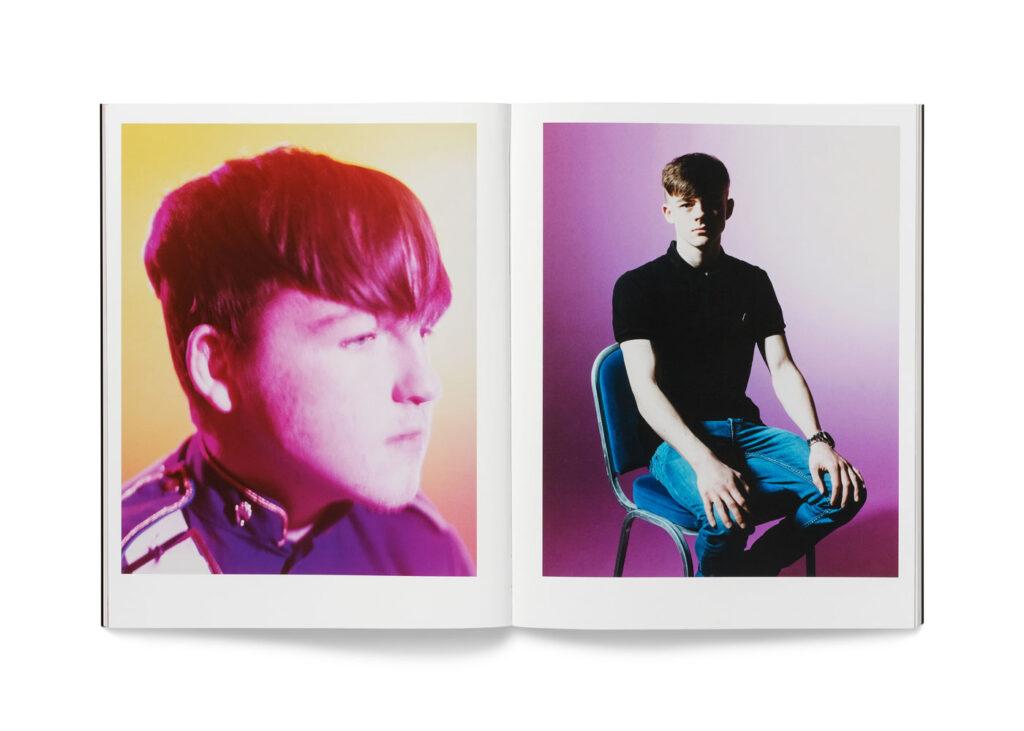

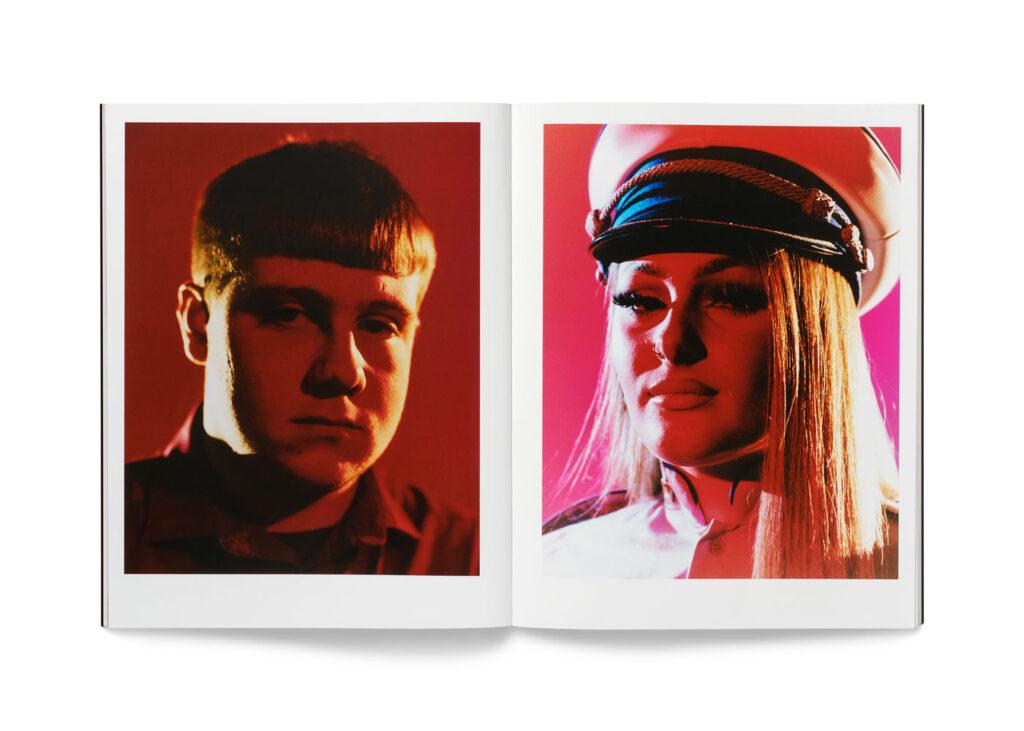

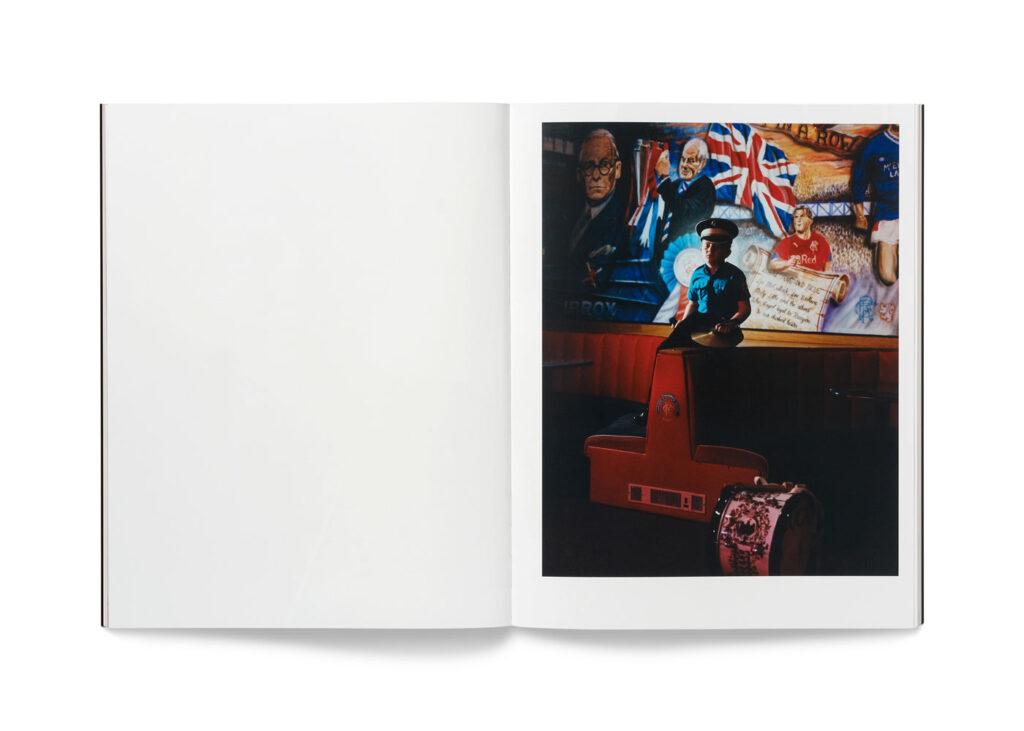

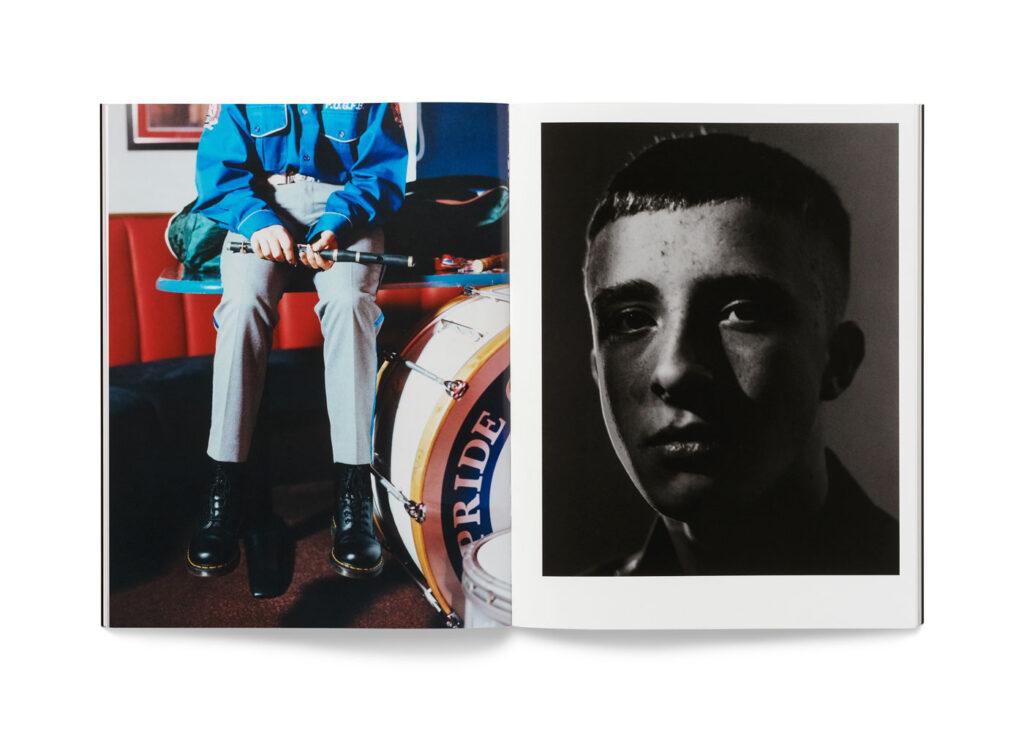

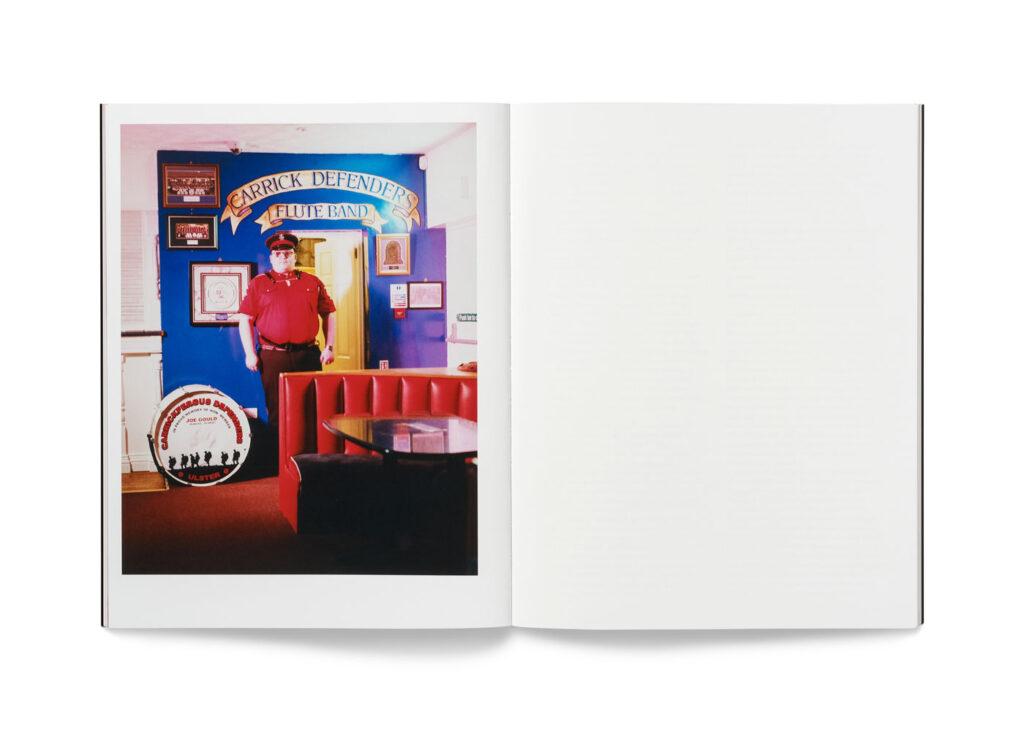

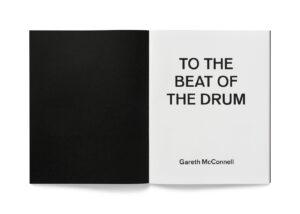

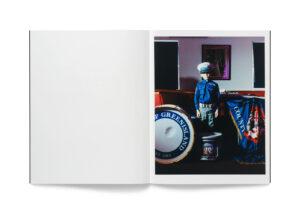

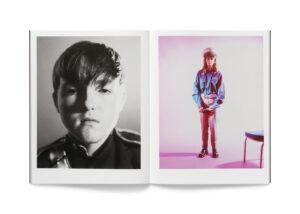

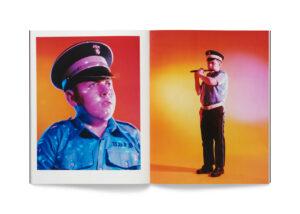

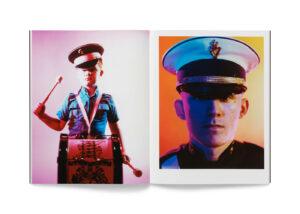

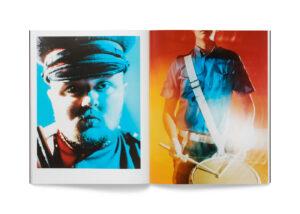

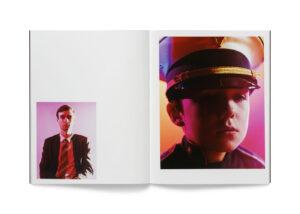

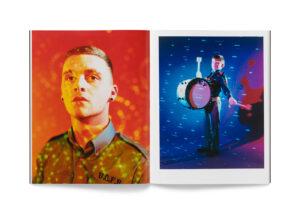

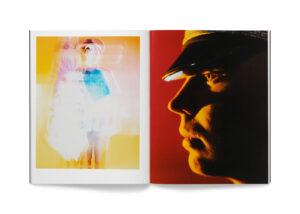

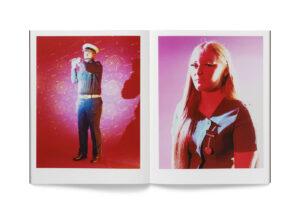

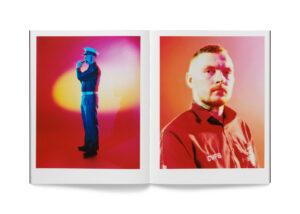

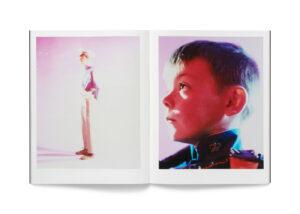

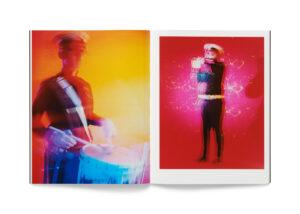

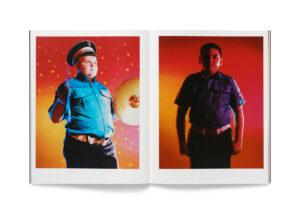

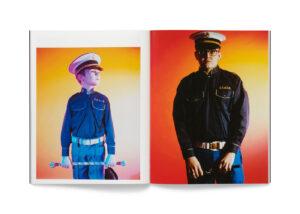

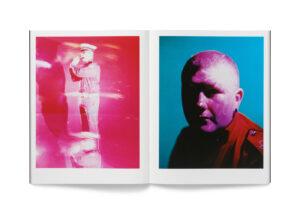

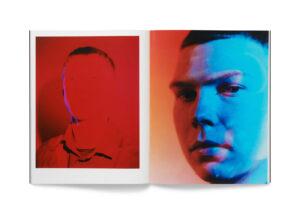

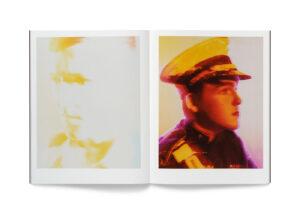

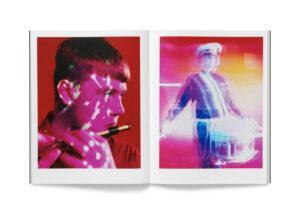

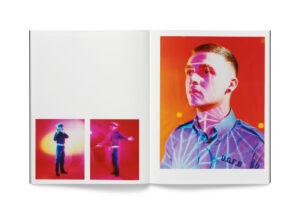

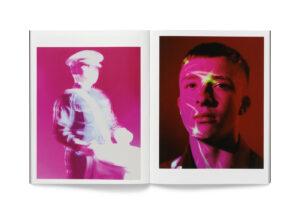

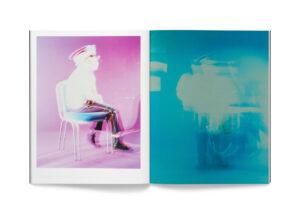

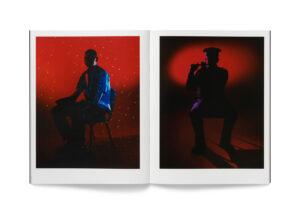

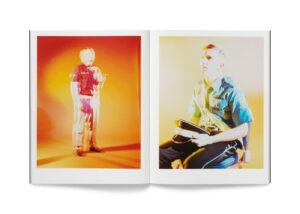

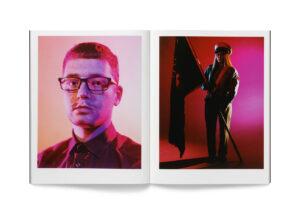

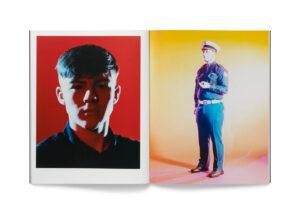

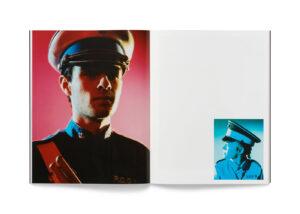

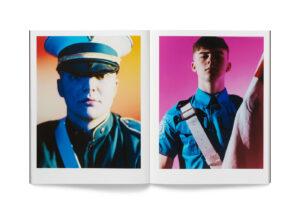

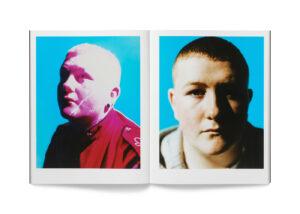

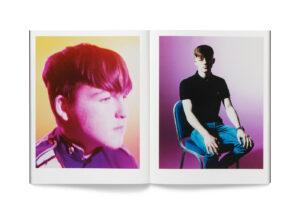

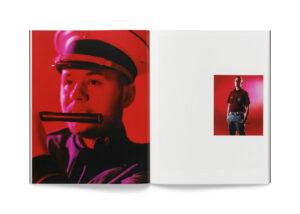

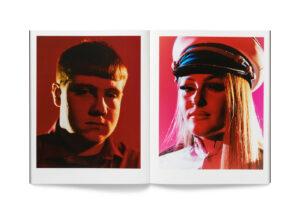

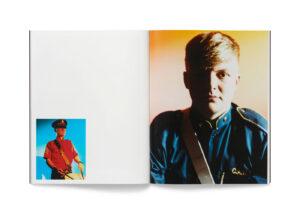

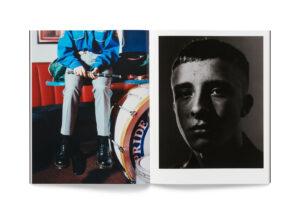

The resulting series, To the Beat of the Drum, bears his unmistakable imprint: vivid colours, atmospheric lighting and the creative use of blur and movement. Eschewing digital post-production techniques, McConnell achieves his heightened images when shooting, through the deft manipulation of light, movement and long exposures. The series, which also includes a mesmerising video piece of a young boy beating a drum, was exhibited at the Ulster Museum in Belfast in 2021. The images have no names or captions as “these strategies would ground the work in a manner more focused on the individual,” says McConnell, “while conceptually it is more about exploring or suggesting a collective experience”.

Jonathan Hodge, a local arts organiser, who commissioned McConnell on behalf of Intercomm, says of the work: “Most photographic depictions of marching bands are quite cliched in their photojournalistic approach. Gareth’s portraits, on the other hand, are arresting visually. They will probably surprise some people, while also being quite respectful to a subject that is much more culturally complex than is often portrayed in the media.”

With their banners, flags and flute bands, the annual Orange marching parades, though bemusing to many people in the rest of the United Kingdom, are perhaps the defining ritual of Protestant identity in Northern Ireland. During the marching season, April through to August, more than 2,000 parades take place in towns and villages across the country, all of them featuring flute bands. The smaller local parades are part of the protracted build-up to the much bigger celebrations that take place on 12 July. This is when members of the Orange Order, a bastion of Protestant unionism, and tens of thousands of their followers, mark the victory of King William of Orange over the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

For many Catholics/nationalists, though, the marches are viewed as sectarian and triumphalist. In the 1990s, the controversial routeing of some marches through, or close to, nationalist areas led to violent standoffs between loyalists and the police. In recent years, though, it is the often threateningly sectarian nature of the bonfire celebrations that occur on the night of 11 July in working-class loyalist areas that have caused concern and condemnation.

The 2021 marching season took place against a backdrop of simmering Unionist anger at the betrayal of the so-called “border in the Irish sea” that was created by the post-Brexit Northern Irish customs protocol. In early April, just a week after McConnell shot these portraits, the worst rioting in years erupted in Carrickfergus and Larne, as well as in other working-class loyalist areas in Belfast and Derry. The protagonists were mainly young teenagers, though many commentators suggested that the violence had been orchestrated by older members of loyalist paramilitary groups. The BBC noted that the areas affected were “among the most deprived in the country, with the lowest level of educational attainment in Europe”. That, too, is the often-overlooked social context in which these portraits were created.

Against all this, McConnell’s portraits are all the more resonant. The young band members often exude a sense of awkward vulnerability. Bathed in soft light and colour, his subjects stare inquiringly into the lens or off into the distance as if distracted by wandering thoughts. Their engagement with the camera is tentative, uncertain, as if they’re not quite sure why they have been singled out for its attention. What is also striking is just how young some of them are. You cannot help but wonder how much the band experience is another way of inculcating in them the divisive, often sectarian attitudes that are handed down through the generations.

“Most of the younger kids didn’t really say much, probably through shyness or nervousness,” says McConnell, “but they were all very cooperative. I did wonder if many of them even knew why they were in a marching band, and what that meant in the larger social context. For many of them, it’s basically about that youthful thing of just wanting to belong to something – a band and, by extension, the place they come from.”

Hodge points out that the sense of local pride that being in a band instils is a crucial reason for the exponential growth in younger bands from working-class Protestant neighbourhoods in recent years. Their priorities, he suggests, are different from those of more established traditional bands affiliated to the Orange Order. “Over the past 20 years or so,” he elaborates, “there has developed what might even be called a subculture within the bigger culture of Protestantism. Many of the younger band members see the Orange Order as old-fashioned. So, while there are bands that are still connected to Orange lodges, many more are connected to a town or an area or a housing estate.”

For young Protestants from working-class estates, being in a band, he says, “is about enjoying the outings, the camaraderie and the competition culture that has emerged in recent years. There are competitions held almost every week in the summer, with judging and prizes awarded for uniforms and musicianship. For many young people, the main reason for wanting to join a local band is to help make it the best.”

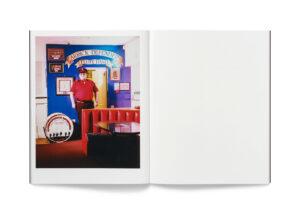

That sense of communal pride is evident too in McConnell’s portraits of young male and female band members, the embossed initials visible on their shirts often referring to local band names – the Clyde Valley Flute Band, the Pride of Greenisland Flute Band. These more straightforward portraits remind us that the subjects can’t be unmoored from their political context. The portraits also reveal the tight ties of tribal identity and conformity that hold sway in places like his staunchly Protestant home town, where one band is called the Carrickfergus Defenders. What must be defended at all costs is their Britishness, which is now perceived to be under threat not just from the Brexit customs protocol, but the possible breakup of the union if Scotland achieves independence. The shifting demographics of Northern Ireland, also suggest that an emerging generation of young people are rejecting the binary politics of belonging that have held sway for so long.

McConnell grew up in Woodburn, Carrickfergus, close to the North Road where these portraits were created in the local Rangers FC supporters’ club. Like many exiles from Northern Ireland, he experiences a complex mix of emotions when he returns there. “There’s an immediate familiarity because, to a degree, you have this shared experience and background,” he says, “plus there’s a kind of relief at being back among people who talk a lot and swear a lot, just like you do. But, alongside that, there’s also this complex feeling of belonging and yet not belonging.”

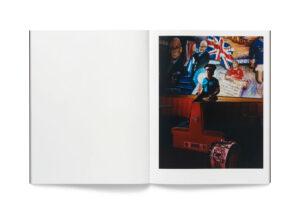

Back in 1999, while a student at the Royal College of Art, McConnell returned to Carrickfergus to make a series of photographs that explored belonging and identity in a more traditional documentary style. Portraits & Interiors from the Albert Bar is a quietly attentive, almost meditative, work that is nevertheless loaded with signifiers: paramilitary tattoos; a marching band’s drum nestling next to a beer keg; the initials UDA (Ulster Defence Association) traced in the dust on a hanging lampshade. “I was just finding my feet back then,” he says, but the photographs were critically acclaimed at the time for their assuredness.

In the interim two decades, his style has shifted dramatically, the early embrace of observational documentary giving way to a more experimental approach that blurs the boundary between the real and the imaginative. He also runs a collaborative art project and publishing imprint, Sorika, “with no particular manifesto other than the realising of projects of interest”. Intriguingly, his way of seeing, he tells me, has been determined to a degree by two very different communal experiences. As a young teenager, he remembers going to the Woodburn playing fields near to his home, where the local 12 July celebrations culminated in huge gatherings of marchers and revellers. “If you grow up in a Protestant community anywhere in Northern Ireland, the 12th is a formative experience,” he explains. “For me, as a young teenager buoyed by alcohol, it was like entering a strange and paradoxical parallel universe. On the one hand, you had very strait-laced, good-living, God-fearing Orange brethren and, on the other, there was this atmosphere of wildly exuberant mayhem fuelled by an overload of alcohol, flags, flutes and drums.”

Some years later, immersing himself in what he calls “the free-for-all autonomous zones of rave culture”, McConnell experienced a similar feeling. That the two experiences were underpinned by almost diametrically opposed world views, the one rigidly exclusive, the other utopian in its inclusiveness, is, he says, almost beside the point. It was the intensity of feeling that he experienced at each communal gathering that has stayed with him. “To some degree,” he says, “all my work has been defined by those two very different, but somehow similar and connected experiences.”

In To the Beat of the Drum, McConnell’s heightened gaze is combined with a deep understanding of, and even affinity with, his subjects and the Protestant working-class culture that defines them. As an exile, he is from, but not of, that culture. “You can leave the place you grew up in,” he says, “but of course you never really leave it behind.”